6 Ethiopian Independence in the Imperial Age

Kristen Grosserhode

Introduction: Teaching Through Rather Than About

Ethiopia remained an independent nation while its neighbors fell to European domination during the wave of New Imperialism that stretched from 1884 to 1914, when Europe was conducting its “Scramble for Africa”. It is common to view these events from a European perspective. Certainly there are myriad sources available. But the goal here is not to view imperialism in Africa through a European lens, but to view European imperialism through an African (in this case Ethiopian) lens. Ethiopian voices should be used to tell the Ethiopian story. It is their land after all. Changing this perspective may give us a very different understanding of history. Ethiopia is treated as an exception, always showing up as a different color on historical maps because it didn’t “belong” to anyone like Egypt or Ghana or Algeria. Why, though? How did Ethiopia maintain its independence when no other nation did? Often because of its exceptionalism, Ethiopia’s story is skipped over. It may appear again during WWII when Mussolini invades and wins a fleeting victory. However, in the teaching of history that tends to focus on the European journey, this exceptional case should make us pause and look closer, with excitement, to this Eastern African nation that stood against European imperialism.

In order to examine this history with authenticity and integrity, Ethiopia’s history should be told with Ethiopian voices. We should learn Ethiopian history through Ethiopian primary sources rather than learn about Ethiopian history through Western sources. It is easy to find a Puck cover that clearly and cleverly shares the European view of Africa, but what did Ethiopians have to say during the same time period about the same events? In any telling of history, the voices chosen show us who has the power, whose rendition gets shared, who gets to direct the narrative. Teachers and students should pay close attention to this! It is easy to default to the sources most readily available–likely in English and from an American or European perspective. However, digging a little deeper to teach through Black voices, through Black histories, instead of about them, will be worth the effort.

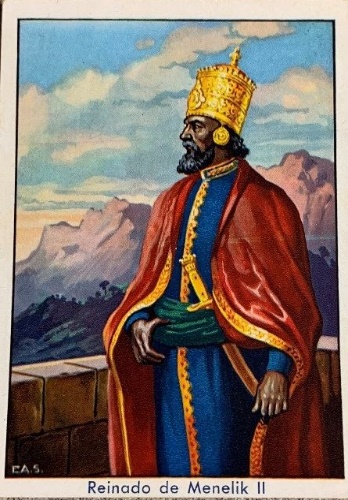

Many of the key sources in this lesson come from King Menelik II, a powerful and revered figure in Ethiopian history for his role in leading Ethiopia to defeat Italy in the Battle of Adwa and show the world that Africa was not just up for the taking. To teach through Black histories, this lesson looks at history through Menelik’s voice as he navigated this turbulent time. Another fascinating source is the Kebra Nagast, a religious and historical work that describes Ethiopia’s proud place in Christian history. Of course one may read in the Bible about Ethiopia, but the Kebra Nagast shows us what Ethiopia has to say about its own Biblical role. Many written sources were produced in Amharic, so the English translations are provided. It is possible to find images of the Treaty of Wuchale in Amharic as well as the Amharic recording of Menelik to Queen Victoria, but again, English translations are provided here.

Framework

This lesson fits into a Black Historical Consciousness framework by demonstrating the qualities of Black Agency, Resistance and Perseverance as well as Black Historical Contention. To give honor and power to the stories of Black people, the sources used will be from the voices of Black people. As mentioned above, Ethiopia was an exceptional nation during this time period. Not falling to European power shows Ethiopian agency, resistance and perseverance. When none of its neighbors could claim the same, Ethiopia shows us that not all African nations were doomed to the same colonial fate. In fact, Liberia also escaped European control. This demonstrates historical contention by acknowledging that we cannot make a blanket statement about Africa being colonized. There was another story happening on the continent with a very different ending. Too often, this story is ignored.

Pedagogical Applications

When considering pedagogical strategies and applications, this lesson clearly focuses on analyzing primary sources, comparing and contrasting, and drawing conclusions. In terms of Costa’s Levels of Questioning, all levels will be used. The approach employed here gradually takes students from identifying to comparing to defending using primary sources and group support. The bulk of the sources used are from Ethiopia, which is likely unusual for most American students–but the goal is to teach through Black histories!

Students will use writing and speaking to organize and share ideas throughout the lesson. A quick write will get ideas flowing; analyzing maps and identifying natural resources will help students visualize Ethiopia geographically; comparing and contrasting Ethiopian and European sources will guide students to consider different historical perspectives; and analyzing Ethiopian political and military primary sources will facilitate students’ viewing of European imperialism through Ethiopian eyes while demonstrating Ethiopia’s incredible ability to fend off foreign domination.

Connections to Oregon State Social Science Standards:

- HS.41: Use maps, satellite images, photographs, and other representations to explain relationships between the locations of places and regions and their political, cultural, and economic dynamics.

- HS.62: Identify historical and current events, issues, and problems when national and/or global interests are/have been in conflict, and provide analysis from multiple perspectives.

- HS.68: Select and analyze historical information, including contradictory evidence, from a variety of primary and secondary sources to support or reject a claim.

- HS.69: Create and defend a historical argument utilizing primary and secondary sources as evidence.

| Essential Question |

How did Ethiopia manage to remain independent during the second wave of European imperialism (1884-1914)? |

|---|---|

| Standards | HS.41: Use maps, satellite images, photographs, and other representations to explain relationships between the locations of places and regions and their political, cultural, and economic dynamics.

