4 Native Americans in the Land of Eden: An Elegy of Early Statehood

FEDERAL AND STATE AMERICAN INDIAN POLICY

The middle of the nineteenth century marked a period of incredible violence, rapid change, and forced migration of Native American peoples. After the passage of the Land Donation Act in 1850, Native American communities were besieged and displaced by settlers, miners and government officials at a furious pace. The early half of the decade was marred by massacres and war in a period of ethnic cleansing of the indigenous people of Oregon. The Euro-American colonists in the Oregon Territory gained the upper hand on Native populations through deliberate acts of violence and waves of epidemics and disease brought on by exposure to colonization and the fur trade. The settlers of Oregon aligned with federal American Indian policy and thought the “Indian question” had two answers: extermination or assimilation to Anglo-Saxon cultural mores and institutions. Otherwise, Indians of Oregon faced relocation on the reservations. During the history of the Native American experience since the American Revolution, relocation had been pursued and enacted repeatedly by an overly intrusive federal government since the Treaty of Greenville of 1795, which allowed American expansion into Shawnee, Wyandot, Delaware, and Miami territory in the Ohio Valley.[1]

In the early history of the American republic, treaties between the Native tribes and the United States were negotiated between roughly two equal powers, but as time wore on, the sovereign rights of indigenous people eroded under federal policies. Although in the ruling Worcester v. Georgia in 1832, the Supreme Court had stated Native American nations, like the Cherokee Tribe, have defensible sovereign rights to their land. President Andrew Jackson arrogantly ignored the Supreme Court ruling and claimed he held executive power to forcibly move the Cherokee with the passing of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. Relocation of Natives to reservation lands set aside by the federal or state governments involved forced migrations causing starvation and suffering. The forced migration of the Cherokee people was a jeremiad in historical memory known as the Trail of Tears to the Oklahoma Territory. This is a pattern that repeated itself in Native American history in Oregon, and many other western states. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Indian populations of Oregon and the United States had seen their lands and people shrink into small enclaves removed from mainstream society. Many American wondered if Native Americans were a dying race inevitably bound for extinction at the end of the nineteenth century.[2] OREGON TRAIL

The Oregon Trail brought in settlers from the southern, midwestern and eastern states of America to Oregon and California. A mass migration of settlers and pioneers arrived in the Willamette Valley during the 1840s. They were driven by self-interest and wanted immediate wealth in land. Pioneers imagined the Willamette Valley as a Land of Eden where poor health and financial debts could be alleviated. Unlike the common migrant heading to California, the Euro-American pioneers heading to Oregon were homesteaders rather than gold seekers or land speculators. The promise of free land from the Land Donation Act lured thousands to the Willamette Valley during the mid-1850s. The region changed from a fur-trading zone to a farming frontier through the political will of politicians, military personnel, missionaries and entrepreneurs, and of course settlers.

At approximately 2,000 miles in length, the Oregon Trail represented the longest overland trek that American pioneers attempted to the Northwest. From 1840 to 1860 approximately 300 to 400 hundred thousand people set out on the Oregon Trail with guidebooks serving as their navigation systems. Few pioneers were attacked by Natives on the Oregon Trail, although there were incidents of theft in eastern Oregon. The primary threat to the Oregon pioneers were sanitary and hygienic concerns along the trail and the spread of cholera and dysentery. Bodies were not carefully buried away from water sources, and the disease swept through the strenuous passage. Many travelers along the trail did not experience the comforts of domesticated living and urban environments. Migration on the Oregon Trail was an annual event. Oregon-bound pioneers drove wagons into the Willamette Valley through treacherous mountain passages such as Barlow Pass or braved the violent unpredictable waters of the Columbia River at The Dalles upon a raft. Sam Barlow’s toll road was an alternative option to the Columbia that also started at The Dalles, and ran along the southern edge of Mount Hood to Oregon City in the Willamette Valley. The multitude of traveling pioneers and immigrants heading into the Oregon Territory drew concern for the Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, James Douglas who acknowledged the changing appearance and intentions of emergent communities in the Oregon Territory. Douglas, whose mother was of Afro-Caribbean ancestry from Barbados, became the Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1839. Douglas was the first to be a highly ranked official of mixed racial ancestry in the Oregon Territory. Historians have concluded that Oregon’s early exclusionary laws may have been directed against people like Douglas. As early as 1831, he predicted the consequences of a large migration of American settlers to the fur trade in Oregon: “The interests of the American colony and the Fur Trade will never harmonize, the former can flourish, only, through the protection of equal laws, the influence of free trade, the accession of respectable inhabitants; in short, by establishing new order of things, while the Fur Trade, must suffer by each innovation.”[3]

Many who had been influenced by the evangelical fervor of Oregon Fever kept bibles with them because, in the words of one pioneer, “We hope not to degenerate into a state of barbarism.” Like Lewis and Clark, Oregon pioneers thought that they were entering a land of evil and darkness prone to sin and savagery. Oregon Trail settlers held unfounded fears of Native Americans and brought large arsenals of weapons, and several on the trail died from gun accidents. Crime and punishment, or any semblance of a criminal justice system, was based on frontier law. Settlers made their way across the Great Plains supporting the concept of righteous revenge and punishment for individual crimes. Lex talionis, the law of retaliation, co-opted from ancient Middle East societies like Sumer, known familiarly as “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” was the spirit of the law on the American frontier, and it was the legal tradition along the Oregon Trail. In all but two isolated cases, the death penalty was disproportionately enforced upon Native peoples in frontier law that lacked due process. Hangings ordered by the courts gave the appearance of legal lynchings and were part of the general warfare between the new and the old residents.[4]

