8 Cold War and Counterculture

Victory for Civil Rights after World War II

The early 1950s marked a series of victories for the civil rights of African Americans and other marginalized people in Oregon. In 1949, a young black woman and her child were forced to sit in the segregated balcony at the Egyptian Theater on Portland’s Union Avenue. As a result of this incident a case was built to defeat segregation laws in public accommodations. Attorney Irvin Goodman drafted a statute to end Jim Crow segregation practices in Portland. He helped lead the fight to get it passed by Portland City Council. On February 22, 1950, by unanimous vote, Portland became the second city in the United States to ban racial discrimination in places of public accommodation. The state also prohibited discrimination in employment based on race, religion, color, or national origin, and a commission on intergroup relations was created. Although senators in the state capitol were hesitant, Oregon’s miscegenation law from 1866 was repealed in 1951, sixteen years before the U.S. Supreme Court declared interracial laws unconstitutional in the landmark decision Loving v. Virginia. A public accommodations law was established in 1953 that forbade discrimination in places of public accommodation like resorts or amusement parks, and established the right of all persons to equal facilities. It was the first major civil rights breakthrough since the 1920s. Some restaurants defied the tenor of the integrationist laws. They still held signs in their windows that read “White Trade Only-Please”; one such restaurant was Waddle’s, formerly located near the Interstate Bridge in Portland. Conservative groups, such as the Civil Freedom Committee, sought to oppose the repeal, but they failed to collect enough signatures to get a referendum on the law that was passed by the Oregon Senate.

Residential Segregation and Resistance in Oregon

The Portland Urban League sponsored a visit of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. to the city of Portland in 1961, and he spoke to an overflowing and receptive audience of more than 3,500 at the Portland Civic Auditorium. He encouraged his audience to fight for civil rights in Oregon by sharing the national progress being made by the Freedom Rides in Alabama and students protesting segregation at lunch counters in Mississippi: “If democracy is to live, segregation must die. Segregation is a cancer in the body of democracy that must be removed if the health of the nation is to survive.”

The Portland Urban League was founded in 1945 by a coalition of white and black Portlanders, including Dr. DeNorval Unthank, the Catholic and Episcopal Archdiocese, and the Jewish B’nai B’rith in response to the mounting housing crisis and fears of racial violence in Portland. Some of the coalition represented residents from the Eastmoreland, Council Crest and Grant Park neighborhoods. Dr. Unthank led a committee that investigated the practices and policies of the Portland Housing Authority, stating, “Present policies of tenant selection and placement have resulted in racially concentrated projects,” and that “racial concentrations were based on location.” The committee argued that the practices of the Housing Authority continued to produce intergroup tensions in Portland.

Edwin Berry, the executive director of the Portland Urban League, lobbied the legislature to adopt the Fair Employment Practices law. The legislature approved the measure, and Oregon became one of a handful of states in the nation to have a law banning employment discrimination. Berry and the Portland Urban League were instrumental in getting the Public Accommodations law passed through an active canvassing campaign. The Portland Urban League declared housing to be its greatest concern that year, and reported racist landlords left African Americans few options in the housing market. Realtors often directed black families to the Albina district, but some families moved in other areas in Portland and were met with resistance in all-white neighborhoods. A Word War II veteran moved his family into an all-white neighborhood and had a crossed burned on his front lawn. The Oregonian newspaper seized on this moment to educated the public on the topic of housing discrimination in their community, and helped bring awareness and get legislation passed. Segregation suddenly became a pressing political issue. As a result the Fair Housing Law was passed in 1957 which allowed blacks to move out of the Albina district to all white-neighborhoods in the suburbs of Portland.

Realtors, banks, and the Federal Housing Authority allowed for neighborhoods in America to practice de facto segregation and Oregon was no exception. In 1919, the Portland Realty Board had declared it unethical to sell property to a “Negro” or Chinese person in a white neighborhood. The realtors allegedly felt it was best to segregate people of color from whites in Portland so as to not cause depreciation in property values in white neighborhoods. The resettlement of Vanport flood victims reinforced patterns of segregation. Most African-Americans in Oregon lived in Portland, and the city’s continued neglect of public housing, combined with discrimination in realty and finance, created a disproportionate concentration of people of color in the Albina district. As more black people moved into the Williams Avenue area, the unofficial name of the city’s black district changed from Williams to Albina. By 1960, 80 percent of Portland’s 15,000 African American residents lived in the Albina District. The student population of the four elementary schools in the neighborhood, King, Humboldt, Boise and Eliot, were 90 percent black.[1]

De Facto Segregation of Schools

The Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 broke ground on the desegregation of schools in America. However, states like Arkansas actively resisted against integration of their public schools where a showdown between Governor Orval Faubus, Daisy Bates of the NAACP, and attorney Thurgood Marshall boiled over during the integration Little Rock Central High School. The story drew national attention when President Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army to escort nine African American students into the building. Whereas Oregonians did not have deeply entrenched segregationist policies in public schools. Josiah Failing, W.S. Ladd and E.D. Shattuck, board members of the Portland Public Schools, established a “Colored School.”[2] The segregated school remained open between 1867 and 1872 until thirty African American students were integrated into the Portland Public Schools. Since that time, de jure segregation has not existed in the public schools of Portland.

In response to Brown v. Board of Education, Portland Public Schools stated they provided equal education in their schools and the issue of segregation wasn’t a concern for the district. But de facto segregation of African American families existed in the city. By the 1960s, 80 percent of Portland’s African American population lived in the Albina district in Northeast Portland, and the African American community only accounted for 3 percent of the state’s population. The Oregonian noted the Eliot School in Lower Albina had 413 black children, and there are three whites, and one Chinese student in 1964.[3] At the Boise School, the student population was 85 percent African American. The issue of desegregation of schools in Portland remained to be a problem through the 1980s, and the Portland district failed to fully address the issue of segregation and its wider impact on the urban community.

Through the early 1960s, Oregon’s black community faced institutional discrimination, which meant black students continued to lag far behind the state’s average in education, occupational status, and income. African-Americans who sought to buy homes for their families faced discrimination despite passage of the Fair Housing Law. Another daunting problem for the African American community in Portland, like elsewhere in America, was the displacement families experienced under urban renewal projects. The construction of Memorial Coliseum (the former home of the Portland Trailblazers), Interstate 5, and Emmanuel Hospital destroyed many homes and businesses owned by members of the black community. The Eliot School, a racially concentrated school, was a victim of this form of “urban renewal”. The closest school to the Lloyd Center development was the Irvington School. When African American students arrived at Irvington, a few white families transferred their children to other schools in response.

