5 Statehood: Constitutional Exclusions and the Civil War

During the Civil War, racial anxieties affected the nation when Oregon became a state. Many pioneers who came to Oregon originated from border states split over slavery and bitterly divided between Democrats and Republicans and their allegiance to the Union and Confederacy. African Americans had first arrived in Oregon in 1788 and Portland in 1850. The migrations of the 1840s and 1850s established a black presence in Oregon. There were only 150 black residents during this era, and African Americans lived in fourteen of the nineteen counties of Oregon. They were involved in an array of occupations in the early Industrial Revolution, including agriculture, business, mining, seafaring, personal service and domestic labor.[1]

The Civil War and its Effects

Throughout the Northwest the Civil War was an intense, immediate, and ongoing concern. Bitter debates over states’ rights, slavery, and emancipation turned neighbor against neighbor. Between the years 1840 and 1860, the African-American population in Oregon never rose above one percent, and yet the issues of slavery and free blacks dominated the political debates of the period and defined the Civil War experience in Oregon. The communities of southern Oregon migrated from the upper South (cis-Appalachia) and the Ohio River Valley, from states like Missouri and Kentucky, and the southern tiers of Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana. Many of the white residents of these states escaped the economic and political domination of the aristocratic slaveholders. They disliked slavery, but harbored fear towards blacks.

Whites of the Old Northwest (the Ohio River Valley) shared the idea that blacks were not only racially inferior, but a threat to free white society. Settlers from these regions held similar negative views toward the sovereign rights of Native Americans. They thought Native Americans impeded their access to free land, and sympathized with the political platform of the Confederates who emphasized small government and states’ rights. Named after Democratic heroes President Andrew Jackson and Senator Stephen Douglas, Republicans of Oregon started to identify Douglas, Jackson, and Josephine counties as the “Dixie of Oregon.”[2] Democrats and Confederates were intent on establishing a Jacksonian reign of the “common (white) man” in the Northwest. Settlers from New England populated the northern counties of the Willamette Valley, giving a political contrast to the southern part of the state.

Early settlers also sought to prevent an unfair competitive labor market from being established in Oregon. A farmer from Missouri during the antebellum period in 1844 stated, “Unless a man keeps [slaves] he has no even chance; he cannot compete with the man who does…I’m going to Oregon where there’ll be no slaves, and we’ll all start even.” Slavery controlled the labor market in the South dominated by plantation economies and involuntary servitude. White emigrants from the south shaped labor markets in the American West cornering the profits to be shared only by themselves.

In addition to economic concerns, white settlers brought their prejudices with them, including the threat of whipping of black people who tried to enter the state. Many settlers of Oregon wanted to bar blacks from entering the territory partly due to racial antipathy and fearing their competition in job markets. The threat of blacks uniting with Natives in revolt was a rampant fear among whites. Ultimately, federal constitutional amendments overturned Oregon state laws that barred blacks from residing in the state, but those laws remained in the books until 1926. In a similar distortion of states’ rights, the state of Oregon did not re-ratify the Fourteenth Amendment (equal protection of the law) until 1973 after it had been rescinded in 1868, and the Fifteenth Amendment, the right to vote, was not ratified until 1959.

The first exclusion law was proposed and passed on June 18, 1844, and it required all blacks to leave the territory within three years (males had two years to leave, and women had three). Slave holders were required to free their slaves, and those freed slaves could not remain in the state. Any African-American found in violation of this law were subjected to a Lash Law, a form of corporeal punishment by public whipping, and was to be repeated after six months if they refused to leave.[3] Voters rescinded the law in 1845.

Peter Burnett

Oregon pioneers like Peter Burnett from Missouri helped create the 1844 racist exclusion law. “The object is to keep clear of that most troublesome class of population. We are in a new world, under the most favorable circumstances and we wish to avoid most of those evils that have so much afflicted the United States and other countries.”[4] His letters were published in Missouri newspapers, and his descriptions of Oregon encouraged many others to move west. Burnett came to Oregon with his family in 1843 and settled on a farm near Hillsboro, where he eventually represented the district of Tualatin on the Legislative Committee and in 1844 introduced the exclusion law.

Burnett considered emigration to be a privilege for whites rather than a right for all; therefore, freedom of travel and commerce was to be a protected space of prosperity for whites. This stance was envisioned by the “Free Soil” principles introduced into the settlement of the American West. Based on historical and judicial precedent, Burnett felt denial of these freedoms could be achieved without denying people of color their constitutional rights. Since blacks were not permitted to vote, he argued, it was better to deny them residence as well since they would have no motive for self-improvement.[5] Burnett is correct about constitutional protections as of 1844; the amendments that abolished slavery and offered equal protection of the law didn’t exist yet.

A minority of citizens who detested the Exclusion Law signed petitions in favor of repealing the law. The pioneer Jesse Applegate who founded the Applegate Trail that helped settlers arrive into southern Oregon from California was opposed to the law. Applegate came to Oregon in 1843 and was elected to the Legislative Committee where he supported the repeal of the Exclusion Law of 1844.[6] He also opposed slavery but still used slave labor for his agricultural fields when labor was scarce. Applegate was a Whig Republican who showed no interest in politics or office holding but helped organize the Republican Party in Oregon.

Oregon Divided Over Slavery

Oregon newspapers were divided over the issue of slavery. On the Democratic side of the political aisle, the Table Rock Sentinel of Jacksonville was proslavery, and wanted property ownership in slaves to be constitutionally protected as well as the Occidental Messenger of Corvallis declared, “We have not begun to fight” for the protection of slavery in the state constitution. William T’Vault was a Tennessee-born attorney and editor of the Table Rock Sentinel. He intended to form a “slavery tolerant Territory of Jackson” out of the mining regions of the Siskiyou Mountains of Oregon and California. The Oregonian of Portland and the Oregon Argus of Oregon City editorialized on the issue of slavery in line with more mainstream Republican Party views and felt personal property in the form of slavery was unethical and should not be a right protected by the State. The Oregon Argus looked at the proposal of slavery as “a huge viper, with poisonous fangs at its head, a legion of legs in its belly and a deadly sting in its tail.”

The Oregonian signed an 1851 petition requesting repeal of the 1849 Exclusion Act. They wanted to “call attention to the severity of the law and the injustice often resulting from the enforcement of it.”[7] At the 1857 Oregon Constitutional Convention, slavery was anathema to most delegates, but so too was the idea of racial equality. The Convention adhered to the popular sovereignty doctrine which put the decision in the hands of Oregon voters. Oregon Democrats were united in their opposition to African Americans, and the great majority believed that slavery did not belong in Oregon. The state of Oregon was neither dominated by proslavery advocates or abolitionists. Many Oregonians detested slavery but not on moral grounds. Instead, African-Americans would be seen as economic competitors and social intruders.