THE WHITMAN MISSION AND THE CAYUSE Elijah White was one of the first of thirty white men who settled in Willamette Valley. In 1837, he joined the Methodist mission in the Willamette Valley. White led the first wagon train with more than 100 people over the Oregon Trail to Oregon and discovered a pass through the Oregon Coast Range to what is now the town of Newport. In 1842, more than a hundred persons and eighteen wagons rolled west under the guidance of White. It was the first party to form a multiple-wagon train in which families predominated. Elijah White was an ambitious man and a driven leader, but was a horribly cruel state official as the first Indian agent of the Oregon Territory. Arrogance reverberated through the actions of Elijah White. White attempted to run Indian affairs through draconian ideas of governance such as a law that penalized wrongdoers by flogging them. White expected the Native people to be prone to his will. He was ignorant of the Indian societies, and had no understanding of their tribal structure, or how independent bands operated. White’s laws did nothing to quell the distress among the Cayuse who lived along the Oregon Trail and experienced mass migrations of white settlers passing through their lands putting pressure upon their communities. In the spring of 1843, rumors of discontent among the Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Walla Walla suggested they might attack the settlements west of the Wallowa Mountains. The tribes were angered by the killing of their game, the opening of the Oregon Trail, and the news that Marcus Whitman, a missionary who had lived among them since 1836, would soon lead a large wagon train of more Euro-American immigrants to Oregon. White attempted to assuage the Cayuse and Walla Walla societies by establishing a code of laws to govern their society and demanded their loyalty. “If they would lay aside their former practices and prejudices stop their quarrels, cultivate their lands, and receive good laws, they might become a great and a happy people, that in order to do this, they must all be united, for they were but few in comparison to the whites; and if they were not all of one heart they would be able to accomplish nothing; that the people should be obedient and in their morning and evening prayers they should remember their chiefs.”[5] Upon Elijah White’s insistence, the Indians were to be of one heart, or unified and subservient under his command. White was an avid proponent of the “civilization program.” It became a centerpiece of federal American Indian policy and focused on converting Natives to Protestant faith and cultural values along with “agrarian virtue”: farming and American manhood. Indigenous peoples shared concerns over White’s leadership and the laws he enforced. Yellow Serpent of the Walla Walla said, “I have a message to you. Where are these laws from? Are they from God or from earth? I would that you might say they were from God. But I think they are from the earth because from what I know of white men they do not honor these laws.” An Indian named Prince commented, “People [like White] had been coming along, and promising to do them good; but they had all passed by and left no blessing behind them.”[6] Elijah White lacked an understanding of Indian diplomacy and was unable to reach mutual agreements and concessions with tribes. He was considered one of the primary causes of the Whitman Massacre with the Cayuse Indians in Walla Walla. According to the historian Stephen Dow Beckham, “Seeds of distrust between white settlers and the Indians prompted Dr. Elijah White to try to impose laws and craft a hierarchy of chiefs among the Cayuse. Going one better than the dealings of Moses with God, White handed down eleven commandments to the Plateau Indians in 1843.”[7] The Cayuse lands were bisected by the Oregon Trail, and the Whitman mission at Waiilatpu, “The Place of Rye Grass.” Marcus Whitman appealed to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) to retain their mission in Oregon. The board intended to recall him and other missionaries including Henry Spaulding. Whitman was an ardent expansionist and felt if the ABCFM closed their missions, then the United States would lose its Oregon claim. His travels across America during the winter to the board of commissioners elevated his heroic status as the “man who saved Oregon.”[8] In the fall of 1843, Dr. Whitman returned with more than a thousand emigrants from Missouri. The newcomers brought smallpox and trouble to the Cayuse Indians. The Indians, upon observation of this event and previous incidents, had reason to believe the intentions of the Whitmans were for conquest and not peace.

During the existence of the Whitman Mission, The Cayuse and the Whitmans would conflict in many ways, and the Whitmans did not prove to be tolerant diplomatic leaders. In 1841, Marcus Whitman had an argument with a Cayuse chief who insisted on payment for occupying their land. Whitman was intransigent and the chief struck him and pulled his ears. Narcissa Whitman, Marcus’s wife, considered Oregon Trail pioneers unwashed, unchurched, and foul mouthed. During her missionary work in 1840, she felt the Cayuse Indians, “…are an exceedingly proud, haughty and insolent people…We feed them far more than any of our associates do their people, yet they will not be satisfied. Notwithstanding all this there are many redeeming qualities in them, else we should have been discouraged long ago. We are more and more encouraged the longer we stay.”[9]

William Gray who was a member of the Spalding-Whitman entourage tried to punish the Cayuse for their “mischievous behavior.” Missionaries, like Gray, put emetics in melons to prevent the Cayuse from stealing from the Whitman farms. This struck the Indians as bizarre behavior, poisoning perfectly good food. Punishments of this kind were met with retribution from the Cayuse. As tensions increased, there were acts of Cayuse vandalism and broken windows on mission properties. Overall the Cayuse disliked the teachings of “agrarian virtue” and viewed the manual labor of farming as beneath their dignity. The Whitmans and their associates Henry and Eliza Spaulding in Nez Perce country were not very successful missionaries. The Cayuse were resistant to the religious conversion of the Whitmans, whereas the Nez Perce were initially receptive to Christian evangelism. Tuekakas (Old Chief Joseph) of the Nez Perce welcomed baptism, but later renounced his faith when he felt he had been deceived by government officials and ABCFM missionaries. The Whitmans knew the situation with the Cayuse was bleak since their mission on the Walla Walla River was only twenty-five miles upstream from the Columbia River, and that meant the Cayuse would be exposed to various newcomers trickling into the Oregon Territory bringing diseases with them. Many who were struck sick along the trail from unsanitary conditions and rampant disease brought epidemics of measles and dysentery into the region. Fifty percent of the Cayuse died in less than two months after contact with the settlers in the Whitmans party. The disease did not affect white children the same way it did Cayuse children, who typically did not recover. Already suffering from a spread of diseases, the Cayuse saw the pioneers as a great uninvited and menacing invasion. Whitman only aroused suspicions further by continually providing food and sanctuary for Euro-American migrants arriving on the Oregon Trail, thus jeopardizing the goals of the mission with the Cayuse. Letters written to the Hudson’s Bay Company conveyed the increasingly tense situation among the Cayuse and the impending doom for the Whitmans: “I presume you are well acquainted that fever and dysentery have been raging here in the vicinity, in consequence of which a great number of Indians have been swept away but more especially at the Doctor’s [Whitman] place, where he had attended upon the Indians. About thirty souls of the Cayuse tribe died, one after another, who evidently believed the Doctor had poisoned them, and in which opinion they were, unfortunately confirmed by one of the Doctor’s party.”[10] In November 1847, a group of Cayuse men attacked the Whitman mission, murdering Marcus and Narcissa, and several others. It was an event known as the Whitman Massacre. Upon hearing of the Whitman attack, James Douglas, Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, wrote to the provisional governor of Oregon, George Abernethy. He referred to the attack as a gross injustice without justifiable cause and the Cayuse must receive immediate retribution for the murder of the Whitmans who were completely blameless.