HS.62: Identify historical and current events, issues, and problems when national and/or global interests are/have been in conflict, and provide analysis from multiple perspectives. HS.68: Select and analyze historical information, including contradictory evidence, from a variety of primary and secondary sources to support or reject a claim. HS.69: Create and defend a historical argument utilizing primary and secondary sources as evidence. |

| Staging |

Quick write: What does it mean to be victorious? A winner? How do you know when you are victorious or when you have won? What do you do with your status as victor? |

| Supporting Question 1 |

Did Ethiopia have resources attractive to Europeans? |

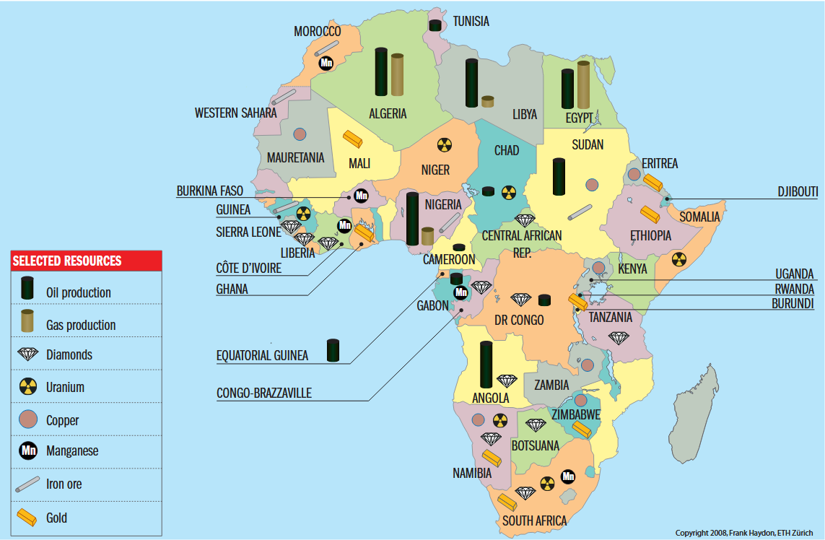

| Formative Performance Task | Novel Ideas Only brainstorm: Africa’s natural resources |

| Featured Sources | South African History Online Natural Resources map and lesson

African natural resources map |

| Supporting Question 2 |

Did Ethiopia’s culture identify closely enough with Europe that “civilizing” was not needed? |

| Formative Performance Task | T-chart comparison of European and Ethiopian culture |

| Featured Sources | King Menelik’s call to arms

King Menelik’s declaration of blackness Kebra Nagast Charles Leandre Menelik cartoon Edmund Burke quote Spanish painting of Menelik |

| Supporting Question 3 |

Did Ethiopia have a superior political and military situation from 1884-1914? |

| Formative Performance Task | Jigsaw of Ethiopian political and military sources |

| Featured Sources | King Menelik’s letter to Sudan

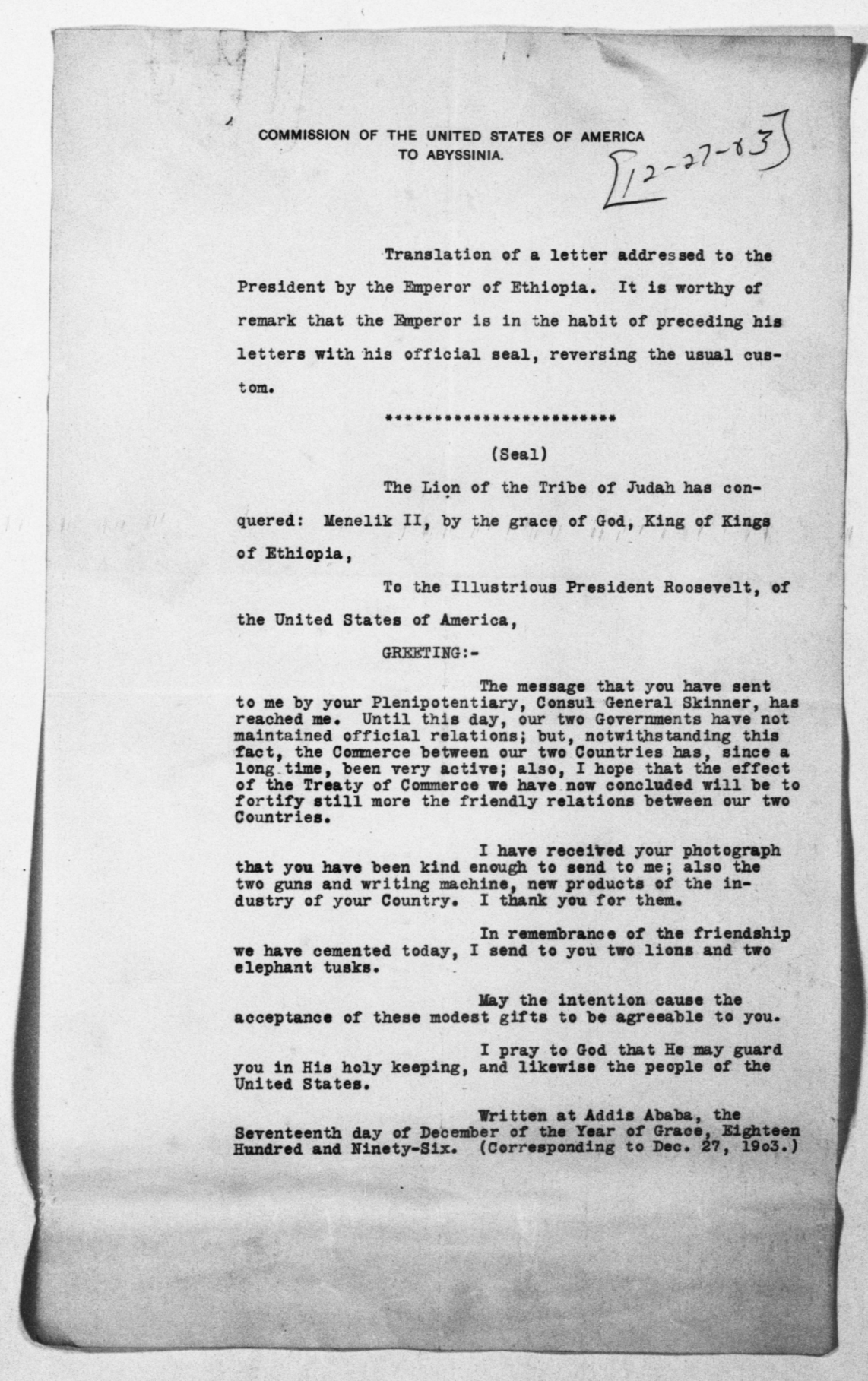

King Menelik’s recording to Queen Victoria King Menelik’s letter to European nations regarding Ethiopia’s borders King Menelik’s letter to President Roosevelt Treaty of Wuchale Battle of Adwa painting |

| Summative Performance Task |

CEA paragraph responding to the essential question with three pieces of evidence OR Propaganda poster illustrating a response to the essential question with three pieces of evidence. |

| Potential Civic Engagement |

This lesson allows students to examine and consider different government and leadership types. Ethiopia was a monarchy at the time. If students have not already learned about types of government, take time to teach them about democracy, theocracy, aristocracy, plutocracy, oligarchy, communism, autocracy, and monarchy. Ask students to consider if one type of government is more suited to certain situations–historical or contemporary. |

Lesson Narrative

In 1884, European nations met at the Berlin Conference to divide Africa amongst themselves, deciding who would colonize which areas and have access to the resources found there. They agreed to policies to make this scramble as amicable as possible. Of course, as the South African History Online site explains, this was done without the consent of any African people and resulted in decades of African exploitation.

