2 Curiosity, Commerce, Conquest, and Competition: Fur Trade Empires and Discovery

Early European Interests

After Columbus claimed some of the Caribbean Islands for King Ferdinand and Queen Isabela, the Spanish Empire zealously pursued gold and wealth in the Americas. The conquistadors carved out land claims, established missions, coerced indigenous people through labor contracts and searched for thoroughfares to Asian trade markets. The Spaniards thought a fabled Northwest Passage, known as the Strait of Anián, crossed the North American continent linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In 1592, Ioannis Phokas of Valerianos, from the Ionian island of Cephalonia in Greece, sailed a Spanish ship to what is now Washington state. He claimed he discovered the Northwest Passage, a strait which would bear his Spanish name, Juan de Fuca. Many conquistadors and Spanish explorers had sought the imagined Strait of Anián, without success, but it was Phokas’ discovery that brought further intrigue to the lands of the Pacific Northwest and the insatiable interests of commerce and conquest among European empires.

Western European nations developed their global imprint on overseas possessions and aggressively attained claims to trade networks by asserting an expansionist nationalism. Commercial interests in the global fur trade beckoned Russian, Spanish, and British adventurers who established points of possession, portages, and trading posts by official declarations in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. The Danish explorer Vitus Bering under the czar’s service made incursions into the Northern Pacific Sitka region of Alaska and the Bering Strait. The Russian empire established fur trading outposts and were belligerent towards the indigenous peoples pressuring them to produce furs or face violent retribution towards their women.[1] Western European powers guided by Roman legal tradition (uti possideits), created rituals of possession based on conquest and subsequent demarcation of borders through the use of rock edifices scripted by official representatives of the crown or buried capsules of parchment documents. These official formal means of declaration provided the explorers and their entourages the legal means of possession in the European-American legal tradition of colonization and imperial expansion.[2] Robert Miller, a scholar of Native American and international law, refers to this as the Doctrine of Discovery.[3] The Spanish initiated this method of imperial possession in the Americas and other European powers (Russians and British) followed suit in their mastery of conquered lands and the dispossession of indigenous peoples.

Spain and Great Britain were vying superpowers that sought to have a role in the colonization of the Pacific Coast of the North American continent; however, the Spanish Empire was in decline and prospects for the British Empire looked optimistic. Seafarers from Europe and America dispelled the fog of geographic ignorance that had previously shielded the north Pacific coast from outsiders. The British government subsidized growth in overseas markets with financial incentives. In 1744, Parliament offered a reward of £20,000 to the captain and crew of the first British merchant ship to pass through the Northwest Passage, and later the offer was extended to navy ships as well. The British explorer James Cook sought the reward on his third voyage in 1778, but he personally did not think the Northwest Passage could be found.[4] Captain Cook would serve as a driving wedge between Spain and England. As Spain gradually lost sovereign influence, this allowed the United States to isolate foreign rivals from the Pacific Northwest, and narrow down their competition to England. Cook received protection from the American patriots during the Revolutionary War and safely reached the Northwest coast in search of the Northwest Passage. Orders were given to “treat his crew with all civility and kindness, affording them as common friends to mankind.”[5] After the completion of his third voyage, he provided a modern map of the region which served as an advertisement for the Oregon Territory.

During the Qing Dynasty the sea otter fur trade was in high demand. Among the Chinese nobility, the quality and tailoring of the fur denoted a person’s social rank. Furs were worn by the Chinese elite, while commoners in China wore heavy sheepskin for warmth. The Pacific Northwest sea otter was regarded as one of the finest of furs, it is little wonder that the fur traders of Boston and the British Empire pursued the Chinese market in the late eighteenth century. When Cook and his ships arrived in Canton, China, he reaped a tremendous profit from the sale of twenty otter pelts and furs estimated at thousands of dollars. Cook understood the fur trade could bring prodigious wealth to the British Empire, “The fur of these animals…is certainly finer and softer than any we know of.…The discovery of this part of the continent of North America, where so valuable an article of commerce may be met with, cannot be a matter of indifference.”[6] Connecticut-born, John Ledyard, a young explorer who served on Cook’s third voyage published his own account it, and encouraged the formation of American fur trading companies stating, “Skins which did not cost the purchaser sixpence sterling sold in China for 100 dollars.”[7]