“One of the most attrocious [sic] which darkens the annals of Indian crime. [The Whitmans] have fallen victim to those remorseless savages who appear to have been instigated to this appalling crime but a horrible suspicion which had taken possession of their superstitious minds, in consequence of the number of deaths form dysentery and measles…Dr. Whitman has been laboring incessantly since the appearance of the measles and dysentery…and such has been the reward of his generous labors.”[11] George Abernethy wrote to the Provisional Legislature of Oregon upon hearing the news from the chief factor, “This is one of the most distressing circumstances that has occurred in our Territory, and one that calls for immediate and prompt action…I have no doubt but the expense attending this affair will be promptly met by the United States government.” Upon knowledge of the letter from Abernethy and the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Provisional Legislature in Oregon City adopted the motion of the Jacksonian Democrat, James Nesmith, politically aligned with Joseph Lane, who saw his duties tied solely to the protection of Euro-American settlers, and the immediate prosecution of the Cayuse Indians. “Resolved, that the Governor is hereby required to raise arms and equip a company of riflemen, not to exceed fifty men, with their captain and subaltern officers, and dispatched them forthwith to occupy the mission station at The Dalles, on the Columbia River, and to hold possession of the same until reinforcements can arrive at that point, or other means to be taken as the Government may think advisable.” After serving in the provisional government, Nesmith served in the Oregon Volunteers in the Cayuse War as a captain and continued his military career fighting various Indian wars. He also served as a captain in the Rogue River Indian Wars and as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1857 to 1859, where he engaged the southern coastal Indians of Oregon as an inexorable eliminationist that he could “see no way that the settlers can rid themselves of the nuisance, unless they can hit upon some mode for their extermination, a result which would occasion no regrets at this office.”[12] The first war in Oregon broke out between Cayuse and 500 Oregon volunteers from the Willamette Valley who were soldiers raised by the Oregon Provisional Legislature. Some of the Cayuse had no knowledge of the intention to kill the Whitmans. The settlers learned that the Cayuse had a law that when one committed murder, one forfeited his own life. George Abernethy offered up a declaration to the chiefs of the Nez Perce and other tribes: “We want the men that murdered our brother Dr. Whitman, and his wife. We want all of these to be given up to us, that they may be punished according to our law.” The Cayuse tribal leaders turned over five members of their tribe to stand trial. This was the first trial where judicial proceedings were formalized and recorded in Oregon. In 1850, five Indians were hanged in Oregon City on Main Street along the Willamette River in retaliation for the Whitman incident. Public executions in the early stages of Oregon’s history were massive public spectacles, and if the victim was nonwhite, then the crowds in attendance would increase in size with greater fervor and interest. Over 1,000 Oregon settlers attended this spectacle of retributive capital punishment of the Cayuse. Joseph Meek, United States marshal, used his Indian hatchet to cut the rope and drop the five Cayuses to their death. For Meek, this execution was personal and brought him partial vindication in the legal culture of lex talionis. Meek left his daughter under the care of Narcissa Whitman at their mission where she died along with the Whitmans at Waiilatpu. Meek went to Washington D.C. and presented the news to Congress about the Whitman tragedy. He also brought along petitions from Willamette Valley settlers requesting statehood. This spurred Congress to create the Oregon Territory, the first American territory west of the Rocky Mountains.

Joel Palmer and the Nez Perce

Joel Palmer, who became Superintendent of Indians Affairs thought the Nez Perce understood the law of the Christian God which they had welcomed in their community. After the downfall of the Whitman Mission, Piupiumaksmaks, Yellow Bird of the Nez Perce, had assured Palmer and Oregon government officials that they no longer were allies of the Cayuse. The Nez Perce felt the neighboring Cayuse had virtually isolated themselves from any alliances with other tribes. Oregon officials, through diplomatic channels, drew together an enduring chain of allegiance with the Nez Perce, who foresaw that retaining the “power of God and his law” would win them favor in negotiations, and Tuekakas (Old Chief Joseph) and his son Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt (Thunder Rolling Down the Mountains), or Chief Joseph converted (although briefly) to Christianity. After the Civil War, gold was found in Nez Perce country in the Wallowa region. Relations between the Nez Perce and the American government quickly deteriorated, and the alliance they once held was broken.

For Joel Palmer, he felt peace was attainable, and the settlers of Oregon could reach an agreement with the Nez Perce that “this land will be purified, and in no other way will we have peace.”[13] Palmer was one of the more sympathetic and diplomatic government agents to the Natives of Oregon, but often his hand was forced by external pressures that were beyond the reach of his authority, especially by the settlers of Oregon. He brokered many of the early treaties with the Oregon Indians including the end of the Rogue River Wars which resulted in the forced relocation of the Siletz and Tolowa tribes to the Grande Ronde Reservation also known as the Oregon Trail of Tears.

Many of the settlers became enraged with Palmer for his empathetic diplomacy because they felt he was too soft with the Indians, and should be more forceful with them. The settlers felt they should not have to accommodate the indigenous people in diplomacy. Manifest Destiny had permeated the minds of settlers and the relocation and extermination of Native peoples proceeded without hesitation.

