7 The Dawn of the Civil Rights Movement and the World Wars in Oregon

World War I: Americanization and Immigration

During World War I, Oregon had the highest enlistment rate in the country. Oregon also led the nation in per capita sales of war bonds. The state’s war effort produced remarkable economic development in shipbuilding, timber and agriculture. The Northwest experienced job growth and development in the industrial sector, and in extractive industries such as the timber industry. This growth was in part due to the mass mobilization of wartime production in areas such as airplane manufacture.

Since the United States allied with the Entente Powers during World War I, there was a great need for lumber exports to fulfill the insatiable need for airplanes in Britain, France, and Italy. The United States Congress created a Spruce Production Division of the U.S. Army, as part of the Aircraft Production Board under the Council of National Defense to meet the high demand for spruce, an ideal wood for building aircraft. The U.S. Army sent thousands of soldiers into the forest to cut timber, and a large number of civilian employees as well. Eventually there would be over 30,000 loggers, of which about 3,000 worked in Lincoln County on the Oregon Coast.

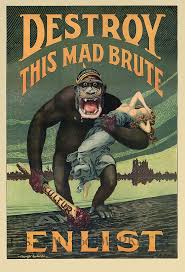

Government authorities and private interests whipped up war enthusiasm in the United States and racial hostility toward people of German descent. The ultrapatriotic feelings of the era were a by-product of jingoist saber-rattling of the media and government officials and assimilationist Americanization programs. The main crux of the argument among supporters of Americanization was for the necessary amalgamation of newly arrived immigrants into society according to specific cultural values. War production during World War I was partly incentivized by fanning the flames of racial hatred, “It is estimated there are around 3,000 soldiers in this county at the present time engaged in railroad building, logging and saw milling, but primarily all are working to increase the spruce production…When the Hun is licked, the work that is being done there now as a war measure will aid in the development and growth of our country.”[1] Americans slapped on the racial stereotype of the “Hun” to signify the German people as barbaric rapine baby killers who were a moral threat to American society.

Another factor that lead to Anti-German hysteria was a brewing nativist response to European immigration into the United States, and the ensuing Americanization movement. Pressure came from various states and the federal government to suppress “Germanism” which was perceived as a threat to American security. German identity was mistakenly associated with Communist Bolshevism and unbridled imperialism. City officials, responding to public demands, changed Germanic-sounding street names; and German Lutherans, Mennonites, and other German religious sects faced threats of injury and damage to their churches and property. The State Council of Defense for Oregon took no formal action against newspapers or speaking or teaching in German, but it did issue restrictions related to church services: “That the sermon shall be preached in English; all songs shall be sung in English; all Sunday school clases [sic] shall be conducted in English except a Bible class for old people who can not speak or understand English, may be conducted in the German language.”[2]

The American Protective League was a hyper-patriotic organization and a collection of 25,000 hacks or amateur spies that received tacit approval from the federal government and helped the Justice Department identify leftist radicals and ferret out German sympathizers. It was started by Chicago advertising executive A.M. Briggs. The League had a network of branches in 600 cities, conducted slack raids, opened mail, wire tapped phone conversations, and conducted raids on bookstores and newspapers. Government and media sponsored fear mongering and suppression had a harmful impact on German communities. In the census of 1920, there was a drop of about 25 percent of respondents who claimed they were of German descent. Concerns over American patriotism and a national desire to create unified support for the war effort, altered the social and cultural landscape and built increasing hostility and paranoia toward European and Asian immigrant populations and their cultures. Henry Ford and wealthy industrialists along with non-profits like the YMCA funded Americanization programs and created academic programs at American universities and colleges. Henry Ford, The Dupont and Harriman families all promoted what they called “the civilian side of national defense”. The University of Oregon started an Americanization department aimed at “perfecting plans for the Americanization and education of all immigrants in the State.” The intention of Americanization programs was for the United States to win the war overseas and creating a conformist patriotic home front in support of the war especially among newly arrived immigrants. An unfortunate by-product of Americanization vigor was a rise in nativist sympathies and distrust towards immigrant populations.

Early Tensions with Japanese Americans

The first generation of Japanese immigrants came to Oregon in the mid-1880s, following the Chinese Exclusion Act, to fill the resulting labor void from the absence of Chinese people. Many of the Japanese immigrants were single men who thought of themselves as sojourners who were in the U.S. to make their fortune and then return home. They would prove to be a perfect fit for the lumber industry. After the end of World War I, timber markets continued to thrive, and there was an increasing need for lumbermen.

The Pacific Spruce Corporation of Toledo, Oregon, hired twenty-five Japanese laborers at their lumber mill in 1925 for less than what it cost to hire white workers. Rosemary Schenck, the wife of Toledo City Marshal George Schenck, protested to a representative of the company, Dean Johnson, about the introduction of Japanese laborers into the town of Toledo. Johnson believed the Japanese workers were competently skilled for this work. Rosemary Schenck told an assembled crowd in Toledo that the Japanese were not wanted there and their presence would cause property values to go down. Frank Stevens, general manager at Pacific Spruce, explained that the Japanese laborers were not being brought in to replace current employees, but simply to meet a labor shortage. He insisted it was only a small crew of Japanese people and they would live in a segregated section of the town on mill property, which would be called the Tokyo Slough. “Not a single white man will lose his job. The Japs are not being brought in to take any one’s place, but simply to meet an emergency.”[3] The Tokyo Slough complex was built to house about sixty people. Employees living in the complex rarely came into contact with the local population, and they worked the graveyard shift. The complex was located next to the railroad track, and a communal outhouse was provided with multiple holes that dropped directly into the slough.

The Toledo Chamber of Commerce held a meeting to create a more restrictive declaration barring Japanese, Chinese, black, Hindu, and other “oriental” labor at the Pacific Spruce mill, but eventually the Businessman’s League no longer opposed the integration of Japanese labor since Toledo heavily relied on lumber exports. The chief of police and his wife, and a few business owners remained in opposition to Asian workers at the mill. They formed a nativist organization called, “The Lincoln County Protective League.” Their purpose was to “use all honorable means to protect our communities from the employment of Japanese and Chinese labor.” They delivered copies of a petition for the removal of the Japanese of Toledo to Governor Walter Pierce and the Japanese Council in Portland.

Things started to turn for the worse for the Japanese community in Toledo when a Japanese woman was told by the Chief of Police Schenck to leave town the next day or they would be thrown out or killed if they did not leave. Schenck denied this and stated “I warned the fellows to stay off the street for their own safety.” More speeches were organized by the Lincoln County Protective League and demonstrators were urged to action, “I appeal to every man who respects his flag to join the line.” The people of Toledo moved in for the attack on the Tokyo Slough housing development and chanted, “Down with the Japs,” “Out with the Japs,” and “Hang the Japs.”

Tamakichi Ogura later recalled in court in 1926, “They were pulling my shoulder and everywhere was a great noise, and I was falling down.” Ogura was horrified and stated to the deputy, “If we knew how unwelcome we would be…[and] if we had enough money, we would get out.” In all, twenty-two Japanese laborers, four Filipino employees, one Korean worker, two Japanese women, and three Japanese-American children were loaded into cars and trucks and taken to Corvallis. Following the riot, the Yaquina Bay News wrote, “Mob law resorted to and the Stars and Stripes desecrated is resented and deeply deplored by all law-abiding citizens.” The Oregon Voter also castigated the chief of police of Toledo for failing to perform his duties, which was “morally and legally indefensible.” The Great Northern Daily News, in an article on the “Japanese Expulsion Incident,” exposed what seemed to many a lack of due process of law. “We Japanese residents in the Pacific Rim and other regions have already been denied by law from working in agriculture [due to Alien Land Laws]. Now we are being denied the right to work in factories by intimidation. How will we make a living in the future if they limit how we live?”[4]

The Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants, hired by Pacific Spruce sued for damages, and the five lawsuits would establish a precedent for resident alien rights in the United States. The trial wasn’t held in Toledo since jury members were threatened with their lives if they indicted the accused, and the case was transferred to Portland. The jury awarded the plaintiffs $2,500 in damages, and the case established, for the first time in a federal civil suit, that foreign-born people living in the United States who were not citizens had civil rights that could not be violated by the will of local populations without consequences. In the end, the defendants were also required to pay the court costs.