Another British explorer, Major Robert Rogers of the British army, had become convinced the legendary Northwest Passage existed. He called it “Ourigan” and thought it connected with the Missouri River. Jonathan Carver, who served with Rogers, used the word “Oregon” for a great river that he had never seen in a book he published in 1778. Carver’s book contains the first known record of the word “Oregon” as a name that implied “river of the west.” That same river was officially designated the Columbia after Robert Gray’s voyages.[8] Later, President Thomas Jefferson wanted Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to prove if the Missouri River connected with the Columbia.

Robert Gray, a fur trader from Boston, set off on a prospective voyage to gain a foothold in the fur trade markets of the Pacific Northwest in 1792. Gray documented critical cartographic data of the Oregon region and the Columbia River. His discoveries amount to one of the foundational pieces of evidence affirming American possession of the region according to international law and the Doctrine of Discovery. American companies from New England were developing economic interests in the Pacific Northwest well before Jefferson annexed the Louisiana Purchase and Lewis and Clark’s transcontinental journey. Starting in 1787, the Pacific coast had become a target of many New England merchants and traders. They began to compete with British trading interests in the region, and made efforts to fend off the opposition in the Hudson Bay Company and Russian markets.

Robert Gray helped establish the United States as an emergent commercial power in the Northwest, and his discoveries were significant but not without controversy. Gray’s second voyage to the Columbia River marked the first landing by white men in Oregon country and was the first circumnavigation of the globe by an American ship.[9] Captain Gray piloted the ship Columbia Rediviva and his commodore John Kendrick the Lady Washington. Gray made two voyages to the Pacific Northwest over a five-year period. In 1788, Gray first anchored off Tillamook Bay near present-day Cape Lookout. They encountered Chinook and Tillamook Indians who were scarred from smallpox after coming into contact with the Spanish explorer Bruno de Heceta and his crew in 1775. Heceta was the first European to sight the mouth of the Columbia River, but his depleted crew were unable to overcome the swift currents of the mighty river.[10] Indians traded beaver skins with Gray, but not otter pelts.[11]

Gray traded with the Clatsop and the Tillamook Indians, and left behind a trail of death. Twenty natives were killed during Gray’s mission because of his fear of the Indians. On two separate occasions in Tillamook Bay (his men named it Murderer’s Harbor) and Grays Harbor, he fired on resistant Native traders, killing several. Gray’s Fifth Mate, John Boit recorded the violent altercation in his log: “I am sorry we was oblidg’d to kill the poor Divells, but it cou’d not with safety be avoided.”[12] Gray justified his actions as “taking no chances” that could jeopardize his mission. He failed to work diplomatically with the Clatsop and Tillamook who were shrewd dealers and discriminating consumers. Sometimes Indians resorted to violence to protect borderlands, resources and trading positions, and Gray’s inexperience caused unnecessary Indian deaths.

Historians of the early twentieth century have glossed over Gray’s violent interactions with the Indians and embellished his heroic qualities as a great American patriot who brought civilization to Oregon, “The discovery of the Columbia River completes at the end of a 300-year period the full discovery of America which in 1492 Columbus had initiated. The Western continent in its essential features as a home for civilized humanity was now revealed.”[13] Robert Gray’s primary interest was to find a trading post site for merchants and investors in the fur trade. He did not have a knack for diplomacy or nation building, and wasn’t interested in cultivating relations with the indigenous people.