However, Ethiopia managed to remain independent. If one nation could, why not all? This lesson is an inquiry-based lesson to explore what made Ethiopia different from the other nations. The time period of interest is 1884-1913, during the so-called “Scramble for Africa”, instigated by Belgium’s interest in the Congo. African nations suffered terribly during this time and continue to feel the effects today. In the case of Belgium, the king has expressed regrets and some officials have apologized for the cruelty of their colonization. Ethiopia escaped this fate. A natural extension of this lesson would be to examine Ethiopia’s current economic and political situation and compare it with a nation like the Democratic Republic of the Congo to look for long-term effects of such colonization. This lesson remains historical. There are general information sources and some European sources used to aid in providing context. Because he was a prolific political figure and many sources are available, the primary subject is King Menelik II, the leader of Ethiopia during the era of study. Students will be drawing their own conclusions to answer the essential question in written or illustrated form using the sources, activities, and discussion provided. The activities include a quick write, analyzing maps to answer Question 1, comparing and contrasting sources in a T-chart to answer Question 2, and analyzing sources in a Jigsaw to answer Question 3. All activities beyond the quick write involve group work. The final product will be a CEA paragraph or propaganda poster that demonstrates each student’s conclusion to the essential question. There is no definitive answer to the essential question; it is truly up to the student to determine, using evidence, to decide.

Prior Knowledge: Students should have some prior knowledge including understanding the Industrial Revolution, the 1815 Vienna Congress and Europe’s desire to avoid international war, and the 1884 Berlin Conference. This lesson is designed to fit into a unit on imperialism, to serve as one example of many Afro-European interactions during the age of New Imperialism. Students should understand Europe’s hunger and motivations for empire, leading up to and after the Berlin Conference, before beginning this lesson. The teacher may want to give a lesson to introduce King Menelik, Queen Taytu, and Ethiopia. A useful source for creating a lesson or slides to use for the Scramble for Africa background information is the South African History Online lesson website. The lesson can be used for information and context, background reading for the teacher or additional reading for students. For providing a brief online biography of King Menelik II of Ethiopia. *Disclaimer: This lesson is not meant to be all-inclusive for teaching about imperialism and the European history behind it.

Overview and Description of the Essential Question

The essential question is: How did Ethiopia manage to remain independent during the second wave of European imperialism (1884-1914)? It is the hope of this lesson that students will see how a strong leader like Menelik II was able to navigate the European Scramble for Africa on his own terms, uniting his people and contending with Europe on equal political and military footing. Through predominantly Ethiopian primary sources, students will use inquiry to develop their own understanding and form a response to the question. Depending on the length of classes, this lesson may take 1-2 days to complete. In order to give sufficient time for quality summative assessments, two days is a better commitment.

- Staging the Question (10 minutes)

- Question 1 (15 minutes)

- Question 2 (20 minutes)

- Question 3 (15-20 minutes)

- Summative Task (30-60 minutes, perhaps done as homework or on a separate day)

PowerPoint slides to teach this lesson: Ethiopian Independence (pptx)

Staging the Question

Begin the lesson with a quick write addressing these questions: What does it mean to be victorious? A winner? How do you know when you are victorious or when you have won? What do you do with your status as victor? When you hear the word “winner” who is a person or entity you think of? Do you admire them? Why?

Ask students to write for five minutes and then cold call or take volunteers to share out and lead an organic discussion. Perhaps write down their big ideas on the board where you can return to them later.

The idea is that most studies of this time period focus on Europe’s domination of the African kingdoms. This lesson, though, focuses on Ethiopia’s resistance to domination. By the end of the lesson, this question should be brought up again by asking if Ethiopia was victorious in a way that was meaningful to them. Students might think of winners in sports or elections, but not necessarily nations. So, how does a nation “win”, specifically in an imperial setting? What does an admirable victory look like in this context? What should the winning nation do with its power?