Kalapuya of the Willamette Valley

The land grab of the Oregon Territory was rapid and extensive in the Willamette Valley. In the early years, settlers of the Kalapuya region would turn their livestock out onto the unclaimed and unfenced open prairies. Stock raising was an important part of settlers’ work, and cattle and swine ran free everywhere eating camas bulbs and other tubers the local Kalapuya had traditionally harvested for thousands of years. The arrival of Euro-American settlers and explorers caused the Kalapuyas to experience demographic collapse. Their culture was in shambles, their villages were destroyed, and communal food gathering activities no longer existed. Around the lower Willamette Valley, malarial epidemics in the 1830s killed thousands of Kalapuyas. The traditional means of curing illness by calling on a shaman or going to the sweat lodge did not stop the spread of disease and death. In particular, the sweat lodge proved to be fatal when Indians exposed themselves to high temperatures in the lodge and then immersed themselves in a cold bath afterward. This in turn would exacerbate the illness and become a deadly combination. The only threat the Kalapuyas posed was in the settlers’ minds. Kalpuyas were starving while the settlers from the Appalachia area bore militant attitudes toward Native Americans. President Millard Fillmore created the Willamette Valley Treaty Commission (WVTC) in 1850 to secure the cession of the Willamette Valley to the United States through the Land Donation Act and the removal of all the Kalapuyas and Molallas to east of the Cascade Mountains. The tribes refused to be moved to the Great Basin region of eastern Oregon, where the natural environment was vastly different from their homeland and far less accommodating. The commissioners seemed oblivious to the tenure of the Wasco, Tenino, and Northern Paiute on the Columbia Plateau to the east. The WVTC tried to encourage the Santiams to move to a tract of swampy country that contained grazing for livestock. The commissioners thought this would be suitable for the Santiams, and offered to pay three times the amount of the value of their Tribal lands. At the Santiam Treaty Council, Alquema, one of the council leaders stated that the commissioners’ offering was completely insufficient: “It would tie us up into too small a space; it is no reserve at all. Some of the whites are foolish. They would whip and kick us and tell us to go Home. We want the whites on the other side of the creek. They would be too close to us if we let them be so near our homes. They would ill treat us…you want us still to take less. We can not do it; it would be too small; it is tying us up into too small a space. We understand that it may be better for us (to move east of the Cascades) but our minds are made up. We do not wish to leave…we would rather be shot on (this land) than to remove.”[14] The Treaty with the Kalapuya of 1855 forced the remnant Kalapuya and other tribes of the Willamette Valley to cede the entire Santiam watershed to the United States. The Santiam of the Mid-Willamette Valley wished to retain their lands in the north half on the forks of the Santiam River, but they were only given half of their holdings. The land the Kalapuya ceded reached from Champoeg and Aurora south along the western side of the Willamette River to the vicinity of Brownsville. It included the valley from the western Cascades to the Willamette River and embraced the drainages of the Pudding, Santiam, and Calapooia Rivers. Eventually the people of the Santiam region would be relocated to the short-lived Umpqua reservation in southern Oregon, and the Kalapuya and Molallas were resettled in the Grande Ronde Reservation in the Yamhill Valley.

GOLD MINING AND VIOLENCE IN SOUTHERN OREGON

Oregonians mined an estimated five million dollars of California’s gold. More importantly, California’s booming economy provided Oregon with a growing nearby market for wheat, lumber, and beef. The discovery of gold in Josephine Creek created a boom for miners and merchants in Southern Oregon. The gold bonanza in Southern Oregon stimulated the state’s economy by expanding commerce and trade in the markets and agricultural sector. The central and northern Willamette Valley, along with the city of Portland, benefitted and experienced tremendous economic growth and development. For gold seekers, Portland did not seem to be so much a city as it was a vast warehouse where goods from the farms and settlements along the Columbia and Willamette rivers were gathered for shipment to San Francisco and foreign markets.

When gold was discovered in the black sands north of the Coquille River of Oregon in Coos County region in 1853, things took a violent turn for the tribes of south and southwest Oregon. More than a thousand miners flooded the region in search of quick wealth and prospects from nearby Rogue River and Gold Beach. They established a town called Randolph near the Nasomah village of the Coquille tribe near present-day Bandon. The miners of Randolph disregarded the Coquille and the other local tribes. The Coquille’s land was invaded and exploited and native women were sexually violated. Tensions built between the two sides until the Euro-American miners resorted to extermination of the local indigenous people. The miners of Randolph formed the Coos County Volunteers and they were led by their captain George Abbott. The miners created bogus complaints to curtail the movement of the Nasomah, and after a clash between a native and a white man, the miners descended upon the Nasomah village while they were asleep. Abbott and the Volunteers killed twenty-one of the Nasomah and burned down all of their homes. The villagers were outnumbered and outgunned and had only three functioning guns. Indian Agent F. M. Smith described the terrorist actions of the Volunteers as “a most horrid massacre … a mass murder perpetrated upon a portion of the Nasomah.”[15] The Coos County Volunteers audaciously billed the federal government for services rendered to the state of Oregon.[16] They felt they were providing security services to allow the commerce of gold mining to flow freely without interference from the indigenous people. The miners of Randolph afterward passed seven resolutions justifying their slaughter.

Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer did not see the incident in the same way, and forwarded a letter to Washington from the Sub-Indian agent F.M. Smith of Port Orford stating, “These miscreants, regardless of age or sex, assail and slaughter these poor, weak and defenseless Indians with impunity as there are no means in the hands of the agents to prevent those outrages or bring the perpetrators to justice.”[17] Palmer requested the federal government to bring in a military presence to protect the Coquille amidst the opinions of outraged settlers of the community whose “sense of justice and humanity” had been repulsed by the wanton inhumane violence of the miners and their militia. He felt the settlers who deplored the conduct of Abbott and his volunteers were forced into silence. When the reports were published, Palmer and Smith were given death threats from the miners. Smith fled Port Orford and abandoned his position as Sub-Indian agent. The Coquille lost 700,000 acres of their lands, and many were ordered by Palmer to move to the Grande Ronde Reservation in Yamhill Valley. Palmer concluded the Coquilles lives were in danger and needed to be moved for their own safety. The stark reality of American Indian relations with Euro-American settlers frequently was resolved with relocation because otherwise Native Americans’ lives were in danger if they remained.

Before Smith departed from his post in 1854, Benjamin Wright was appointed by state officials to be the next special sub-agent of Indian Affairs at Port Orford. Wright was considered a “hero” from Yreka who according to the white community was feared and respected by the Natives. Wright was the Indian agent responsible for brokering interactions between the federal government and all tribes south of Coos Bay, Oregon. Many Indians considered this a clear indication they were targeted for extermination. Whereas miners and other unsympathetic settlers, saw Wright as the solution to their “Indian problem”. For Ben Wright, alcohol was a precursor to violence revealing his diabolic nature and his murderous intentions towards the indigenous people of Oregon. Under his corrupt leadership, Native American communities suffered. It was well known that he kept Native women captive for his sexual convenience, and took trophies such as scalps, noses, and fingers from the people he and his posse murdered. In 1852, Wright led a party of Yreka residents who massacred and mutilated forty Modoc in southern Oregon. This event would later be known as the Ben Wright Massacre, and it played a major role in the precipitation of the Modoc War, discussed later in this chapter. According to another account, Wright was drunk and tried to sexually solicit Chetco Jenny, his government-appointed interpreter. She struck him, and Wright scandalized even the miners at Port Orford when he stripped and whipped her as she ran naked through the streets of town. Chetco Jenny would have her revenge later, when she had Ben Wright killed.[18] Palmer wrote a letter to Oregon governor George Law Curry in 1856 warning him about the bleak situation for the Indians of Southern Oregon. “You are not ignorant of the feeling . . . which, in many districts looked to the system of extermination as the only available policy to be pursued by the Government. . . a history of the settlement and occupancy by whites, of Southern Oregon and Northern California would be a history of wrong against the red man; and the cunning, the violation of faith, the treachery and savage brutality said to be the characteristics of that people, have been practiced towards them to a degree almost inconceivable, by the reckless portion of whites who have cursed that land with their presence in the last six years.”[19]