Exclusion Laws

Oregon created three exclusion laws in 1844, 1849, and 1857. While not widely enforced, these discriminatory laws, along with restrictions on land ownership and voting, help explain why there were so few African-Americans in Oregon. Slavery existed in Oregon in parts of the Willamette and Yamhill Valleys, even though it was prohibited by law. Exclusion laws designed to prevent black people from coming to Oregon were passed twice during the 1840s, considered several more times, and finally passed as part of the state constitution in 1857. In 1860, the year after Oregon achieved statehood, its black population was just 128 in a total population of 52,465, and those numbers included several dozen enslaved African Americans.

An exclusion clause to be included in the Oregon State Constitution was approved by popular vote on November 9, 1857 and remained a part of the state constitution until 1926, long after nullification by the Civil War amendments to the federal constitution. The Exclusion Clause stated:

“No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein; and the legislative assembly shall provide by penal laws for the removal by public officers of all such negroes and mulattoes, and for their effectual exclusion from the state, and for the punishment of persons who shall bring them into the state, or employ or harbor them.”

Oregon’s exclusion laws entailed barring African-Americans from entering Oregon, even on seafaring vessels. There was a $500 fine for any negligent ship owner. Any black or mixed race person in violation of the law was to be arrested and ordered to leave. Exclusion laws similar to those enacted in Oregon were passed in Indiana and Illinois and were considered, though never passed, in Ohio. Settlers who brought racist attitudes with them across the plains saw legal restrictions as the best solution to the problem.

On the Oregon Trail, enslaved Africans traveled with their owner’s families, and census takers listed them as “servants” since there was a territorial prohibition on slavery. Samuel Thurston, delegate to the Congress who breathed life into the Donation Land Claim Act, repeated the same fears of collusion by people of color in his efforts to secure the restriction of land grants to white people unleashing a pattern of realty laws favoring whites for several decades in Oregon.

“The first legislative assembly…passed another law against the introduction of free negroes. This is a question of life and death to us in Oregon, and of money to this Government. The negroes associate with the Indians and intermarry, and, if their free ingress is encouraged or allowed, there would a relationship spring up between them and the different tribes, and a mixed race would ensure inimical to the whites; and the Indians being led on by the negro who is better acquainted with the customs, language and manners of the whites than the Indian these savages would become much more formidable than they otherwise would and long and bloody wars would be the fruits of the commingling of the races. It is the principle of self-preservation that justifies the action of the Oregon legislature.”

Petitions were filed by several black residents of Oregon requesting the repeal of the Exclusion Laws, but all were defeated. One state legislator sponsored another exclusion law to replace the 1849 exclusion law, claiming black settlers had no right to stay in Oregon because they had taken no part in settling the area and displacing the native population. Aside from the illegitimacy of such a litmus test for settling, there is an overwhelming amount of evidence that proves this was false. George Washington Bush was an important black pioneer on the Oregon Trail and Moses Harris was a black mountain man and wagon train guide who had escorted the Whitman and Spaulding families. Harris also assisted stranded settlers in Central Oregon and the Oregon Desert. Clearly, people of color assisted in the settlement of Oregon, but proponents chose to ignore the evidence. Opponents of the bill saw the legislation as endangering a source of cheap labor and suggested there would be a lack of menial laborers if it was passed. “What negroes we have in the country it is conceded are law abiding, peaceable, and they are not sufficiently numerous to supply the barber’s shops and kitchens of the towns…If a man wants his boots blacked, he must do it himself.”[8] To some Oregon lawmakers, that scenario seemed beneath them.

In the end, the exclusion clause was overwhelmingly approved by voters, with 8,640 in favor and 1,081 opposed. Oregon became the only state admitted into the union with such a clause in its constitution. A slavery clause was rejected during this time as well. There were 2,645 who voted in favor of slavery and 7,727 who were opposed to permitting slavery in Oregon. If slavery had been voted for by the people, such a clause would have stated:

“Persons lawfully held as slaves in any state, territory or district of the United States under the laws thereof, may be brought into this state; and such slaves and their descendants may be held as slaves within this state and shall not be emancipated without the consent of their owners.”[9]

Jacob Vanderpool

According to the census taken in Oregon in 1850, 207 people were identified as black or mulatto. Of this number, three-quarters were actually Hawaiians or mixed ancestry Indians, as the census takers tended to put all non-whites in the same category. There were only fifty-four black people included in the census of 1850. The first and only successful attempt to enforce a racial exclusion law was made against a former sailor, Jacob Vanderpool, in 1851, who was an Afro-Caribbean business owner near Salem. Vanderpool owned a saloon, restaurant, and boarding house. His neighbor, Theophilus Magruder, manager of the City Hotel of Oregon City in 1847, was also a proprietor of the Main Street House in Oregon City in 1851. Magruder sued Vanderpool in court for “being black in Oregon”, and was arrested and jailed. Perhaps Magruder could not face a healthy competitive marketplace when a man of color challenged his business interests. Vanderpool’s defense lawyer argued that the law was unconstitutional since it had not been legally approved by the legislature. The prosecution offered three witnesses who gave vague testimonies. The following day, Judge Thomas Nelson ordered Vanderpool to leave Oregon within thirty days. The Oregon Spectator of Oregon City celebrated the outcome as a victory for law and order: “A decision was called for respecting the enforcement of that law; [Nelson] decided that the statute should be immediately enforced and that the negro shall be banished forth with from the Territory.”[10]

Slavery in Oregon

Former slaves who resided in Oregon resisted enslavement through the legal process or left the state. Chief Justice of the Territorial Supreme Court George Williams presided over a case in 1853 involving Nathaniel Ford, who refused to manumit (release from slavery) four of the children of Robin and Polly Holmes, who were freed in 1850. Holmes demanded the return of their children, but Ford refused and threatened to return the entire family back to Missouri as slaves. Holmes proceeded to file a habeas corpus lawsuit against Ford for holding his children illegally. Williams, a “Free Soil” Democrat appointed by President Franklin Pierce, opined slavery could not exist in Oregon unless there was specific legislation to protect it:

“Whether or not slaveholders could carry their slaves into the territories and hold them there as property had become a burning question, and my predecessors in office, for reason best known to themselves, had declined to hear the case. I so held that without some positive legislative [act] establishing slavery here, it did not and could not exist here in Oregon, and I awarded the colored people their freedom. Where slavery does not legally exist, [slaves] are free.”[11]

The children could have been sent back to Missouri under the Fugitive Slave Law that was passed by the U.S. Congress on September 18, 1850. Holmes v. Ford was the final judicial attempt to maintain slavery by proslavery settlers in Oregon. There were many proslavery men who found Williams’s decision to be very distasteful. The polarization of beliefs on slavery that split the national Democratic Party took more time to develop in Oregon, but as it developed, the local party fostered a planned policy of silence on slavery in order to maintain party unity. It was strengthened by the presence of Joseph Lane, the appointed territorial governor and a Democrat himself, who had adapted himself to local interests. Lane was an honored veteran of the Mexican War which was a battle premised upon the expansion of slavery, the cotton industry, and plantation economy in Texas.[12] Well-known as a southerner, he was sympathetic to slave-owning interests, but in the 1850s, he remained silent on the subject of slavery.