Question 1, Formative Task 1, Featured Sources

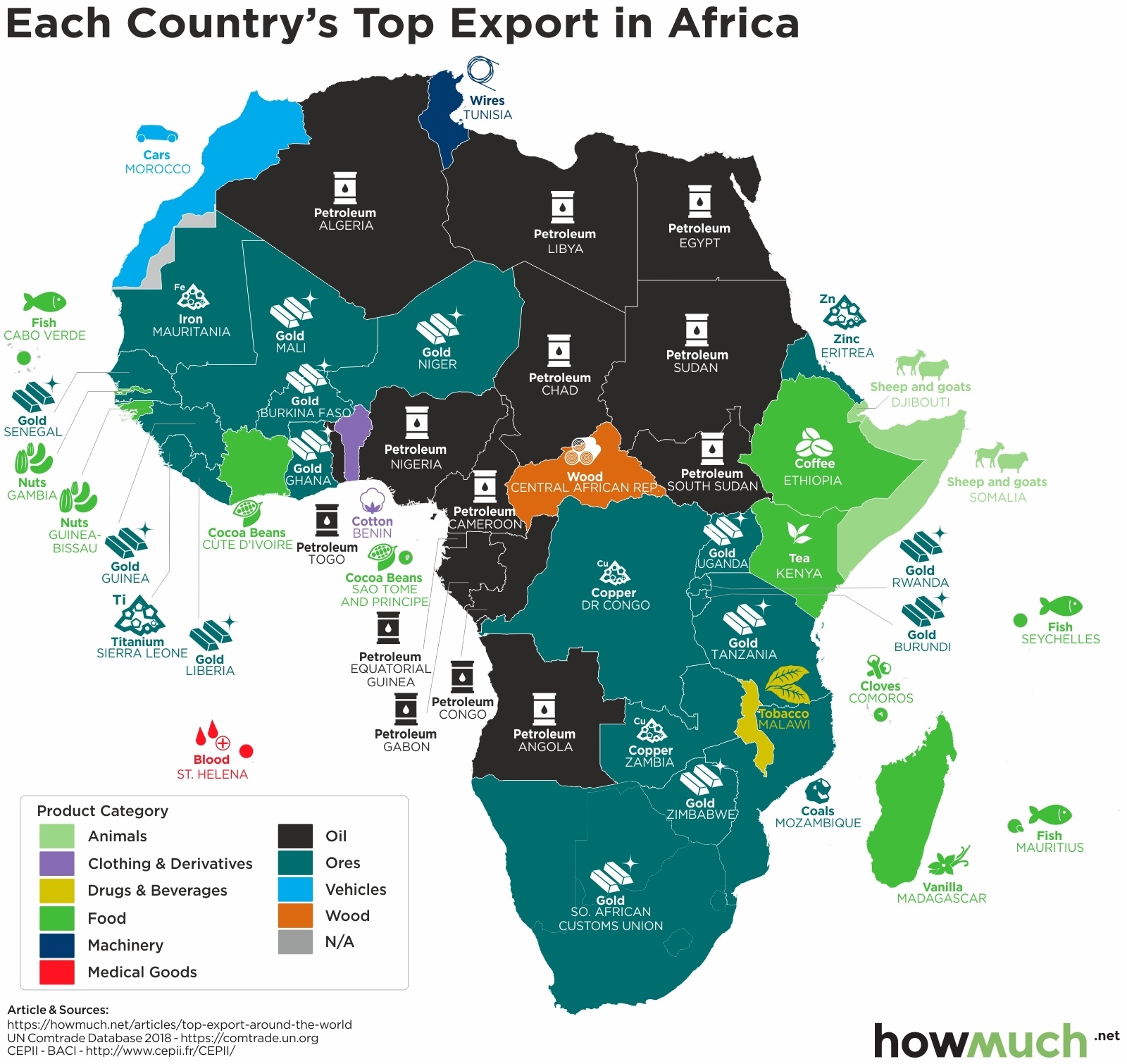

Question: Did Ethiopia have natural resources attractive to Europeans?

Sources: South African History Online lesson and resource map (see map below). The lesson can be used for information and context, background reading for the teacher or additional reading for students. The map is the essential source for the activity.

Activity: Novel Ideas Only. Students will be in groups of 3-4. Equip each group with a small whiteboard and dry erase markers or simply a piece of paper and pen. Students should be familiar with the concept of imperialism and colonization and be familiar with the Scramble for Africa (at least that European nations began quickly and greedily carving out African colonies for themselves in the late 1800s). Ask students to make a list of valuable natural resources in Africa. What kinds of resources would make European nations so eager to gain colonies? Allow 2 minutes. Ask the first group to read their list. The teacher or a volunteer student should record a master list at the front of the class. All other groups must cross off any ideas on their own list that are stated by the first group. The second group will read what remains on their list. All other groups must cross off any ideas repeated in their own list. Continue to the last group (they may or may not have anything left on their list). Correct answers should include: gold, diamonds, oil, rubber, timber, gas, coal, copper, uranium, cobalt, coffee, tropical fruits, platinum.

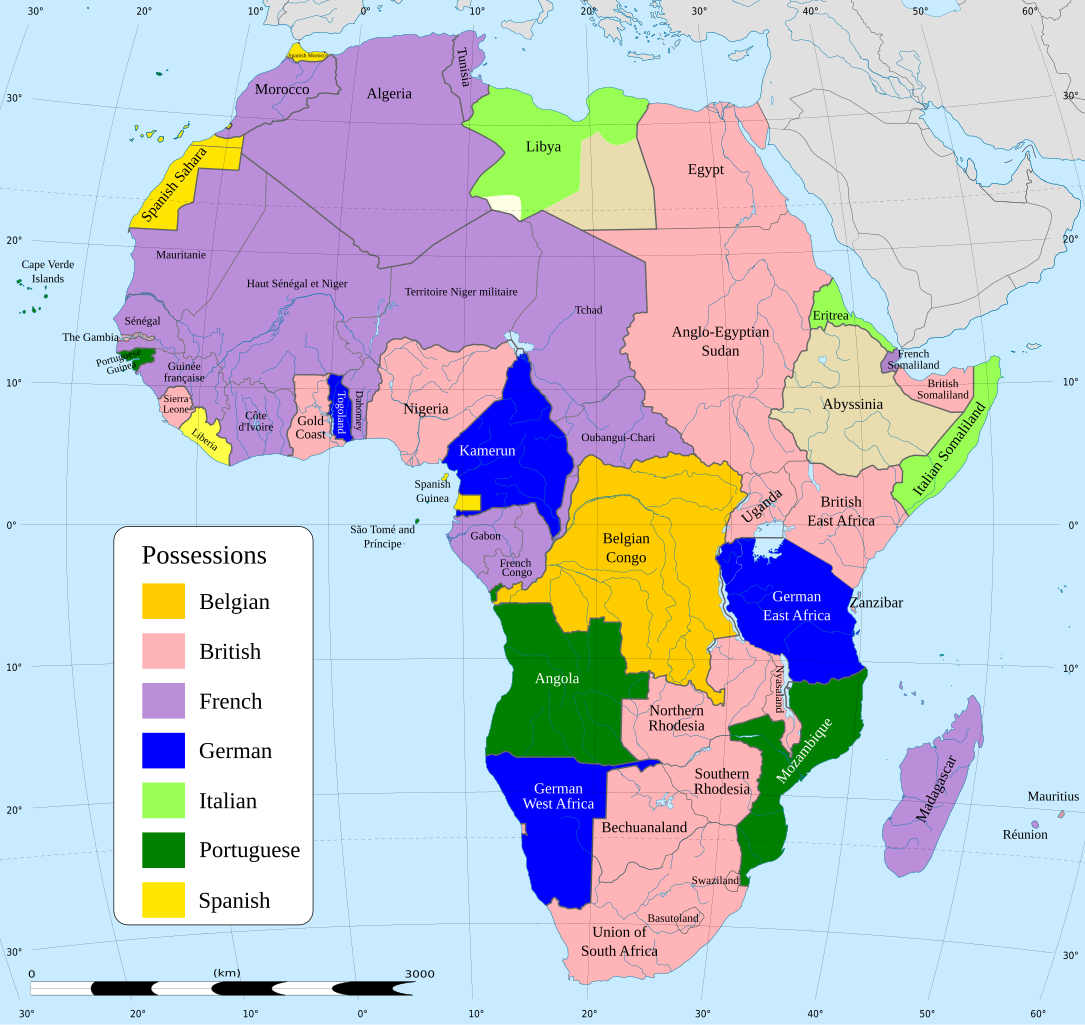

Now introduce the fact that Ethiopia was never colonized by Europe. Use this map image to show colonization of Africa. There are many renditions of this map online, so you can also choose one you like. Ask students to find Ethiopia and make observations. How is it different from the other parts of Africa? Correct answers should include that it is independent or not controlled by a European empire.