GOLD MINING AND THE ROGUE RIVER WARS

As time went on, settlers moving into Oregon grew more resentful and hostile to Native peoples. The outbreak of the Cayuse War in northern Oregon and the sensationalist press coverage of the Whitman Massacre fueled animosities toward the Indians. Pioneers held to the maxim that “the only good Indians were dead ones”, and it applied to the Rogues as well. The Rogue Indians share a commonality with the Nez Perce: they were given their name by Euro-American settlers. They were labeled “Rogues” or “Rascals” because they resisted trespass and wanted to defend their people from intrusion of Euro-American settlers. The “Rogue” peoples included multiple Athabascan (Tututni) tribes, specifically the Upper Coquille (Mishikwutinetunne), Shasta Costa, Tututni, Taltushtuntede, Dakubetede, Latgawa, Takelma/Dagelma, and Shasta. In 1850, the population was estimated to be about 9,500 people. The Oregon Spectator published a letter in 1847 from Charles Pickett, the first Indian Agent for the area, cautioning settlers to: “Treat the Indians along the road kindly, but trust them not. After you get to the Siskiyou Mountains, use your pleasure in spilling blood, but were I traveling with you, from this on to the first sight of the Sacramento Valley my only communication with these treacherous, cowardly, untameable rascals would be through my rifle.…Self-preservation here dictates these savages being killed off as soon as possible.”[20]

Pickett saw the Rogue Valley people as merely obstacles to Euro-American and settlement and commerce, and thought that elimination was the only viable option for the United States. The Oregon City Oregon Spectator stated, “A general disposition appears to pervade the minds of the whites to kill all the Indians they come across [in the Rouge River Valley]. The extinction of the entire race in that region is the most unanimous sentiment.”[21] When miners reached the Willamette Valley, they corresponded with the territorial governor, Joseph Lane, to help them recover the gold they had lost through encounters with the Native population. In June 1850, Lane assembled a group of fifteen men and headed down to the Rogue River region with the intention of recovering the gold and signing a treaty with the Native groups. The previous year, in a letter to John Gaines, governor of Oregon Territory, Lane complained, “They (the Indians) will cut off our trade with the mines, kill many of the whites traveling in that direction, and seriously injure the prospects and interests of the people of this Territory.”

An all-too-familiar chain of conflict escalated between Natives and whites in the summers of 1851 and 1852 as large numbers of settlers began to pour into the Rogue River Valley. Root and seed fields maintained by the Takelma “(those) along the river” were turned to grazing land, and indigenous animal populations were decimated by reckless hunting. People faced increasing suffering and starvation, questioning why their lives were being destroyed by invaders. Miners on Jackson Creek and the news of gold strike spread during the spring of 1852. Hundreds more men joined the rush to the Rogue Valley, and a new boom town, Jacksonville, began to grow in the foothills. By that summer trouble was brewing in the region of the Klamath and Rogue Rivers. One member of a volunteer militia wrote, “The Cry was extermination of all the Indians by the whites and the company began to break up into small companies to go to different Indian Rancharies to clean them out.” On July 18, 1852, miners attacked a village at the mouth of Evans Creek, killing several women. The volunteers involved in the incident were honored for their actions at a public dinner of song-making and merriment where over 120 people were in attendance. They were toasted by J.W. Davenport of Jacksonville who proclaimed, “On behalf of those who contributed to this dinner, may your generous acts on this occasion, be honored throughout this Valley; may its emblematic influence excite the independence of our Union, and may you live to see the time when the Indians Rogue River are extinct.” After the toast, the attendees broke out into a song to celebrate their heroic victory over the Rogues: “Rise, rise ye Oregon’s rise, rise rise ye Oregon’s rise, Hark hark, hark, how the eagle cries Rise, rise, ye Oregon’s rise on the Indians.” Jacksonville became the epicenter of ethnic cleansing of Native Americans. On the 7th of August 1853, miners captured two Shasta men, one on Jackson Creek, and the other on the Applegate Trail. They were brought to Jacksonville and on examination it was found that the bullets belonging to one of their guns were the same size of the one used to kill a miner a few days before. The evidence and circumstances were enough to identify the men as the murderers, and they were hanged before 2 o’clock the same day. From the diaries of Benjamin Dowell, a packer and a respected lawyer, insights can be gained into the nature of ethnic cleansing in an environment of bloodlust and fanatcism: “Late in the evening of the day those Indians were executed, a small innocent boy about nine years old was brought to Jacksonville by three men from Butte Creek, with whom the boy had been living. The poor little boy on being discovered by the miners [was] taken to a place near where David Linn’s cabinet shop is now standing, and near where the scaffold where the two Indians were still hanging. I mounted a log near by, and called the attention of the vast crowd to the solemnity of the act they were about to perpetrate. I called on them to punish the guilty, but to spare the life of the innocent child. While pleading at the top of my voice the crowd gathered around the hangman’s tree. Someone called out “what will you do with the boy.” I replied, I will take him to a hotel and feed him. I went to him and took him by the hand and started up California Street when Martin Angel came up on horseback and without alighting commenced to harangue the mob against the murderous Indians. He said: “The war was raging all over Rogue River Valley, we have been fighting Indians all day; hang him, hang him; he will make a murderer when he is grown, and would hang you if he had a chance.” The mob at once seized the boy and threw a rope around his neck, which I succeeded in cutting twice…. The excitement was so great that I found that my own life was in danger, and I had to withdraw. In a moment more the boy was swinging to a limb. I turned away with a sad heart at this inhuman conduct towards the innocent child, against whom no crime was charged. No mob ever committed a more heartless murder than this.”[22] The miners not only hanged the Natives they could find in Jacksonville, but they also decided to attack a Shasta village on Bear Creek. Afterward, a parade of volunteers from the Crescent City Guard marched through Jacksonville “waving a flag on which was inscribed in flaming colors: Extermination.” When the miners experienced a temporary layoff in January 1855, nineteen men from Sailor’s Diggings, a large gold-mining settlement a few miles north of the California state line, decided to attack Indian lodges along the Illinois River. At one of the villages, they found only seven women and three children. They shot the pregnant woman nine times and killed the children before returning to camp to get reinforcements. But the other miners wanted no part in this. Lieutenant George Crook sadly recalled, “It was of no unfrequent [sic] occurrence for an Indian to be shot down in cold blood, or a squaw to be raped by some brute. Such a thing as a white man being punished for outraging an Indian was unheard of. It was the fable of the wolf and the lamb every time.”[23] The Rogue River Wars broke out into waves of violence in 1855 and 1856, where both sides attacked each other, and the level of brutality escalated. An Indian girl fetching water for her employers was shot, and her body was thrown in the river. An Indian boy in his early teenage years was hung from the limb of a tree, and another was caught and had his throat cut. Prominent citizens wrote to Governor George Law Curry, who made a proclamation condemning the violence against “peaceable Indians,” but it was he who had sanctioned the violence against the Rogue River peoples in the first place. It was a wave of appointments for office and profits that were enabled by Governor Curry in the extermination of the Rogue peoples. Few on the Oregon frontier besides Joel Palmer, dared speak on behalf of the Native people for fear of violent retribution, and John Beeson was one of the rare examples. Beeson was a Methodist minister from Illinois who helped fugitive slaves escaping the south on the Underground Railroad and was lured to Oregon because of the Land Donation Act. Beeson felt the settlers of Oregon were in violation of the Table Rock Treaty of 1853 between American officials and the Takelma, Shasta, and Dakubetede Indians of the Rogue Valley. He protested against the hunting down and killing of Natives during the Rogue Indian Wars. Beeson wrote an opinion piece, “Address to the Citizens of the Rogue River Valley,” published in the Oregon Argus newspaper of Oregon City. Beeson would be forced to leave the Bear Creek area between Medford and Ashland, and lived under government protection. In his editorial, he saw the war as a “cruel injustice” and an “unnecessary waste of the resources of our common country.”