Segregation was certainly felt in Oregon’s institutions of higher learning as well. In September 1943, Estella Mare Allen enrolled at the University of Oregon and was assigned to a single room as her domicile; she was told it was the only accommodation that was available for a black student. The following year, she was assigned a single room again, so she decided to live with three other female black students on campus. They were assigned an inferior dorm located next to the gymnasium, Gerlinger Hall. When the students complained that their living situation was inadequate and would prohibit their ability to study, the director of the dormitories told the students they would be moved into Susan Campbell Hall, but the white students and their parents objected.

Later in 1946, Barbara Kletzing, a white student, wished to live with Allen. The director of dormitories denied the students’ request stating the living arrangement allegedly was illegal according to state law, even though Allen lived with a white roommate the previous year on campus. A new college regulation stipulated that “neither Negro girls or boys will be permitted to room with white girls and boys, and Negroes will be kept to a minimum in the dormitories at the University of Oregon.” The University President stated in a letter to Allen, “We reserve the right to place students as we see fit in the dormitories. This policy and interpretation was the result of adverse public opinion concerning minority groups on the campus.” He further stated the situation was “too bad” and he was “very sorry [Allen] persisted in making a fuss over nothing.”[4] Kletzing, in a statement to the press during the heat of the controversy stated, “I, as a native white Oregonian, am not convinced however, that the people of Oregon have completely lost the love for individual freedom which they marched across the continent to establish.”

The president of the college, Harry Newburn held his position after inquiries by the NAACP and the Portland Urban League. In a letter to Edwin Berry he defended the college’s actions as legally justifiable: “As I stated to you last year, we believe this is entirely proper and that the long-range solution of the problem will be advanced through such leadership on the part of an institution such as ours. We reserve the right to put people together as we think best for the group and the State of Oregon.” Some white residents of Eugene, where the University of Oregon is located, defended the school’s position and used de facto segregation in the South as a reference point, where they claimed people never hear of complaints of discrimination. They argued that agitation for equal rights and fair treatment would only exacerbate the problem and make people become more prejudiced. This was the customary response among Oregonians who resisted civil rights reform and change throughout the state’s history: don’t upset the apple cart.

Cold War Tensions: Fear of Leftist Subversives in Oregon

The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union began with both nations reaching an impasse over the division of Europe and the competing spheres of influence between capitalism and communism around the globe. American diplomat George Kennan was instrumental in creating a world panic over the threat of a Soviet-led imperialism that could control all of Europe and Asia. Kennan stated the United States must meet this threat with an international obligation centered on containment of the Soviet Union.[5] On the home front, the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), an investigative committee of the House of Representatives, was created in 1938 to investigate disloyalty among citizens, politicians and organizations considered subversive who supported Fascist or Communist groups. In 1947, J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), gave a speech before members of the committee stating the FBI and HUAC are aligned towards the same goals and “quarantine is necessary to keep it [Communism] from infecting the nation.” Hoover targeted liberal policies as “window dressing” for Communist tactics, and the infiltration of communists into trade unions was a grand design of Lenin and Marx. Hoover called out the AFL and CIO to be on the alert for these threats, and the unions dutifully heeded the warning.

The CIO convention in Portland the following year became an orchestrated purge, and all unions suspected of having Communist ties were expelled from the organization. In 1949, the Oregon legislature barred all persons “linked to Communists” from state employment, and a “loyalty oath” was included in job applications. It was part of a larger national trend where employees across industries—teachers, physicians, journalists, scientists, tradespeople, and others—were mandated to sign loyalty oaths or affidavits, or face termination from their jobs. The Oregon legislature tried to purge those labelled “subversives” who held beliefs perceived hostile to the government by barring them from employment in Oregon. The thought was that without a stable job, they would be more likely to leave the state. Laws designed to protect Americans from communism were based on the legal precedent of the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1918, that a person’s beliefs could be considered a “clear and present danger” to national interests. When the Espionage and Seditions Acts were passed into law, the FBI began a lengthy tenure of intensive surveillance of American citizens that lasted until 1971. Under the guise of the “clear and present danger” principle initiated during the time of the Russian Revolution, internal threats could be associated with forms of political thought that were inimical to American power, and those expressing criticism could be labeled as criminals as seen in the Oregon Criminal Syndicalism law of 1930.

Entering the 1950s, Joseph McCarthy, the junior Senator from Wisconsin, became the face of HUAC. His name became associated with character assassination, libelous slander, and the destruction of peoples’ careers and reputations. He was known for his $64,000 question “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”, and if Americans refused to answer, they could be prosecuted and arrested for contempt of Congress. Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas associated McCarthyism with the “Black Silence of Fear” which was a landmark article in the New York Times assailing anxieties unleashed during the age of McCarthyism and its Great Inquisition. He warned Americans about arrogance, intolerance and militarism as grave threats to democracy and the free exchange of ideas. Douglas emphasized Stalinist communism prohibited the free marketplace of ideas and enforced state party orthodoxy. In America, fear guided lawmakers and citizens, and those who veered away from ideological orthodoxy were pilloried by the community. Douglas was an ardent supporter and defender of First Amendment rights. During his career on the bench at the United States Supreme Court, two attempts were made to impeach Douglas; one of those efforts was led by United States Representative Gerald Ford. Justice Douglas questioned the excesses of the containment of Communism in foreign policy and attempted to halt the bombing of Vietnam by U.S. war planes. Douglas also had a love for the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest and Oregon. He admired the groundbreaking work of scientist Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, an expose on the dangers of pesticides, and supported environmental causes in Oregon such as reducing pollution of the Willamette River and the preservation of Waldo Lake in Oregon.