Historian Eckard Toy indicated the trend among Pacific Coast states once regarded as progressive eventually “become less famous for reform than for repression…against religious, racial and political minorities.”[5] A general consensus grew in the region in deep opposition to “aliens” who could not be assimilated. White racists, some of whom were reformers and academics, on the West Coast played on fears of a “Japanese menace” that worsened and grew more apparent after the world war, and their hatred became institutionalized in the formation of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon.

Americanization, “Aliens”, and the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon

Professor F. J. Young at the University of Oregon was appointed the chair of the Americanization department in 1918, which was aimed at perfecting plans for the assimilation and education of all immigrants in Oregon. Americanization was a form of coercive patriotism that took root in the intelligentsia of Oregon and trickled into nativist ideology held by the Ku Klux Klan and spread among the popular masses. Frederick Dunn, the chair of the Latin Department at the University of Oregon, became the leader, or “Exalted Cyclops” of the large Eugene “klavern”. Eventually the Klan’s presence at the university would diminish as they were met with student inertia and faculty resistance, but many in the city embraced the racist tenets of the hate group.[6] The Klan had a prominent position in Eugene based on a historical past linked to Klan principles and ideology. During the Civil War era in Eugene, many sympathized with the Confederate cause, resisted against Reconstruction and the 14th and 15th Amendments, and the Eugene Herald and the Democratic Review were pro-South newspapers that opposed racial integration.

After World War I, there were mounting fears over the Red Scare and the perceived deterioration of moral standards during the early part of the modern age, with its purported excess in sexual profligacy and alcohol consumption. General economic troubles and runaway inflation created a ripe situation for the KKK to arrive on the political scene nationally, and in Oregon, with the mission of fixing the problems brought on by the modern age. The Klan zealously pursued a “morality crusade” in an effort to reverse the political and social gains of the Progressive era and to defend law and order, including the enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment (the prohibition of alcohol) with vigilante and coercive tactics.

The political atmosphere of Oregon during the post-war period was replete with patriotic and nativist sympathies, and receptive to Klan ideology. The Oregon Congress wanted to combat what they called “German and Bolshevik propaganda” and unanimously passed a bill restricting “aliens” from owning land and mandated English translations to be attached to any printed materials written in foreign languages.[7] Land ownership among Japanese people was a crusading point of contention for the Klan of Oregon. Governor Ben Olcott conducted an investigation of Oregonians’ opinion of Japanese land ownership, and it revealed “strong antipathy against the Japanese among small farmers, mechanics, laborers, and salaried classes in general. A large part of this antipathy is racial and does not depend on economic facts.”[8] The Oregon legislature was ripe for the political takeover led by nativism. Both political parties were influenced and shaped by the Klan whose power reached into the Oregon legislature and governorship.

Governor Walter Pierce harbored nativist sympathies and received support from the Ku Klux Klan. The extremist group achieved its peak popularity during the 1920s in the state. Many cities around Oregon developed Klaverns focused on Americanization, openly opposing Catholics and nonwhites, and spreading anti-Semitic hate speech. After the Oregon Congress passed Alien Land Law legislation in 1920, Governor Pierce signed the Oregon Alien Land Law in 1923, disallowing Chinese and Japanese nationals from buying and leasing land in Oregon, and banned them from operating farm machinery. The legislation was passed with the backing of the American Legion and the Oregon Grange, the farmer-populist social reform group that feared the possibility of Asian immigrants gaining a foothold in the agricultural sector. Chinatown and other Asian quarters in towns in Oregon were affected by anti-alien measures. Established Chinese and Japanese businesses were confronted with heavy regulatory and financial burdens due to the Alien Land Laws. Special monthly leases were written for Asian business owners that prevented alterations from being made by any merchant, building owner, or tenant. Anti-alien laws were contested by the Portland Chamber of Commerce, which contended there had not been an increase in that “type of population” in the state in recent years and that Asian people “constituted no menace.” The Portland Chamber felt there was no need to enact legislation that was an affront to the city’s Asian residents that “might prove detrimental to the interests of the port [and commerce].” In order to obtain a business license, Issei had to first appear before an examining board, which was the city council typically, in order to determine whether they were qualified to receive one. Issei were the only aliens who were required to go through this procedure. Alien land laws were passed in other western states like California, during the dizzying spell of anti-immigration animosity in the United States. After World War II, the United States Supreme Court barred alien land laws that prohibited Asian people from owning property as unconstitutional in 1952.

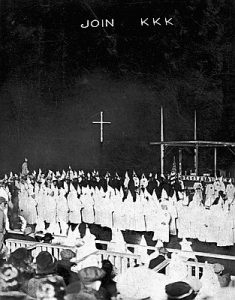

Klan organizers, sent from Atlanta, Georgia, did especially well in Oregon where they amassed a membership of 15,000. Maj. Luther I. Powell crossed the California border to start the Oregon Klan. In Southern Oregon, the town of Medford was the first to establish a klavern, or Klan chapter. “Kleagles” (Klan recruiters) from Texas and Louisiana fanned across the state, along the coast and into the Willamette Valley spreading their “moral crusade” of nativism and racial hysteria. Portland was the center of Klan activity west of the Rocky Mountains. Fred T. Gifford pushed Powell out of the state and became Grand Dragon of the Oregon Klan. The second formation of the Klan (the first started after the Civil War and was put to rest after the Congress’ Enforcement Acts) confined membership to white native-born Protestant males. Historian Stanley Coben described the Klan of the 1920s as “guardians of Victorianism.” The appellation addressed the other aspect of their moral crusade, the enforcement of Prohibition laws and policing of prostitution and sexual mores.

Klansmen, like Gifford, supported what they called “100 percent Americans” and opposed “hyphenated Americans”, especially people from Southern and Eastern Europe. Gifford insisted that their Americanization was the only solution, [these] “mongrel hordes must be Americanized, failing that, deportation is the only remedy.” The Klan’s racism was born among a paranoia among small-town Protestants against Bolsheviks (including any radicals like labor organizers), Irish-Catholics, Eastern Europeans, Jewish people and southern Europeans who arrived into America around the turn of the century.[9]

Lem Devers, the editor of the Portland-based Klan newspaper the Western American, echoed the sentiments of state politicians and felt materials printed in foreign languages was antithetical to “100% Americanism,”

“Americanize the aliens, winning their high regard for true patriotism, by precept and example. Somehow must be assimilated the several groups which now wrangle their foreign jargon in preference to English, and who mistakenly keep aloof from American affairs…thousands remain who regard America as merely a land of refuge and place for money making. The best way to Americanize all foreigners is to develop leadership among their own people thus to make all understand our institutions of liberty and their individual rights under the Starry Flag-especially teaching them that foreign rights end where American rights begin that the native born, bona fide, unhyphenated Americans are determined never to abdicate rule to their adopted brothers.”[10]

The Klan’s 100% Americanism was based on Protestant ideals, and drew converts from ministers of the Protestant faith. An Astorian clergyman praised the organization, “I can merely say that I have a deep feeling in my heart for the Klansmen… and that I am proud that men of the type these have proven themselves to be are in an organized effort to perpetuate true Americanism.” Rev. Reuben Sawyer of Portland spoke before a crowd at the Portland Auditorium November 18th, 1922, “I pledge my time, my influence, my vote and every honorable means at my disposal in forwarding the great work of keeping America a white man’s country founded by our Pilgrim fathers who were noble representatives of that imperial white race entrusted by Almighty God with the solemn mission of bringing forth a nation that should be the means of blessing all the families of the earth.”[11] Protestant clergy looked to the Klan as protectors of tradition and valiant men of action and gallantry. Some ministers of faith helped spread their gospel of white supremacy while many other religious leaders outside their tribal circle rejected it.