British explorers George Vancouver and William Broughton, a member of Vancouver’s naval expedition, contended that Gray did not enter the river but only its “sound,” or estuary. They argued Broughton staked a more significant claim for the British crown on the Columbia River near the confluence of the Washougal River on October 30, 1792 about 100 miles upstream. The following month, Broughton, commandeering the HMS Chatham, was the first Euro-American to embark on Sauvie Island, near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers that frame the city of Portland today. American politicians refuted the British claim of possession of the Columbia River. South Carolina statesman and firebrand, John Calhoun challenged Great Britain that Robert Gray’s discovery of the Columbia was something that John Bull, Britain’s version of Uncle Sam, could not counter. Calhoun represented the jingoist faction of the American Democratic party that zealously promoted American expansion and was defiant to British interests in the Pacific Northwest. President James Polk aggressively disputed American claims in Oregon country with Great Britain by stating negotiation should only favor their own interests, “the only way to treat John Bull is to look him straight in the eye.”[14] Historians concluded Gray did not take possession of the Columbia River through any formal act, pointing to a journal entry in Boit’s log that contains an interlineation, “& take possession,” entered at a later date in different handwriting and different ink:

“I landed abrest the Ship with Capt, Gray to view the Country, & take possession leaving charge with the 2d officer – foind [sic] much clear ground fit for Cultivation, the woods mostly clear from Underbrush none of the Natives came near us.”[15]

If the journal entries were analyzed by a graphologist, then this could have had tremendous implications on the settlement of the Oregon boundary between Britain and the United States. The words “& take possession” were added by John Boit and were cramped in a small space; there are such interlineations throughout the journal. The second officer, Owen Smith, did not indicate that Boit went ashore with Captain Gray, but insisted Gray was the first to sail up the Columbia River. The ship’s log made no mention of burying coins (a standard procedure for marking territory by possession) or raising the American flag. Instead Boit noted in the ship’s log that the lower Columbia would make a fine “factory site” for the fur trade. A few years later, New York real estate entrepreneur John Jacob Astor fulfilled that vision (despite initial failure) and established a town named after him, Astoria.

LEWIS AND CLARK

A year after Robert Gray’s expedition to the Columbia River in 1792, Thomas Jefferson and the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia underwrote and sponsored the French botanist André Michaux to go on an overland journey along the Missouri River westward to the Pacific Ocean. Benjamin Rush and Jefferson had “framed instructions for his observance,” but the expedition never got off the ground. Jefferson’s instructions to Michaux were built upon the discovery of Robert Gray and were similar to the orders he gave to Meriwether Lewis a few years later:

“You will then pursue such of the largest streams of that river, as shall lead by the shortest way, & the lowest latitudes to the Pacific Ocean. When, pursuing these streams, you shall find yourself at the point from whence you may get by the shortest & most convenient route to some principal river of the Pacific Ocean, you are to proceed to such river, & pursue its course to the ocean. It would seem by the latest maps as if a river called Oregon interlocked with the Missouri for a considerable distance, & entered the Pacific ocean…But the Society are aware that these maps are not to be trusted.”[16]

The prominent men of the young republic who belonged to the American Philosophical Society had wider interests than the fur trade. The American Philosophical Society saw the exploration of Oregon as an Enlightenment principle of human ingenuity and as proof of the march of progress and civilization. Alexander Ross, who later accompanied John Jacob Astor’s expedition to Astoria, summarized the Enlightenment ideals of American exploration: “The progress of discovery contributes not a little to the enlightenment of mankind; for mercantile interest stimulates curiosity and adventure, and combines with them to enlarge the circle of knowledge.”[17] Discovery was a part of the noble dream of progress, expansion and societal perfection in Western liberal ideology.

Americans, along with Jefferson, became engrossed in explorer’s journals and travel literature. Alexander Mackenzie published his journals Voyages from Montreal 1789–1793. It was a powerful declaration of British intent to secure the fur commerce of the Columbia River and place a virtual monopoly of the fur trade endangering American interests in northwestern territories. Alexander Mackenzie stated: “By opening this intercourse between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and forming regular establishments through the interior, and at both extremes the entire command of the fur trade may be obtained.”[18] The Scotsman Mackenzie hadn’t found the Columbia River or any of its tributaries; thus, his voyage did not give England any claims to the Columbia River watershed. Jefferson and his personal secretary Meriwether Lewis carefully read over Mackenzie’s book. As Jefferson was seeking Congressional approval for funding the Corps of Discovery, passages of Mackenzie’s text were read in debates by politicians indicating a need for American exploration in the northwest. Mackenzie recommended that England exploit the route he had pioneered, occupy the Pacific Northwest, and open a direct fur trade with Asia on the Pacific Coast. This brought a level of urgency to President Jefferson’s decision to order Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery to stake their claims on the Columbia River.