HUAC hearings took place in Portland in 1954 to investigate and expose American citizens who were suspected of being communist subversives, or demonstrated opposition to any form of investigation of the “Communist conspiracy”. Four Portland residents, all World War II veterans, were arrested for failing to cooperate with HUAC. Linus Pauling, the Nobel-winning chemist who taught at Oregon State University, wrote a public statement condemning the persecution of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer. He had been suspended from the Atomic Energy Commission, by HUAC, because they claimed he posed a security risk. The Oregonian slammed Pauling for his “fuzzy thinking” on Dr. Oppenheimer, and felt those associated with communists were most likely corrupted by them.

Politicians opposed to civil rights often associated the movement with Communist sympathies and advocacy. Southern conservative congressmen preyed upon the idea that subversives were controlling the civil rights movement. They claimed alien elements with radical ideologies brought racial discord into Southern states that “Russia is directing the civil rights campaign to create a ‘great brown race’ in the South,” where communism and integration were considered “inseparable.”[6] J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI was also a proponent of the idea that civil rights and communist subversion were interconnected, and during the 1960s, the FBI engaged in efforts to monitor and disrupt the civil rights movement, especially the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and its leader Rev. Martin Luther King who the FBI viewed as “a likely target for Communist infiltration.”

The NAACP and the civil rights movement in Oregon continued its efforts to separate itself from Communists by declaring, “The Association will employ every reasonable measure in keeping with democratic organizational principles to prevent the endorsers, the supporters and defenders of a Communist conspiracy from joining or participating in any way in the work of the NAACP.”[7] The civil rights movement proceeded with caution due to Cold War tensions and conservative movements like the John Birch Society that opposed liberalism and social reform.

Julia Eaton Ruuttila participated in a City Hall demonstration for victims of the 1948 Vanport flood, many of whom remained homeless or had been assigned trailers by the Housing Authority of Portland. It became known to the protestors that the Housing Authority of Portland had been looking to close Vanport after the war, and board members wanted to eliminate it. Groups that supported the Vanport flood victims included the Oregon Wallace for President Committee, the Oregon CIO council, and the Oregon Communist Party along with the Oregon State Grange. The protest had interracial unity, and even achieved notoriety among celebrity activists. The actor and singer Paul Robeson, who later in his career was labelled a “communist subversive”, visited Portland to show his support for the refugees of Vanport. Several onlookers remarked at the demonstrators, “Why don’t they go back where they came from?”[8] Because of her association with the vanguard of the old left of Oregon, Ruuttila was attacked by members of the local media, such as S. Eugene Allen, editor of the Oregon Labor Press, who scathingly denounced her as “another energetic little lady who promotes the Communist Party line.” She was fired from her secretarial job at the Multnomah County Public Welfare Commission two weeks later for her involvement in other demonstrations associated with leftist groups. These activists were becoming increasingly targeted and alienated during the age of McCarthyism.

Julia Ruuttila was an advocate for social justice, known for her leftist beliefs and a devoted union-labor activist. She was subpoenaed to appear before the HUAC in Seattle in December of 1956 while she was living in Astoria. She was called before HUAC who questioned her writings in Communist newspapers that criticized actions of the American government. Congressman Gordon Scherer of Ohio asked Ruuttila if she opposed the Soviet actions in Hungary, and she stated she did. She was then asked if this caused her to want to break from the Communist Party. Richard Arens, the head attorney of HUAC, asked Ruutilla if she wanted to apologize for anything she has written. During the hearing, she was accused of being one of the “principal propagandists in the Northwest Communist conspiracy” because of her work to unionize lumber mills throughout the region. She invoked her fifth amendment rights and declined to state whether she was active in the Astoria and Clatsop County Committees for the Protection of the Foreign Born.[9] Work in this organization was directed at reforming the McCarran-Waters Immigration Act, which barred suspected Communists from entering the country.

Anti-Communism and the John Birch Society in Oregon

Oregon held conservative momentum to counterbalance liberal, progressive, and radical ideals entering the 1960s. The John Birch Society (JBS) claimed a few thousand members in the state of Oregon. Its founder, Robert Welch, spoke to audiences at Cleveland High School in Portland in 1966. The John Birch Society was a self-avowed anti-Communist group who stood opposed to leftist views, even considering the United Nations a “Communist instrument to control the world”. The group would pick up from where the Red Scare and antagonism of the House of Unamerican Activities Committee had left off in the previous decade.

Wallace Lee organized the John Birch Society in Oregon in 1959, and there were chapters in Grants Pass, Medford, Eugene, Newport, Lebanon, and Portland. The largest percentage of Birch members belonged to evangelical and fundamentalist Protestant Christian denominations. Early members included business executives and working professionals; by early 1961, the Oregon JBS had a dozen chapters, with four in Portland alone. In Eugene, the JBS fought against fluoridation of water, the United Nations, and radicalism at the University of Oregon which came to a head while Thomas McCall was governor. The Birch Society reached its peak nationally in the mid-1960s, but left a lasting impression in American political thought for decades.

Drawing from the legacy of McCarthyism, the JBS fueled the resurgent conservatism of the 1960s and was an ideological conduit for the New Right of the 1970s. President Richard Nixon led a grievance movement among American conservatives who he called the Silent Majority. They experienced a historical reckoning when the construction workers union assaulted student protestors on the streets of Manhattan and resisted against flags that were lowered in the wake of the Kent State University shootings on May 8th, 1970.[10] The Building and Construction Trades Council was led by Peter Brennan who was instrumental in fomenting the counter-protest and with support from the Nixon administration, union stewards were telling workers to join the fight.

John Birchers embraced the film Operation Abolition, which was produced by HUAC and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI, and held viewing parties for educational purposes. The film claimed “violent prone leftist radicals” under Communist influence wanted to destroy HUAC, to discredit the FBI’s “great director” J. Edgar Hoover, and “render sterile the security laws of our government.”[11] John Birchers opposed the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 advocated by Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. The John Birch Society became a living relic of the Cold War, with small chapters and a few American Opinion bookstores surviving past the year 2000 in places like Grants Pass, Hood River, and Portland.

The John Birchers built upon a historical, ideological trend that linked anti-radicalism with social conservatism. They seized upon an increasingly polarized American society caused by rifts due to Cold War political and social anxieties, and the conservative backlash against the civil rights movement. They proclaimed “no compromise and no coexistence” with those who were their sworn enemies. Anti-communism, disillusionment with the Eisenhower administration, and a concern about social issues brought John Birchers of Oregon together. Many felt President Eisenhower had allowed liberalism and Communist supporters to capture the Republican Party. Robert Welch labelled the president “a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy.”[12] Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, one of the primary architects of the second Red Scare agreed with that statement, and helped spread that rumor.