“You have sought to destroy the testimony by asserting that it is nothing but the production of a low and depraved intellect. Having come to this country in acceptance of the Governmental offer of land for occupancy, I honestly believed the original owners had received a fair compensation and that the treaty stipulation guarantying [sic] protection and forbidding private war would be promptly fulfilled. When I saw that we had possessed ourselves of the fertile valleys and creeks of the most pleasant homes of the Indian, and exposed him to violence and outrage of the evil disposed and vicious, I could not but feel the injustice we were doing.”[24]

Beeson observed that the Yreka newspapers of northern California were fanning the flames of racial animosity by presenting extermination of the race as the only tangible possibility for miners. Beeson attempted to organize peace talks, but the people of Jacksonville would have nothing to do with it. Wanton vigilante violence continued after the massacre. The local press maintained a stream of propaganda that painted an entirely different picture of the Rogue River Indian situation. Beeson would catch the national attention of social reformers, such as the abolitionist Lydia Marie Child, but to no avail; the killing and dislocation persisted.

Joel Palmer toured the area in the spring of 1855 and became aware of the dismal future that lay ahead for the Rogue Tribes. Palmer saw that the continuing problem between the Indigenous population and Euro-American colonists as a conflict over land rights. It was clear that some of the troubles in the Rogue River Valley stemmed from the mishandling of the Land Donation Act. Even with treaties in place, in several instances, the federal government failed to clear Native titles to land before allowing white settlers to make their claims. Troubles over land claims have historically been a problem in the American frontier, especially in the Appalachia region. Superintendent Palmer had anticipated these problems and explored possible reservations sites along the north and central coast in the vicinity of the Siletz River and on the east side of the Yamhill River. This is where the Grande Ronde Reservation would be designated. Many within the territorial House of Representatives called for Palmer’s resignation. They thought Palmer was giving too much favor to the Indians and depriving the settlers from land in the heart of the Willamette Valley. Palmer began to remove the Umpquas; then the Mollala and Kalapuya Indian bands reached the Grande Ronde Reservation on the Yamhill River. The reservation was established by Executive Order on June 30, 1857. When military protection was obtained, 400 Indians left the Table Rock Reservation in the Rogue Valley, which had been established in 1853 to attempt to quell the conflict, for a 263-mile march along the Applegate Trail, during the winter, through the snow-covered mountains to the Grande Ronde Reservation. The equipment and supplies for the journey was inadequate, and eight people died along the way through the Applegate Trail. There was bad weather and a lack of food. The Rogues were pursued by the “self-styled Indian executioner” Timoleon Love who killed one of the Indians. He was arrested for murder but soon after escaped from prison in Winchester, Oregon. After their arrival the transplanted Rogues stated the conditions at the Grande Ronde Reservation were awful and sickness was running rampant among them. The reservation was ill-suited for agriculture; the soil was clay-based, rocky, and barren; and shelter, clothing, and subsistence were sorely lacking. Federal legislation did not address the issues of the Grand Ronde Reservation until the 1970s.

THE MODOC WAR

The Modoc people lived in villages around Tule, Lower Klamath, and Clear Lakes in southern Oregon and northern California. The incursion of Euro-American miners and settlers into the region brought violence into these communities as well. Yreka miners were known for using Native women as prostitutes and boys as servants. An incident involving Benjamin Wright and close to forty Modoc leaders would catch the attention of the nation, and lead into one of the last “Indian Wars” – The Modoc War. There was disagreement between the white pioneers and Natives about the events that triggered the war. It is alleged that Wright and a group of Yreka “volunteers” invited several Modoc to a feast, and several witnesses claimed that Wright intended to poison them with strychnine, but the leaders declined their invitation. Instead Wright planned to ambush them and surrounded the Modoc village at night. The following day Wright and his posse attacked the village, and killed Kintpuash’s (Captain Jack) father. The fleeing Modoc “were searched out from the sagebrush and shot like rabbits. Long poles were taken from the wickiups and those taking refuge in the river were poked out and shot as they struggled in the water”. Forty-one of the forty-six Modoc there were killed, including many women, and none of the attackers were injured. Schonchin John was one of the five survivors of the massacre. Wright’s men scalped and mutilated the bodies of the dead. When they returned to Yreka with their trophies, they were proclaimed heroes.