Ask students if Ethiopia perhaps didn’t have any of the valuable natural resources they listed earlier–could that be a reason Ethiopia remained independent? Select 1-2 students to give their answer.

Show the following maps (Figures 6.2 and 6.3) and ask students to take 1-2 minutes to quietly study them. Ask them to discuss and agree as a group whether Ethiopia had valuable resources. Ask for a student volunteer to share their answer with the class. Correct answer should indicate that yes, Ethiopia had valuable resources (gold, agricultural products).

Ask students if the other parts of Africa were colonized for resources, and Ethiopia had valuable resources too, what other explanation could there be for its independence? Solicit student ideas and discuss as needed before moving to the next question.

Question 2, Formative Task 2, Featured Sources

Question: Did Ethiopia’s culture identify closely enough with Europe that “civilizing” was not needed?

Ethiopian Sources:

King Menelik II’s call to arms:

“Now an enemy that intends to destroy our homeland and change our religion has come crossing our God-given frontiers digging in like a mole. Now, with the help of God, I will not allow him to have my country. You, my countrymen, I have never knowingly hurt you, nor have you hurt me. Help me, those of you with zeal and will power; those who do not have the zeal, for the sake of your wives and your religion, help me with your prayers.” (1896 declaration recorded by Battle of Adwa eyewitness, Gebre Selassie).

King Menelik II’s declaration of blackness:

“I am black, and you are black; let us unite to hunt our common enemy.” (1895 quote when trying to convince Muslims to help fight imperial Italy).

Kebra Nagast (Glory of the Kings). This is a collection of stories, history, myths, legends of Abyssinia/Ethiopia that explains how the kings of Ethiopia are descended from the son, named Menelik, of Israel’s King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, making them relatives of the divine line of Christ and closely related to the Semitic peoples of Asia. It even claims that the Ark of the Covenant was taken to Ethiopia because the Jews were not worthy to care for it. It was collected and written over the centuries in several languages due to conquest and eventually translated into Ethiopian in the Middle Ages. Use some or all of the following quotes and excerpts from the Kebra Nagast to illustrate Ethiopia’s proud Christian heritage.

The text was taken to England and in 1872, King John IV of Ethiopia wrote to ask for it back saying:

“Again there is a book called KIVERA NEGUST (i.e. KEBRA NAGAST), which contains the Law of the whole of ETHIOPIA, and the names of the SHUMS (i.e. Chiefs), Churches, and Provinces are in this book. I pray you will find out who has got this book, and send it to me, for in my Country my people will not obey my orders without it” (King John IV to Lord Granville regarding the Kebra Nagast being returned to Ethiopia).

The introduction to the Kebra Nagast states:

“IN PRAISING GOD THE FATHER, THE SUSTAINER OF THE UNIVERSE, AND HIS SON JESUS CHRIST, THROUGH WHOM EVERYTHING CAME INTO BEING, AND WITHOUT WHOM NOTHING CAME INTO BEING, AND THE HOLY TRIUNE SPIRIT, THE PARACLETE, WHO GOETH FORTH FROM THE FATHER, AND DERIVETH FROM THE SON, WE BELIEVE IN AND ADORE THE TRINITY, ONE GOD, THE FATHER, AND THE SON, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT.”

Chapter 20 states:

“From the middle of JERUSALEM, and from the north thereof to the south-east is the portion of the Emperor of RÔM; and from the middle of JERUSALEM from the north thereof to the south and to WESTERN INDIA is the portion of the Emperor of ETHIOPIA. For both of them are of the seed of SHEM, the son of NOAH, the seed of ABRAHAM, the seed of DAVID, the children of SOLOMON. For God gave the seed of SHEM glory because of the blessing of their father NOAH. The Emperor of RÔM is the son of SOLOMON, and the Emperor of ETHIOPIA is the firstborn and eldest son of SOLOMON.”

Chapter 21 states:

“And our Lord JESUS CHRIST, in condemning the Jewish people, the crucifiers, who lived at that time, spake, saying: “The Queen of the South shall rise up on the Day of Judgment and shall dispute with, and condemn, and overcome this generation who would not hearken unto p. 17 the preaching of My word, for she came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of SOLOMON.”1 And the Queen of the South of whom He spake was the Queen of ETHIOPIA.”

On one of her visits to Solomon, she devoted her life to the God of Israel.

Chapter 28 says:

“And the Queen said, “From this moment I will not worship the sun, but will worship the Creator of the sun, the God of ISRAEL. And that Tabernacle of the God of ISRAEL shall be unto me my Lady, and unto my seed after me, and unto all my kingdoms that are under my dominion. And because of this I have found favour before thee, and before the God of ISRAEL my Creator, Who hath brought me unto thee, and hath made me to hear thy voice, and hath shown me thy face, and hath made me to understand thy commandment.” Then she returned to [her] house.”

Chapter 32 explains the birth of her son, the son of Solomon, cementing Ethiopia’s connection to Israel:

“And the Queen departed and came into the country of BÂLÂ ZADÎSÂRĔYÂ nine months and five days after she had separated from King SOLOMON. And the pains of childbirth laid hold upon her, and she brought forth a man child, and she gave it to the nurse with great pride and delight. And she tarried until the days of her purification were ended, and then she came to her own country with great pomp and ceremony. And her officers who had remained there brought gifts to their mistress, and made obeisance to her, and did homage to her, and all the borders of the country rejoiced at her coming. Those who were nobles among them she arrayed in splendid apparel, and to some she gave gold and silver, and hyacinthine and purple robes; and she gave them all manner of things that could be desired. And she ordered her kingdom aright, and none disobeyed her command; for she loved wisdom and God strengthened her kingdom.”

