Anne Tyng & Inhabiting Geometry

This chapter introduces work by the architect, theorist, and teacher Anne Tyng. It attempts to distinguish Tyng’s contributions to joint projects with the architect Louis Kahn, often attributed solely to Kahn, while Tyng worked in his office. The material complements the article by Karrie Jacobs, linked to below, as well as Chapter 2 in the Goldberger text. Goldberger’s chapter, “Challenge and Comfort” addresses Kahn’s work in detail, but does not discuss Tyng.

To Read

Author and design historian, Karrie Jacobs’ essay helps the learner understand how Tyng’s own design philosophy impacted her work. If you are using the Goldberger text, his chapter, “Challenge and Comfort,” covers Louis Kahn’s architecture in greater detail.

- Paul Goldberger, “Challenge and Comfort,” Chapter 2 from Why Architecture Matters (available as an eBook from Portland Community College Library)

- Karrie Jacobs, “Anne Tyng and Her Remarkable House,” Architect, February 12, 2018

To Watch

There are very few free and accessible online resources on Tyng, but the video below, available via Vimeo, features an interview with the architect that allows you to consider her work in her own words.

- “Five Chapters with Anne Tyng” (Los Angeles Experimental, 7:13)

Key Structures

The structures listed below complement the Goldberger textbook and emphasize Tyng’s approach to architecture. By learning about these buildings, we can see the impact of her designs on two of Kahn’s well-known works and on the remodel of her own home in the 1960s.

- Louis Kahn and Anne Tyng, Trenton Bath House, Ewing Township, New Jersey, 1955 (Goldberger text)

- Louis Kahn and Anne Tyng, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, 1953

- Anne Tyng, Tyng Residence, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1960

Architect in Focus: Anne Tyng

Anne Tyng (1920-2011) was an American architect, teacher, and architectural theorist. She taught at the University of Pennsylvania for nearly 30 years, and was one of the first women admitted to the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1942. She worked with the leading modernist architect Louis Kahn (1901-1974) from 1945-1964, together they had a daughter, Alexandra. This introduction to Tyng’s work focuses on how her interest in Platonic solids is reflected in her contributions to Kahn’s Trenton Bath House and the Yale University Art Gallery, as well as the third floor addition to her own house in Pennsylvania.

Space Frame Architecture & Platonic Solids

Tyng was known for her pioneering work in space frame architecture and her passion for mathematics, particularly Platonic solids.

Space frame architecture uses interlocking struts in a geometric pattern to support interior areas with few visible supports. This type of construction creates the feeling of inhabiting geometry. We’ll come back to this design philosophy throughout the examples of Tyng’s work presented in this section.

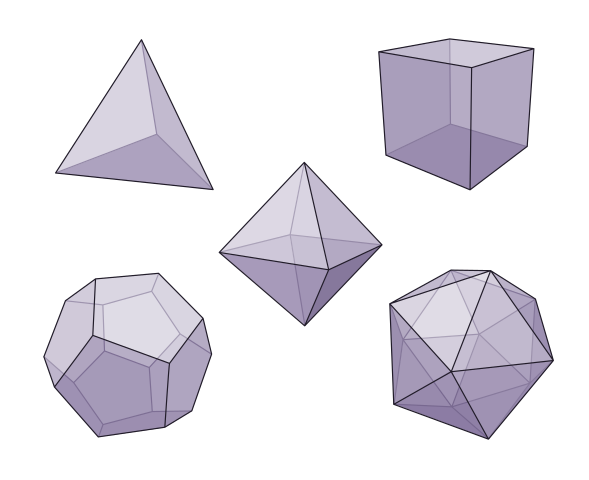

The five Platonic solids are the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, icosahedron, which are solid, three-dimensional shapes with equal sides and angles. They are also all convex shapes and every face is a regular polygon of the same size and shape (for example, each face of the cube is a square). These shapes underpin Tyng’s designs and how she conceptualized space. Her work envelopes the inhabitant, creating a feeling of living in geometric space.

Trenton Bath House, Ewing Township, New Jersey, completed 1955 (restored 2010)

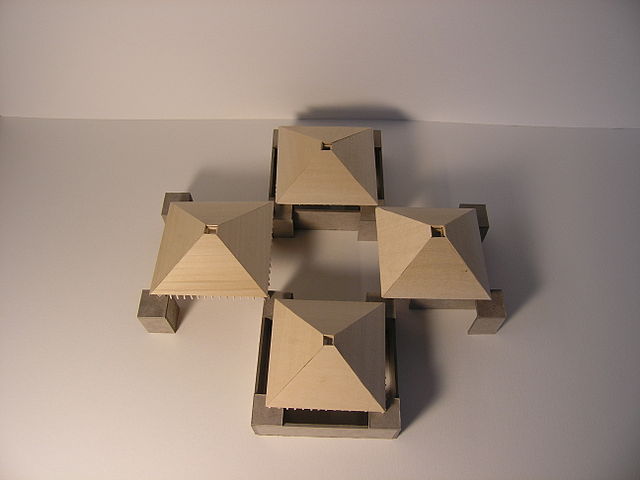

The two images above show the Trenton Bath House. These structures served an entrance and changing area for patrons using the outdoor pool at the Trenton Jewish Community Center in Ewing Township (near Trenton), New Jersey. The structure opened in 1955. While Kahn is credited as the sole architect of this project, as you read in Karrie Jacob’s essay, Anne Tyng was instrumental in the geometric simplicity of its design.