People of the Pacific Northwest honor Lewis and Clark above all others from the era of American exploration. Cities and counties, rivers and peaks, streets and schools all attest to the importance of the two explorers and the Westernizing impulse in American life. Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery was a military expedition not built on conquest, but discovery and enlightenment. Along the path to the Oregon Territory, Lewis and Clark sought to establish trade networks, transportation and communication channels with the Indian tribes, and the legal claims of Robert Gray. They were agents, diplomats and prospectors of a blossoming American empire The fantasy of an easy portage from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean fired Jefferson’s imagination until Lewis and Clark disproved the existence of a Northwest Passage. Ultimately they accomplished their primary goal and established a permanent American presence at Fort Clatsop.

Their primary instructions involved diplomatic negotiations with Native Americans and their governments, and demarcation of land through rituals of possession. “The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, and such principal streams of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregan [sic], Colorado, or any other river.” Jefferson highlighted the pursuit of the Northwest Passage for the Asian fur trade and falsely stated to England, France, and Spain the commercial purposes of the expedition; he indicated the expedition’s sole purpose was science and exploration. Spain felt something was suspicious with American intentions and sent four military missions to stop the expedition.

The Corps of Discovery was shrouded in secrecy and intrigue. European powers were intent on expansion of their empires, and American actions had to be covert. Jefferson sent a secret message to Congress in which he sought approval and funding for the expedition. In the message, Jefferson referred to England as “that other country”[19] and requested an appropriation of $2,500 to finance an expedition up the Missouri River and to the Pacific Ocean. Historian Stephen Dow Beckham stated, “The United States had embarked on the path of building a transcontinental empire,” and the expedition “dramatically enhanced the United States discovery rights to what became known as the Oregon country.”[20] It was a carefully planned scientific reconnaissance.

Jefferson instructed Lewis and Clark to have positive relations with the tribes they encountered for the establishment of trade and commercial partnerships with the Indians. “In all your intercourse with the natives, treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will permit.”[21] Essentially, he thought, this would catapult the United States into becoming the world’s biggest player in the lucrative fur trade market. Jefferson told Congress the United States could undercut the British fur trade with China by using the Missouri, the Mississippi, and perhaps the Columbia River systems to get furs to China quicker than English companies. For commercial purposes, Lewis and Clark were, in a way, traveling salesmen, in addition to diplomats and army commanders.

The Corps of Discovery marked Jefferson’s fifth attempt to explore the West.[22] The expedition would not have been possible without the help of indigenous people including the 16- year-old Shoshone woman, Sacajawea. Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were the first white men to enter Idaho, Washington, and Oregon by land. On their way to the Pacific Coast, they camped across the Columbia on Wapato Island (near Portland, Oregon). It was not a pleasant experience for Clark, who wrote in his journal, “I slept but very little last night for the noise Kept up during the whole of the night by the swans, geese, white and great brant ducks on a small sand island they were immensely numerous and their noise horrid.”[23] The Corps neared the long-awaited shores of the Pacific on November 7, 1805. Clark rejoiced in his notebook, “Great joy in camp we are in view of the Ocian, this great Pacific Octean [sic] which we been so long anxious to see!” Evidently, they had not reached the ocean yet and mistook an estuary of the Columbia River for the Pacific.