Chapter 117 describes Ethiopia’s mission to destroy the Jews and then their divine status:

“And they were to rise up to fight, to make war upon the enemies of God, the JEWS, and to destroy them, the King of RÔMÊ ’ÊNYÂ, and the King of ETHIOPIA PINḤAS (PHINEHAS); and they were to lay waste their lands, and to build churches there, and they were to cut to pieces JEWS at the end of this Cycle in p. 226 twelve cycles of the moon. Then the kingdom of the JEWS shall be made an end of…Thus hath God made for the King of ETHIOPIA more glory, and grace, and majesty than for all the other kings of the earth because of the greatness of ZION, the Tabernacle of the Law of God, the heavenly ZION. And may God make us to perform His spiritual good pleasure, and deliver us from His wrath, and make us to share His kingdom. Amen.”

European Sources

Charles Leandre (French cartoonist) cartoon of King Menelik II after his defeat of Italy, late 1800s. Italy is the woman held in Menelik’s arms (Figure 6.4).

![French artist Charles Leandre,) painted the caricature of Menelik. Below the picture the artist wrote, “The benevolent Negus [i.e., King] takes advantage of the victory, but he never abuses it.” The underlying message is that the “beastly” and “barbarian” king is going to shame Europe (i.e., Italy), here represented by the helpless, naked woman clutched in his monster-like hands.](https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/370/2024/10/hvd.hn4kyv-seq_493-scaled.jpg)

Edmund Burke (British statesman) quote, 1777:

“Now the Great Map of Mankind is unrolled at once; and there is no state or Gradation of barbarism, and no mode of refinement which we have not at the same instant under our View. The very different Civility of Europe and of China; the barbarism of Persia and Abyssinia [Ethiopia], the erratic manners of Tartary, and of Arabia. The Savage state of North America, and of New Zealand.”

Spanish artist rendition of King Menelik after victory over Italy, 1896 (Figure 6.5).

Activity: T-chart comparison of European and Ethiopian views. Ask students what Europeans prided themselves on; what made them feel superior or like they had to go dominate other parts of the world? You might mention “gold, glory, God” or “missionaries, militaries, and mercantilism”. Correct answers should include that Europeans thought they were culturally superior (religion, language, customs), that they needed certain resources to fuel their new industrial economies, and thus needed militaries to facilitate acquisition of such resources from perceived inferior peoples.

Prepare slides or handouts of each source to share with the class. Students should still work in groups of 3-4. Provide the T-chart below to each student. Present sources one at a time. Ask students to record how Ethiopians saw themselves using Ethiopian sources and how Europeans saw Ethiopians using European sources. Allow time with each source for students to read, ask questions, discuss in groups, and make a chart entry.

If students do not have prior knowledge of European culture, it may be helpful to provide some for comparison. Some points to include would be that Europe was predominantly Christian, whether Catholic, Protestant or Orthodox. Teachers should recall the Treaty of Tordesillas, which stipulated that any lands in the Americas already ruled by a Christian king could not be colonized. Of course, there were no Christian indigenous rulers, opening the door for total colonization. Even during the Enlightenment, when traditional methods were being left behind for more reasoned and practical ones, philosophers and agents of political change still called on God or a Supreme Being to bear witness to their revolutions. The period of time during this lesson is after the Enlightenment, which means ideas of equality are already widespread as well. It is post-colonial in that colonies in the Americas have earned their freedom due to these Enlightenment principles; additionally, France has survived her revolution. This should serve to highlight that Europe values Christianity, equality, and liberty–at least on paper. Europe is still concerned with empire, though, and accumulating resources and wealth through colonies, protectorates, and spheres of influence.

Cold call or take volunteers to share what they noted: How did Ethiopians view themselves and their culture? How did Europeans view them? Correct answers should include that Ethiopians saw themselves as Christians, religiously similar to Europeans, the kings were referred to as “king of kings” indicating superiority, Ethiopians also demonstrated antisemitic attitudes common in Europe, the Ethiopian leader identified as Black and called on other Black people to unite. Europeans on the other hand saw Ethiopians (Abbyssinians) as barbaric, as disfigured, perhaps Christian but not equally so, or in a similar vein to Native Americans as “noble savages”.

Ask students to take 2-3 minutes to answer the last question on the T-chart (Table 6.2): Was there a significant difference that would have inspired Europeans to act on the 3 Gs or 3 Ms of imperialism to invade Ethiopia?

Questions:

- Did Ethiopia’s culture identify closely enough with Europe that “civilizing” was not needed?

- How did Ethiopians view themselves and their culture? How did Europeans view Ethiopians? Look at the sources provided and discuss with your group before making notes in the T-chart below.

- Was there a significant cultural difference that would have inspired Europeans to invade Ethiopia?

| Ethiopia | (insert views here) |

|---|---|

| Europe | (insert views here) |

Question 3, Formative Task 3, Featured Sources

Question 3: Did Ethiopia have a superior political and military situation from 1884-1914?

Sources:

King Menelik’s letter to the caliph of the Sudan:

This is to inform you that the Europeans who are present round the White Nile with the English have come out from both the east and the west, and intended to enter between my country and yours and to separate and divide us. And I, when I heard of their plan, dispatched an expedition, sending detachments in five directions. The group [of Europeans] who are near are the English and the French, who are located in the direction from which the Belgians came. And do you remember when I sent to you Kantiba Jiru, you wrote to me by him that you have men in the direction from which the Belgians came?; and I ordered the chiefs of [my] troops that if they met with them, they were to parley with them and explain [my] intention. And now I have ordered my troops to advance towards the White Nile. And perhaps [if] you heard the news from merchants or from others you might misunderstand my action, [so now] I have written to you so that you would understand the object [of this expedition]. And you look to yourself, and do not let the Europeans enter between us. Be strong, lest if the Europeans enter our midst a great disaster befall us and our children have no rest. And if one of the Europeans comes to you as a traveler, do your utmost to send him away in peace; and do not listen to rumors against me. All my intention is to increase my friendship with you, and that our countries may be protected from [their] enemies.

King Menelik’s recording to Queen Victoria, 1899.