In June 1855, an anti-slavery convention was held in Albany, Oregon. During the convention, the group adopted eight resolutions that condemned the Fugitive Slave Law and the repeal of the Dred Scott Decision. They vowed to fight any attempt to introduce slavery into Oregon. The Oregon Statesman was particularly vicious in its outlook supporting the cause of slavery. The newspaper condemned people in Oregon working for the civil rights of black people in the state, and referred to them as abolitionists. They reprinted a racist diatribe from the Examiner of Richmond, Virginia that put black enfranchisement into the realm of animals being given a political voice in America:

“Their assertions that Negroes are entitled to approach our polls to sit in our courts to places in our Legislature are not more rational than a demand upon them that they let all adult bulls vote at their polls all capable goats enjoy a chance at their ermine, all asses the privilege of running for their General Assemblies and all swine for their seats in Congress.”[13]

Asahel Bush, the editor of the Oregon Statesman, opposed slavery in Oregon, but held the racist view popular among the Democratic party that slavery was a way for African people to “better” their economic and social position. He held racially inflammatory views about cultural plurality and the inclusion of African-American people in the state of Oregon: “We have but few n*****s here, but quite as many of that class as we wish to ever see.” He was opposed to white people bringing blacks into the state, and sought to prevent blacks from buying real estate, bringing a suit to court, or enforcing any contracts or agreements. Essentially, this is what Jim Crow policies would look like after the Civil War. “We are for a free state in Oregon,” Bush wrote.[14] In his vision, a free state was monochromatic in terms of political power and influence, and this traditional view would persist after the Civil War among some Oregonians.

MATTHEW DEADY, GEORGE WILLIAMS AND SLAVERY

Oregon statehood occurred in the midst of the judicial turmoil that followed the Dred Scott Decision in March 1857. In the landmark case, Chief Justice Roger Taney of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Congress had no power to exclude slavery from territories like Oregon and by rule of popular sovereignty, the people could choose slavery through the vote. Oregon Supreme Court Judge Matthew Deady was elected President of the Oregon Constitutional Convention that same year. Deady initially was an advocate for slavery, and considered popular sovereignty a constitutional right of the people. Popular sovereignty concerned the settlement of western states and how the people could decide by vote to include or exclude slavery in their state constitutions.

Joseph Lane, who served as territorial governor of Oregon at the time, supported the idea of popular sovereignty, which for pro-slavery advocates seemed a politically safer route by freeing government authority from the onus of creating prohibitive legislation regarding slavery. In other words, those voting in favor of allowing slavery in Oregon saw it as a defensible stance. “Our motto was, in the late canvass, and in our platform, and it is the true principle of the Kansas-Nebraska bill, ‘leave it to the people.’”[15]

The idea of slaves as a form of personal property was debatable in the political divide during the years leading up to the Civil War. Judge Deady insisted that slavery was an inviolable right of property ownership, and a transferable right held by individuals. Deady asked, “If a citizen of Virginia can lawfully own a Negro…then I as a citizen of Oregon can obtain the same right of property in this Negro…and am entitled to the protection of the Government in Oregon as in Virginia.”[16]

Lane and his political constituencies would support the constitutional exclusions of a white free state. Justice George Williams submitted his legal perspective on the issue in a racially inflammatory piece called “The Free-State Letter” which was addressed to Asahel Bush, the editor of the Oregon Statesman. Williams warned that Oregon should “keep as clear as possible of negroes,” slave or free. According to his opinion, slave labor was involuntary, and black people were lazy and would degrade the labor market. “One free white man is worth more than two negro slaves in the cultivation of the soil,” he said. He framed the issue of race in the establishment of Oregon as a “free labor” state that would not be prone to the same troubles the Southern states had pulled themselves into through the “economic necessity” of slavery. Williams’ racial sympathies nevertheless were quite clear, especially concerning his wishes to keep Oregon as white as possible, “consecrate Oregon to the use of the white man, and exclude the Negro, Chinaman, and every race of that character.”[17]

Williams shared the prevailing sentiments among Oregon Democrats that disliked abolitionism and the idea of black equality. “Negroes are naturally lazy, and as slaves actuated by fear of the whip are only interested in doing enough to avoid punishment.”[18] In the letter, he states he has “no objections to local slavery. I do not reproach the slaveholders of the South for holding slaves. I consider them as high-minded, honorable and human a class of men as can be found in the world, and throughout the slavery agitation have contended they were ‘more sinned against than sinning.’[19] While playing to the political base of the Democratic Party of Oregon in his “Free-State Letter,” Williams conjured the fears brought on during the critical year of 1857, when the Dred Scott decision negated Congress’s power to control slavery in the American states. The vision of a “Free Soil” American West and the viability of the Republican Party were all critically in jeopardy. “Can Oregon, with her great claims, present and prospective, upon the government, afford to throw away the friendship of the North-the overruling power of the nation-for the sake of slavery?”[20]

Bush feared the political consequences of slavery after reading Williams’ “Free-State Letter,” calling it “an impossible institution for Oregon.” Bush wrote that “the African is destined to be the servant and subordinate of the superior white race…that the wisdom of man has not yet devised a system under which the negro is as well off as he is under that of American slavery.” Former governor of Oregon Oswald West viewed Bush as anti-democratic, “through his sagacity and the power of his pen, was to become dictator in Oregon politics for many years.”[21]

Oregon would enshrine the exclusion of African-Americans from living in the state in the state constitution. Jesse Applegate left the Oregon Constitutional Convention in disgust and wrote in a letter to Matthew Deady, “The free Negro section is perfectly abominable, and it is hard to realize that men having hearts and consciences, some of them today in the front ranks of the defenders of human rights, could be led so far by party prejudice as to put such an article in the frame of a government intended to be free and just.”