The Klan found fertile ground in Oregon whose population in 1920 was 85 percent white, native-born, and 90 percent Protestant. During its growth into statehood, Oregon drew migrants from a monochromatic ethnic base that saw themselves as the chosen people in a promised land. The Klan reinforced white nationalism, and Protestant resistance to the Catholic church and parochial schools. Gifford seized upon the political demographics and recruited Klansmen from across the state. Klaverns surfaced everywhere in towns like Astoria, Sherwood, McMinnville, Gladstone, Lebanon, Dallas, Albany, Eugene, La Grande, Jacksonville and Salem. There were also klan representatives in Roseburg and Marshfield (today’s Coos Bay). Klaverns also appeared in The Dalles, Condon, Pendleton, and Baker.

The Klan was connected to law enforcement in Portland and other cities. They directed their moral crusade towards Prohibition and the removal of bootleggers who were associated with immigrants. The Portland Police gained Klan recruits within its membership, and they harbored nativist sentiment toward immigrant populations. In 1923, Police Chief Lee V. Jenkins claimed that crime related to prohibition came from the “inability of America to assimilate and Americanize the huge horde of immigrants that have come into the country.”[12] The Oregonian wrote alarmingly that “men from all walks of life” were among the two thousand inducted into the Portland Klan including lawyers, doctors, businessmen and Protestant clergy. The Portland branch of the NAACP took notice of the rise of the Portland Klan in 1921 and wrote to Governor Ben Olcott about their concerns. The telegram protested against Klan parades in Portland. “We humbly pray your honor to prevent in our State any organization to public demonstration of the said notorious (KKK) under any pretext whatsoever.”

Fred Gifford and the Portland Klan planned a political takeover and wanted to override the Oregon System. Gifford tried to create a Good Government League and held a convention. He urged Klansmen throughout the state to propose slates of officers for mayor, constable, city and port and county commissioners, as well as candidates for senate and the house. The Klan’s efforts to eradicate the Progressive’s Oregon System and replace it with a racist hooded Americanism based on elite authority, misfired and came up flat in Portland.[13]

The city of Astoria felt the impact of the Klan in the 1920’s as well. Astoria’s immigrant population was Oregon’s highest, with 60 percent of the population of some 14,000 having at least one parent who was foreign born. The Klan’s promise to corral “alien” forces struck a chord in the city. Before the Klan faded by 1928, more than two thousand citizens of Astoria had joined. The KKK gained support through their beneficent support of community causes, often through Protestant churches. They capitalized on secrecy and hierarchy, and used tools such as boycotts and propaganda to apply pressure on those who would not yield to their demands. They made charitable contributions with grand entrances and flourishes. They successfully replaced the county sheriff, and through charity donations, won the support of hundreds of church-going, middle and upper class, white, Protestant Astorians.

The Western American newspaper updated its readers on the crusade to enforce the 18th Amendment’s prohibition of alcohol. It voiced its enthusiasm for Klan leaders like the Sheriff of Astoria, Harley J. Slusher. The Western American captured the attention of readers with sensationalized accounts of Klan members in positions of power like Slusher, “Already with less than four month’s experience in office, the Sheriff has cleaned out a number of dens in Astoria and brought some stills that never had been bothered.” Slusher wanted to fulfill the campaign promises he made to his supporters when he declared, “I made the people some pledges before the election, and I am going to carry them out. Law and Order have come to Clatsop County to stay.”[14] Sheriff Slusher cracked down on rooming house proprietors by curbing prostitution in Astoria. “Local booze vendors” were shut down in Gearhart where 100 gallons of grain mash, moonshine and beer were found in a Finnish bath house.

Merle Chessman, the editor of the Astoria Evening Budget, denounced the Klan’s political agenda and its iron hand approach to Americanization. After the Klan purged Catholics from the Chamber of Commerce and the local school board, Chessman wrote, “Carry On Knights of the Ku Klux Klan! Carry on until you have made it impossible for citizens of foreign birth, of Jewish blood or of Catholic faith to serve their community or their country in any capacity, save as taxpayers.”[15] His words infuriated the Klan and its supporters. They wanted Chessman fired and even tried to purchase the Astoria Evening Budget. The Klan stated Chessman and his newspaper were not “on the list of our friends” for its almost daily malicious “faslehoods” about their organization. The Klan won the election of key positions in Astoria’s governmental bureaucracy under the spell of communist hysteria and anti-immigration nativism. The Klan’s impact in Astoria was short-lived, and after a few years the Klan lost its political power as it had throughout the state. With the presence of a large diverse immigrant community in the local labor force in canneries and the timber industry, Astoria’s citizens could not afford to alienate their foreign population who brought revenue to the region with their hard work.

According to the historian Jeff LaLande, the Klan had significant presence in Jackson County in Southern Oregon. Medford was the first Oregon outpost of the Ku Klux Klan, and they began an aggressive membership drive in Jackson County. It was ethnically and religiously homogenous and the Klan found populist appeal where a prohibitionist battle with bootleggers unfolded. The town of Medford had transformed into a railroad town connected to national markets; it was the metropolis of southern Oregon. Membership in the Klan rose quietly to include wealthy urban residents, professionals and businessmen. What bound them together was nativism, moral concerns and economic bitterness. The Medford Clarion was the mouthpiece of the Klan which harbored Anti-Semitic writings from Henry Ford’s Dearborn Independent, and pieces espousing anti-Catholicism particularly targeting the Catholic Church as holding absolutist authority in American politics. Medford mayor Charles E. “Pop” Gates, who owned the largest Ford dealership in southern Oregon, accepted honorary membership in the Klan. After his induction ceremony, he felt like a changed man and thought the Klan may be beneficial to the people, “the oath was one that no Christian man could take exception to…If a man is not a better citizen after…he is not a fit subject for any order or community.”[16]

Union County in northeast Oregon was another epicenter of Klan law and order. The city of La Grande was second to Portland in population size and economic importance. It was the commercial hub and highway construction headquarters of eastern Oregon. It historically has served as a distribution and processing center for livestock and agricultural commodities. The presence of the Oregon-Washington Railroad and Navigation Company stimulated rapid urbanization and an influx of Chinese and African American people to La Grande. Citizens and newspapers grew concerned over vice and crime in the city, and saw opium and alcohol use as social problems brought on by immigrants into the community. “When a Chinaman steps out and induces Americans to smoke opium or use dope, way goes patience of real Americans who have permitted these descendants of Old Confucius to live under the stars and stripes.”[17] Drunkenness at town dances “has to be stopped” Municipal Court Judge R.J. Kitchen declared in 1923. Klan membership surged in La Grande, but never reached the required amount of one thousand initiates in order to receive permanent charter status.