When they arrived at the Pacific shore, they built Fort Clatsop and left discovery evidence in a document at the fort indicating American possession at the mouth of the Columbia River. They drafted it as a memorial or declaration of their presence in the Northwest. They also distributed the document to local chiefs of the region and instructed them to pass it out to any ship captains that arrived in the area. Lewis and Clark often recorded in their journals that they carved and branded their names on trees and stones along their journey. Clark’s name is still visible on Pompey’s Pillar near Billings, Montana. It is the only physical evidence left of the expedition on the landscape today. The success of the journey fired the imagination of scholars and ordinary citizens of the past and present.

The expedition would not have survived while they were living on the Oregon coast if it had not been for the efforts of the Chinooks and Clatsop who told them where the elk and other critical food supplies could be found. The Corps of Discovery had a Christmas dinner the day after the fort’s construction was finished. According to Clark’s journal, they ate “poor elk, spoiled fish and a few roots.” Lewis and Clark did not care for the Pacific Northwest climate at the mouth of the Columbia (today’s Astoria) during the winter months. During their four-month stay at Fort Clatsop, rain fell every day but for twelve days, and the skies remained cloudless for only six. They were excited to leave; if only they had arrived in July, then they may have found the area more appealing!

John Jacob Astor

Thomas Jefferson, in his pursuit to colonize the West, also encouraged American businessman John Jacob Astor to build a permanent fur trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River. Jefferson promised him all the support the executive branch could provide. Astor’s trading post was a significant foray towards American possession of the Pacific Northwest. There was political motivation among American lawmakers who thought England was intruding upon American sovereign rights of the Oregon territory. Fur markets continued to pull American commercial interests overland into the Louisiana Territory and toward the Oregon Territory. Following the footsteps of Lewis and Clark, Astor chased after dreams of wealth, prestige and power in pursuit of an Asian trade hub during the infancy of American globalization.

John Jacob Astor was a German immigrant and real estate magnate from New York City who amassed his wealth buying up foreclosed properties from small landowners. He was also a rent collector, but not for luxury homes; much of Astor’s estate in New York was covered with squalid immigrant tenements in disrepair. The maps of “Property in the City and County of New York Belonging to John Jacob Astor” as of April 1836 resembled a grand dominion with landholdings scattered across the New York metropolitan area.

In 1808, Astor expanded his prospective investments, and organized the American Fur Company, and by 1810, he established the Pacific Fur Company in the Oregon Territory in defiance of British claims in the area. Alexander Ross, an employee of the company, wrote in 1849 that the Pacific Fur Company was “an association which promised so much, and accomplished so little.”[24] From a business perspective, the Pacific Fur Company could be considered a failure, but from a geopolitical perspective, the establishment of Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River on the Oregon coast was a crucial gesture towards American possession. Astor supplied money to his venture enterprise and had American and Canadian associates operating in the field. They fanned out across the Northwest in search of business contacts to secure the fur trade. Astor negotiated a pact that made him the sole supplier of goods exported to Russian America, today’s Alaska, and he hoped to gain access to those fur markets as well.

Astor’s vision was to import blankets, cotton cloth, beads, brass kettles, metal tools, and weapons to outfit his men in the field and to trade with Native Americans. Indian men devoted more attention to hunting for furs, and native chiefs traded for copper with Euro-Americans. The fur trade led to the rapid depletion of the sea otter population to the brink of extinction during the nineteenth century. Astor’s vessels then carried furs to the markets of the Pearl River on the south coast of China to exchange them for cargoes of tea, porcelain tableware, silk cloth, furniture, fans, and other luxury goods for the residents of the East Coast of the United States. The ships returned to New York City to unload the imports and take on a new cargo of trade goods for the distant Oregon Country.

Astor dispatched an overland and a naval expedition to the north Pacific coast. Both of these expeditions would have their share of problems and disasters. Wilson Price Hunt was in charge of the overland party, he was one of the founding partners of the Pacific Fur Company, and completely inexperienced at leading an expedition. Along the way, Hunt lost part of his party composed of company officials and fifty employees, including the trappers John Day and Ramsay Crooks. Hunt and his party were met with troubles in the high plain of the Snake River in Idaho with no sign of water. His men were tormented by thirst, and some resorted to drinking their own urine and ate some of their animals. Hunt’s team eventually found the lost trapper near the Columbia River. Northern Paiute Indians stripped naked Day and Crooks and took all their belongings in retaliation for an Indian murder perpetrated by one of the company employees. They were left hungry with no resources to start a fire. The river near the site where the encounter took place would be named the John Day River by company employees. Day was traumatized by the experience spent the rest of his years in the Willamette Valley hunting for furs as a social recluse.