Barely two months after voters rejected slavery in 1857, bills to protect slave property were proposed in Oregon. William Allen, a Democrat from Yamhill County, introduced a resolution:

“It has been decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that Congress has no power to prohibit the introduction of slavery into the Territory…slavery is tolerated by the Constitution of the United States; Therefore, Resolved, that the Chair appoint a committee of three, to report what legislation is necessary to protect the rights of persons holding slaves in this Territory.”

In defense of his resolution, he stated:

“I don’t see any reason why we should not have laws protecting slavery. There are slaves here, but no laws to regulate or protect this kind of property. There are some in Benton, Lane, Polk, Yamhill, and I know not how many other counties. Slavery property is here! It then becomes our duty to protect that property as recognized by the constitution of the United States.”[22]

Several members of the legislature admitted they knew people who owned slaves, and they thought slaveholders should have protections. Former governors of Oregon John Whiteaker and Lafayette Grover, both Democrats, were outspoken in their support of slavery. It indicates there was a proslavery faction in Oregon politics that refused to admit defeat.

Governor John Whiteaker and The Civil War

“Have a care that in freeing the Negro you do not enslave the white man,” was one of Whiteaker’s guiding principles as Oregon’s first governor. As America descended into the Civil War, his political opponents used his anti-Union sympathies against him. Governor John Whiteaker, whose anti-immigrant sentiments were well known, said Union meetings being held throughout the state were causing disorder and maintained that those opposed to the war were not disloyal. He was a Southerner who believed in state supremacy and in the divine right of slavery. He issued a manifesto warning people against getting mixed up in the political divisions of the Civil War, declaring that the Southern states had rights that should be respected, and interference from the state would not be tolerated. Judge Matthew Deady, once said of Whiteaker, “Old Whit is a good specimen of a sturdy, frontier farmer man, formed by a cross between Illinois and Missouri, with a remote dash of a something farther Down East. Although wrong in the head in politics, he is honest and right in the heart.”

Whiteaker also sought to purge the Chinese population from Oregon and prevent others from coming into the state. “An act to tax and protect Chinamen mining in Oregon,” was approved in 1860 by the Oregon House and signed into law by the governor, and it levied a $50 per month tax against an individual man of Chinese descent. The law was designed to curtail immigration of Chinese miners and laborers in the state, and encourage their removal. Whiteaker and the Democrats of Oregon wanted to curb cheap labor in the mines, and claimed the law was intended to prevent people from exploiting the Chinese. State officials believed placing a poll tax on Chinese miners would guarantee their protection, but this was unenforceable. With a large number of Chinese immigrants working on the railroads, mines and other heavy labor, many Oregonians were opposed to their presence. Abuse of Chinese miners was at times impossible to curb or police effectively.

In actuality, this legislation was designed to limit the Chinese presence in Oregon mines. The law stated, “No Chinaman shall mine in this state unless licensed to do so as provided by this act.” Section II of the law also stated, “Every Chinaman engaged in mining in this state shall pay for such mining privilege the sum of two-dollar tax per month.” Included within these provisions were exclusion clauses focused on Native Hawaiians or “Kanakas”: “All Chinamen or Kanakas engaged in livestock trade or trading in general shall pay for such a privilege at a rate of fifty dollars a month.” The Chinese also had to pay a quarterly poll tax of six dollars. If they did not pay the poll tax, license fee, or prohibitive business tax, the sheriff had “permission to seize all the Chinamen’s property and sell [it] at a public sale to the highest bidder at one hour’s notice.” Mine employers had to make sure the laborers paid their fees. The State Treasury got 10 percent of the gross revenue collected, the sheriff skimmed 15 percent, the clerk or auditor got 15 percent. The rest of the fees and taxes went to the counties where Chinese people were working or residing. The licensing fees and poll taxes—as elsewhere in the United States, including California—involved a tremendous network of financial graft and stuffing the pockets of government officials.[23]

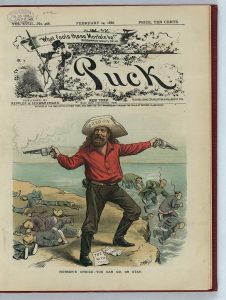

Knights of the Golden Circle

Spurred by the increase of abolitionism during the tumultuous 1850s, the Knights of the Golden Circle an underground national society, and a precursor to the Ku Klux Klan was established. The Golden Circle had a plan to create a separate territory called the Pacific Coast republic during the Civil War, which would annex a “golden circle” of territories in Mexico, Central America, Confederate States of America, and the Caribbean as slave states. Their object was to “put down the present administration [Lincoln}, to resist the draft if an attempt should be made to enforce it, and to improve the first favorable opportunity of erecting a Pacific Republic.”[24] Between 1863 and 1864, there were roughly 2,500 members in at least ten groups in various towns in Oregon, including Portland, Salem, Scio, Albany, Jacksonville, Dallas and Independence. They met at the Cincinnati House in Eola, Oregon, and distinguished members could authenticate their arrival through secret handshakes, “give two shakes downward”, or “stroked the mustache twice with the first two fingers against the thumb.” Members, as part of their duties as a paramilitary group, were required to be armed with a least 40 rounds of ammunition at all times.

Joseph Lane was rumored to have been a part of this organization along with southern Oregon Democrats, who openly supported the Confederacy and suggested the North surrender. Lane returned from Washington D.C. in disgrace, accused of smuggling guns for the Knights. The Portland Oregonian exposed the organization and its members, some of whom were running for public office. In the vision of the Knights, universal voting rights would be discarded and manual labor would be provided by Chinese and Hawaiian immigrants, and slaves would continue to be imported from Africa and remain in slavery.

CHINESE IMMIGRANTS

After Oregon achieved statehood in 1859, the plight of Chinese immigrants in the state of Oregon would overlap with the African-American experience. Racial hostility was vented toward the new arrivals from mainland China. It was particularly pronounced in cities like Portland, which had the second-highest population of Chinese immigrants in the country, behind San Francisco. A House bill was prompted by a petition signed by 293 residents of Multnomah County, where Portland is located, who complained that black and Chinese people were becoming an intolerable nuisance, crowding in and taking over jobs that poor whites had held. The petition stated, “We ask to provide by law for the removal of the negroes and such provisions in reference to Chinamen as to cause them to prefer some other country to ours.” The Chinese immigrant community would be the targeted by nativist rhetoric and animosity producing populist anger and hysteria toward the Asian newcomers.

