9 Learning Theory

When a student goes to class, their goal is to learn the material presented by the instructor. A course’s curriculum covers a number of topics, and by the end of the course the student should have increased knowledge and understanding of these topics. Tutors know, however, that actually absorbing and understanding all this course information isn’t always simple.

For many years, educators and researchers have studied how students can best learn. Today we have a variety of models that describe the many ways students learn and grow in their knowledge and understanding of course material. Learning theory describes how students absorb, process, and retain information during learning.1

There is no need for tutors to be experts in learning theory, but a basic understanding of some popular learning models can help us to better understand a student’s learning process. It can also help us to guide students in achieving a more complete understanding of their course material.

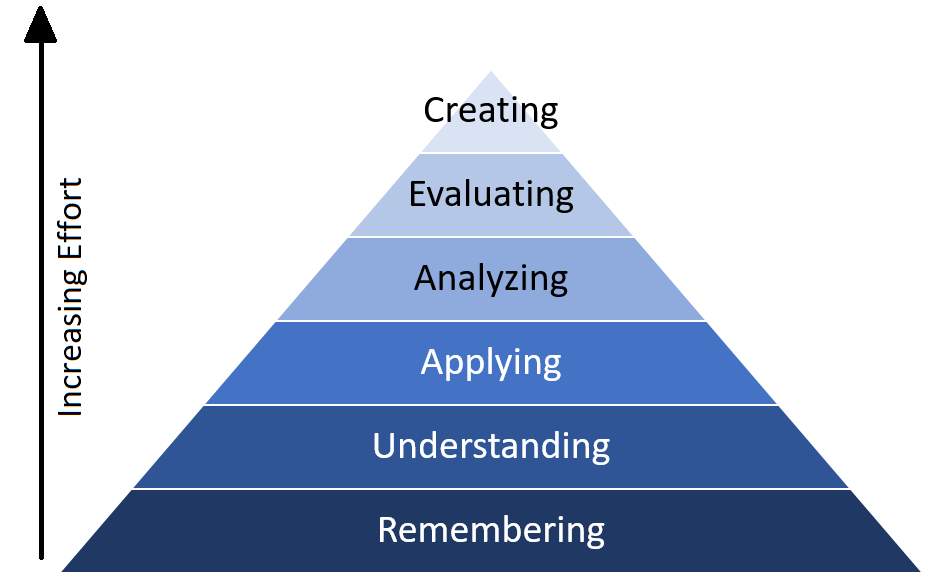

As mentioned above, there are many models that attempt to describe the learning process. A popular model of learning theory is known as Bloom’s Taxonomy. Bloom’s Taxonomy describes a hierarchy of understanding, describing various levels of familiarity and mastery of material we can achieve.2 The levels at the bottom of the hierarchy generally require less time and effort to attain, while the levels at the top require more a more complex and nuanced understanding.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

We can help guide students to higher orders of understanding by familiarizing ourselves with these levels. Recalling facts and comprehending previous problems allows a student to apply their experience to similar problems, building on their experience and advancing their understanding. For example, lower-level skills (memorizing factual knowledge, for example) can be developed before higher-level skills are achieved (analysis of relationships).3

Familiarity with these levels can also help tutors to recognize what kind of thinking a student’s assignment may be asking of them. We can better coach a student to develop the kind of thinking necessary to complete the assignment by identifying the level at which the assignment asks the student to engage.

Let’s take a close look at each level of the hierarchy:

Remembering

Remembering information is the first level in Bloom’s hierarchy of understanding. A student achieves this level when they can recall what was said in a class. It can encompass rote factual knowledge of specific words and vocabulary, the sequence of process, or the presentation of a theory.

Assignments and activities that call on students to provide definitions of key words, identify points on a diagram, or list out the steps of a process in correct order, rely on a mastery of this step.

Examples:

- Flash cards

- Labeling parts of the body

- Listing the steps of a cycle

- Reciting a foundational theory

Understanding

Understanding the meaning of information is the next step above simply remembering the information. This is the difference between being able to read the words, and being able to understand the meaning of their message.

Assignments that require students to demonstrate their understanding of material include, writing a summary, providing explanations in their own words or translating material from one format to another.

Examples:

- Writing and short summary of a textbook chapter

- Writing definitions using your own words

- Creating a diagram of a process described in a written passage

Applying

Applying information is the next level in Bloom’s hierarchy. Students reach this level when they use information, to solve new problems or respond to new situations. Application of the information to new contexts requires just a little more work than simply understanding it.