The significance of the La Grande Klan was its connection to the election of Democrat Walter M. Pierce to the governorship of Oregon. Pierce appeared before the La Grande Provisional Klan and gave his thanks for the support of all “100% Americans” in the recent election. Granted, both parties were influenced by the Ku Klux Klan with the Republican Party fielding its Klan candidates. Pierce held undeniable appeal as a populist in favor of tax reduction and a campaign built on the message, “throw the bums out.” The secretary of the La Grande klavern noted how the Klan intended to work closely with the newly elected governor coordinating the work of a previously held ambition of Oregon Grand Dragon Fred Gifford’s Good Government League. Together the Klan and Pierce were posed to select government officials built upon Klan principles and Americanism:

“Governor Pierce told Mr. Gifford that all appointments he made would be given to men who are wright (sic) owing to the fact…[and] he shall take his list of appointments to Gifford’s office and together they will go over the list and weed out the culls. Gov. Pierce and the Klan are on trial and by our Loyalty to him and are (sic) efforts to keep out all Bolshevism we will succeed…Governor Pierce’s success means our success…get behind this administration and lets give the people of the state of Oregon something in the line of true Americanism that they have never had presented before.”[18]

The Klan secretary of La Grande reflected on their continuous support of the upcoming governor, “Let us bid Klansman Pierce [emphasis added] God’s speed in his new undertakings, as we have done in the past.”[19] Governor Pierce relationship with the Klan was reciprocal, and he was seen as one of their own.

Governor Pierce, with strong support from the Klan, backed the anti-Catholic Oregon Compulsory Education Act, which banned private and parochial school education in Oregon. The bill was intended as a means of eradicating the influence of the Catholic Church in American society. The Oregon Klan’s position on the Catholic Church was shrouded in terms of a religious war or crusade, “We must ever consider ourselves engaged in a battle until we or those who behold the downfall of Catholicism buried in the ruins of its own iniquity.” A state committee on alcohol trafficking had proposed a bill that would have prohibited the transportation and use of sacramental wine during the same time, which also received strong Klan support and backing. The Oregon compulsory public school initiative of 1922 provided a boon to Klan popularity. The measure proposed to require children to attend public schools instead or private, parochial or military academies. It was an effort to support “100 Americanism”, and using public education to teach fundamental national values to all children. Sponsors of the bill were the Klan and the Federation of Patriotic Societies.

The long legal battle to repeal the law was led by civil rights activists in Father Edwin Vincent O’Hara and Rabbi Jonah Wise of the Temple Beth Israel in Portland. Oregon voters approved the compulsory public school law, but the Oregon Supreme Court in an unanimous ruling declared it unconstitutional, and that decision was upheld by the U. S. Supreme Court in Pierce vs. Society of Sisters, in 1925. The justices voting in the majority stated private schools are protected by the constitution and that parents’ have an inherent right to freedom of choice in their children’s education. Lutherans, Seventh Day Adventists, Episcopalians, and the American Jewish Committee were opposed to the measure and provided legal support to have the law declared unconstitutional. In the aftermath of the compulsory public school law, the Catholic Church of Oregon created a Catholic Civic Rights Association to defend against attacks on religious freedoms in Oregon.

CIVIL RIGHTS REFORM IN OREGON’S AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY

Oregon statehood was forged through racial exclusivity in its constitutional laws. Black citizenship was criminalized. While exclusion laws were rarely enforced, they remained in place until 1926 and had a tremendous impact on the urban and social landscape. The ban on racial intermarriage of 1866, and the poll tax implemented in the state constitution against people of color were two effective means by which an alienated and marginalized population was created through state laws. But a different historical force was going to reshape the demographic composition of the state: the Great Migration.

After the Civil War, the United States federal government implemented a political and social realignment reform package called Reconstruction. This opened up the vote to African American men, enshrined equal protections in law, but more radically, put men of color in elected positions, promoted mass literacy, and the removal of many of the social hallmarks of slavery in the American South. Reconstruction was met with violent tenacious resistance from white politicians of the South, and the erosion of Reconstruction policies and protections was nearly complete by the time of the Supreme Court ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson which legalized racial segregation and reinforced racial blood laws from the antebellum era of slavery. Conditions quickly worsened for African Americans in the South, and many Americans experienced a loss of faith and interest in fighting for Reconstruction in the South including President Ulysses S. Grant.

With little viable alternative options, African Americans left the south in droves. The large scale migration impacted Western states and cities in the Midwest. When the railroads expanded within Oregon’s interior, the agricultural sector opened up to national markets, and workers were needed to fill positions to help transport people and commerce. African Americans were limited by racial discrimination in employment opportunities, but there were jobs available in the railroad industry and menial labor. As job opportunities in the railroad and hospitality industries opened up, Multnomah County experienced a surge in African-American migrants. Black people were not permitted to eat in white-owned restaurants, so black-owned restaurants and saloons were able to provide a service to the black community and to the railroad men away from home. Employment opportunities for black people in private industry and government were largely limited to jobs as service personnel in hotels, restaurants, and in office buildings as janitors, doormen, porters, bellhops, waiters, and cooks.

While many African Americans arrived in Western states like Oregon during the Great Migration, legal reforms were needed to provide protections for all people in the state. In the 1890s black leaders and their white allies initiated legislative efforts to remove the poll tax measures, exclusion laws and bans on interracial marriage. Some of the leaders of legislative reform were in African American churches. Reverend T. Brown, pastor of the African Methodist Episcopalian Church of Portland (the oldest African American church in Oregon), concerted efforts with Oregon State Representative Henry Northrup, to abolish the exclusion laws that permitted the removal of African American and Chinese residents from the state. The legislative fight came up short, and an Equal Rights Bill failed to pass the Oregon Senate in 1919. That same year the Portland Realty Board added to its code of ethics a redlining provision, prohibited realtors from selling property in white neighborhoods to African Americans and people of Asian descent because they believed their presence in neighborhoods brought down the value of neighboring homes. This established a legacy of housing segregation that rippled throughout America and was instituted in residential development policies by the United States Housing Authority through the 1970s.

BEATRICE MORROW CANNADY: CIVIL RIGHTS ADVOCATE

Adolphus D. Griffin was a successful businessman and the publisher of The New Age, and was the first black-owned newspaper in Oregon in 1896. It wasn’t designed to appeal to a strictly black audience, giving it a wider appeal. Portland’s second black-owned newspaper, The Advocate, began publication in 1903, and Beatrice Morrow Cannady eventually became its editor. It was the state’s largest African American newspaper. She was the first African American woman to graduate from the Northwest College of Law in Portland. Cannady was a founding member of the Portland branch of the NAACP and served as its secretary and vice president. The branch was the first NAACP office to open west of the Mississippi River in 1914. She was also the first African American to run for political office in 1932 as a state representative from Multnomah County. She was a pioneer for racial justice and a critical activist in the budding civil rights movement in Oregon. As an attorney, she single-handedly fought segregation, the Klan and racial injustice in Oregon, and established a name for herself with Congressional leaders in the federal government like Leonidas Dyer.

Portland Mayor George Baker had requested that the city attorney draft an ordinance making it a crime for African-Americans and whites to mingle in dance halls and restaurants. Cannady and the NAACP of Portland fought against the city ordinance, calling it an act of “deep humiliation.” The black community objected to the passage of an ordinance prohibiting racial intermingling because it would set a precedent for discrimination already practiced in theaters and restaurants, and might lead to widespread segregationist policies in transportation and education. Cannady used The Advocate to expose racial discrimination and those who enabled it. She particularly criticized Mayor Baker’s comment on the “intermingling of races” in public accommodations. In response to Mayor Baker’s embrace of racial discrimination, Cannady suggested black people boycott eating establishments and other businesses that had refused service to black people.

Cannady and the NAACP protested against the showing of the film The Birth of a Nation in Portland movie theaters. D.W. Griffith’s sensationalist racist movie glorified the Klan as moral crusaders and reinforced pernicious stereotypes of African American men as rapine, bestial, incompetent and prone to alcoholism. In the film, the Klansmen are portrayed as guardians of white women’s chastity, and sexual interactions between black men and white women are anathematized. President Woodrow Wilson unfortunately celebrated the film and claimed it was “teaching history with lightning,” in a conversation with the film’s director. The movie was based off the novel The Clansman written by the white supremacist Thomas Dixon Jr. who as an old college friend of Wilson when they attended Johns Hopkins University. Wilson never condemned the film, and this only added to his reputation for being an ardent racist who denied black students admission to Princeton University while he was president of the college, and allowed most cabinet members to segregate federal workspaces for the first time since the Civil War.[20] The popular reception of the film exacerbated racial divisions in Oregon and the United States. The film normalized the Klan and encouraged recruitment into the terrorist organization.