Urban Renewal and the African-American community in Portland

In the late 1960s, patience wore thin among the black community of Portland, and other American cities, with discrimination in housing and employment, destructive urban renewal projects, and police brutality. Portland experienced civil disorder during the “Long Hot Summer” of 1967 along with other cities around the United States, with race riots in the Albina District. In 1968, the Kerner Report on Civil Disorders set up by the Johnson administration in the wake of the race riots, declared the nation was moving toward two separate societies, white and black, and separate and unequal. The City Club of Portland the same year released the Report on Problems of Racial Justice in Portland. It documented evidence of racial discrimination and that “causative conditions persist to the present and demand action.” A section of the report titled “Police Policies, Attitudes and Practices,” stated that the Mayor of Portland and Chief of Police thought the findings of the Kerner Report didn’t apply to Portland, and went on to indicate that reform in the police department would be impossible until there was “a fundamental change in the philosophy of officials.”[13]

City planners and developers also contributed to the alienation of residents of the Albina District with destructive urban renewal projects, such as the Lloyd Center Mall and the Memorial Coliseum. African-Americans were increasingly frustrated by the demolition of hundreds of their homes and businesses to make way for events centers, highways, and public works projects, like Emmanuel Hospital. This created a diminution of faith in public officials. In all, the urban renewal projects of the Albina District wiped out the densest concentration of African-Americans and their community in Oregon. More than 600 homes were destroyed, along with the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was the second oldest church in Portland, and many black-owned shops and businesses. Dr. DeNorval Unthank’s medical offices were destroyed on two separate occasions by urban renewal projects.

The City Club report cited that in Portland, “substandard housing conditions exist most notably in the Albina district, but also in the southwest region of the city. There are mounting concerns over unsound and substandard buildings, fire conditions, sanitation issues and vermin, as well as litter.”[14] For the disenfranchised black community of Portland, rental homes and apartments were hard to find, real estate brokers were not color blind to potential renters, and lenders were reported as preferentially lending to whites over blacks of comparable financial standing. People of the black community were often told housing was not available, or that property had been taken off the market, or that another person had claimed a deposit and they would be called if the loan application did not go through. Blacks, in contrast to whites, were placed at a disadvantage in negotiating for purchase of property and subjected to a so-called “black tax,” which was not technically a tax, but did ensure that their offers could be refused if below the asking price, even though the majority of sales to whites was made below the asking price. Some real estate brokers harbored discriminatory attitudes and felt working with the African-American community would stigmatize their business interests. Some businessmen were hesitant to hire African-Americans even though most of their customers were black. Financial institutions were reluctant to offer business loans to African Americans as well. “[African Americans] cannot get a loan to start a business,” stated J. Allon Page, assistant chief investigator for the State Department of Justice, Welfare Recovery Division. “The financial institutions have offered woefully inadequate opportunities to experienced qualified blacks who want to go into business.”[15]

Radical Movement in the African American community

In the latter half of the 1960s, the black radical movement began to pick up momentum in various American cities, including Portland due to mounting frustration, disillusionment and resentment. The Portland Black Panther Party (BPP) was a part of the radical protest movement in Oregon during the 1960s and 1970s. Radical political groups in America like the Weathermen, an anarchist terrorist group, were bombing buildings and had aspirations to destroy the techno-capitalist system. The Black Panthers were not an anarchist terrorist organization. Their motivations were based on racial pride and preservation: African Americans’. first and second amendment rights (freedom of speech and right to bear arms), resisting police brutality, and providing social services such as free breakfast programs for children and healthcare. The party acquired its name from the work of Stokely Carmichael, a black leader, who became a prominent force in the civil rights movement in Alabama, a Jim Crow state, getting the vote out to disenfranchised blacks. The black panther symbolized the potency of the black franchise and a renewed activism in the African American community. Like many other radical protest groups, the BPP started in Portland because the black community had lost faith in public officials and held deep resentment towards the police. There was a lack of black representation in law enforcement, and white officers often used violence towards the African American community. There was a short lived Black Panther Party in Eugene as well.

African American radicals paid a price for their outspokenness, especially if they joined the Black Panther movement. The Portland Police after the Albina riot of 1967, bore down with increased surveillance on activists, their friends, and families in the Albina District. The Intelligence Unit of the Portland Police Department monitored all their movements where an Albina resident commented, “We feel like we are being watched all the time.”[17] At the federal level, the FBI declared war on activists when J. Edgar Hoover expanded the domestic counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO). The program primarily targeted leftist groups along with the Ku Klux Klan as hate groups. COINTELPRO sought to “expose and disrupt” black nationalist groups like the BPP as “hate-type organizations.” COINTELPRO designated resources to the local Portland FBI office and they coordinated efforts with the Portland Police to suppress the Panthers. Whereby spying on political organizations like the BPP was considered a legitimate police function and in a 1966 survey, police officials felt keeping track of subversives was the eighth most important responsibility of the police, above “traffic duties” and “helping little old ladies.”[18]

Originally the BPP started as a branch of the National Committee to Combat Fascism. The Portland BPP represented the black residents of the city who openly opposed city government and demanded complete control of the Albina District. Student protestors at Portland State University sided with their goals and were influenced by the activism and ideological underpinnings of the Portland BPP. The Portland Panthers chose to tackle such issues as poverty, use of extralegal force by police, inadequate health care services, general disfranchisement, and substandard educational opportunities. The Portland FBI office tried to persuade doctors to stop volunteering at the Black Panthers’ health and dental clinics.[19] People from the African-American community remember the Black Panther health, breakfast, and tutoring programs, while white residents and law enforcement officials saw the BPP as a threat to society that had to be removed. Kent Ford, a leader of the Portland Black Panthers, remembered “being hunted” and recalled long nights sitting “at the front door with a shotgun, waiting for a raid”. FBI agents and the Portland Police not only sat outside of Ford’s home, but approached and harassed their friends, families, and employers, as well as infiltrating Panther meetings.