Students may work on assignments that ask them to apply information in a variety of ways. Rules, methods, concepts, principles, laws, and theories are often situated in scenarios that students will be asked to explain, and demonstrate how the rule or principle applies to the unique scenario.

Examples:

- Word problems that require students to apply mathematical or scientific concepts to real-world scenarios

- Thought experiments that ask students to extend an idea to its logical conclusion in a certain situation

- Case studies that require students to guess at what outcomes would be suggested by a certain philosophy or worldview

Analyzing

When students know information well enough to remember, understand, and apply it, they’ve reach a place where they can begin to effectively analyze it. Analysis is the breaking down of materials into their component parts so they can be examined and better understood. When students can analyze information, they are able to develop multiple conclusions about the material, taken from its different parts and how they are arranged.

Many assignments require students to demonstrate an ability to analyze given material, based on an understanding of learned concepts and an ability to apply them.

Examples:

- case studies

- simulations

- graphic organizers

- compare/contrast assignments

Evaluating

Once a student can analyze material, they are in a position to begin to evaluate it. Evaluating is the action of making value judgements about information. It requires students to base these judgements either on their personal values or opinions, or other criteria provided. This level of Bloom’s Taxonomy includes the ability to make determinations and assessments.

Assignments that ask students to evaluate often include key words in the instructions, such as “argue,” “critique,” “justify,” “defend,” “assess,” and “judge,” just to name a few. A student may also be asked to bring their own opinion to their response.

Examples:

- persuasive essays

- class debates

- class presentations

Creating

Creating is the highest level in Bloom’s Taxonomy, because it includes within it all the other categories. Synthesizing new and creative applications of prior knowledge and skills requires students to be able to master all the previous levels of the hierarchy. Students reach this level when they can take their knowledge from each previous level and use it to invent something new and original. Students will often work through the course material, advancing their understanding until they reach this stage toward the end of the course. For this reason, instructors will often assign final projects that ask students to demonstrate their ability to create original ideas.

Instructions for assignments that require students to master this level of the hierarchy often include words such as: “construct,” “create,” “propose,” “formulate,” “design,” and “hypothesize.”

Examples:

- a class presentation

- a model

- a plan

- a portfolio

- a term paper

Something to Try

The next time a student comes to you with an assignment, take a look at what the assignment requires. Where on Bloom’s taxonomy does this assignment fall? Is the student being asked to recall or look up information? Analyze? Evaluate? Synthesize? See if you can identify the kind of thinking being requested.

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a tool to better understand and guide our learning helps students to engage in metacognition: thinking about their own thinking. It can help learners to take a step back, assess where they are in their understanding of the material, and can clarify what they’re working to achieve.

It can also help tutors to be more effective. A large component of the tutoring session involves assessing what the student already knows, and where they’re getting stuck. Bloom’s Taxonomy can help us be more effective in our assessments and more helpful in coaching a student through a problem.

Quickwrite Reflection

Take a moment to reflect on some of your own learning experiences. Can you remember a time when you were being asked to learn something at the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy? How about a time when you were asked to work at higher levels?

Now ask yourself the following questions:

- How did you know you were being asked to work at a different level?

- How were those experiences different for you? Did you find one experience easier or more difficult than the other?

- In each instance, did you have to use different strategies to be successful?

Other Models for Active Learning and Critical Thinking

When we work with Bloom’s Taxonomy, we must assume that a student can improve and grow. We accept that there is progress to be made when learning about anything new. This underlying presumption is actually another learning theory, and is useful in approaching our work as tutors.

