4.5 Sequential Intercept Model

Diversion timing and opportunities are illustrated in the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM). The SIM was developed within the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as a project of its GAINS Center for Behavioral Health and Justice Transformation. SAMHSA is an agency created by Congress in 1992 to make information about substance use and mental disorders more accessible. The GAINS Center within SAMHSA is a government effort aimed at increasing community resources for justice-involved individuals via support and training for mental health professionals and organizations at all levels of government. The goal of SAMHSA/GAINS is to “transform the criminal justice and behavioral health systems” and recognize and seek to reduce the problem of criminalization of mental disorders (SAMHSA, 2022a). You will see many references in this chapter and throughout this text to SAMHSA resources.

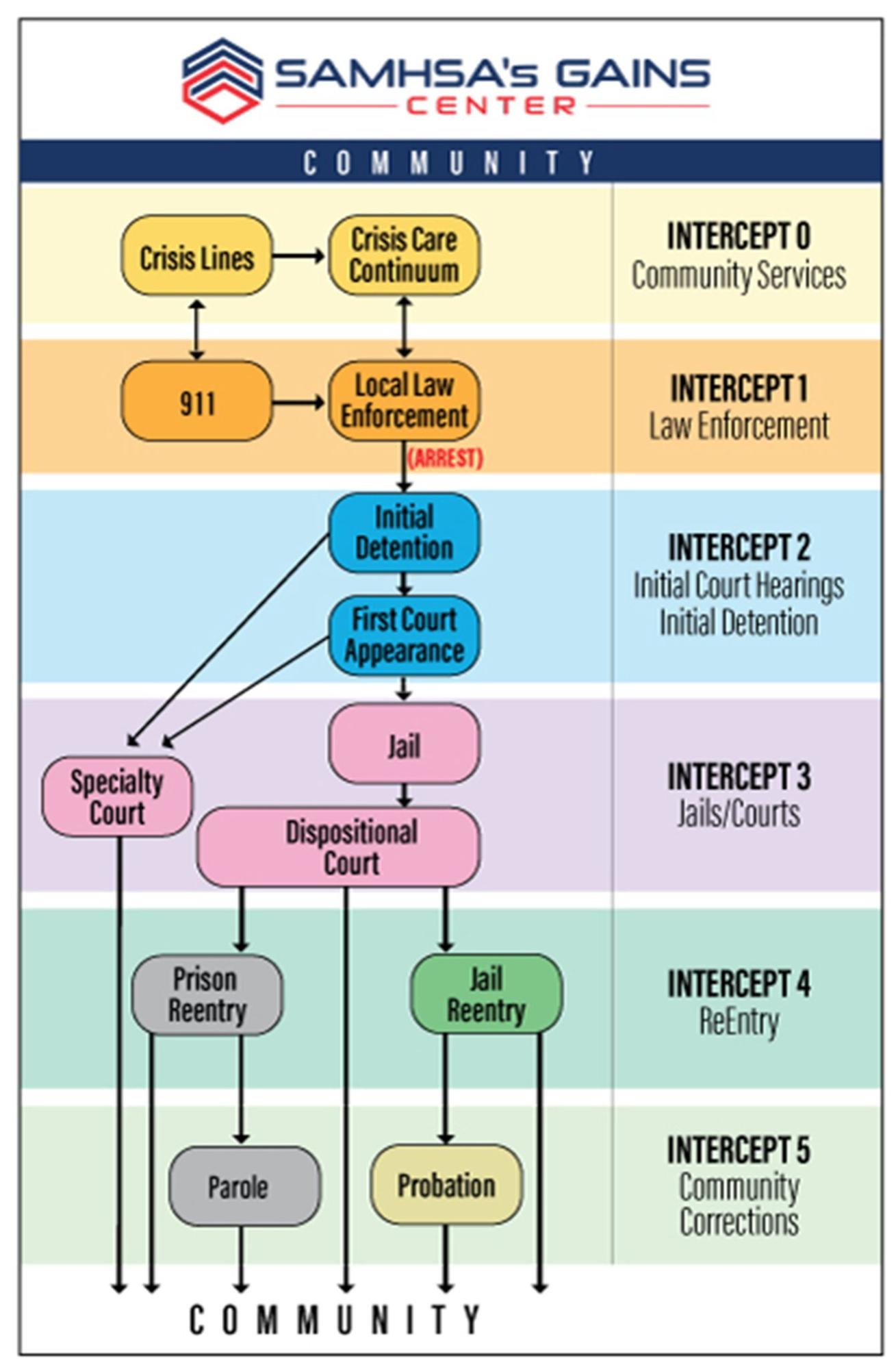

In practice, the SIM is a valuable tool for discussing and assessing various diversion options that may be available in, or missing from, a community (figure 4.10).