The political and economic situation in mainland China was in shambles due to British imperial exploits from the Opium Wars. As early as the 1850s, Chinese laborers, mostly from Guangdong province on the coast of southern China, settled in the southern and eastern parts of the Oregon Territory and northern California to mine gold. Chinese men built the railroads of Oregon, and they composed the largest percentage of cannery workers in Astoria. Chinese laborers, predominately men, were welcomed by many due to their willingness to work for low wages. By 1890, males constituted 95 percent of the 9,540 Chinese immigrants who lived in Oregon. Many factors inhibited women’s immigration. Women were discouraged from emigrating because of rumors that the United States was a dangerous place with depraved people. The passage fees on ships were exorbitant and the conditions on board were ghastly with hundreds overcrowded in the steerage class of the ships. Some women had been promised jobs or husbands that never materialized, and the ratio of men to women made them vulnerable to sexual exploitation. Some could only find work as prostitutes in Chinatown brothels.

The two major ports for disembarkation for Chinese immigrants were Portland and San Francisco. They usually borrowed forty dollars from hiring agents in the U.S. to pay for their passage across the Pacific. The money would be deducted from their wages, a process known as the credit-ticket system. They often came alone, leaving their families behind. Chinese people have been in Portland since its founding, encouraging many others to arrive in the 1850s. Immigration from Hong Kong to Portland was in full swing in 1868 to meet a demand for railroad workers. In 1882, the last year of unrestricted immigration, 5,000 Chinese arrived in Portland by ship. By 1890, there were 4,740 Chinese people and 20 Japanese people living in the Portland area.

There was a shortage of cheap labor until the Panic of 1873 and land speculation by railroad companies, among other things, put a massive strain on bank reserves triggering an economic depression. Many Chinese who had come to mine for gold in California moved up to Portland or other areas in the Pacific Northwest, where they took up employment as cooks or offered laundry services. Some became gardeners for the wealthier residents. For the Oregonians who opposed Chinese immigration to the U.S., the newcomers were seen as an impoverished class that was the object of racial stereotyping based on assumed lawlessness, gang violence, addiction to opium, and the proliferation of prostitution in Chinese women. Racial antagonism towards the Chinese people was common. Some of the stereotyped claims against the Chinese entailed that they did not make long-term contributions to America and they practiced slave labor. There was also a distaste for Chinese religion and customs. Chinese immigrants were willing to settle for lower wages than white laborers in Oregon, thus disrupting the vision of a free labor market that prioritized white business transactions. Once Chinese men were able to establish themselves with wage-paying work or find wealth in the gold mines of Oregon, they often returned to China or some remained in coastal towns, eastern Oregon, and the Willamette Valley.

ANTI-CHINESE HYSTERIA and MATTHEW DEADY

Fortunately for the Chinese community of Portland, race riots did not explode in Portland as they did in Tacoma, Washington, and Los Angeles. Historians have felt that Judge Matthew Deady played a critical role in providing judicial protections to the Chinese community, which may have staved off the waves of wanton violence that affected other Chinese communities in the American West. In 1871 in Los Angeles, California, nineteen Chinese were murdered, and seventeen of which were lynched in race riots. The Morning Oregonian of February 8, 1886, called the anti-Chinese violence in Tacoma and Seattle “a gross and extreme outrage.” The editor of the Oregonian, Harvey Scott, stood in partial defense of Chinese people:

“To attempt to expel the Chinese of Portland by force would be mere madness. Such a number can only go by gradual departure…As the Oregonian has so often said, the Chinese when they can no longer find work will rapidly take their leave. The Chinese came here in pursuance of [Burlingame] treaty and while they are here are entitled to all protection of the laws [emphasis added].” [25]

One of the strongest judicial advocates of the Chinese community in Oregon was Judge Matthew Deady, who defended the rights of the Chinese people according to the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. Deady is the same man who actively promoted the exclusion of free blacks and Chinese from Oregon at the Oregon Constitutional Convention in 1857 and believed that the right to vote should only be held to “pure white men.” “The negro was superior to the Chinaman, and would be more useful.”[26] During the course of the Civil War, Deady experienced a substantive political and legal transformation. In the aftermath of the Civil War, he denounced the Confederacy as treasonous and wholeheartedly supported the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the US Constitution, providing for the emancipation of slaves, full civil rights to freedmen, and the right to vote for all men. Deady’s judicial decisions shielded innocent and vulnerable people from harassment, discrimination, and violence. He invoked the Fourteenth Amendment and the equal protection of the law particularly with Chinese Oregonians. This is stunning considering the Oregon legislature’s rescission of its initial ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868. Democrats in the Oregon legislature seized upon the intertwined issues of interracial marriage and ratification of the 14th Amendment and successfully voted for its rescission.[27]

However, the Oregon Constitution in 1859 forbade any “Chinaman, not a resident of the State at the adoption of this Constitution” from holding “any real estate, or mining claim, or work[ing] any mining claim therein.” Local mining districts also passed discriminatory laws against the Chinese. One was passed in the John Day mining district in 1862: “No Asiatic shall be allowed to mine in this district.” It is apparent that these laws were not enforced, since Chinese bought and sold mining claims.[28]

There was a lot of fury over the Burlingame Treaty of 1868, which provided for “free and unrestricted immigration between China and the United States.” The Burlingame Treaty also entailed opening Chinese retail markets to American exports, and served to attract more Chinese laborers, still much in demand to work on the railroads. The treaty included security guarantees for immigrants, but denied them the right to become naturalized citizens, including a restriction on Americans seeking Chinese citizenship.

Racial animosity boiled over in places like Oregon against the Chinese people. Raids, beatings, and arson fires were common in the Chinese experience in Oregon. Conflicts over labor and its accompanied nativist hysteria was the main culprit. Public animosity was inflamed by politicians such as Sylvester Pennoyer, who supported the Confederacy and slavery, ran for governor, and won on an anti-Chinese populist plank. Oregon State Senator John H. Mitchell, who accepted political graft from a land fraud scheme, gave demagogic speeches on the Senate floor against the Chinese community.

The Oregon City Woolen Mill employed many Chinese among its workers. The white workers struck to force the mill to discharge the Chinese, but the strikers were replaced by more Chinese, who were met with violence. When the Panic of 1873 devolved into economic depression, there was a more intense wave of intense anti-Chinese hysteria. The flames of hatred were fanned by working class unemployment, and the perceived threat of Chinese workers to their interests.

CHINESE EXCLUSION

The United States was unprepared to provide protection to Chinese workers—and unwilling. Chinese people were being jailed on made-up charges, and town ordinances banished the freedom of movement for the Chinese in American cities. Under intense pressure from western politicians, President Rutherford Hayes negotiated with the Chinese a new immigration treaty. This was the Angell Treaty of 1880, which unilaterally restricted Chinese immigration, and the Chinese government received protections for its citizens on American soil. Congress implemented the treaty by enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred further immigration of Chinese laborers, although it permitted those in the country to remain. The exclusion did not include students, professionals, or merchants. Many of the worst outrages against the Chinese occurred after 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act was given an extended life for another ten years by President Chester A. Arthur. It was the first national act that restricted immigration based on race and national origin. The Chinese Exclusion Act failed to protect the 132,000 Chinese who remained on American soil, removing the protections of the Angell Treaty.

