11 Modeling Critical Thinking

Tutors spend lots of time working with students to develop critical thinking skills. Using Socratic questioning, we guide students from memory, to comprehension, to analysis and evaluation. We coach them through the problem solving process so that they make progress with their studies. Facilitating critical thinking is an important part of what we do.

It’s equally important that tutors do not forget to practice critical thinking themselves. In this section, we review the important components of critical thinking, why they’re important, and how we can actively practice critical thinking in our tutoring sessions.

Defining Critical Thinking

We use the words “critical thinking,” quite a lot, but what does it actually mean? The National Counsel for Excellence in Critical Thinking describes critical thinking as an “intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully using one’s observations, communication, and moments of reflection, to understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information.”1 Let’s break that down:

- “Intellectually disciplined”- Using the critical thinking process is a skill. It takes practice. It takes discipline.

- “Actively and skillfully”- Critical thinking is an active process. It requires intention and effort. It’s often not something we automatically do, even once we’ve developed our skills.

- “Observations, communication, and moments of reflection”- The critical thinking process begins with how we take in information. We first reflect on the things we observe, the material we read, and the exchanges we have with people.

- After we’ve made observations, we can proceed with the Critical Thinking Process. The definition lists the steps that are included in the process: “understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and synthesize.”

An important characteristic of critical thinking, as defined here, is that it is universally applicable across disciplines and situations. The same process can be applied in a science class, when reading the news, when modifying a recipe in the kitchen, or when tutoring a student. It’s a skill that we can use in all areas of our lives, and it encourages a type of introspection called metacognition. Metacognition occurs when we think about our own thinking. No matter what task we may encounter, applying critical thinking forces us to question our perceptions and reactions. It creates opportunities for us to reflect on the questions we haven’t yet asked, and perspectives we haven’t yet considered.2

The Critical Thinking Process

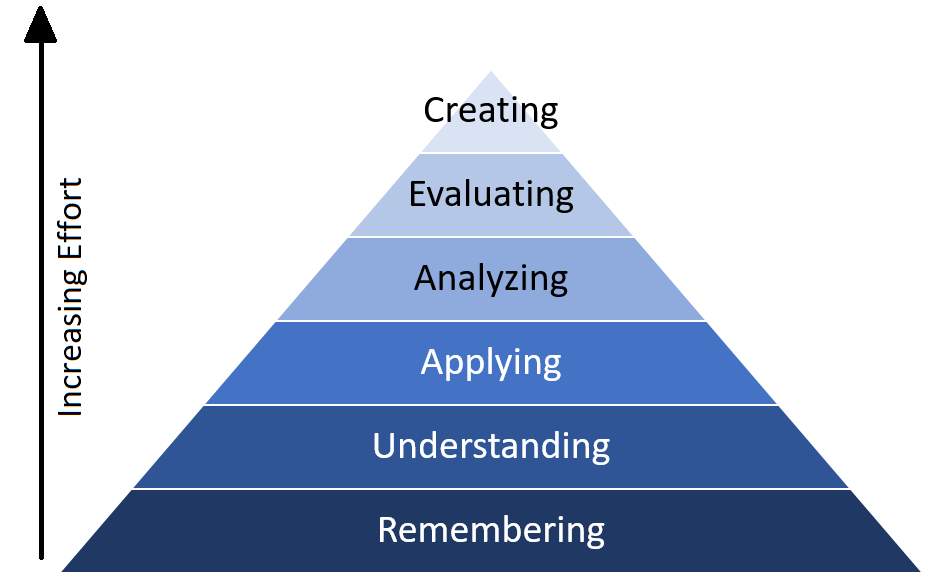

There are many models that exist to describe the critical thinking process. One Model of Learning Theory, called Bloom’s Taxonomy,3 describes the different ways we can “know” something. Bloom’s Taxonomy arranges these ways of knowing into a hierarchy according to the effort required to achieve that level of understanding (See Figure) The more critical our thinking, the higher we move up the hierarchy.

The stages of Remembering and Understanding information, require the least critical thought. These stages include the observations and reflection mentioned earlier and are preliminary to the critical thinking process. True critical thinking begins when, once we have observed new information and understood it, we begin to Apply and Analyze it.4 We test it out, place it in various scenarios, and begin to ask more probing questions. These are the stages where we “take the idea apart,” breaking it into its components to better understand what they are and how they fit together.

After a certain level of questioning, scrutiny, and reviewing information from a variety of perspectives, we can begin to make assessments, judgements, and evaluations. Evaluation calls us to bring new information into the situation. Here we’re making judgements based on our prior experience and knowledge in other areas. We also make judgements based on our personal values, our goals, and objectives.

Finally, the most critical stage of thought is the Creation or Synthesis stage. Here is where we take in everything we’ve already learned and create a new idea. Creating solutions, proposing alternatives, and generating new thoughts based on what we’ve learned requires the most effort and is the result of much critical thought.4,5

(Ideas which prove to be exceptionally bad, are likely the result of a lack of critical thought. When we skip over the lower stages of the hierarchy, and attempt to start from the very top, we miss all the critical thinking that informs good ideas.)