Queen Victoria’s phonograph recording to King Menelik and his wife, the empress. England (and Europe in general) sought alliances with Ethiopia to check the spread of the Ottoman empire.

“I, Victoria, Queen of England, hope your Majesty is in good health. I thank you for the kind reception which you have given to my Envoys, Mr. Rodd and Mr. Harrington. I wish your Majesty and the Empress Taitou all prosperity and success, and I hope that the friendship between our two Empires will constantly increase.”

King Menelik’s response:

“I, Menelik II, king of kings of Ethiopia, say to our very honoured friend Victoria, Queen of the great English people, ‘May the Saviour of the World give you health! When the very beautiful and excellent phonograph (recording) of the Queen reached me by the hands of Monsieur Harrington and when I heard the voice of Your Majesty (as if) you were beside me, I listened with great pleasure. May God thank you for your good wishes for us and for my kingdom. May God give you long life and health and give your people peace and repose. I have spoken with M. Harrington concerning all issues between both our peoples. When he told me that he was now returning to England, I said to him that I would be pleased if he could settle all our affairs before coming back. And now, may the Queen receive him well. Furthermore, we have told M. Harrington about Matamma, how our great king is and many of our compatriots died there for their religious zeal. I have hopes that you will help us in having the English government recognize this city for us.May God help us that Ethiopia and England may remain in peace and friendship. Having said this, I extend my greetings of respect to your great people.”

Queen Taytu’s response:

“I, Itege (Queen) Taitu, Light of Ethiopia, say to the very honoured Queen Victoria, the great Queen of the English… May God give you health. Your phonograph has reached me. With great pleasure I listened to you (as if) you were beside me. And now, since God has willed to bring my voice to the ear of the honoured Queen, I declare … that God give you health and long life. May God keep you many years in good health.”

King Menelik’s letter to European heads of state explaining Ethiopia’s borders, written to Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia, 1891:

Being desirous to make known to our friends the Powers (Sovereigns) of Europe the boundaries of Ethiopia, we have addressed also to you (your Majesty) the present letter.

These are the boundaries of Ethiopia:-Starting from the Italian boundary of Arafale, which is situated on the sea, the line goes westward over the plain (Meda) of Gegra towards Mahio, Halai, Digsa, and Gura up to Adibaro. From Adibaro to the junction of the Rivers Mareb and Arated.

From this point the line runs southward to the junction of the Atbara and Setit Rivers, where is situated the town known as Tomat.

From Tomat the frontier embraces the Province of Gederef up to Karkoj on the Blue Nile. From Karkoj the line passes to the junction of the Sobat River with the White Nile. From thence the frontier follows the River Sobat including the country of Arbore, Gallas and reaches Samburu.

Towards the east are included within the frontier the country of the Borana Gallas and Arussi country up to the limits of the Somalis, including also the Province of Ogaden.

To the northward the line of the frontier includes the Habar Awal, the Gadabursi, and Essa Somalis , and reaches Ambos.

Leaving Ambos the line includes Lake Assal, the province of our ancient vassal Mohamed Anfari, skirts the coast of the sea, and rejoins Arafale. While tracing today the actual boundaries of my Empire, I shall endeavour, if God gives me life and strength, to re-establish the ancient frontiers (tributaries) of Ethiopia up to Khartoum, and as Lake Nyanza with all the Gallas.

Ethiopia has been for fourteen centuries a Christian island in a sea of pagans. If powers at a distance come forward to partition Africa between them, I do not intend to be an indifferent spectator.

As the Almighty has protected Ethiopia up to this day, I have confidence He will continue to protect her, and increase her borders in the future . I am certain He will not suffer her to be divided among other Powers.

Formerly the boundary of Ethiopia was the sea. Having lacked strength sufficient, and having received no help from Christian Powers, our frontier on the sea coast fell into the power of the Muslim-man.

At present we do not intend to regain our sea frontier by force, but we trust that the Christian Power, guided by our Saviour, will restore to us our sea-coast line, at any rate, certain points on the coast.

Written at Addis Ababa, the 14 th Mazir, 1883 (10th April, 1891).

Treaty of Wuchale, 1889. This treaty was signed with Italy. Italy used different language in the Amharic version and the Italian version to trick the Ethiopians into a protectorate status. When King Menelik discovered this, he abandoned the treaty and went to war with Italy, coming out victorious after the Battle of Adwa.

Article 17 in Amharic states: “his Majesty the King of Kings of Ethiopia can use the Government of His Majesty the King of Italy for all treatments that did business with other powers or governments.”

Article 17 in Italian states: “his Majesty the King of Kings of Ethiopia must use the Government of His Majesty the King of Italy for all treatments that did business with other powers or governments.”

Battle of Adwa, by unknown Ethiopian artist, showing Ethiopia’s victory over Italy, 1896 (Figure 6.6). It is important to note that Menelik was unique and revered for his ability to unite Ethiopians that resulted in a victory over Italy (refer back to his call to arms in Question 2).

Activity: Jigsaw. Keeping students in groups of 3-4, provide each student with ONE of the above sources. Allow sufficient time for students to read or examine their source while considering the questions: Did Ethiopia have a superior political and military situation from 1884-1914? How did their situation contend with Europe? How did Ethiopia interact with other African nations? Students should record their ideas on the document shown in Table 6.3.

Once students have examined their own sources, ask them to share one at a time their responses with the rest of their group. As group mates share, students should record their own response to the rest of the sources based on their group mates’ faithful reporting. If any sources are missing, discuss as a class.

Return to the quick write from the beginning of class and ask some follow up questions.

Was Ethiopia victorious in its pursuits? Was Europe victorious (specifically Italy in the case of Ethiopia)? What did “victory” mean to each contender?

With Menelik’s ability to unite the Ethiopians and defeat the Italians, does he have further obligation to Ethiopia or other African nations under European control?

Ethiopia’s Political and Military Position

Examine your assigned source while considering the following questions:

- Did Ethiopia have a superior political and military situation from 1884-1914?

- How did their situation contend with Europe?

- How did Ethiopia interact with other African nations?

Record your answer/reflection in the space that corresponds with your source.