In 1916, The Birth of a Nation was scheduled to be shown in Portland, and a group associated with the NAACP , including Cannady, appeared before the city council to protest the film. Caught by surprise from the protest, the council reacted by passing an ordinance that would ban the showing of any film that would stir up hatred between the races. In 1931, the American Legion sponsored a showing of it, and a percentage of profits were intended for their charity work. Cannady and the NAACP were able to block this showing as well. The Triangle Film Company appealed to the City Council of Portland to show the film, and it became the fourth time the council had refused a permit for the film. It was largely Cannady’s efforts that blocked the exhibition of the film. Part of her motivation stemmed from experiencing first-hand discrimination at the Oriental Theater in Portland. An usher tried to prevent her from sitting on the main floor with her son, and claimed the seats were for white patrons only, but Cannady refused stating she was a law-abiding citizen who paid for her tickets. Later, she had discrimination lines in theaters banned in Portland. In another incident, Cannady’s son George was prevented from entering a skating rink to attend a graduation party with his friends. Soon after this humiliating incident, she was able to work towards the removal of “we cater to white only” signs in the city. She felt segregation was the root of all evil “for when people do not know one another they are suspicious and distrustful to one another.”

Cannady’s direct action against school segregation had an impact in the town of Vernonia in 1925. During this time, racial segregation was experienced in schools in Mayville near La Grande, and Catholic schools in Portland. Vernonia was a village of 1,000 people supported by a sawmill run by the Oregon-American Lumber Company. They drew some of its employees from the black community of Oregon and another fifty African-American employees from its properties in Louisiana. Living conditions on company property in Vernonia were established under Jim Crow policies of residential housing: superior accommodations for the whites and inferior ones for the people of color. For the white workers, the company provided houses in a good district with paved streets and sidewalks with modern conveniences in homes. The African-American employees lived in shacks of two or three rooms built at the bottom of the hills. There was inadequate drainage, no paved streets or sidewalks, one water tap to be shared by two or three homes, and subpar sewage systems. The African-American employees were also underpaid in comparison to white laborers for the same work. One of the employees of the mill wrote to the NAACP to alert them to the situation. “Please do not let no one know who wrote to you about this.”[21]

The environment was becoming increasingly hostile when the lumber-company-owned local newspaper the Vernonia Eagle printed an editorial in 1925 stating the town did not want “niggers” in Vernonia, and that it was a “white man’s country.” Five children were prohibited from attending school and were told to go to school in Portland thirty-five miles away. The owners of the mill shared similar racist sympathies as the newspaper, blocking the children of color from attending the public school in Vernonia. An African-American employee of the sawmill refused to comply with the segregation orders, and the lumber company fired him for sending his child to the town’s public school. The superintendent of the company stated that if anyone sent their children to the public school, they would be fired. The school board and “patrons of the school” accepted the conditions of segregation.

Cannady summarized the situation in Vernonia upon her visit: “The whole thing in a nutshell is an attempt to duplicate the Southern system here. We will not stand for it.”[22] Cannady claimed the company was in violation of federal laws granting equal protection, “We have laws that cover the situation…[in a] state where the whole sentiment is Southern.” Cannady spoke personally to town and company officials to change their policies, and ensured that African American students were able to attend the public school in Vernonia. Cannady also helped set up a branch of the NAACP in Vernonia, and was victorious over segregationist practices at a public school in Longview, Washington.

Cannady gave many speeches on the subject of interracial relations in schools, colleges, clubs and many other organizations. She was a guest lecturer at the Pacific College of Newberg ( currently George Fox University), and persuaded the Portland Board of Education to offer courses on African American history to the city’s high school students. Cannady was active in political circles and invited Congressman Leonidas Dyer to speak at Lincoln High School. Congressman Dyer tried to pass federal legislation that made lynching of African Americans a federal crime.[23] The Dyer Bill was very important legislation for Cannady and the black community. The Advocate ran front page articles on lynching incidents in the United States, and brought attention to a pressing issue that demanded federal action for equal protection. After her speech and presentation at Lincoln High School, students wrote letters to Cannady thank and praising her. One Lincoln High student noticed how the media inflamed racial hysteria and the issue of urban crime, “When a negro commits a crime, much more attention is given to it.” When Cannady spoke at the Daily Vacation Bible School in Portland, her lecture became a “mass conversion experience” for many, including a former Klansman. Cannady raised awareness in the community on her lecture tours, and through her activist work. She was very warm and personable, and invited guests of different backgrounds into her home where conversations on unity and social awareness were welcomed and embraced.

After the Broadway Bridge opened in Portland in 1913, the city’s black community moved east across the Willamette River to the Albina District in Northeast Portland along Williams Avenue. By the 1930s, Williams Avenue and the Albina District, slowly became a black neighborhood and a product of racial segregation. The area became a thriving center of black culture with African American owned businesses, churches, and community centers. The YWCA on Williams Avenue was referred to as the “Colored YWCA” in the organization’s efforts to provide services to the growing African American community. The Albina District was a convenient location for the black community enabling commuters access to streetcar lines that took them to Union Station and other job sites in downtown Portland. Racially restrictive covenants were instilled in housing districts throughout Portland evidenced by a Laurelhurst deed that forbade any Chinese, Japanese or African American from residing in the home as except as domestic servants. However the Albina District represented a place where black people could own a home without facing as much resistance as they had in other locations in the city. Dr. DeNorval Unthank’s family decided to test the waters and tried to set up residence out of the Albina neighborhood.

Dr. DeNorval Unthank received his medical degree from Howard University in 1926, and was recruited by the Union Pacific Railroad and Dr. James A. Merriman to come to Portland, Oregon. They were the only black physicians in town and were brought on to serve the black employees of the railroad company. Unthank was a civil rights pioneer in Oregon history. His painful experiences with discrimination brought him closer to political activism. He served as president of the Portland branch of the NAACP, co-founded the Urban League, exposed residential segregation as one of the only African Americans in the Portland City Club and helped push for the passing of Oregon’s Civil Rights Bill in 1953.

Dr. Unthank’s family attempted to move into Ladd’s Addition, an all-white neighborhood in Southeast Portland in 1931. Upon their arrival, a neighborhood club called the Better Homes Group objected to their new neighbors. The Unthanks were presented with petitions demanding their departure. The Better Homes Group told the Unthanks they should not be concerning themselves over segregation, and should focus on their own self-improvement instead. They claimed the African American social reformer Booker T. Washington, wouldn’t have moved into a white neighborhood. When the Unthanks refused to leave they were verbally threatened and vandals broke 18 windows of their home, and left trash and a dead cat on their lawn. The neighborhood sought litigation to force the Unthanks out of the neighborhood. The following year, Ms. Ida Tindall, an African American widow and a Gold Star mother of a World War I veteran, bought a home near Ladd’s Addition in Portland and was met with white resistance. Another neighborhood group and a realty firm called The Rose City Company sued her and tried to evict her from the neighborhood. The NAACP took an interest in her case and hired Charles Robison as her attorney. Beatrice Morrow Cannady and The Advocate printed a poem called Black Star Mother written by Robison “They took this woman’s money and now they won’t give her a home…They tell me about Gold Star Mother-I am speaking about a Black Star Mother of a man who fought for his country when his hide was black.” Jewish organizations and the NAACP supported Robison’s efforts to bring awareness to housing discrimination in Oregon.