Student Protests during the Vietnam War

A blossoming student protest movement representing a reconfiguration of the New Left swept across colleges and universities throughout the United States as the nation was pulled deeper into the Vietnam War quagmire. Some of the foundational elements that propelled the student movement were Tom Hayden, founder of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and author of the Port Huron Statement, Mario Savio, a key member of the Free Speech Movement at the University of California at Berkeley, and Ella Baker who mentored student activists like Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael and organized the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). All of these civil rights pioneers envisioned American colleges and universities as epicenters of empathetic cultural and cognitive change built on interpersonal relationships and a rejection of autocratic rule in societies and school administrations. Under their vision, institutions of higher learning served as crucibles of social reform and progenitors of authentic democratic values. Groups like the SDS and SNCC were making impactful strides in the civil rights movement through sit-ins at lunch counters and Freedom Rides. Students, professionals, clergy and others were devoted to non-violent protest and civil disobedience as catalysts for public awareness and engines of change. New York City, Portland, Oregon and Berkeley, California earned notoriety for their burgeoning counterculture movements. Columbia University, UC Berkeley and Portland State University were hornets’ nests of student protest and activity. According to the police, “Kids were flocking to Portland from everywhere in the country…where they could indulge in drugs like LSD and marijuana.”[20]

The University of Oregon was impacted by the international New Left movement that swept across college campuses. Dr. John R. Froines was a professor of chemistry at the university. He, along with Tom Hayden, were part of the Chicago Seven who were accused of conspiracy and inciting a riot. They were also charged with crossing state lines to conspire to commit violence in a series of protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Froines was acquitted of conspiracy at the infamous Chicago Seven trial in which Federal District Judge Julius Hoffman had Black Panther Party chairman Bobby Seale gagged and bound to a chair. Dr. Robert Clark, University of Oregon president, found no grounds to dismiss the professor from his academic duties. He stated, “Froines did not incite students to action prohibited by law or by the disciplinary code,” and that “conduct flagrantly unbecoming a faculty member” was not a sufficiently objective standard to be used in charges leading to dismissal.[21]

Clark defended Froines’s right of protest as a protected constitutional right scripted by our forefathers. He quoted Thomas Jefferson on the freedom of speech at the University of Virginia: “This institution will be based upon the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate error so long as reason is left free to combat it.” Oregon State representative Stafford Hansell, a Republican rancher from Hermiston, demanded that Froines be removed from the faculty. Hansell stated the support of student militancy and the Black Panthers had “given the state of Oregon a real black eye throughout the nation.”[22] Hansell, along with State Senator Lynn W. Newbry of Talent, Oregon, visited the campus of Oregon State University to tell faculty members that Oregonians were frustrated with their inability to instill discipline among the students. Disorders and violence had caused a deep-seated bitterness in the people of Oregon. Newbry told the faculty that he and Hansell were not there to tell them how to do their jobs, “We are here as legislators to help you people solve these problems.” He went on to say, “The general public does not understand higher education and the fact remains that they are deeply incensed by what is going on.”[23]

Governor Tom McCall released a press statement explaining that Dr. Froines, although he made a number of speeches advocating for the closure of a number of universities, had broken no laws and was able to remain at the university. Privately, McCall felt that Froines had “engaged in conduct contrary to the best interests of the system of higher education and inconsistent with his continuation as an employee. I feel a sense of frustration. I know what should be done, but there is no legal way this can be accomplished.”[24] The State Board of Higher Education was formulating a new code of conduct for faculty members and Governor McCall tried to leverage the changes, stating Froines was being put on notice, “he must conduct himself as a responsible member of the faculty, or else be subjected to immediate disciplinary action.” Froines said in response, “McCall is running for reelection this year. He obviously has made the decision that I’m a profitable campaign issue, and that political repression against me will result in his election.”[25] Eventually Dr. Froines was terminated from his tenure at the University of Oregon on June 30, 1971.

There were a series of student-led protests on college campuses between 1968 and 1970 at the University of Oregon, Portland State, Treasure Valley Community College, Reed College, and Oregon State University—where the ROTC building was firebombed. Governor McCall consistently distanced his political ideology from the far right and castigated Vice President Spiro Agnew’s incendiary attacks against student protestors by claiming, “Much of the spirit of unrest had been engendered by the Vice President’s unceasing attack on younger Americans…a steadily sarcastic running down our youth by a high official is hardly what this nation needs.”[26]

Blowback Against Student Protests

Not all students advocated or supported the actions of the ascendant New Left, and many felt their right to an education was being taken away or disrupted by the hyper-political atmosphere. Oregon conservatives pressured Governor McCall to consider a petition for a Teacher Investigation Law, which would have created grounds for termination of faculty whose conduct was “flagrantly unbecoming.” Business owners in Eugene wrote to McCall stating, “Students radicalized by faculty” were a threat to society, and they were “pill popping, LSD taking, influenced by the radical anarchistic speakers that the University seems to attract in the name of civil liberties or individual freedom.” Ultimately, many in Oregon felt “evil teachings should have no place in the educational system.” McCall received many petitions demanding the removal of faculty. The petition stated in its introductory heading,

“As a member of the Silent Majority a voter and taxpayer of the state of Oregon, I am angered and appalled at the state of anarchy that exists at our Universities and colleges. Any student participating in a demonstration that is prohibited by the rules of the member aiding or abetting in an organized protest, and any administrator who does not enforce the law should be terminated.”[27]

The blowback against the student protest movement was led by a conservative resurgence with the election of President Richard Nixon who addressed middle and working class Americans as part of a Silent Majority in 1969: “If a vocal minority, however fervent its cause, prevails over reason and the will of the majority, this Nation has no future as a free society.”[28] Nixon presented student protestors as an existential threat to the country. He repeated that message the following year when he announced the United States was expanding the war into Cambodia. “We live in an age of anarchy, both abroad and at home. We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilizations in the last 500 years. Even here in the United States, great universities are being systematically destroyed.”[29] The next day, four million students went on strike across American campuses, and on May 4th, the Ohio National Guard opened fire on protestors at Kent State University killing 4 students and injuring nine. Two weeks later, city and state police opened fire on students at Jackson State University killing two and wounding twelve, and about 400 bullets or pieces of buckshot were fired into the dormitory building, Alexander Hall at Jackson State.