When prompted, listen to your group mates and record a response for the remaining sources.

|

Source |

Response |

|---|---|

|

Letter to Sudan |

(insert response here) |

|

Recording to Queen Victoria |

(insert response here) |

|

Letter to Europe |

(insert response here) |

|

Treaty of Wuchale |

(insert response here) |

|

Battle of Adwa painting |

(insert response here) |

|

Letter to President Roosevelt |

(insert response here) |

Summative Performance Task

To demonstrate their understanding of the essential question, students will choose from two options: a CEA paragraph or a propaganda poster. It should be clear that the evidence used came from the sources provided in the lesson.

CEA paragraph: Write a paragraph that begins with a CLAIM to respond to the essential question. Support your claim with three pieces of EVIDENCE before providing an ANALYSIS of the evidence. This paragraph should be at least 5-8 sentences long.

Propaganda poster: Create a thoughtful and colorful poster that illustrates a response to the essential question using three pieces of evidence. This poster should be from an Ethiopian perspective, celebrating how they were able to maintain independence from European domination.

Potential Civic Engagement

This lesson allows students to examine and consider different government and leadership types. Ethiopia was a monarchy at the time, as were many of the oncoming European nations. If students have not already learned about types of government, take time to teach them about democracy, theocracy, aristocracy, plutocracy, oligarchy, communism, autocracy, and monarchy. Ask students to consider if one type of government is more suited to certain situations–historical or contemporary.

Conclusion

The essential question was: How did Ethiopia manage to remain independent during the second wave of European imperialism (1884-1914)? You may extend this lesson by asking students to find one additional source not used in the lesson (for example, King Menelik II and the Pope corresponded, or the Treaty of Addis Ababa). The goal of the lesson is not to provide students with a concrete, definitive answer. It is to provide them with sources to analyze and draw their own conclusions–thus, there may be many answers. The important part is that students explore this period of history so commonly presented through European sources instead through Ethiopian sources and develop their own answer to the essential question. Rather than continue to focus on European domination, turn the narrative on its head and present an African domination. This lesson should give students a chance to see Black history through Black eyes and show Black agency, resistance and perseverance as well as historical contention with the common narrative. Students should feel empowered to consider multiple perspectives and to look outside of their familiar narrative to examine history.

Image Attributions

[Imagination of a Spanish artist of the triumphant emperor, Menelik II]. (1896). Library of Congress African and Middle Eastern Division, Ethiopian Collection of Trade Cards. https://blogs.loc.gov/international-collections/2020/03/emperor-menelik-ii-of-ethiopia-and-the-battle-of-adwa-a-pictorial-history/?loclr=fbint

[Map of Africa in 1914, depicting European colonial possessions]. (2023). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Africa_map_1914.svg

[Untitled oil painting depicting the battle of Adwa, March 2, 1896]. (1940-1949). The Trustees of the British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/72427001. (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Central Intelligence Agency. (2024). Ethiopia. In The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ethiopia/map/

Emperor Menelik II (n.d.). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emperor_Menelik_II.png

Emperor of Ethiopia Menelik II Negusä Nägäst. (n.d.). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Negusa_Nagast_Menelik_II_Emperor_of_Ethiopia.jpg

Empress Taitu (n.d.). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taicron.gif

Haydon, F. (2008). Africa: natural resources [digital image]. In Giroux, J., Africa’s growing strategic relevance. CSS Analyses in Security Policy, 3(38), 1-3. ETH Zurich. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/56968/css_analysen_nr38-0708_E.pdf

HowMuch.net (2020). These maps show every country’s most valuable export. https://howmuch.net/articles/top-export-in-every-country

Leandre, C. (1897, September 25). [Cartoon of King Menelik II after his defeat of Italy]. Le Rire: journal humoristique paraissant le samedi. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4kyv&seq=493

Menelik II of Ethiopia Negusa Nagast (n.d.). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Menelik_II_of_Ethiopia_Negusa_Nagast.jpg

Menelik II, (1903, December 17). Translation of letter from Emperor Menelik II to Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o43319

S. M. Taïtou Impératrice d’Abyssinie (1896, March 29). In Le Petit journal. Supplément du dimanche. Bibliothèque nationale de France. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k716167b/f1.item

TUBS (2011, April 7). Ethiopia in Africa (CC BY-SA 3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ethiopia_in_Africa_(-mini_map_-rivers).svg

Resources

Abbatista, G. (2011, January 24). European Encounters in the Age of Expansion. European History Online. http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/backgrounds/european-encounters/guido-abbattista-european-encounters-in-the-age-of-expansion.

Abera, A. (2020, March 4). The Struggle Against Colonialism: Ethiopia’s Experience to Virtual Loss of Independence. St. Mary’s University Research Scholars. https://stmuscholars.org/the-ethiopian-struggle-against-colonialismthe-experience-to-virtual-loss-of-independence/

[Untitled oil painting depicting the battle of Adwa, March 2, 1896]. (1940-1949). The Trustees of the British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/72427001. (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Budge, E. A. (1932). The Kebra Nagast. Sacred Texts.com. https://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/kn/index.htm

Circular Letter sent by Emperor Menelek to the Heads of European States in 1891 (1891). Somalitalk.com. Retrieved August 4, 2023 from http://www.somalitalk.com/abdirisaq/circular.html

Derillo, E. (2019, October 18). Black History Month: King Menelik and Queen Taytu’s phonograph message to Queen Victoria. https://blogs.bl.uk/sound-and-vision/2019/10/black-history-month-king-menelik-and-queen-taytus-phonograph-message-to-queen-victoria.html

Hoh, A. (2020, March 31). Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia and the Battle of Adwa: A Pictorial History. Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/international-collections/2020/03/emperor-menelik-ii-of-ethiopia-and-the-battle-of-adwa-a-pictorial-history/.

Menelik II, Menelik II. (1903, December 17). Translation of letter from Emperor Menelik II to Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. Retrieved from https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o433.

Sanderson, G. N. (1964) The foreign policy of Negus Menelik (pdf). Journal of African History, 5, 429. https://mrsgewitz.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/4/7/13476108/menelik_ii_primary_source.pdf

The Berlin Conference. (2019, August 27). South African History Online. Retrieved August 4, 2023, from https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/berlin-conference.

The Scramble for Africa: Late 19th Century. (2019, August 27). South African History Online. Retrieved August 4, 2023, from https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/grade-8-term-3-scramble-africa-late-19th-century

Treaty of Wichale. (1889). SamePassage.com. Retrieved August 4, 2023, from https://samepassage.org/treaty-of-wichale/