The NAACP contested segregationist practices and policies through the 1930s, and they built upon their efforts to get a civil rights bill passed in the Oregon State Constitution. Beatrice Morrow Cannady and The Advocate warned readers of the reality of residential segregation in the city of Portland and felt the Albina neighborhood was evidence of racial discrimination. Oregon voters and the city of Portland rejected New Deal funding for public housing. This left African Americans few housing choices, often leasing out to landlords who neglected their properties and overcharged tenants for rent. Dr. Unthank and the NAACP brought awareness to housing discrimination in Portland and went on letter-writing campaigns, called for community meetings, and staged protests at the capitol in Salem.[1]They pushed for a civil rights bill that would have provided protections from housing discrimination, but it died in committee due to opposition from the Oregon Apartment Owners Association. By 1940, 60 percent of Portland’s African American population lived in the Albina neighborhood while the problem of segregation and racism festered in Oregon.

Political Radicalism in Oregon

Political radicalism and labor reform became prominent forces of potential unrest and civil disorder in the eyes of government officials in Oregon. In the wake of the Red Scare hysteria and the fear of communism, the state passed a Criminal Syndicalism Act in 1930 which forbade speech that was viewed as “subversive”, or posed a “clear and present danger” to American society and its institutions. The law was designed to suppress radical unions like the International Workers of the World, and communists and socialists. The Criminal Syndicalism Law of Oregon gave governing authorities the power to infiltrate, monitor and disrupt leftist groups perceived as subversive and a threat to society. The Portland Police started a covert operations group called the Red Squad that was financed by taxpayer dollars and employers who wanted to ferret out communism among their employees. The police group was founded upon the idea that “Communism was the source of all woe,” and radical leftist groups sought the overthrow of the American government.

One person prosecuted by the Criminal Syndicalism Act was Ben Boloff, a Russian laborer who was arrested in 1930 on charges of vagrancy, but police found he was carrying a Communist Party membership card and his charges were changed to “criminal syndicalism.” The Oregon criminal syndicalism statute barred a person from being a member of Communist party. At the trial, officers in the “Red Squad” testified against Boloff. He was the first to be tried under Oregon’s Criminal Syndicalism law and was found guilty. The judge sentenced him to ten years in the penitentiary. His attorney, Irvin Goodman, was a member of the International Labor Defense which was the legal arm of the American Community party. He appealed Boloff’s conviction to the Oregon Supreme Court but the justices affirmed the ruling. Many considered the Boloff conviction a travesty of justice.[2] The Oregonian and the Oregon Journal sided with Boloff. While in prison, he contracted tuberculosis under poor living conditions, and was refused medical attention. He was eventually released from jail but died soon thereafter. Supporters of Boloff thought the state should have been prosecuted for his wrongful death.

Dirk Dejonge was also convicted under the Criminal Syndicalism Law for participating in a meeting bringing awareness about jail conditions at Multnomah County and the Longshoremen’s Strike of 1934. Irvin Goodman of the ILD and Portland attorney Gus Solomon, who helped establish the first American Civil Liberties Union office in Portland, represented Dejonge during his appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court. After the Oregon Court denied a rehearing for Dejonge, the case found its way to the United States Supreme Court and Solomon found Dejonge legal representation in Osmond Fraenkel of the ACLU. In an unanimous decision, the Oregon Criminal Syndicalism law was declared unconstitutional and Dejonge’s right to freedom of speech and assembly had been denied by the Oregon courts. Later in his career, Attorney Solomon learned he was labelled a communist by the “Red Squad” of the Portland Police Bureau and the ACLU was also listed a communist organization.

The Criminal Syndicalism Act created an atmosphere of Red Hysteria that enveloped other criminal cases, and led to hostility directed at unions and radicalism. In 1932 at Klamath Falls, a murder investigation of a dining car steward on the Southern Pacific Railroad became a cause célebre for the International Labor Defense and Attorney Goodman who represented the accused, an African American waiter named Theodore Jordan. Initially Jordan went to the NAACP to seek legal support and it was revealed he was subjected to third degree torture while in police custody. Cannady and The Advocate followed the case closely. The newspaper and the International Labor Defense brought attention to the case by comparing it to a legal lynching because Jordan was sentenced to death for a crime that he did not commit, and was forced to sign a confession while under physical duress.

Jordan grew impatient with his legal defense and sought representation with Portland Attorney Irvin Goodman and the communist-aligned International Labor Defense. The ILD gained notoriety for successfully defending the Scottsboro Boys who were nine African American men wrongfully accused of raping two homeless white women on a train. When the NAACP caught wind of his solicitation of the ILD, they severed all ties with him, but not before an argument broke out among African American social activists and public figures who sided with the ILD and members of the NAACP at Mt. Olivet Baptist Church in Portland. The Portland branch of the NAACP was extremely nervous about being associated with the ILD and communism. Eventually after repeated efforts by the ILD and public protests in Portland and the Capitol Building in Salem, Jordan had his death sentence commuted by Governor Julius Meier after an investigation by a legal redress committee concluded that Jordan’s rights had been violated. Unfortunately Jordan remained in jail for several decades until the real murder’s identity was revealed. In 1964, Klamath Falls Justice David Vandenburg threw Jordan’s sentencing out of court because the nature of the trial was repugnant to constitutional law and Jordan’s right to a fair trial, and it was not until then that Jordan was finally released from jail for a crime he did not commit.

Oregon Enters World War II: Hydroelectric power and the New Deal

During World War II, the Pacific Northwest became a thriving center of job growth and an ensuing population explosion from war industries like Boeing Airplane in Washington, and the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation in Portland. The stock market crash of 1929 and the preceding Great Depression devastated the industrial sector of the U.S. and other nations. After years of economic depression, the United States and Germany employed the economic model of British economist John Maynard Keynes. His theories were premised on government expenditures to fund economic growth, agriculture and industries were subsidized, but at a much higher scale than previously seen. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called this economic plan the New Deal, and it emphasized state spending for production and infrastructural development which yielded job growth and professional training of workers. As World War II unfolded, the United States and German governments funneled millions of dollars into the mass mobilization of war production. Federal spending skyrocketed in a short period of time as the military sector required enormous production of equipment. This required consumer production in factories such as Ford Motor Company to shift its assembly lines to war preparedness. Tanks, jeeps, and other essential military equipment replaced cars and other nonessentials in the consumer market during the war effort. In the Pacific Northwest, massive job growth occurred in Boeing Airplane Company and the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in 1941, the United States entered the alliance against the Axis Powers of Nazi Germany, Japan and Italy. American went under high alert against the possible threat of a Japanese invasion on the Pacific Coast which never materialized.[3] American wartime production was exported to other allied nations such as Great Britain, China, the exiled government of France, and the Soviet Union. This massive economic growth pulled the United States out of the Great Depression. The Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation had three shipyards in the Portland metropolitan area. The Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation was run by the industrial magnate, Henry Kaiser, who was also the founder of Kaiser Permanente which met the healthcare needs of tens of thousands of his employees in California, Washington and Oregon.

Kaiser’s military industries were one of the primary causes of the vast emigration to the state of Oregon during the Second World War. Kaiser shipyards brought African Americans into Portland and Native Americans left the reservations to work there as well. The influx of prospective employees into Kaiser’s shipyards led to further ethnic diversification, and the population of Oregon increased 49 percent during the war which led the nation. But the housing market did not have enough space for these new residents. The war production of Boeing and Kaiser Shipyards would not have been possible without inexpensive electricity provided by the dams built along the Columbia River through government spending for infrastructural development in Roosevelt’s New Deal.