Growth Mindset

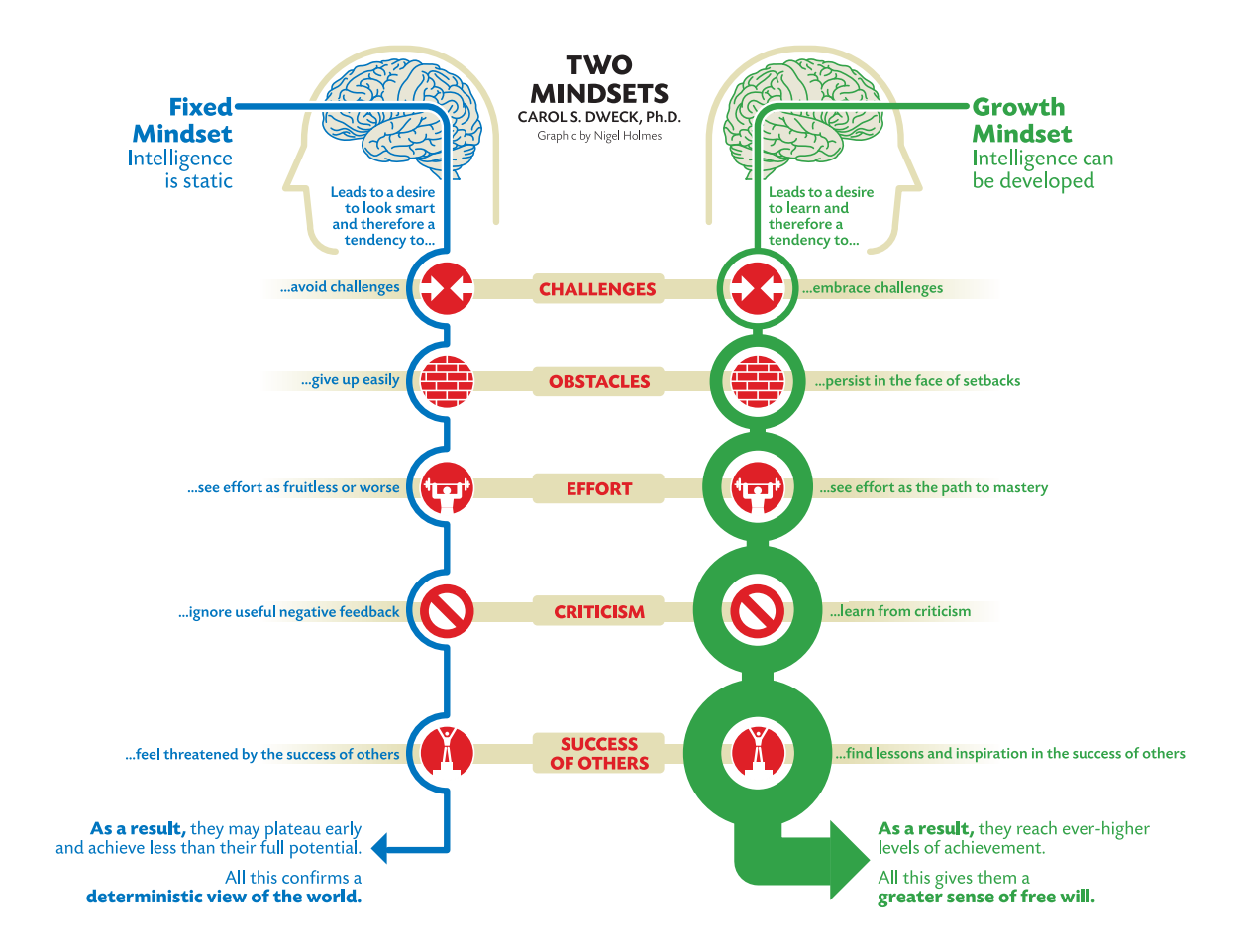

Growth Mindset is a foundational belief that learners can learn and grow and improve with enough time and practice. Whereas Bloom’s Taxonomy describes and organizes a learner’s cognitive development, Growth Mindset describes an attitude toward learning something new, and emphasizes that the mindset with which a student approaches learning is an important factor in that student’s success.4

The Qualities of a Fixed Mindset

Perhaps the best way to define a growth mindset is to illustrate what it is not. The opposite of a growth mindset, is a “fixed mindset.”

Perhaps you’ve worked with or known students who are very discouraged with their progress in class. They’re frequently overwhelmed by their assignments before they’ve even tried to work on them. This student may have a fixed mindset toward their ability to learn new things. Tutors may hear them say things like, “I’m dumb,” or “I’m so stupid,” or “Maybe I shouldn’t be in this class.” They’ll describe themselves as “not a math person,” or “I’ve never been very good at writing.”

A fixed mindset is the belief that we cannot improve upon our current abilities and that we are incapable of learning more and improving with practice. Students with a fixed mindset often believe that additional effort is pointless- and this can make motivation to undertake difficult assignments nearly impossible.5

In fact, students struggling to overcome a fixed mindset may avoid challenging work altogether. They may try to hide their shortcomings and not be fully honest about what they don’t understand about their assignments. They may be resistant to asking for or receiving help, and may have difficulty receiving suggestions or feedback.