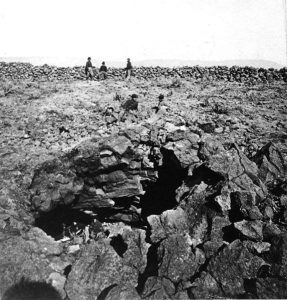

Settlers moved into Modoc territory during the Civil War, and in 1864, the Modoc yielded to pressure and signed a treaty that committed them to giving up land in the Tule Lake country near the Oregon-Californian border and relocating to the Klamath Indian Reservation. It provided the Modocs be placed on a reservation located north of what was then Linkville, Oregon, and is now called Klamath Falls. The Modocs were to share the Klamath Reservation with the Klamath Indians, their archrivals, along with the Yahooskin band of Paiutes. In the treaty, the three Tribes, known collectively to this day as the Klamath Tribes, ceded their title to approximately 22,000,000 acres of aboriginal lands to the United States. In return, they retained 1,900,000 acres for a reservation. It was expressly stated that the Tribe would be secured “the exclusive right of taking fish in the streams and lakes, included in said reservation.” The Klamath Tribes ceded all of their land in exchange for $8,000 worth of supplies for five years on the Klamath Reservation. Modocs were outnumbered by the Klamath, who demanded that the Modocs return a certain portion of their cut timber as rent for living on their part of the reservation. Life would become particularly intolerable for the Modoc. The Klamath would harass Modoc women, and their property was destroyed. The reservation was on Klamath land, not Modoc, and the Modocs were treated as interlopers. Conditions were poor, and promised supplies never materialized. White officers seized Klamath women as concubines, and agency employees smuggled in whiskey to the Natives. Captain Jack (Kintpuash) of the Modoc stated, “I do not want to live upon the reservation, for the Indians there are poorly clothed, suffer from hunger, and even have to leave the reservation sometimes to make a living.”[25] Many Modoc worked off the reservation as house servants for Yreka miners. Alfred B. Meacham, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Oregon in 1869, was stunned to have one of his agents comment that the solution to the Indian problem was to “wash the color out,” implying that intermarriage between Euro-Americans and Native Americans was the best idea, and perhaps an early iteration of a government authorized eugenics. American soldiers took in Native American women, causing Meacham to issue regulations across Oregon forbidding plural marriage in Oregon. Oregon had banned racial intermarriage in their state constitution in 1866 with a particular focus between whites and Native Americans, or Hawaiians, Chinese, and African Americans.[26] As frustrations mounted, there was a split in Modoc leadership. Schonchin John, who had survived the Ben Wright massacre, tended to cooperate with reservation authorities, while Kintpuash, whose father likely died in the massacre, did not. Shortly after the Modoc started building their homes, the Klamath began to steal lumber from the Modoc. After the Indian agent responded that they could not be protected against the Klamath, Captain Jack’s band moved to another part of the reservation. Several attempts were made to find a suitable location, but the Klamath continued to harass the band. Jack left with his followers to live along the territory north of the California border. The federal government interceded again. It responded to complaints by settlers near Tule Lake by sending out a detachment of cavalry in 1872. After continued exploitation by the Klamath Indians and American soldiers, Captain Jack led the entire Modoc Tribe—371 men, women, and children—off the reservation and returned back to their homeland. Kintpuash and his men fled to the Lava Beds, where they held off a U.S. military force of a thousand soldiers equipped with mortars and howitzers.

On April 11, 1873 a meeting was arranged between Kintpuash and General Edward Canby by Toby Riddle, a Modoc interpreter working for the U.S. government. General Canby was warned by Riddle to not trust Kintpuash during their negotiations with the Modoc. Canby confidently thought the Modoc would not dare violate a flag of truce or attempt an assassination with soldiers surrounding their position. He underestimated Kintpuash who ambushed the meeting and shot Canby in the face, killing him. Reverend Thomas was mortally wounded in the attack, while Riddle the other peace commissioner escaped. Canby was widely popular Union general and known for his efforts in quelling the draft riots in New York City during the Civil War. The press boiled in outrage over the murders of Canby and Reverend Thomas. The Modoc no longer had the support of mainstream Americans, who had sympathized with their cause until then. General Tecumseh Sherman ordered the troops surrounding the Lava Beds to attack the Modoc, advising, “You will be justified in their utter extermination.” Kintpuash, along with his wife and daughter, were captured by Army scouts on June 1, 1873, marking the end of the war and the in the minds of many Modoc, their tribal sovereignty. The Modoc War was the costliest Indian war in United States military history, in terms of both lives and money. Many settlers were shocked by the ability of such a small group of Modoc to hold back their position for over six months against U.S. Calvary troops. According to historian Doug Foster in recent historical memory, it was a “David and Goliath War”. However, American newspapers at the time felt compelled to stick to the narrative of the “primitive” culture of Native peoples so that the aggressive tactics of the military could be justified. This attitude is portrayed by the opinion of the Attorney General, submitted to the New York Tribune in 1873: “[The Indians] were mere outlaws and marauders, no more entitled to belligerent rights than so many ruffians escaped from Sing Sing. There can be no war except between independent nations, or a government and its revolted subjects. To recognize the sovereign character of a band of two-score Digger Indians is preposterous; to treat their plundering and scalping expeditions as a rebellion is not less so.”[27] The Justice Department sided with the opinion that the Modocs could not be considered as an independent foreign nation and they were comparable to “Digger Indians.” The Modocs responsible for Canby’s death, however, would be tried as war criminals, which would imply their foreign sovereign status. The trial and conviction would mark the first time that Indians were tried in a court of law as war criminals rather than as murderers. The retribution against the Modocs was swift. On October 3, 1873 an estimated two thousand people attended the hanging of the four men. Every member of the Modoc Tribe, including children, were forced to watch as a show of disciplinary force. Afterward, the rest of Kientpoos’s band were exiled to Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma. According to Lynn Schonchin, former chairman of the Klamath Tribes, forcing the tribe to watch the hangings “was a lesson in power”, and a way of telling them “they had no rights, no freedoms…if you stand up this is what we’re going to do to you”. When the bodies of Schonchin John and Kientpoos were taken from the scaffold, an army surgeon cut off their heads for shipment to Washington, D.C. For over a century, their skulls sat on the shelves of the Army Medical Museum, and later the Smithsonian Institution, before finally being returned to the Klamath Tribes in the 1990s. Few knew that Kintpuash had filed applications with the federal government to receive legal title for their ancestral homeland along Lost River. But the Modoc were not allowed to acquire any lands this way because as Indians, they were not considered to be citizens of the United States.[28] Recently in historical memory, State Senator Fred Girod of Stayton passed Senate Concurrent Resolution 12 in the Oregon Senate in 2019. It was an official apology to the Klamath Tribes: “that we, the members of the Eightieth Legislative Assembly, commemorate the Modoc War of 1872-1873, and we recognize and honor all those who lost their lives in that costly conflict; and be it further resolved, that we express our regret over the execution of Kintpuash, Schonchin John, Black Jim and Boston Charley in October 1873 and for the expulsion of the Modoc tribe from their ancestral lands in Oregon.” NEZ PERCE WAR