The marine component of Astor’s venture started in Boston aboard the Tonquin on September 8, 1811, under Lieutenant Jonathon Thorn. This choice proved one of the worst in a series of fatal miscalculations, and Thorn and his crew did not fare much better than Wilson Price Hunt’s expedition. The eight-month journey to Oregon was plagued by fighting and dysfunction among the crew because of Thorn’s horribly hot-tempered and unstable leadership. During the journey he stranded crew members at Tierra del Fuego and Easter Island, and he flogged crew members. Thorn’s cruelty cost eight men their lives at the mouth of the Columbia River when he ordered them out onto small boats to traverse the violent waters of the dangerous bar. He ordered his first mate, Ashton Fox, whom Thorn disliked, along with three inexperienced men and an elderly sailor out onto leaking boats. Fox objected, but the captain refused to listen to his entreaties. Thorn rebuked him, stating, “Mr. Fox if you are afraid of water, you should have remained at Boston.” Thorn was not to be deterred, and Fox turned to his partners and said, “My uncle was drowned here not many years ago, and now I am going to lay my bones with his. Farewell my friends, we will perhaps meet again in the next world.” Upon this, Fox had the boats lowered, and their small inadequate vessels were dwarfed by the waves on the turbulent waters at the mouth of the mighty river. The boat was submerged several times after traveling a few hundred yards, and the men cast up a distress flag. Thorn ignored it and ordered his men to continue upon their duties.

Alexander Ross recalled Thorn’s irascible leadership: “For the captain, in his frantic fits of passion, was capable of going any lengths, and would rather have destroyed the expedition, the ship, and everyone on board, than be thwarted in what he considered as ship discipline, or his nautical duties.”[25] Ross stated Fox met with the captain’s ire by trying to smooth over relations with the passengers on board the Tonquin whom the captain had mistreated and clerical employees he had treated as deck hands.[26] Thorn then ordered a second boat with five aboard to the sounds across the channel. It too capsized into the furious break waters. Of the unlucky crews, only two men—armorer Stephen Weekes and one of a dozen Hawaiians they had brought along—were later found alive near Baker Bay. Despite the challenges experienced by the crew, the Tonquin docked on the south bank of the river and there they established Fort Astoria in 1811. Governor Oswald West later in historical memory held an unflattering view of the crew of the Tonquin and in particular its French-Canadian crew members: “Company employees [of the Astor Pacific Fur Company] upon arrival on the Columbia, lost no time in giving the Indian maids the once over. When Louis, Baptist or Pierre spotted one to his liking he slipped a hunting knife to Papa, a string of blue beads to mama, and the deal was closed.”[27]

Later the Tonquin would leave Astoria. Thorn experienced perhaps a most deserving fate when he arrived at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. Transactions with the Nootka soured over when Thorn felt the Nootka were overcharging him on the price of otter pelts. Despite Astor’s instructions to Thorn and his crew to treat the Natives with fairness and kindness, Thorn kicked the furs back at the Nootka Indians and violently rubbed a headman’s face with a fur. His interpreter urged Thorn and his men to leave that night. Thorn refused, thinking he had taught the Indians a lesson. At dawn, canoes came alongside the Tonquin. The Nootkas who were seemingly unarmed, offered furs to trade, and Thorn allowed them on board. This was another instruction Thorn ignored from Astor. He had been advised to not allow trading on deck, or allow envoys to board the ship. Soon the deck swarmed with 200 villagers holding pelts. A call was given, and the Nootkas cast their pelts aside. They took out hidden maces and fell upon the crew. Thorn and most of the others were knifed or clubbed and thrown overboard where women in canoes finished them off. Only four of the Americans escaped, later to be caught and put to death. The next day, the Nootkas returned to the ship. A couple of the sailors were able to detonate a gun powder magazine blowing themselves up, along with several Nootkas. The Tonquin was destroyed, and the only survivor was an interpreter named Lamazee. After hearing the news of the ship and its crew, Astor went to the theater that night as a diversion. When an associate asked him how in good conscience he could shrug off the tragedy and entertain himself, Astor responded, “What should I do? Would you have me stay at home and weep for what I cannot help?”[28]