It can be difficult for tutors to assist a student who has a fixed mindset toward their coursework because the student’s approach to learning keeps them from being able to make progress. Seeing a tutor may be a difficult and even upsetting experience for a student with a fixed mindset- and this is no surprise! If we define ourselves by our failures and inabilities, then getting assistance from someone else can make us feel very vulnerable.

How can we approach tutoring students who struggle with a fixed mindset? We can only help them to improve when they believe they can improve.

A tutor’s first step must be to help the student shift from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset. Our efforts at relationship-building and developing rapport with students become particularly important here. A student’s willingness to make changes, value feedback, and consider suggestions is predicated on establishing trust and a good working relationship. If tutors want to help a student to shift their perspective and take on a growth mindset, we have to help students to feel seen and understood.

Qualities of a Growth Mindset

Precisely how students are fixed (or “stuck”) in their mindset will be different from one student to another. Some students with a fixed mindset won’t admit to the things they don’t understand. Others will readily assume that they don’t understand anything. For this reason, the ways in which we can guide students to shift their attitude will be unique for each individual. The important thing is that we can recognize the signs that the student has a fixed mindset, and are prepared to help them reframe their thoughts in a growth-oriented way.6

Once we establish a trusting working relationship, it becomes easier to reframe fixed mindset statements and behaviors, with growth mindset perspectives.

Students with a growth mindset acknowledge and accept their weaknesses, rather than trying to hide gaps in their understanding. A growth mindset enables learners to view these gaps and challenges as opportunities for growth, and to not characterize themselves as bad students. The focus of a growth mindset isn’t necessarily to “get it right,” but to make progress. It’s based on a belief that our brains can change and grow, and an emphasis on the learning process, rather than an end result.7

Students with a strong growth mindset are open to trying new ways of learning. A willingness to adapt to an alternative learning approach can help the student to get past feelings of inadequacy and direct their focus to finding learning strategies that work for them. They know that a need for improvement is not the same as failure. A growth mindset can help learners to receive criticism in a way that allows them to make improvements, rather than taking critique as a personal attack. It also helps students to remember that improvement takes time.8

It’s often the case that we all have a combination of fixed and growth mindsets at different times, and in different contexts.9 Perhaps there are certain subjects in which we have more confidence, and so it’s easier for us to take a growth mindset toward learning new material in that subject. At the same time, we may lack confidence in another area, and have a more fixed mindset toward it. Fixed and growth mindsets, while presented here as distinct categories, are actually on a spectrum of attitudes toward learning. We can have more or less of a growth mindset, and we can always work toward further strengthening it.

| Fixed Mindset | Growth Mindset |

| “Intelligence and talent are something you’re born with and you can’t change.” | “Intelligence and talent are things that are developed.” |

| “Effort it pointless. Why even try?” | “Effort is the path to mastery.” |

| “I’m defined by my failures.” | “Mistakes are a part of learning.” |

| “I have to hide my flaws and shortcomings.” | “My failures are opportunities to grow. I don’t need to be embarrassed.” |

| “I need to avoid challenges.” | “I embrace challenges as opportunities for growth.” |

| Ignores feedback. | Welcomes feedback. |

| Takes critical feedback personally. | Uses feedback to improve. |

| Feels threatened by others’ success. | Is inspired by others’ success. |

Exercise

Take the “Theories of Intelligence” Quiz

How did you score? Do you have a growth mindset?

In what ways or in what situations do you think your mindset is more fixed?

How can you reinterpret your self-talk to maintain a growth mindset when you find yourself thinking in a “fixed” way?

Inquiry-Based Learning

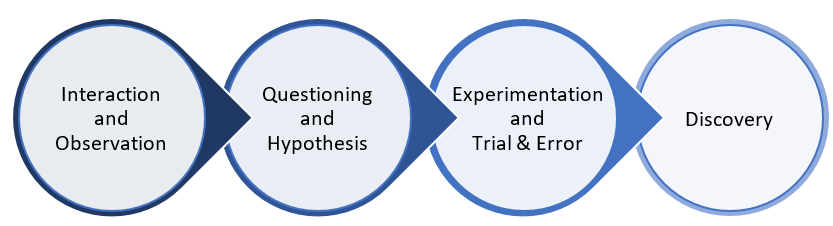

Inquiry-based learning is an approach to teaching that emphasizes the student’s role in the learning process. Rather than a teacher telling students what they need to know and why, students are encouraged to explore the material, ask questions, and share ideas.10