Other Oregon politicians caught on to the furor to remove noncompliant faculty and instill law and order on college campuses. State representative Gerald Detering on May 15, 1970, the day of the Jackson State killings, pleaded for more law and order policies on Oregon college campuses:

“[The] Board of Higher Education [should] measure up to their obligation of providing law and order on the campuses of state supported institutions of higher learning, investigate with full authority to deal with and remove if necessary such faculty members who cooperate, aid or abet, and to participate in campus uprisings, most activities or other lawless actions that may or could require the presence of police or other law enforcement personnel.”[30]

Police Clash with Students at Portland State University

Historians have noted the class divide between law enforcement personnel and their families, and the student protestors who were active during the Vietnam War. The students of the New Left typically were middle-class whites who came from a more privileged background, compared to the working-class families of police officers. This class division was felt when police violently engaged student protestors on the campuses of Columbia University and Portland State University.

Previous to the police attacks on the student protestors, a number of Portland State University students met on May 4th, 1970, to discuss a student strike in response to the United States’ involvement in Cambodia. A group of students began to formulate plans for the strike with the idea of focusing attention on the President’s action in Cambodia and to “help make the classroom activities more relevant to the troubles of the world.”[31] Students focused their strike on four issues: the bombing of Cambodia, the shipping of nerve gas into Umatilla, Oregon (Governor McCall also opposed it), the death of the students at Kent State, and the trial of Black Panther Bobby Seale. The weekend after the Kent State shooting, a coalition of Portland State and local activists staged rallies and marches into downtown Portland. The colleges of Lewis and Clark, Marylhurst, and Portland Community College remained open during this time. The student strike swept through the campus in downtown Portland, and thoroughfares and roads were barricaded by the students. The Park Blocks barricades became “communities of brotherhood,” and symbolized the spirit of the student strike and resistance. The barricades were given different names, like Fort Tricia Nixon, Freedom Suite, Katanga Junction, and Bobby Seal Memorial, which changed its name after a garbage truck smashed through it; it was renamed Wipe Out Alley.[32]

On May 11, 1970, the Portland Police Tactical Operations division descended onto the South Park Blocks, clearing the area of makeshift barricades. Nearly 170 police officers attacked strikers and supporters as the students linked arms around a hospital tent. The students were attacked by a marching wedge of police officers armed with riot sticks. The officers clubbed and punched anyone in the park not wearing a police uniform. No one was spared; officers even bludgeoned a student on crutches. The action sent thirty-one people to the hospital. Tom Geil, a student taking photographs for the Vanguard, Portland State’s student paper, captured on film baton-swinging police officers assaulting student protestors on campus. “I just felt this anger…I never thought they would actually go in and start hitting people.” Similar to the Kent State and Jackson State shootings, the violence at Portland State lasted less than two minutes.

Dr. Gregory Wolfe, the president of Portland State indicated, “The university did not call the police. In fact we were attempting to persuade City Hall to postpone their actions when the order to move was given to the Police Tactical Squad.”[33] It was later revealed that Portland Mayor Terry Schrunk played a major role in the police suppression of protestors. Political pressure had been mounting from citizenry, state officials, and Portland State students, who were outraged by the peaceful demonstrations at PSU. Mayor Schrunk was getting calls from “substantial businessmen who offered to get their shotguns and chase those people out.”[34] Frustrated students and citizens demanded that campus be reopened and the barricades be taken down, and the mayor agreed. The original settlement between the university administration, and the mayor’s office was that the barricades would be taken down with a “symbolic” number of police in attendance, twelve or so, not 170.[35]

After investigations were conducted regarding the police melee at Portland State, several conclusions were made. There was no evidence students were rioting when the police riot squad engaged with the students. All evidence indicated there was relative quiet on both the campus and the Park Blocks prior to the arrival of the riot squad. The police were supposed to be there to assist Portland Parks Bureau with the removal of the barricades, but it was the decision of Mayor Schrunk and the chief of police to remove the hospital tent, inciting the violent encounter. In the final report by the Police Relations Committee, they found the students were not rioting; they were merely dissenting:

“We have found that the police erred in the method used to remove the tent. The [riot] squad resorted to violence in a non-violent situation. In other words, there were other alternatives at the disposal of the police other than the use of force. The most obvious would be to place those who resisted under arrest. We have been unable to find any justification for the use of force by the police as their first step in removing the tent. Neither the law nor standard police procedures can be used to condone unprovoked and unnecessary use of force by police officers.”[36]

Resentment brewed among Portland State students, and a small group discussed retribution for the police beating in the Park Blocks. President Wolfe told Mayor Schrunk, “The circumstances did probably more to create a sense of bitter reaction among students who had been hitherto uninvolved, than anything else that could have happened.” Robert Low, vice president of the college, denounced the incident as “unnecessary violence.”[37]

After the clash with police in the Park Blocks on May 11, there was another protest parade the following day. By the end of the week, 3,000 marchers assembled around City Hall, but Schrunk refused to meet with the protestors. He stated in a press conference, “I am very proud of the actions of the Bureau of the police, the calm they have displayed in the face of obscenities…I am sorry that any blood was spilled, but I also want to point out to the press and the people of Portland there was some phony activities up there. There was some red dye used in some areas.” A local newsman from the KGW TV station asked the mayor, “You spoke of phony activities on the part of the demonstrators. When a police officer knocks down a girl and straddles her and beats her with a club again and again while she is down, is that a phony activity on the part of the police office?” The mayor quickly responded, “I didn’t see it and it’s certainly hard to believe,” to which the reporter interrupted, “We have film.”[38]

In the aftermath of the Portland State melee, A. Lee Henderson, the minister of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopalian Church, empathized with the students who were victimized by police brutality as something he is very familiar with:

“In our own city the local police mishandled the ‘Albina disturbance’ in June 1969 and also at Portland State. There was a slight difference this time at Portland State it was against white people. We are praying that this city, nation, and world would come to realize that black lives are as precious as white lives.”[39]