The SIM illustrates how exit from the criminal justice system can occur at several points in time, from the beginning to the end of a typical pathway through that system. Each intercept within the SIM represents a window in time during a person’s interaction with the criminal justice system when that person might be provided with direction or opportunity that can divert the person away from the justice system (SAMHSA, 2022b).

The SIM helps us visualize and consider each window in time when intervention and diversion might occur as a person proceeds through the criminal justice system. The specific diversion opportunities that may be available at each juncture are dependent upon the needs of the individual at that time, as well as the desires and resources of the community. Every community can look at the SIM and consider these important questions:

- Do we have diversion opportunities present at intercepts we consider most valuable?

- What opportunities or resources are missing?

- Where we lack diversion opportunities, can those be added or can others be shifted to maximize impact?

Because diversion involves cooperation from different agencies and groups who play roles in the process, creating diversion opportunities requires input and participation from an array of professionals, including first responders, mental health workers, and criminal justice professionals (Oregon Center on Behavioral Health and Justice Integration, 2023).

Each intercept in the SIM is briefly described in the following sections, with a link to the corresponding intercept discussion on the SAMHSA website. Please take a look at SAMHSA’s information on the SIM [Website] generally. As you consider each intercept point discussed below, follow the specific link provided in that section to see examples of diversion programs at that intercept point.

Community Services (Intercept 0)

The very first intercept point, Intercept 0, Community Services [Website], is the only opportunity in the SIM that allows for avoidance of the criminal justice system entirely. This intercept was added to the model in 2017, several years after the SIM was initially developed, and it focuses on the first recognized need for service, or the point where a crisis is identified (Pinals & Felthous, 2017). Intercept 0 suggests responses that fully eliminate the need for police presence, never opening the door to the criminal justice system or the enormous risks that police encounters present for those with mental disorders. Community service responses such as hotlines or crisis lines (figure 4.11) are part of Intercept 0 (SAMHSA, 2022b).

Peer-support programs, self-referral substance use programs, and respite homes that allow short stays for those in need of help would all fit into Intercept 0 as well (SAMHSA, 2022b). Yet another Intercept 0 option involves the various police alternatives that are increasingly being developed in cities throughout the country (Turner, 2022). Police alternatives are discussed further in Chapter 5. The key to Intercept 0 is an intervention that takes place and supports a person’s access to treatment without the threat of an arrest.

Law Enforcement (Intercept 1)

Before Intercept 0 was added to the SIM, Intercept 1, Law Enforcement [Website], was the first imagined opportunity for diversion out of the criminal justice system. (For more information and history, if you are interested, see Using the Sequential Intercept Model to Guide Local Reform [Website].)

Intercept 1 focuses on policing as a tool that can be used for far more than just arresting people (figure 4.12). Intercept 1 imagines police serving as a filter of sorts: arresting people who need to be taken into criminal custody, while performing a protective or supportive role for others who may have been referred to or otherwise come to the attention of law enforcement but are not well-served by arrest. Of course, police have always had discretion to operate in this manner, but Intercept 1 emphasizes this opportunity and encourages skilled, informed, and community-supported approaches by law enforcement. Police use of discretion and resources to keep interactions non-coercive and non-violent increases safety for people who experience mental disorders, as well as for police themselves.

One of the most prominent aspects of Intercept 1 is training law enforcement to de-escalate mental health crisis situations, without the use of force when possible and with the goal of avoiding an arrest (SAMHSA, 2022b). Programs integrating crisis management training have been developed over the past several decades, and some police departments, such as the Portland Police Bureau, now require all officers to complete a 40-hour training specifically targeted to interactions with people with mental disorders. Co-response teams, in which law enforcement officers are paired with mental health professionals to respond to and manage calls involving mental disorders, are also an increasingly favored Intercept 1 approach (SAMHSA, 2022b). These options are discussed further in Chapter 5.