The Nez Perce War in the Wallowa Country of Oregon marked one of the closing chapters of Indian wars in Oregonian and American history. The Nez Perce treaty of 1855 had restricted the Wallowa Nez Perce band to northeastern Oregon giving up their ancestral lands and some were forced to move to the Umatilla Reservation along with the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla tribes. The treaty allowed the Nez Perce to remain on their homeland but with a catch, they had to relinquish 5.5 million acres of their land of their 13 million acres holdings for a minimal cash payment.

But miners discovered gold along the Clearwater in 1861, and the resulting rush brought money, alcohol, and violence to the reservation Nez Perce. It also reduced the Indians lands. In 1863, trespassing whites discovered gold within Nez Perce boundaries. A new agreement was reached that shrank Nez Perce holdings to about 750,000 acres. The treaty stipulated that each family would get but twenty acres. Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekht (“Thunder Traveling to Loftier Mountain Heights”), also known as Chief Joseph, inherited a leadership role from his father, Tuekakas (Old Joseph). Aware of the aggressive posture of the United States government in its reduction of Nez Perce lands, he insisted the treaty did not apply to his band of Nez Perce because his father never signed it. The treaty, now located in the National Archives, was never seen by Young Joseph, and he was unaware that his father had signed the treaty after negotiations with Isaac I. Stevens, Governor and Superintendent of Indian affairs for the Territory of Washington, and Joel Palmer, Superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory. President Grant initially agreed with Chief Joseph and set aside the land for the Nez Perce in 1873. Land-hungry whites pushed the issue, and the government changed its mind. Whites would not let the Nez Perce remain in the Wallowa Valley. The residents of northeastern Oregon were dead set against it. An article in a La Grande newspaper summed up the white people’s attitudes. The piece remarked on a pair of “splendid Indians” who “unlike any others of their race” were “calm, quiet and considerate,” who “even refuse whiskey though offered to them.” What was the secret of their exemplary manners and habits? They had for “many days” been hanging from “a tree with a rope around their necks.”[29] General Oliver Otis Howard, Civil War hero, Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau and founder of the black college Howard University, ordered Chief Joseph and his tribe to move out of the Wallowa Country in 1877. Howard humiliated the Nez Perce by jailing their old leader, Toohoolhoolzote, who spoke against moving to the reservation. The other Nez Perce leaders, including Chief Joseph, considered military resistance to be futile; they agreed to the move and report to Fort Lapwai, Idaho Territory. General Howard gave them the unreasonable ultimatum to evacuate the Wallowa Valley in thirty days. In the end six hundred men, women, and children, along with 2,000 horses, headed across the Bitterroot Mountains to the plains of Montana, where the Crow tribe lived. The Nez Perce were hoping to form an alliance to resist against the United States Army, but the Crow did not want to sacrifice their good standing with the federal government. The Nez Perce then decided to head to Canada to meet with Sitting Bull and his people as they were hotly pursued by General Howard and his troops. With Howard and his men in hot pursuit, the Nez Perce would scatter frightened tourists in Yellowstone, which had been established as a national park a few years earlier, on their mad dash to the international border. Just forty miles from their goal, the Canadian border, the Nez Perce were overtaken by Colonel Nelson Miles in Bear Paw Mountain, Montana. The 418 Nez Perce who surrendered, including women and children, were taken prisoner and sent by train to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Chief Joseph’s famous words upon surrender to General Howard on October 5, 1877 were captured by Charles Erskine Scott Wood, who was party to the negotiations with the Nez Perce. Arthur Chapman, who was married to a Nez Perce woman and fluent in the Nez Perce language, was the interpreter who later accompanied Joseph: “Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. I will fight no more forever! Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before—I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Too-hul-hul-sit is dead. Looking Glass is dead. He-who-led-the-young-men-in-battle is dead. The chiefs are all dead. It is the young men now who say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ My little daughter has run away upon the prairie. I do not know where to find her-perhaps I shall find her too among the dead. It is cold and we have no fire; no blankets. Our little children are crying for food but we have none to give. Hear me, my chiefs. From where the sun now stands, Joseph will fight no more forever.”[30] Chief Joseph appealed to the federal government several times. He spoke at Lincoln Hall in Washington, D.C., to a receptive audience including President Rutherford Hayes. The speech, “An Indian’s View of Indian Affairs in 1879,” gave an interpretation of “equal protection of the law”, as described in the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, and as it should have applied to the Nez Perce: “If the white man wants to live in peace with the Indian he can live in peace. There need be no trouble. Treat all men alike. Give them the same law. Give them all an even chance to live and grow. All men were made by the same Great Spirit Chief…Let me be a free man-free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself—and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty.”[31] A charismatic leader, Chief Joseph became an international sensation when he resisted forced removal to the Nez Perce reservation in Idaho. The Nez Perce War seemed wrong to many, and Joseph insisted, “It is still our land. It may never again be our home, but my father still sleeps there, and I love it as I love my mother.” Nez Perce prisoners were exiled to Oklahoma in the Quapaw Reservation and not allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest until 1885 where they resettled at the Colville Reservation. The United States government had forcibly and violently relocated most of the Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest to reservations by 1880. While the period of disease, warfare, extermination, and forced migrations was coming to an end, the words of Republican Senator William John McConnell in his 1913 book Early History of Idaho sum up the tragic reality of Manifest Destiny in the Pacific Northwest: “As the crickets and jack rabbits sometimes over-run and destroy the crops in these valleys today, without asking leave, so we of the Anglo-Saxon race in those days over-ran and destroyed the hunting grounds of the original owners, and without asking leave took forcible possession thereof. Not having the time to spare from our other pursuits to sufficiently punish the Indians for presuming to bar our progress, we appealed to the government to support us in holding the country we had entered.”