Vortex I Concert and War Protest

McCall worried about the divisiveness of the era and its potential explosiveness. “We are in danger of becoming a society that could commit suicide.”[40] Privately he supported the Cambodian invasion, but he also stated his outrage to Vice President Spiro Agnew: “The nation will not stand for our straying into a new bottomless quagmire in Southeast Asia.” Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and was one of only two senators who voted against the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1964, which gave President Johnson and the executive branch unfettered authority and decision making power during the war. Morse stated that, “President Nixon has conducted the war with dishonor. He talks about peace with honor. Let us face up to the fact that we have a President who has waged war with dishonor to the everlasting bloodstain of this republic.”[41]

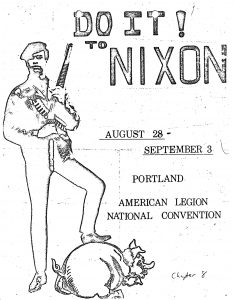

McCall was sickened by the police violence at Portland State. In June 1970, FBI agents arrived at the governor’s office for a meeting with McCall. They informed the governor they had received word from the Portland FBI that 50,000 young people calling themselves the People’s Army Jamboree were planning to descend onto Portland to protest a visit from President Nixon. The president was giving the keynote address at the national convention of the American Legion in Portland. The Legion was the largest veteran’s group in the nation, and they anticipated 25,000 Legionnaires showing up to the convention. Officials feared the two sides would have erupted into a massive violent riot. According to the Portland FBI, this would have made the Democratic National Convention in Chicago “look like a tea party.”[42] Declassified FBI records showed that local agents’ alarm over a possible clash of the titans between the two polarized groups was greatly exaggerated; the People’s Army Jamboree was a much smaller group than what the Portland FBI had suggested. Most of the intelligence of the Portland branch of the FBI was gathered from the Oregon Journal, the Portland State student newspaper the Vanguard, and informants on the PSU campus. Students protesters could not have organized a People’s Army Jamboree of that size, and yet the leaders of the group enjoyed the press they received and exploited it. People’s Army Jamboree literature whipped up animosity among members of the New Left. “The American Legion claims to stand for 100% Americanism and to [us] this means standing for the worst in America…In New Orleans in 1968 at the American Legion Convention, drunken legionnaires went on a rampage in the hip community, busting up head shops and beating up longhairs.”[43]

Two prominent members of the People’s Army Jamboree, Robert Wehe and Glen Swift, visited the governor’s office to propose their plan to state official Ed Westerdahl. The People’s Army wanted an alternative to a possible clash with the American Legion, and the proposal was a rock concert, like Woodstock, to be set up near Portland. The festival was called “Vortex I, A Biodegradable Festival of Life;” and was held at McIver State Park in Clackamas County, thirty miles southeast of Portland in the town of Estacada. A flyer for the concert event read, “The first bio-degradable festival of life laying the groundwork for a totally free, harmonious and ecological celebration of life. Not American life, not human life, but all life.”[44]

The festival seemed to solve a potentially major problem. The plan for Vortex was that the state promoted and managed the operations of the concert. When the plan was presented to McCall, his initial reaction was, “Westerdahl, are you crazy? Are you out of your goddamn mind?” After he calmed down and thought about it, McCall committed himself to the political gamble of supporting the festival, even with an upcoming reelection bid on the line.[45] Residents of the logging town of Estacada fumed over the plans for Vortex. The governor received angry phone calls from citizens, including a woman who thought the best way to solve the problem of the protestors was to shoot them.[46] Letters came pouring in to the governor’s office from around the state. One from Estacada said, “It is unbelievable that the highest office in our fair state is sanctifying a drug party—Vortex I. The prospect of letting even one hippie contaminate [McIver State Park] it makes us ill, let alone a band of thousands of them for days.” Residents and the press called it a “bread and circus provision” comparable to the days of the Roman Empire.

City officials in Portland were apprehensive about the Portland FBI office stating “a working figure of thirty thousand in the People’s Army Jamboree is not at all unreasonable,” which contrasted from J. Edgar Hoover’s analysis which did not consider the situation as dire or a massive security threat. Nevertheless, McCall was not going to gamble during an election year. There was a push to provide other means than simply a state-sponsored rock festival to prevent violence and chaos. State and city government felt the city should not avoid developing additional plans for facilities and defusing potential violence. The National Guard were put on call and were conducting exercises in Portland which heightened alarm and anxiety throughout the city. The containment of the Vortex situation was officially known as Operation Tranquility to the Oregon National Guard.[47] The American Legion president, J. Miller Patrick, exacerbated the situation and increased people’s anxieties by declaring that the National Guard should be armed and prepared to fire. “Until we treat [protestors] as common criminals, we will never solve the ills of this country,” he said.

McCall was able to take advantage of the impending encounter between the People’s Army and the American Legion. He gave a widely televised speech defending the First Amendment rights of the protestors, and an unrelenting stance toward putting down violence and the forces of anarchy. He defended the Vortex plan as a necessary security measure for the sake of public safety. About 3,000 Oregon Guardsmen were deployed in downtown Portland under orders from the governor “to use minimum force required to accomplish their objective. I stated long ago that I did not intend to see another Kent State episode in Oregon.”[48]

During the course of the week-long rock festival, which ran from August 28 through September 3, police officers assisted concertgoers to the site, and people were allowed to have free reign over certain non-violent offenses like public nudity and drug use. Another music festival called Sky River took place in Washougal, Washington, about thirty miles east of Portland. Estimates were that approximately 50,000 concert goers attended each event. At one point, a group of the People’s Army came close to a clash with Portland City Police, but an elderly woman intercepted the police and waved her finger at them stating, “Go back, you police just make trouble. Why, you even incense me.”[49]

In the end, McCall’s gamble paid off. Vortex I was a success and remains the only state-sponsored rock festival, and McCall easily won reelection. Letters came into the governor’s office supporting his decision for the Vortex plan, and they far outweighed the letters in opposition. Opinions varied throughout the state indicating less political polarization between urban and rural Oregonians; whereas today, the political divide between urban and rural sectors is more glaring and rigid. Some of the praiseworthy letters complimented the governor, “Stroke of genius…let’s have another Vortex festival next year.” Whereas opponents stated, “You are letting the degenerates dictate to you…We have the same policy (appeasement with Hitler) with the scum of the earth known as hippies.” McCall responded to letters with the default refrain that in the end of the potential crisis, there was “a single broken window, and no broken heads.”