How Tutors Can Apply Critical Thinking

It’s easy to see how critical thinking can help students, but we may wonder how we should be applying critical thinking when we’re acting as tutors. Remember that the critical thinking process can be applied to any subject or discipline. It can also be applied to situations outside of the classroom. It’s likely that we’re using some degree of critical thinking in our tutoring sessions already. Recognizing how we already use it, and how we can more actively apply the process, lead to more effective assistance during sessions.6,7

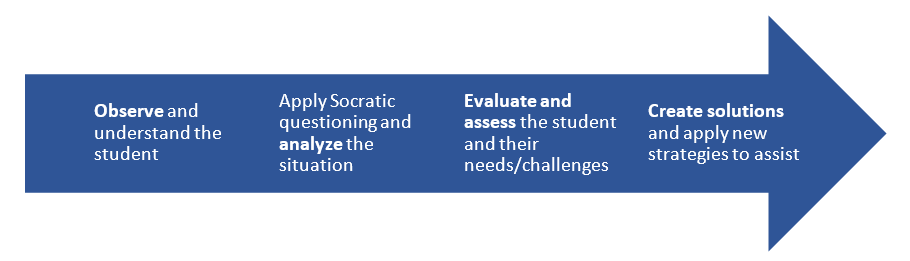

Let’s walk through what critical thinking might look like for a tutor (see Figure 2.):

We first begin with observations and information gathering. In a session, this means learning what assignment a student is working on, but also observing the student.

- Is this student new to tutoring, or familiar?

- Do they seem to be embarrassed to ask for help, or are they comfortable sharing their struggles?

- Does the student know exactly what’s giving them trouble, or are they unclear on what piece is challenging them?

- Is the student organized, or do they have trouble finding assignments?

- Can they read and understand their notes from class?

All these observations can inform how we proceed with the tutoring session, if we apply critical thinking.

Next, we move onto our Socratic questioning. In addition to giving us the opportunity to make more observations, these interactions with the student help us to better analyze the student’s situation.

- Which parts does the student understand, and which are elusive?

- Are the student’s notes organized and legible?

- Does the student struggle with the language used in their textbook?

This kind of analysis can give us a more holistic view of the student and their particular case.

After learning as much as we can about the situation, we can begin to evaluate and make assessments. This informs how we move forward with the session, and where we ask the student to focus.

- Perhaps we can confidently assess which parts of a process the student has misinterpreted, and so can guide the student to better understand them.

- Perhaps we have identified patterns in the students’ work and choose to focus our attention on addressing something more systemic, rather than working through the specific assignment.

- It might be the case that you evaluate the student’ understanding of a concept and conclude that the underlying issue is that they can’t read their notes from class, or don’t have access to the textbook, or can’t find the assignment instructions due to poor organization.

With this information, a tutor might choose to spend some time addressing these issues with the student, concluding that they are the greater hindrance to the student’s success.

Finally, the tutor moves on to the creation/synthesis stage of critical thinking. The priority for the tutor is to help the student develop their own solutions to the problems they encounter, but this doesn’t mean that the tutor isn’t creating solutions of their own.

Tutors may synthesize a new strategy or approach, in response to the evaluation the tutor has made of the student’s need.

Examples

- A student struggles to apply a math concept.

- The tutor’s solution may be to create some practice problems to demonstrate to the student how the concept is applied.

- A student struggles to understand an abstract idea.

- The tutor may devise a solution that grounds the concept in real-life scenarios or uses creative metaphors to assist the student’s comprehension.

The tutor’s creative solutions and strategies are informed by the assessments made in the previous stages of the critical thinking process. Solutions and strategies are not always appropriate or effective unless we first take time to observe, analyze, evaluate, and gain a better understanding of the student and their needs.

Quickwrite Reflection

How do you currently use critical thinking in your interactions with students during a tutoring session? Are you actively making observations and responding? Have you adapted your approach with a student based on your observations?

Take a moment to reflect on how you may already be integrating critical thinking into your interactions with students.

How can you improve your critical thinking in your interactions with students?

Pitfalls to Avoid

We can always find ways to improve, no matter how skilled we are in applying the critical thinking process. In addition, it’s important to recognize that we can also fall into bad habits in our critical thinking, if we’re not careful. Many of the habits that influence our reasoning involve unconscious biases, predispositions, and other beliefs that we may not even realize we carry.

This is where our metacognition and self-reflection become important. It’s always a good idea to remember to check in with ourselves, and ask if there are underlying factors that could be influencing our decision making. Even when we have applied critical thinking appropriately, self-awareness is important in understanding what may be influencing our observations, our conclusions, and the solutions we propose.8

Some of these factors that can unconsciously influence our critical thinking process include:

- Unintentional Prejudices

- Unconscious Biases

- Social Taboos

- Situational Distortions

- Acceptance of Established Social Norms

- Vested Interest in a Particular Outcome

- Our Own Self-Interest

Even the world’s most logical thinkers know that emotions, prior experiences, and unintentional biases can influence how we view situations. This can impact our ability to truly think critically about them. When other factors begin influencing our critical thinking, it can often be difficult to notice. How do we combat this? We can’t eliminate the influence of these factors entirely. That’s why it’s essential that we remain self-aware and maintain an attitude focused on improvement.9

What might these pitfalls look like for a tutor? Here are a few examples:

Examples

1. The tutor has a party to attend later tonight, and if they finish working with a student early, they have more time to get ready. Instead of taking time to carefully evaluate the student’s need, they apply a strategy that is quick.