Initial Detention and Initial Court Hearings (Intercept 2)

Intercept 2, Initial Detention and Initial Court Hearings [Website], is focused on diversion opportunities for people who have been arrested and are facing initial criminal court appearances (figure 4.13). Here, the emphasis is on screenings or evaluations to identify the presence of mental disorders and substance use disorders, as well as on efforts to avoid or minimize time in custody.

Pretrial services in both the federal and state court systems would be considered an Intercept 2 diversion, as these programs allow a person to be supervised in the community while awaiting resolution of criminal charges (SAMHSA, 2022b). If the person is suitable for community supervision (not likely to fail to show up in court or present a danger to the community), they would be released and required to follow certain conditions. This approach allows the person to avoid the negative impacts of jail while potentially benefitting from appropriate community-based treatment or services. A pretrial officer would be charged with supervising the person as they move through the court process. The person is not convicted of any offense at this stage, so it is still possible that charges could be dismissed in a resolution of the case.

Jails and Courts (Intercept 3)

As the focus shifts to Intercept 3, Jails and Courts [Website], the SIM highlights diversion opportunities for people who are facing resolution of charges for offenses (figure 4.14). Examples would include jail-based treatment programs or treatment courts, such as drug courts, veterans’ courts, or mental health courts, which are discussed in more detail in the Spotlight in this section (SAMHSA, 2022b).

A common criticism of diversion at this intercept, especially in treatment courts, is that defendants may be required to admit guilt and face conviction or punishment should the diversion not succeed. Here, the threat of criminal justice consequences is often used as leverage to ensure the participant’s cooperation in the diversion process. In other words, a person who has been required to admit to wrongdoing to qualify for diversion may be motivated by fear of conviction or incarceration if they do not follow through with the diversion program. Is this a helpful tactic? Some consider it an opportunity for defendants that also prioritizes public safety. Others argue that this type of leverage, or threat, is an inappropriate way to ensure treatment engagement.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, most diversions are imperfect, and most could be improved in some respects by simply happening earlier, thereby avoiding interactions with law enforcement, incarceration, and/or creation of a criminal record with the impact on life opportunities that entails. For an alternative visual model, consider taking a look at this article from the Prison Policy Initiative [Website], which uses a non-SIM “highway” model to discuss diversion opportunities (conceived as “exits” off the highway) and develops the argument in favor of earlier diversion to maximize participant choice while minimizing criminal justice engagement.

SPOTLIGHT: Mental Health Courts

One Intercept 3 option is the mental health court. Mental health courts, modeled after other treatment or problem-solving courts (e.g., drug courts) focus on resolving an underlying problem rather than punishing an individual as a response to offending conduct. Like traditional criminal courts, mental health courts are overseen by a judge, the participant is represented by an attorney, and a prosecutor represents the state. The court’s focus, however, is on case management and connecting the charged person with community support, job opportunities, and treatment—all supervised by the court.

These problem-solving courts follow the longtime example of juvenile courts in considering not just what a person did but also why a person behaved in a particular way, using the court system to support sustainable behavior changes with treatment and intervention rather than incarceration and an eventual return to offending. A person may be given the opportunity to participate in mental health court when they have an identified mental disorder and have been charged with a less serious offense that is appropriate for this more informal approach.

As noted earlier in this chapter, some advocates criticize later-stage diversions such as mental health courts, voicing concern that these criminal justice-involved efforts detract from more proactive community mental health initiatives (Bernstein & Seltzer, 2003). Like all diversions, mental health courts have flaws, and one concern around this diversion approach is that it may actually encourage arrest and justice system involvement by providing support in that context when support may be harder to access outside of the system.

Watch the 13-minute required video about a mental health court (linked in figure 4.15), and consider the pros and cons of these courts, as well as other later-stage diversions. Ask yourself these questions:

- Are the potential benefits to the person and their community worth the risk of deeper engagement in the criminal justice court system? Are there benefits to this level of criminal system involvement?