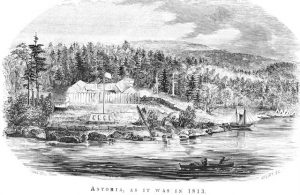

FORT ASTORIA: AMERICAN BEGINNINGS

Fort Astoria became the nucleus of Astoria, Oregon, the region’s oldest European American community. The outpost went through decades of trial and tribulation with its population dropping at times to a single family and a few employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company, but it endured. It was not as ideal as the Willamette Valley for settlement and a future “agrarian republic.” The Clatsop Plains lacked fertile soil and received far too much rain to reap the rewards of farming. But the Columbia River had great strategic importance, and the federal government spent heavily in its defense and kept its commercial channels safe and navigable with the establishment of lighthouses. Federal initiatives like these helped fuel the local economy and drew more Euro-American immigrants into the region. Astoria would become an important city on the Pacific coast, home to various ethnicities, but it was almost the city that did not happen.

Jefferson argued the United States owned the Oregon country because of Astoria, the permanent American trading post that John Jacob Astor had built. During the War of 1812, the British occupied Astoria and renamed it Fort George, giving the empire its first post on the North Pacific coast. Astor used his considerable political influence to lobby government officials to protect his post, even arguing that Thomas Jefferson, now out of office, had asked him to undertake the endeavor. He pleaded with James Madison to intercede at Fort Astoria for the good of the country. Most of the post’s disappointed leaders were prepared to sell the operation to the North West Company, a British fur trading conglomerate that rivaled the Hudson Bay Company, even before a British warship arrived late in 1813. The Treaty of Ghent in 1814 settled the war with Britain by restoring all the disputed territory in the Oregon region to the United States government allowing American companies to regain their access to the resources of Oregon. Americans and British merchants coexisted in Astoria until the Northwest Company was forced to merge with the Hudson Bay Company in 1821.

FORT VANCOUVER and JOHN McLOUGHLIN

In 1825, George Simpson, who worked in the administration of the Hudson Bay Company, relocated Fort George in Astoria to Fort Vancouver 100 miles downstream on the north bank of the Columbia River, across from what would become Portland, Oregon. He soon determined that the Columbia River fur trade “has been neglected, shamefully mismanaged and a scene of the most wasteful extravagance and the most unfortunate dissention.”[29] Simpson envisioned that fur traders would not rely on trading alone but would be kept busy and self-reliant by farming, fishing, or taking up some other profitable activity. Fort Vancouver would provide a crucial global trade link between China, North America, and Great Britain. Simpson made the Oregon country’s fur trade more centralized and profitable for the Hudson Bay Company.

The company created a credit system that served to tie Indigenous fur trappers and traders more closely to the company through debt. A similar system was deployed in the Ohio River Valley by Thomas Jefferson and the governor of Indiana, William Henry Harrison, whereby trading houses were vehicles of debt for Natives and they were compelled to cede their lands as payments for their outstanding debts. Along the coast, in areas that seemed more secure, Simpson favored a more sustainable trade in which the company relied largely on Native trappers. He appointed John McLoughlin, who had previously worked for the North West Company. He was a man of striking appearance both tall and regal with a penetrating gaze. The local Indians called him the White-Headed Eagle. As Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson Bay Company, he wielded great power. He headed the nerve center of a vast commercial system of various trade items and maintained an extraordinary presence in a remote frontier domain. Officially, he is known as the “Father of Oregon”.