Portland mayor W. S. Newbury exemplified the populist feeling against the Chinese people of Portland on the concerns of Chinese laborers pushing whites out of the labor market:

“I feel it is our duty and mine, on all proper occasions, to give expression to the sentiment which is becoming so universal on the coast, of opposition to further Chinese immigration to this country. There is a deep seated, growing feeling of hostility to them in the minds of the working class of this community which cannot be overlooked or go unheeded with safety to the future…Law and Order must and should be maintained. The true method would be to remove the cause…In the meantime, allow no Chinaman to be employed or any contract let by the city. Let the memorial show in the infamous state of slavery that exists among them, their filthy and indecent practices and habits; how the rich companies own not only the labor of the men but the bodies of the women.”[29]

Portland’s Chinatown was located along Second Avenue between Pine and Taylor Streets. Chinese ambivalence or antipathy to assimilation made them a target of American animosity. Most of the Chinese stayed in Chinatown because they were subjected to harassment, mostly from young white males, if they travelled elsewhere. In sections of Portland, businesses had signs in their windows that advertised that they employed no Chinese people, and they catered to “white trade only”.

THE KNIGHTS OF LABOR AND CHINESE IMMIGRANTS

The nation was suffering from an economic depression, growing labor militancy, and a nationwide debate over free labor while the Northwest experienced rampant anti-Chinese fervor. Most of the anti-Chinese rioters were transients living in the city. Railroad workers fanned the flames of racial animosity, anti-socialism, and the Chinese. Daniel Cronin a leader of the anti-Chinese crusade in Portland convinced many of the unemployed affected by the depression of 1873 to join his vigilante group. Cronin used his connection with the Knights of Labor to achieve legitimacy for his cause. He, along with B. G. Haskell, came down from Seattle to Portland in 1886 to force the Chinese population to depart from the city. In a speech he made in east Portland, he stated, “You must drive out the Chinese, peaceably if you can, forcibly if you must; if necessary, shed blood.”

Among state officials, Senator John Mitchell, a Republican from Oregon, fanned the flames of populist hysteria by stating the Chinese Exclusion Act had not gone far enough. He had supported the ouster of Portland’s Chinese during the 1886 agitation. Mitchell was quoted as arguing, “If he had his will, he would make exclusion apply not only to the four hundred million Chinamen in China, but to those now in the United States.”

The week after Cronin’s speech, an anti-Chinese demonstration with torches and music moved along the streets of Portland with about 3,500 people shouting, “The Chinese must go!” On that same day, members of the Knights of Labor and the Anti-Coolie League in Oregon City forcibly removed Chinese men sleeping at the Washington Hotel, and between forty and fifty-five workers were corralled onto a steamboat in Oregon City and sent to Portland. Twelve men were arrested in association with the crime, one being Nathan Baker, who was associated with the Knights of Labor. The Knights notoriously excluded Asians from their union throughout the nation, and spearheaded the expulsion of the Chinese. They were one of the main moving forces behind the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. They wove together the social ills of unemployment and anti-Chinese prejudice.

THE LEGAL DEFENSE OF THE CHINESE PEOPLE OF OREGON

Many Jewish-owned businesses and influential leaders of Portland did not resort to racist discrimination. Historically they had been targeted as outcasts in American and European societies and held empathetic views towards minorities who were oppressed like themselves. In June 1873, Portland Mayor Bernard Goldsmith vetoed a city council effort to prevent Chinese laborers from being employed on city contracts. He, along with previous mayor Phillip Wasserman, cited the recently passed Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution and the Burlingame Treaty with China in defense of its Chinese residents. In 1886, Goldsmith and Wasserman joined others as special deputies to successfully defend the Chinese quarter from mobs threatening to expel them from Portland. These two men were more concerned about the civil liberties of the Chinese and other minorities than their colleagues.

In 1884, the Portland City Council passed an ordinance purporting to license and regulate wash houses and public laundries. It was a transparent effort to harass Chinese laundries that required extensive record keeping, sanitation measures, and a quarterly $5 licensing fee. Portland Police convicted laundry proprietor Wan Yin for failing to pay the licensing fee, and petitioned Deady for a writ of habeas corpus (a court order demanding that a public official deliver an imprisoned individual to the court and show a valid reason for that person’s detention). Deady ruled on the fee as a tax and further stated a federal judge’s obligation to protect due process of law under provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment as a bulwark against local oppression and tyranny. The 1888 cases of Ex parte Chin King and Ex parte Chan San Hee demonstrated the barriers to full citizenship experienced by American born, second-generation Chinese women. They were sisters born of immigrant parents in Portland and San Francisco. When they returned from a trip to China in 1888, they were forced to remain on a British ship. The Portland collector of customs insisted they present certain certificates required under the Chinese Exclusion Act. They had no such documents and filed a writ of habeas corpus in the federal district court of Oregon. The sisters argued that as American citizens the Chinese Exclusion Act did not apply to them and they did not need any certificates for re-entry. Judge Deady agreed, finding that the collector had unlawfully detained them in violation of their constitutional rights. As King and Hee had all the privileges and immunities of citizenship, Deady called for their immediate discharge.

In Portland, nearly 200 so-called delegates convened an anti-Chinese “Congress” on February 10, 1886, with the aim of setting a thirty-day deadline for the ouster of all Chinese from Oregon. Portland’s Chinese population at the time was estimated at 4,000. Portland Mayor John Gates joined with state and county authorities to protect Chinese immigrants by organizing a security force of more than 1,000, including 700 volunteers. In February 14, 1886, notice was given that all Chinese must depart from Portland within forty days. The Oregonian stated, “This means riot or it means nothing…Those that are here will be protected of course. They will not be maltreated, looted, ejected from their homes, expelled from the city or murdered.” The editor Harvey Scott went on to defend the Chinese and stated, “[those] who are concerning measures for the expulsion of the Chinese are proposing rebelling against the United states…Portland is a law-abiding city…If they persist the actors will be arrested if possible and if not will be shot to death.”