- Do you agree with the Minnesota judge in this video, who believes that mental health court offers an alternative to a “revolving door” to prison? How specifically do mental health courts accomplish this?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvufZsC7Yas

There are thirteen mental health courts [Website] in Oregon, including the Multnomah County Mental Health Court [Website] in Portland, which is overseen by Circuit Court Judge Nan Waller [Website] as of this writing (Multnomah County District Attorney, n.d.). If you are interested, you may follow the links to read more about these specific courts. You may also contact your local court to arrange a visit. Courts are generally open to the public and welcome interested student observers.

Reentry (Intercept 4) and Community Corrections (Intercept 5)

The later intercepts modeled in the SIM, Intercept 4, Reentry [Website], and Intercept 5, Community Corrections [Website], are more focused on community success after a person has moved through the criminal justice system—issues that are addressed in more detail in Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 of this text (figure 4.16). In these final opportunities for diversion, a person is not so much avoiding criminal justice involvement and consequences (as those have already occurred) as they are seeking to lessen the problems associated with, and even benefit from, their justice system involvement. The focus at these intercepts is on reducing reoffending that will return the person to the criminal justice system. Diversion programs should be particularly aimed at preventing reoffending related to mental disorders. This is no small task as, overall, offenders released from state prisons typically reoffend at a rate of 83% within 9 years of release (Alper et al., 2018).

At Intercept 4, the SIM focuses on reentry preparation as a person is in the process of leaving jail or prison and reentering the community. Efforts to create success in reentry should begin during incarceration and continue in the community. Diversion efforts at Intercept 4 may involve planning to meet a person’s mental health, medical, or other basic needs (SAMHSA, 2022b). Without needed medications or other treatment in the community, people with mental disorders are more likely to engage in new offending behavior and find themselves winding through the criminal justice system once again (Weatherburn et al., 2021).

Intercept 5 focuses on community corrections, which refers to a system of oversight outside of jail (probation) or after serving time in prison (post-prison or parole) in the community. A person under this type of supervision will have particular conditions they must fulfill to remain in the community, and they can be sanctioned by the court or a supervising agency, potentially landing the person right back in custody.

One important aspect of any diversion at Intercept 5 is ensuring that supervising authorities are well-trained and attuned to the needs associated with mental disorders. For example, probation officers may carry specialized caseloads of clients with identified mental health needs, allowing them to focus on collaboration with partner agencies and community organizations that can help their clients succeed (SAMHSA, 2022b).

As one Oregon example of an Intercept 5 effort, the Multnomah County Mental Health Unit provides community supervision services for people with serious mental disorders. The Mental Health Unit partners with other agencies and organizations that support and treat this population, including treatment providers, law enforcement, defense attorneys, courts, and advocacy groups like NAMI. The goal of the Mental Health Unit is to increase community safety while reducing criminal reoffending and mental health relapse. Feel free to read more about the Mental Health Unit [Website] here.

Medication-based treatment for substance use disorders, in both jail and community settings, is a critical Intercept 4 and 5 intervention that has been shown to reduce the enormous risks of relapse and overdose in people dependent on opioids and alcohol (SAMHSA, 2022b). Interventions like this increase safety and may help reduce recidivism. Medication treatments for substance use are discussed in detail in Chapter 8.

Licenses and Attributions for Sequential Intercept Model

Open Content, Original

“Sequential Intercept Model” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: Mental Health Courts” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.10. https://www.samhsa.gov/criminal-juvenile-justice/sim-overview by SAMHSA is in the public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 4.11. Image of smartphone by OpenClipart-Vectors is licensed under the Pixabay license.

Figure 4.12. Image of police car by Clker-Free-Vector-Images is licensed under the Pixabay license.

Figure 4.13. Image of handcuffs by Clker-Free-Vector-Images is licensed under the Pixabay license.

Figure 4.14. Courtroom images by Mohamed_hassan is licensed under the Pixabay license.

Figure 4.15. A Rare Look Inside a Mental Health Court, Blue Forest Films is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 4.16. Image of a house by OpenClipart-Vectors is licensed under the Pixabay license.