Is it a bad strategy? Not necessarily. Is it the best strategy? Maybe not.

In this case the tutor’s critical thinking was influenced by their personal motivations.

2. The tutor is working with a student who has an accent. The tutor automatically begins applying strategies they’ve used for students who struggle reading texts in English.

Are these strategies appropriate here? Maybe not.

By automatically focusing on the student’s language proficiency this way, the student has skipped over the preliminary stages of critical thinking, and went directly to creating a solution. What’s more, is that the student could be offended that the tutor made assumptions about their language proficiency.

3. The tutor is assisting a student with an essay on current events. They start the session by asking helpful questions to assist the student in identifying their stance on the issue and to structure their ideas for the paper. The tutor subtly convinces the student to adopt arguments and stances that more closely align with the tutor’s own beliefs and position on the current event issue.

In this example, evaluation of the student’s situation led the tutor to use guided questioning as a strategy to help the student discover their ideas about the assignment topic. However, the tutor allowed their own beliefs about the issue to interfere with the student’s critical thinking process, sabotaging the original goal to help the student to make their own conclusions.

Something to Try

Take the social attitudes implicit bias self-assessment offered by Project Implicit® https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

Reflect on your results. Are you surprised? Did you learn something new about yourself? How do you think the results of your assessment impact how you approach your role as a tutor?

Alternatively, take a moment to reflect on the following questions:

- Think back to your childhood. Remember who your teachers were. Can you remember your school principal, your sports coaches, police officers, community leaders? When you were young, did people in positions of authority in your life look like you?

- What did your household look like? Were you raised by parents? Two parents? One parent? Grandparents? Someone else?

- Think about the movies you see. The books you read. Magazines, music, video games, and other popular media. Do the characters and people in these media look like you? Do these media explore topics that you can relate to?

- When you want to go to a new restaurant, theater, or event, how often do you have to research whether or not they can accommodate you?

Our answers to questions like these reveal the lens by which we see the world, and can help us to understand others whose beliefs and perceptions are different from our own, based on their own set of life experiences.

Effective tutoring requires tutors to be well-versed in the critical thinking process. We use the process to guide students through practicing critical thought in their coursework, and we use it ourselves in our sessions assisting those students. We simultaneously focus on the student’s thinking, and on our own approach.

A thorough understanding of the process, and the importance of each of its parts, can provide tutors a solid foundational knowledge when navigating sessions. Metacognition is an important skill in applying the critical thinking process, and self-reflection is an important component in assessing the effectiveness of our own critical thinking. With lots of practice and an attitude of continuous improvement, we can advance our tutoring skills and better assist the students with whom we work.

Notes:

- The Foundation For Critical Thinking. (2019). Defining Critical Thinking. The Foundation for Critical Thinking. http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.

- . (2014). Critical Thinking and Speaking Proficiency: A Mixed-method Study. Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 4(1), 79-87. http://www.academypublication.com/issues/past/tpls/vol04/01/12.pdf.

- Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, Krathwohl. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company. https://www.uky.edu/~rsand1/china2018/texts/Bloom%20et%20al%20-Taxonomy%20of%20Educational%20Objectives.pdf.

- Fahim and Masouleh. (2012). Critical Thinking in Higher Education: A Pedagogical Look. Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 2(7), 1370-1375. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267426179_Critical_Thinking_in_Higher_Education_A_Pedagogical_Look.

- McLoughlin, and Luca. (2000). Cognitive engagement and higher order thinking through computer conferencing: We know why but do we know how? In A. Herrmann, & M. M. Kulski (Ed.), 9th Annual Teaching Learning Forum (pp. 4-15). Perth: Curtin University of Technology. http://cleo.murdoch.edu.au/confs/tlf/tlf2000/mcloughlin.html..

- Cosgrove. (2011). Critical thinking in the Oxford tutorial: a call for an explicit and systematic approach. Journal of Higher Education Research and Development. 30(3), 343-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.487259.

- Crook. (2006). Substantive Critical Thinking as Developed by the Foundation for Critical Thinking Proves Effective in Raising SAT and ACT Test Scores. Foundation for Critical Thinking. http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/substantive-critical-thinking-as-developed-by-the-foundation-for-critical-thinking-proves-effective-in-raising-sat-and-act-test-scores/632.

- Ashwin. (2006). Variation in academics’ accounts of tutorials. Studies in Higher Education. 31(6), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070601004234.

- Anderson and Soden. (2001). Peer Interaction and the Learning of Critical Thinking Skills. Psychology Learning & Teaching. 1(1), 37-40. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/plat.2001.1.1.37.

Additional Resources:

Paul and Elder. (2020). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking: Concepts and Tools, 8th Ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Inc. https://rowman.com/isbn/9781538134955.