RISE OF SYLVESTER PENNOYER

An anti-Chinese front was established where Chinese were viewed as pawns of corporations that would deny whites a living wage. Sylvester Pennoyer won the gubernatorial election with the help of labor prejudice and nativist hysteria, and the anti-Chinese issue became the dominant issue in the gubernatorial campaign which helped get him elected. Preceding the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, waves of violence and propaganda came through newspapers portraying the Chinese as an unwanted class in Oregon well before the election of Pennoyer. An advertisement was posted in the Oregonian in 1867 stating,

“We protest as follows against the introduction of Chinese in our midst, either by companies or individuals. Resolved, the introduction of Chinese as laborers or residents has proved a scathing blight upon every town, or hamlet where they have been introduced on this coast. Chinese laborers seen as “totally intolerable”. We cannot regard the introduction of Chinese labor in our midst with the least toleration. We think the Oregon Iron Company should remember the Anglo-Saxon race not the Mongolian, make a market for their iron.”[30]

Another attack against Chinese immigrants happened in the Albina district of Portland at the flour mill. White men disguised themselves by blackening their faces and wearing masks made of sacks with holes for eyes. Three days after the attack at the flour mill, fifty masked and armed men drove 200 Chinese woodcutters out of the Mt. Tabor district and forced them to take the ferry across the Willamette River to Portland’s Chinatown. The Oregonian described the mob as a “ku klux” mob.[31] Chinese merchants were constantly being attacked inside the city of Portland. Chinese laundries had stones thrown through their windows, and one was blown up with dynamite.

Mayor John Gates called for a vigilance committee to protect the Portland Chinese community. During the mass meeting, he called for vigilance against populist-infused racism and violence towards the Chinese community and “to consider the alarming growth of lawlessness in our midst consequent upon the agitation of the question of unlawfully driving out of the country a class of foreigners who are here in pursuance of treaty and are entitled to the protection of the law.” The meeting was taken over by a large anti-Chinese crowd with soon-to-be-elected-governor Pennoyer as its chairman. He issued edicts declaring that “the presence of the Chinese in our state is an unmixed and unmitigated evil.”[32] He also called for a boycott of the Oregonian newspaper for its “pro-Chinese sentiments.” The Oregonian opposed Pennoyer: “[Those] who have known him the longest never knew him to entertain sound opinions on any important public question.”[33] The vigilance meeting was relocated, and Mayor Gates and 1,200 other members of the community vowed to “pledge our means and if necessary our lives” to maintain peace and order to protect the rights of the Chinese people to live and work in the community.[34]

The assailants who had attempted to purge the Chinese from Portland were apprehended, and cases were heard against persons charged with mobbing and driving out the Chinese. Judge Deady gave instructions to a Portland grand jury: “If you find that any of the parties have maltreated, menaced or intimidated the Chinese for the purpose or with the intent to compel or constrain them to leave the country…it will be your duty to present them to the court for trial.”

Deady went on to give an impassioned speech to the jury:

“An evil spirit is abroad in this land—not only here, but everywhere. It tramples down the law of the country and fosters riot and anarchy. Now it is riding on the back of labor… Lawless and irresponsible associations of persons are forming all over the country, claiming the right to impose their opinions upon others, and to dictate for whom they shall work, and whom they shall hire; from whom they shall buy, and to whom they shall sell, and for what price or compensation.”[35]

The perpetrators of this “evil spirit,” Deady continued, were those members of the laboring class who justified violence because “the Chinese are taking the bread out of the mouths of their assailants by working for less wages and living cheaper than the latter can.”[36] The grand jury responded by indicting thirteen persons at a time when few Oregonians considered violence against Chinese people an indictable offense. During Deady’s career on the bench, he would go on to defend Native tribal leaders of Oregon, including the sovereign rights of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce. Years later, in his retirement, he wrote in his diary about his exasperation with the relentless white intrusion on Native lands: “To what manifold uses Indians can be put, and how many uncivilized and unchristianized white men have made their fortunes pretending or attempting to civilize and Christianize them.”[37]

Anti-Chinese agitation figured into the gubernatorial election of 1886. Sylvester Pennoyer, in his inaugural address to the legislative assembly, stated his position quite clearly on the “Chinese Question”:

“The unanimity of the people of Oregon on the undesirability of the presence of the Chinese amongst us was very clearly demonstrated by the fact that both political parties at the last election avowed their hostility to any further immigration of that most undesirable population within our borders. At this stage of our experience in regard to this class of pauper slave labor, no argument need to be used to stimulate the Legislative assembly to exhaust every constitutional means by which to rid the state from the corrupting and paralyzing influence of their presence…procuring their removal from the state…Our state would be rid of their baneful presence and the places they now occupy would be filled with laboring men of our own race and blood.”[38]

Pennoyer felt compelled to address his political base that voted for him. Pennoyer claimed to be a supporter of the common man and attacked foreign immigrants who he claimed were taking away jobs from Oregonians. Pennoyer was an “irascible and intensely independent sort”; Judge Deady referred to him privately as “Sylpester Annoyer.”[39]

Pennoyer exalted the Populist Party as the party of the common man. He was stentorian in his political squabbles with adversaries, and he was zealous about the Chinese Exclusion Act. With expected troubles on the West Coast with Chinese people, President Cleveland sent telegrams to the governors of all western states alerting them to the possibility of trouble. The telegram sent to Pennoyer read, “Apparently reliable reports indicate danger of violence to Chinese when exclusion act takes effect and the President earnestly hopes you will employ all lawful means for their protection in Oregon.” Pennoyer was offended by this advice and wrote back, “Let the President attend to his own business, and I will attend mine.”[40] Pennoyer pressured President Cleveland to extend the life of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and stated the President should be impeached if he couldn’t enforce it.

CHINESE MINERS

By 1870, half the population of Grant County was Chinese, and in 1879, a law was passed forbidding marriage among Chinese immigrants in the hope that it would slow their population growth. The Grant County News went on the offensive and disseminated negative propaganda about the Chinese. The newspaper claimed that Chinese labor was inadequate and incompetent compared to white labor:

The policy of the Union Pacific discharging white hands and filling their places with Chinese should be frowned down all over the state. That company whose lines in Oregon scarcely contain a sound tie or a safe trestle or bridge, will soon be utilizing Chinamen for engineers and conductors on their trains. Plenty of accidents happen on the lines now, but then look out.[41]

Some of the propaganda became intensely violent. The following was printed the same year as the Hells Canyon Massacre in 1887: “The only way to swear a Chinaman so as to get the entire unadulterated truth out of him is to cut off a chicken’s head and swear the Chinaman by this process…As far as getting the truth is concerned, it would have as good effect to cut off the Chinaman’s head, and swear the chicken.”[42]

The people of John Day sabotaged Chinese businesses in eastern Oregon. The Chinese use of opium raised the white people’s ire in the town, who referred to the Chinese as “monkeyed denizens.”[43] At the time, smoking opium was legal. The drug was not prohibited until the Food and Drug Act in 1906. For Chinese people, smoking opium was seen as a harmful social ritual that encouraged addiction. It also provided themselves and white settlers with an escape from the reality of living in a harsh frontier land. Living under the threat of deportation or local violence as well as the poverty they experienced led to suicides. Several incidents of insanity were also observed among Chinese living in this difficult environment, where they were intimidated and bullied.