One of the extensive undertakings of the New Deal was public infrastructure projects like hydroelectric power. Major dams were built along major rivers like the Hoover Dam at the Colorado River, and the Grand Coulee and Bonneville Dams along the Columbia River. Oregon was in the vanguard with early forays in hydroelectric power, public ownership of utilities, and the first long distance transmission line in a sixteen mile stretch between Willamette Falls in Oregon City to the city of Portland.[4] The bohemian folk musician Woody Guthrie, advertised the dams along the Columbia and wrote songs about the river. While hydroelectric development brought many positive changes, it also brought the destruction of Native American fishing and water rights.[5]

Henry Kaiser was the leader of the Six Companies consortium responsible for the development of the Hoover Dam in Nevada, and the Grand Coulee and Bonneville Dams in the Pacific Northwest.[6] The three shipyards were located on Swan Island, the St. John’s neighborhood, and a third in Vancouver, Washington on the Columbia River. The face of Portland changed as thousands of workers were imported as engineers and other specialists from southern and eastern states. Kaiser had over 100,000 employed in the ship yards, and another 30,00 were building smaller vessels and parts at Willamette Iron and Steel, and Albina Engine and Marine Works.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt visited the Oregon Shipbuilding Co. yard on September 23rd, 1942 to mark the launching of a liberty ship that had been built in fourteen days, the Joseph N. Teal. The visit was kept a secret due to concerns over espionage on American soil even though he spoke to 14,000 workers. Kaiser, along with many Oregonians viewed the Allied cause in the war as a battle between good and evil: “We are plunged into the battle of to-be-or-not-to-be. And it is impossible to overestimate the importance in that battles of the very things, production and invention, for which you and I are responsible. The nation, indeed, depends upon us to cast the balance.”[7]

Wartime production and its concurrent demands produced labor shortages. Henry Kaiser recruited from across the country approximately 2,500 workers from New York City. The recruited were sent on trains called “Magic Carpet Specials” or “Kaiser Karavans” during the World War II era. Prospective workers, white and black, were attracted by the promise of good jobs and high wages. On September 30th, 1942 the first “Kaiser Karavan” arrived in Portland.[8] By 1945, the African American population increased to more than 20,000 and white migration into Portland increased by 100,000. Overnight the black community was transformed from a nearly invisible one to an integral part of the local and global economy. This triggered racial anxieties among government officials in Oregon. Mayor Earl Riley responding anxiously to the influx of African American migrants stated, “Portland can absorb only a minimum of Negroes without upsetting the city’s regular life.”[9] A mass meeting of 500 Albina district residents wanted to stop any further migration of African Americans into their neighborhood blaming them for increased crime, and “We Cater to White Trade Only” signs sprung up around business establishments.[10] There was a white backlash at the Kaiser Shipyards as well. The Local 72 Boilermakers Union forbade black people into their union. African Americans as result were denied skilled labor positions and were forced to join an auxiliary union with far less representation, and still had to pay their dues.

After Asa Philip Randolph President of the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters threatened to march along with 100,000 protestors on Washington to fight race discrimination in war industries, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 which opened the door for job opportunities for African Americans. The order “obligated contractors not to discriminate,” and created a Fair Employment Practice Committee, but the committee lacked enforcement and Roosevelt focused on war production rather than fight to end segregation. While it served as a victory for the black community and brought black workers to shipyards in Oregon, California and Alabama, nevertheless, segregation practices remained. Initially blacks were blocked from jobs in the shipyards and the union forbade blacks stating [they] would “pull the place down” rather give black people equal job rights at the Kaiser Portland yards. The Boilermakers Union controlled 75 percent of the skilled jobs at the shipyards. The union fell under the authority of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and notoriously held color bars preventing African American workers from joining, unlike the Congress for Industrial Organization (CIO) which did not racially discriminate.[11] The Boilermakers did everything possible to substantiate the idea that black workers were second class citizens in comparison to white workers in terms of pay scale, benefits, and protection from loss of employment. When war production demands diminished, African American workers were typically the first to be laid off along with women.

Kaiser eventually hired black workers in skilled positions without union clearance, and the Boilermakers Union was outraged. The Kaisers bowed to the union’s demands and laid off black workers. The company played a role in discriminatory labor practices and did not prohibit supervisors from enforcing segregationist policies and the downgrading of black laborers. Even before the war ended, Kaiser laid off 2,000 black workers. If Kaiser had prioritized equity and followed the recommendations of the Fair Employment Practices Commission while emphasizing war production, the outcome may have been different for African Americans in Portland. In the end, in March 1945 the Portland branch of the NAACP representing black shipyard workers won a ruling by the Fair Employment Practices Commission. The FEPC ordered the Boilermakers 72 union to allow black workers to become members, but the union protested. The war had ended before the Boilermakers had to comply with the order.

Vanport: The Flood and the Lost City

During the Second World War, a tremendous immigration influx arrived into Oregon and created a housing crisis, and there was a housing shortage for the black community. Policies of the real estate establishment and the indifference of the city housing authority fostered patterns of segregated housing during and after the war. African Americans were excluded from the city-wide housing market and mostly confined to housing in the Albina district. The Portland Council of Churches petitioned the Federal Housing Authority to provide adequate housing for black defense workers. Wartime production goals were astronomical, and there was constant pressure and demands on worker productivity at the Kaiser shipyards where job turnover was very high.

Kaiser wanted all of his workers to be stationed in Portland, but with the housing shortage this made his demand difficult to accomplish. As a result, he created the Vanport public housing project which was the largest in the nation at the time. At first it was named Kaiserville, after its creator, but a presidential order stated a housing project could not be named after a living person. The building and planning of the housing project was controlled by the Kaiser Company. By 1943, a majority of Portland’s 15,000 black residents lived either in public housing in Guild’s Lake, Fairview, and Vanport or the Williams Avenue area. At Vanport’s peak in 1944, 40,000 people lived there including 6,000 African Americans. It became known as the “Negro Project” among Oregonians even though black people did not make up a majority of Vanport’s population. For many Oregonians, racial integration in housing development was still a distant reality partly because of segregationist practices of the Portland Housing Authority. City officials before the end of the war were hoping Portland’s black residents would either move into private housing or leave the city entirely.[12]

The Portland Housing Authority stuck with the name Vanport. It was a public housing project intended for Kaiser shipyard employees and other war industries. Officials praised the $26 million project for its supposedly sturdy construction. By early November 1943, it was estimated that 39,000 lived in Vanport making it Oregon’s second largest city, and fifth among Pacific Northwest urban centers. Like the work at the shipyards, tenant turnover was high in Vanport. The city was plagued with sanitation concerns and overcrowding. Assistant Superintendent of Child Guidance at Vanport Schools, George V. Sheviakov, felt Vanport was created by “a bunch of real estate men who have their own vested interests and know about property value and rentals but don’t know beans about human living.”[13] During the war, Vanport had a 24-hour character to it. People were employed in the shipyards all hours of the day. The school program in Vanport offered extended day operations, and child service centers operated on a 24-hour basis. The city was noisy, crowded, and the apartments were cheaply constructed. Windows did not open in some units and most did not contain a thermostat. The buildings had electrical and heating issues and one 14-unit apartment building “went up in smoke suddenly.” There was a lack of telephone service, laundry facilities, and only two shopping centers with limited supplies. Vanport was located adjacent to the Columbia Slough which was badly polluted at the time, and outbreaks of water-borne disease were common. All sewage was pumped untreated into the Columbia River, and the sewer pipe that ran under the railroad tracks of the North Portland Terminal Company broke frequently. The sloughs remained polluted with raw sewage for weeks at a time. Overall, residents felt their stay in Vanport was temporary, and most could not wait to leave.