This approach to guided learning is very compatible with our tutoring philosophy. Tutors guide students in their own discovery of solutions through our use of Socratic questioning. More specifically, inquiry-based learning encourages the learner to take an approach similar to that of a scientist applying the scientific method. Students make connections by first asking questions, making observations, developing “hypotheses,” and discovering new relationships between pieces of information by testing these hypotheses. By using a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning strategies, students experiment with the parameters presented by a textbook or lecture, and test them in constructed applications. This is an excellent learning practice for a tutoring session, because it involves active learning through applying problem solving strategies.

This approach also emphasizes the importance of the learner taking responsibility for the discovery of new information. In a classroom lecture environment, it can be easy for students to remain at the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Information is received, recorded, memorized, and understood, but lectures and textbook readings alone may not provide opportunities for students to practice the experimentation and connection-building that is characteristic of the higher orders of thinking. An inquiry-based approach encourages a deeper engagement with the material.11

Furthermore, the more comfortable students become with an inquiry-based approach, the more confidence they can gain in their learning abilities. The scientific method is dependent on the disproving of hypotheses, and the inquiry-based approach relies on students to make mistakes, in order to uncover the true nature of concepts and information. This helps students to shift their perspectives toward a growth mindset.12

It’s often the case that students- especially adult learners- fear failure in their schoolwork. Mistakes usually have a negative impact on our grades and it’s uncommon for students to be rewarded for incorrect answers to questions. It is through mistakes, however, that we do some of our best learning. Becoming comfortable with inquiry-based exploration can help students to place their focus on the learning process, rather than on “getting it right.” It can also give learners the exposure to the failure that’s necessary for making progress in a safe and stress-free environment.

Something to Try

In your next tutoring session, try to notice how the student talks about their learning and abilities. What comments do they make? What attitude toward their assignments do they have? Are they exhibiting traits of a growth mindset or a fixed mindset?

If you are noticing a fixed mindset, try using process praise and meaningful encouragement to help them re-frame their perception.

Notes:

- Dirkx, John M. (1998). Transformative Learning Theory in the Practice of Adult Education: An Overview. PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning. 7, 1-14. https://rabu.pw/nis_n_m_s.pdf.

- Anderson, Krathwohl, Airasian, et al. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Addison Wesley Longman Inc. https://www.uky.edu/~rsand1/china2018/texts/Anderson-Krathwohl%20-%20A%20taxonomy%20for%20learning%20teaching%20and%20assessing.pdf.

- Bloom, B. S. (1969). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals : Handbook I, Cognitive domain. McKay. https://www.uky.edu/~rsand1/china2018/texts/Bloom%20et%20al%20-Taxonomy%20of%20Educational%20Objectives.pdf.

- Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5.

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist. 47(4), 302-314. https://web.uri.edu/newstudent/files/Yeager-Dweck-Mindsets-that-promote-resilience.pdf.

- Paunesku, et al. (2015). Mind-Set Interventions Are a Scalable Treatment for Academic Underachievement. Psychological Science. 26(6), 784-793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615571017.

- Yeager, D.S., Paunesku, D., Walton, G., & Dweck, C.S. (2013). How can we instill productive mindsets at scale? A review of the evidence and an initial R&D agenda. A White Paper prepared for the White House meeting on Excellence in Education: The Importance of Academic Mindsets. https://cgsnet.org/how-can-we-instill-productive-mindsets-scale-review-evidence-and-initial-rd-agenda.

- Romero, Carissa. (2015). What We Know About Growth Mindset from Scientific Research. The Mindset Scholars Network. Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. http://mindsetscholarsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/What-We-Know-About-Growth-Mindset.pdf.

- Dweck. (2016). What Having a “Growth Mindset” Actually Means. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/01/what-having-a-growth-mindset-actually-means.

- Pedaste, et. al. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review. 14 (Feb 2015) 47-61. DOI:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003.

- Gormally, Brickman, Hallar, and Armstrong. (2009). Effects of Inquiry-based Learning on Students’ Science Literacy Skills and Confidence. International Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 3(2), Article 16. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030216.

- Chiu, C.-y., Hong, Y.-y., & Dweck, C. S. (1997). Lay dispositionism and implicit theories of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.19.