Fort Vancouver was a small, self-sufficient European community, complete with a hospital and thirty to fifty employees of the company who lived with their Indian wives, like McLoughlin himself who married Marguerite Wadin McKay whose mother was Ojibwa. It was a cosmopolitan metropolis of sorts, with Indians, Hawaiians, métis, and French Canadians who were all links to the British imperial trade system. Many of the French Canadian settlers and employees of the fur companies had held Indian slaves, both male and female, as a slave could be had for ten to fifteen blankets. Most of them remained with their owners until 1855 and 1856, when they were rounded up by federal authorities and placed on Indian reservations. The French Canadian trappers—including Joseph Gervais and others, like Michael La Fromboise, who came in on the Tonquin—started the settlement in French Prairie. Gervais was born in Canada and died in French Prairie in 1861. He trapped fur for the both the North West and the Hudson Bay Companies, and he had several Indian wives through the years, including women from Chinook and Clatsop nations.

During the initial phases of Euro-American settlement and the opening of the fur trade, the Oregon Territory became a critical trade hub of globalization and American expansion. Many European powers contested for possession of Oregon, and gradually through trade and exploration, the region began to retain a multicultural hue.

[1] Calloway, Colin: First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, (Bedford St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2019) p. 218

[2] Belmessous, Saliha (ed.): Native Claims: Indigenous Law against Empire 1500-1920, (Oxford University Press, London, 2012) p. 20

[3] Miller, Robert: Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Manifest Destiny (University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 2008)

[4] J. Richard Nokes: Columbia’s River: The Voyages of Robert Gray, (Washington Historical Society Press: Tacoma, 1991) p. 67.

[5] Schwantes, Carlos: The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History, p. 20.

[6] Cook, James: The Voyages of Captain James Cook, Volume II (William Smith: London, 1842)

[7] John Ledyard, A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, and in Quest of a North-West Passage, between Asia & America

[8] Elliott, T.C., “The Strange Case of Jonathon Carver and the Name Oregon,” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Dec., 1920), pp. 341-368.

[9] J. Richard Nokes, p. xvi.

[10] Hayes, Derek. Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of exploration and Discovery. Sasquatch Books. 1999

[11] Historians argue the otter should have been the state animal of Oregon instead of the beaver.

[12] Nokes, Richard: Columbia’s River: The Voyages of Robert Gray, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma Wa. 1991, p. 194.

[13] Ibid. p. 185

[14] Nokes, Columbia River, p. 262

[15]Ibid., p. 195.

[16] “Thomas Jefferson to Andre Michaux, January 23, 1793,” Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress

[17] Schwantes, Carlos: Pacific Northwest History: an interpretive guide

[18] Mackenzie, Alexander: A General History of the Fur Trade from Canada to the Northwest, 1801.

[19] Thomas Jefferson to Congress, January 18th, 1803. Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress.

[20] Miller, Robert: Native America, Discovered and Conquered, p. 108.

[21] Jefferson’s Instructions to Meriwether Lewis, June 20th, 1803.

[22] In 1807 Sergeant Patrick Gass, who was a part of the Lewis and Clark expedition, used the name of Corps of Discovery in the title of his book about the expedition and it stuck. The actual nickname that is recorded in the Lewis and Clark journals is the “Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery.”

[23] Lansing, Jewel: Multnomah: The Tumultuous Story of Oregon’s Most Populous County, (Oregon State University Press: Corvallis, 2012) p. 9.

[24] Pyle, Robert Michael: “John Jacob Astor I: A Most Excellent Man?”, cited in Stephen Dow Beckham (ed.), Eminent Astorians, (Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, 2010)

[25] Ross, Alexander: Adventures of the First Settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River: A Narrative of the Expedition Fitted Out by John Jacob Astor, (Smith, Elder and Co.: London, 1849) p. 52-56.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Oswald West Papers Box 1 MSS 589

[28] Pyle, Robert Michael: “John Jacob Astor: A Most Excellent Man?” in Eminent Astorians, p. 70-71.

[29] Peterson del Mar, David, Oregon Promise, p. 85.