HELL’S CANYON MASSACRE

The worst act of violence committed by whites against the Chinese in Oregon, in terms of lives lost, was the Hells Canyon Massacre. Thirty-four gold miners were robbed and killed on the Oregon side of Hells Canyon on May 25, 1887. The killers were a gang of rustlers and schoolboys from northeastern Oregon in what is now Wallowa County. Some of them were tried for murder and declared innocent, but the leaders of the crime fled and were never caught. The incident was never fully investigated. All the evidence pointed to a cover-up that lasted for more than a century. Bruce “Blue” Evans, one of the perpetrators of the crime, has his name commemorated on an arch of Wallowa County pioneers in front of the Wallowa County Courthouse in Enterprise, Oregon. The plaque on the commemorative arch was commissioned in 1936, and the truth about Evans was not revealed until a dossier of documents exposing his role in the murders was discovered in 1995.

As the gold fields played out, the Chinese looked for other work. Sizable Chinese communities grew up on Canyon City, John Day, and Baker through gold prospecting. They also lived around Jacksonville and Ashland for similar reasons. In Jacksonville, the Chinese did backbreaking work and had discriminatory taxes levied against them. An example of their oppression can be seen in the Oregon Sentinel of Jacksonville, on September 1, 1866:

“It seems an unwise policy to allow a race of brutish heathens who have nothing in common with is to exhaust our mineral lands without paying a heavy tax for their occupation. These people bring nothing with them to our shores, they add nothing to the permanent wealth of this country and so strong is their attachment to their own country they will not let their filthy carcasses lie in our soil. Could this people be taxed as to exclude them entirely it would be a blessing.”

The sections of towns where Chinese lived were highly restricted because of white laws and prejudices, but the Chinese also preferred to live in communal groups, and as a result Chinatowns developed in many towns in Oregon, and elsewhere around the United States. The elements of discrimination in this state serve as a foundation for the enduring contest for civil rights and inclusivity among the people of Oregon. There is a strong political and legal precedent among the will of the people of Oregon to insist upon their constitutionally protected rights as citizens in a democratic republic. The people’s will is a struggle for autonomy and self-determination that would continue into the Progressive Era at the turn of the twentieth century, when social and political reformers advocated for women’s suffrage, birth control, direct democracy, and the freedom of speech.

[1] Taylor, Quintard: “Slaves and Free Men: Blacks in the Oregon Country, 1840-1860

Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 2 (Summer, 1982), pp. 153-170

[2] Jeff LaLande: “Dixie” of the Pacific Northwest: Southern Oregon’s Civil War.”

Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 100, No. 1, (Spring, 1999), pp. 32-81.

[3] Section 6 of the 1844 exclusionary law by the Provisional Government of Oregon reads: “That if any such free Negro or mulatto shall fail to quit the country as required by this act, he or she may be arrested by some justice of the peace and if guilty upon trial before such justice, shall receive upon his or her bare back not less than twenty or more than thirty-nine stripes, to be inflicted by the constable of the proper county.”

[4] Peculiar Paradise, p. 30

[5] Ibid, p.35

[6] Ibid, p. 33

[7] Jepsen, David: Contested Boundaries: A New Pacific Northwest History, (John Wiley and Sons: 2017)

[8] Oregon Statesman, January 13, 1857

[9] Nokes, Gregory R.:, “The Exclusion Laws,” COLUMBIA: THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWEST HISTORYWINTER 2014–15 – VOL. 28 NO. 4

[10] Oregon Spectator Sept. 2, 1851

[11] Williams, George: Free State Letter, p. 254-273

[12] Ulysses S. Grant, who fought in the Mexican-American War, privately opposed the war in his memoirs in 1885. He labeled the Mexican War “the most unjust war ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation…an instance of a republic following the example of European monarchies.”

[13] Oregon Statesman, June 13, 1851

[14] McLagan, p. 46

[15] E. Kimbark MacColl: Merchants, Money and Power, (The Georgian Press: Athens, 1988)

[16] Malcolm Clark, Jr., Eden Seekers: The Settlement of Oregon, 1818-1862 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981) p. 289.

[17] Brooks, Cheryl, “Race, Politics, and Denial: Why Oregon Forgot to Ratify the Fourteenth Amendment,” 83 Oregon Law Review 731 (2004)

[18] George H. Williams: “The “Free-State Letter” of Judge George H. Williams.”

The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Sep., 1908), pp. 254- 273

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Oswald West Papers, Box 2 Mss 589, Oregon Historical Society.

[22] Journal of the Ninth Regular Session of the House of Representatives p. 51

[23] Oregon Statesman, March 17th, 1963.

[24] Knights of the Golden Circle, Original Documents, MSS 468, Oregon Historical Society Research Library.

[25] Morning Oregonian, February 8th, 1886.

[26] Charles Henry Carey, ed., The Oregon Constitution and Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of 1857 (Salem, Ore., 1926), p. 326.

[27] The pro-South Democratic Review newspaper from Eugene, Oregon bitterly opposed the rights of citizenship for African Americans, and channeled racist hysteria towards interracial marriage. Democrat Joseph Smith of Marion County during his election campaign for U.S. Congress asked voters: “Do you want your daughter to marry a nigger?” and “Would you allow a nigger to force himself into a seat at church between you and your wife?” Brooks, p. 744

[28] Blue Mountain Eagle, June 25th, 1981, p. 2.

[29] Annual Message of the Mayor; Portland City Directory, 1879.

[30] Daily Oregonian, April 10, 1867.

[31] The Oregonian, March 13, 1886.

[32] Nokes, Richard: Massacred for Gold, p. 77

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] In re IMPANELING AND INSTRUCTING THE GRAND JURY (1886), 11 Sawy. 522.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Clark, Malcolm (ed.): Pharisee Among Philistines: The Diary of Matthew Deady, (Oregon Historical Society Press: Portland, 1971) p. 62.

[38] Pennoyer Inaugural Address 1887 pp.20-25

[39] Oswald West Papers Box 1 MSS 589

[40] Vertical File: Oregon Population: Chinese Race Discrimination, Oregon Historical Society Archives.

[41] Grant County News, August 11, 1877.

[42] Grant County News, July 28, 1887.

[43] Grant County News, February 19, 1885.