Residential requirements were lifted when World War II had ended in 1945 and an influx of veterans enrolled at the newly established Vanport Extension Center, which eventually became Portland State University. The arrival of the college brought a different and welcoming appearance to the region. Three fourths of its students were from Multnomah County and were beneficiaries of the GI Bill which offered college tuition and funds for war veterans. This offered a breath of fresh air to the community, and Vanport was starting to “take on the look of a college town”.[14]

After the war ended in 1946, government funding started to dry up for educational resources in Vanport, and summer school was cancelled while 6 thousand children roamed the streets the city. There were no private yards or play areas, and children were left on their own. Juvenile vandalism and attacks on private property became more commonplace. During the school year, classrooms were overcrowded with some running as many as forty or fifty students. Teacher turnover was high in Vanport as well. Some of the principals were known as hardened individuals who were disrespectful to parents, and wielded an “authoritarian and uncooperative attitude”.[15] School administrators like George Sheviakov were disillusioned by the majority of “vicious” and “uncaring” principals who bailed out teachers who used corporeal punishment in their classrooms. According to Shieviakov other administrators “scoffed at democracy and progressive education,” and Vanport had a difficult time maintaining quality instructors.

Segregation was practiced in Vanport from the beginning. The Portland Housing Authority continued de facto segregation practices. It was reported when an African American family moved into a building, the whole block was evacuated by whites to make way for their occupancy. Some residents were hostile to racial mixing at dances in Vanport. Blacks settled into an area that became known as the “Negro section” of Vanport. As early as 1945 there were over three and a half times as many black families in Vanport as there were in all other Housing Authority of Portland projects combined. The Oregonian printed editorials recommending that Oregonians accept the newcomer residents, and the National Association of Real Estate Board defended black residents by stating they maintain properties in the same condition as whites of similar income brackets. Dr. DeNorval Unthank, the only black member of the Portland City Club, and the Urban League urged Mayor Earl Riley to create an Inter-racial Committee and convince the Board of Realtors to help black families find homes when public housing projects are demolished. Unfortunately the mayor never responded to this request. Instead the status quo remained with the redlining of neighborhoods, agitation of white residents against people of color, and the real estate and banking sectors cordoned off blacks and other minorities into neighborhoods where many of the homes were old and dilapidated. As a result, the Housing Authority of Portland recommended that all blacks looking for housing should consider moving into Vanport, and only in the “coloreds only” sections. HAP reports indicated that it would be necessary to move white families out of the “designated colored areas” in order to accommodate the black families. The Urban League of Portland and the American Veteran’s Committee proposed a “non-segregation” policy at a meeting of Housing Authority officials, but little change came of it.

Although Vanport sat in the midst of a flood plain on the Columbia River there had never been any real concern for its safety. In May 1948, the city held about 18,700 “actual registered tenants” of which 75 percent were white. An exceptionally heavy snowpack had accumulated in the mountains that year. May produced heavy rains and warm temperatures while the Columbia River swelled with the greatest surge of water since the disastrous flood of 1894. On Memorial Day residents received a message from the Housing Authority of Portland that concluded: REMEMBER: DIKES ARE SAFE AT PRESENT YOU WILL BE WARNED IF NECESSARY YOU WILL HAVE TIME TO LEAVE DON’T GET EXCITED. When the dike along the railroad tracks broke, surging waves of water gushed through, with waves 10 feet high rushing through the streets. Cars and houses were destroyed and ripped apart, and within an hour Vanport was a lake. President Truman declared Vanport a disaster area. Individuals tried to relocate relatives, and immunization clinics were opened for people who swallowed Columbia River water. As many as 1,325 people stayed in a Red Cross shelter on Swan Island. In the panic, rumors flew about children who were trapped in a theater and perished which The Oregonian refuted. Another rumor claimed a storage facility near the shipping yards of Linnton, Oregon contained 600 bodies, but this was also unfounded.

Many in Vanport were upset they didn’t receive more advance warning about the impending crisis. The river had been at flood stage for more than a week, and precautions could have been taken to evacuate residents. Most residents received a ten-minute warning to evacuate, which was far from ideal, but it allowed available Portland Traction Company buses to arrive at the scene, along with many taxis. Because there was only one exit from Vanport, the evacuation proceeded slowly but without widespread panic. Some could not hear the warning sirens, and traffic lanes of exit were limited to one street for a city of several thousand residents. The lineup of cars on Denver Avenue was an emotionally potent image, and later the street would wash out and collapse as another victim of the flood.

The flood and resulting damage forced Vanport College to cancel its spring term. Only fifteen deaths were recorded by the Multnomah County coroner, while another ten people were reported missing, and at least seven were never accounted for. An estimated 18,000 residents lost their homes, and 4,000 were sent to temporary shelters including 1,300 who lived at the Red Cross Refugee Center on Swan Island and the rest, if they could, moved in with other families. No federal agency wanted the property and there were no real estate investors interested in rehabilitating the land, so the City of Portland used it for parks and recreational purposes. Later, under the governorship of Tom McCall, the city built Portland International Raceway, Heron Lakes Public Golf Course, and a variety of park spaces with bike trails. Governor McCall officially opened the course by hitting the first drive at a special press preview on April 29, 1971, and public play started on May 1.

Japanese Americans Internment in Oregon

During the 1920s, a harsh swell of populist based nativism swept through the nation and Oregon in response to events that transpired during World War I. John Higham in his seminal text Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, described the 1920s as the nadir in race relations in United States history. The animus towards immigrants was felt within the State Capitol in Oregon. The anti-Japanese movement came from states, labor unions, politicians, demagogues and voices within the press. “We have no room for the yellow man and we don’t want them” declared a Madras newspaper in 1920, and the citizens of La Grande and Woodburn had forced the Japanese out.[16] In Oregon, the legislature stated its opposition to Japanese immigration in a memorandum directed to all Congressional senators and representatives in 1923. Legislators in Salem were swept up by Americanization and its discontents:

“The legislature of the state of Oregon is unalterably opposed to further immigration in to the United States in excess of the present quota, and further recommends that our laws be so amended as to restrict the entrance into the United States of all Asiatics and Southern European internationals [and a] rigid exclusion of all further immigration until such time as we may fully assimilate those within our borders and give to American labor and American laws the right which is their due.”[17]

Legislators drew from nativist hysteria and associated a variety of social ills and fears of degeneration with Southern European and Asian immigrants. Their views paralleled the Ku Klux Klan which reached its peak influence among state politicians in both parties during this time. Guided by principles of Americanization, legislators were concerned over “aliens…who have not been assimilated and know little of our ideals, traditions and purposes.” They were seen as a nuisance that brought alcoholism and drug addiction into the United States and would take years “to amalgamate into the body politic.” The Oregon Congress and Governor Walter Pierce felt “aliens” endangered Oregonians and took jobs away from “100% Americans.” Putting restrictive quotas on immigration was something political leadership in Oregon fully supported.

The Immigration Act of 1924 tightened immigration quotas from Southern and Eastern Europe and stopped all immigration from Japan, which included Koreans since the nation was a colony of Japan. The law passed by Congress was in violation of the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, a mutual immigration pact between the United States and Japan.

The restriction included Japanese, Korean “picture brides” and Chinese immigrant wives of Chinese men who were American-born citizens. The Supreme Court case of Takao Ozawa v. United States in 1922 had confirmed that first-generation Asian women immigrants in Oregon could not become naturalized citizens because they clearly were not Caucasian. First generation immigrants from Japan and Korea could not become naturalized US citizens until 1952, with passage of the McCarran-Walter Act.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, racial animosity towards people of Japanese descent was boiling over on the Pacific Coast. Japan criticized the United States’ exclusion of Chinese immigrants and characterized it as America’s dislike of all Asian people. Since China was a critical ally and the United States supported their people with weapons and military equipment, government officials were intent on reversing their Anti-Asian image and repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. The majority of mass media portrayed second generation Japanese Americans as traitorous while promoting Chinese, Filipinos, Koreas, and South Asian Americans as loyal sons and daughters. Most Oregonians like their counterparts in Washington, California and British Columbia did not want the Issei or Nisei to feel at home.