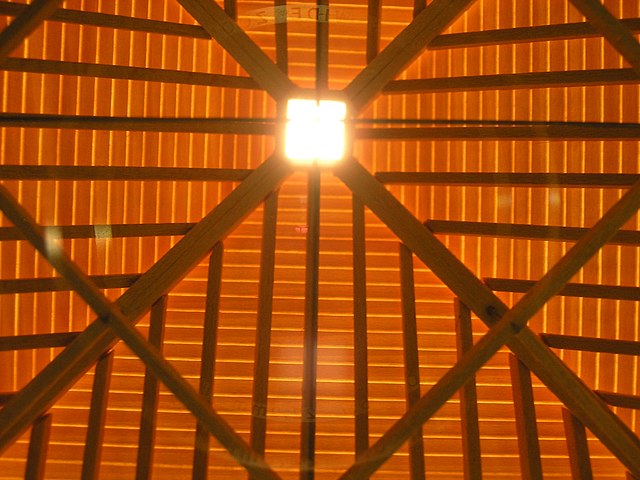

As you can see in the image above, the design of the Bath House creates the shape of a Greek cross. The four buildings meet at each corner and there is an open-air courtyard at the center. Notice, in the first picture, how the pyramidal roofs appear to float a few feet above the sidewalls, allowing sunlight to enter in through the gaps. Sunlight also streams in from above, through an open square skylight at the apex of each roof (this skylight is called the oculus, or eye, of the structure), which you can see in the image below. The space of the entire complex is interwoven, meaning the rooms are interconnected, and there are no doors to the changing rooms. Instead, each wall ends near the midpoint of the support column.

The materials used are simple: wood for the roofs and gray concrete blocks for the walls. The extended roofline, skylights, and gaps between the roof and the sidewalls, may have been influenced by Tyng’s experience with Chinese bathhouses from her childhood (her parents were missionaries and she was born in China). As is typical of Kahn’s later architecture, such as the Jonas Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, materials are allowed to weather and wear according to the elements and are left untreated. For example, part of the design at the Trenton Bath House was that water would run over the exposed masonry (to a detrimental effect on the materials). The more recent preservation of the bath house complex can be explored at the Kahn Trenton Bath House website.

Tyng Residence Third-Floor Addition, Philadelphia, PA, 1960s

The image above shows the exterior of Tyng’s former residence in Philadelphia. Tyng transformed the building’s original mansard roof into a light filled third floor addition that juts out over the sidewalk. Take a look at the use of wood under the balcony; this use of simple, straightforward materials is carried out in much of Tyng’s designs, and is echoed in earlier work, such as the Trenton Bath House.

Tyng began remodeling this home in the 1960s and the third floor addition reflects her interest in space frame architecture and interlocking geometric forms. Tyng is also focused on light; she’s added skylights and frosted doors that lead out to small, Juliette balconies, one for each wall. She also played with shape by creating triangular windows above a sleeping nook and a pyramidal timber-framed ceiling. The ceiling’s design is reminiscent of the Trenton Bath House, which is discussed above.

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, 1947-1953

At the Yale University Art Gallery, a complex ceiling of concrete tetrahedra floats over oak flooring, coming to rest on glass and brick walls. The design of the ceiling is an indelible contribution to the overall architectural language of the space, and was likely inspired by the teachings of Buckminster Fuller, who Anne Tyng studied with at the University of Pennsylvania.

As you examine the image of the interior of the art gallery below, notice how the robust forms of the ceiling compare with the works of art on view. What do you observe about how these different shapes interact? Next, compare the concrete ceiling with the glass windows. How do these parts of the structure inform the overall feeling of the space?

Looking back to Tyng’s Pennsylvania home, as well as her work on the Trenton Bath House, we can see how geometry has informed her designs. From the pyramidal rooflines hovering above the bathers at Trenton, to the deeply recessed tetrahedra pressing down on the gallery space below at Yale, Tyng shapes space using geometric forms, playing with the contrast of solids and voids.

Like the skylights and frosted doors that Tyng used in her own home, the gallery also reflects the importance of different kinds of light to interior architectural space. Light comes in, not through banks of clear glass windows, but indirectly, forcing its way through screens, panels of mesh, and concrete slabs. Yale University Art Gallery is also an early example of the use of track lighting in a gallery space, where works of art are illuminated strategically from above. Looking at images of the interior of the gallery, what is the effect of this mix of natural and artificial lighting?

Conclusion

Anne Tyng brought a sense of formal geometric principles to her own designs and to her work with Louis Kahn. She created spaces where the occupant could experience enveloping geometric forms. She rejected flat vertical walls for more experimental shapes inspired by Platonic solids. She was an architect and a theorist whose works embody a sense of inhabiting geometry.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, learners should be able to:

- Use an example of Anne Tyng’s work to describe her use of geometric forms.

- Describe what it means to inhabit geometry.

- Consider how light is use to express architectural form.

- Compare and contrast Louis Kahn and Anne Tyng’s careers in the architecture field.