During the protest movements that were unleashed during the Vietnam War, Portland and Eugene became epicenters of countercultural activity with coffeehouses, rock concerts, communal living, and other forms of the blossoming counterculture. Ken Kesey, an author who lived in Oregon after attending Stanford University in California, helped inaugurate the counterculture movement and its psychedelic culture through his enduring relationship with the rock band The Grateful Dead. Kesey wrote such classic works of the latter twentieth century as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion. Both novels were transformed into Hollywood films that were shot in Oregon. These cinematic events further put Oregon on the map of the counterculture movement and brought an alternative option to migrants from other parts of the nation seeking solace in a “hippie” environment.

Milos Forman, the director of the movie One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, upon the invitation of the Superintendent of the State Hospital of Oregon Dr. Dean Brooks, was allowed to shoot the film on the campus of the Oregon State Hospital while patients resided there. Forman lived at the Oregon State Hospital for six weeks, along with the actors. Dr. Brooks allowed Forman to study the cases of several patients. Jack Nicholson, one of the actors in the film, witnessed electroshock therapy being administered to a patient at the hospital, and stated the experience completely transformed him. Many film viewers gravitated to the dilapidated condition of the buildings, which were assumed to be props, not actual dwellings for people who lived at the Oregon State Hospital. Dean Brooks argued that the film was not controversial but instead “exploded into consciousness the things we have refused to look at.” Michael Douglas, the producer of the film, stated that Cuckoo’s Nest “was an allegory about life in an authoritarian structure. It was not an attack on mental institutions.” Yet, Oregon ranked in the bottom half of the fifty states in terms of the quality of its mental health services. Regardless of Douglas’s allegory, the film put a dark cloud upon the historical memory of Oregon’s mental health services and institutions. The end of the twentieth century marked a requiem for the Fairview Training Center in Salem, and an exposure of malpractice and violation of patients’ rights at the Oregon State Hospital.

At the end of the twentieth century, Oregon emerged as a state built on progressive values toward human diversity and inclusion. Like other parts of America, the formative years of the counterculture and the Civil Rights Era began to mark indelible political divisions between rural and urban America, and Oregon was no exception. Cultural wars pitted environmentalists against the logging and mining industries, and marginalized groups came under attack such as Hispanics and the gay community in the coming decades.

[1] Serbulo, Leanne and Gibson, Karen: “Black and Blue: Police-Community Relations in Portland’s Albina District, 1964–1985,” Oregon Historical Quarterly , Vol. 114, No. 1 (Spring 2013), pp. 6-37

[2] Johnson, Ethan and Williams, Felicia: “Desegregation and Multiculturalism in the Portland Public Schools,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, (Volume 111, no.1, Spring 2010)

[3] The Oregonian, September 15th, 1959.

[4] Stella Maris House Collection, University of Oregon folder, OHS: MSS 1585, Box 3.

[5] Later in his career he stated that containment policy was not the correct approach.

[6] Brown, Sarah Hart: Congressional Anti-Communism and the Segregationist South: From New Orleans to Atlanta, 1954-1958,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 80, No. 4 (WINTER 1996), pp. 785-816

[7] Resolution NAACP Convention, June 26th 1956.

[8] McElderry, Stuart: “Vanport Conspiracy Rumors and Social Relations in Portland, 1940-1950,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 99, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 134-163.

[9] Julia Ruutila Papers MSS 250 Box 2, Oregon Historical Society Archives

[10] Many college students in America did not support students who protested the war in Vietnam, and were frustrated by the disruptions they created on college campuses. For some, the Kent State shooting were not seen as a tragedy, and they blamed the students for the shootings.

[11] Film: Operation Abolition (1960)

[12] Toy, Eckard: “The Right Side of the 1960s: The Origins of the John Birch Society in the Pacific Northwest,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 105, No. 2 (Summer, 2004), pp. 260-283.

[13] Serbulo, Leanne and Gibson, Karen: p. 6.

[14] Report on Problems of Racial Justice in Portland from Portland City Club Bulletin June 14, 1968, p. 32 in Stella Maris House Collection Box 3 Mss 1585, Oregon Historical Society Archives

[15] The Oregonian, August 18th, 1967.

[16] Eldridge Cleaver, one of the leaders of the BPP, brought negative attention to the group which helped paint a poor picture of the group as potentially racist and misogynist. Cleaver described rape of women as an insurrectionary act, and therefore appropriate.

[17] Serbulo, Leanne and Gibson, Karen: p. 13.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid. p. 14

[20] Ibid, p. 89.

[21] University of Oregon Office of the President, Clark statement re: results of Froines hearing.

[22] President Geoffrey Wolfe Records BOX 14, Student Protest Folder, Portland State University Archives

[23] Ibid.

[24] Tom McCall Papers Collection, Mss 625, Box 11, Oregon Historical Society Archives.

[25] New Republic, September 12, 1970.

[26] Tom McCall Papers, MSS 625 Box 10, Oregon Historical Society.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Presidential Address, November 3rd, 1969.

[29] Presidential Address, April 30th, 1970.

[30] Tom McCall Papers.

[31] Vanguard Newspaper, Portland State University, May 5th 1970.

[32] Vanguard, Portland State University, May 8th, 1970.

[33] President Gregory Wolfe Records BOX 14 Portland State University Archives

[34] The Oregonian, May 7th, 2010.

[35] Report of the Police Relations Committee of the Portland Metropolitan Human Relations Commission: Gregory Wolfe Papers, PSU Archives.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Vanguard Newspaper, May 12th, 1970.

[38]Vanguard Newspaper, May 15th, 1970

[39] Tom McCall Papers. Vietnam and Protest folder.

[40] Fire at Eden’s Gate, p. 284.

[41] Vietnam War: Vertical File Folder, OHS

[42] Fire at Eden’s Gate, p. 287.

[43] Peoples’ Army Jamboree Pamphlet, President Geoffrey Wolfe Records, Box 14, Portland State University Archives

[44] Tom McCall Papers, Oregon Historical Society, MSS 625 Box 11.

[45] Fire at Eden’s Gate, p. 290

[46] Ibid. p. 294

[47] Tom McCall Papers Collection Mss 625 Box 11.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Walth, Brent, Fire at Eden’s Gate: Tom McCall and the Oregon Story, (Oregon Historical Society Press: Portland, 1994) p. 300.