3.4 Social Science Research Methods

In this section we take a closer look at a variety of research methods that are commonly used in social science research. Here you will learn more about surveys, experiments, ethnography, interviews, content analysis, and community-based action research.

3.4.1 Surveys

Do you strongly agree? Agree? Neither agree or disagree? Disagree? Strongly disagree? You’ve probably completed your fair share of surveys, if you’ve heard this before. At some point, most people in the United States respond to some type of survey. The 2020 U.S. Census is an excellent example of a large-scale survey intended to gather sociological data. Since 1790, the United States has conducted a survey consisting of six questions to receive demographic data of the residents who live in the United States.

As a research method, a survey collects data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods. The standard survey format allows individuals a level of anonymity in which they can express personal ideas.

Not all surveys are considered sociological research. Many surveys people commonly encounter focus on identifying marketing needs and strategies rather than testing a hypothesis or contributing to social science knowledge. Questions such as, “How many hot dogs do you eat in a month?” or “Were the staff helpful?” are not usually designed as scientific research. Surveys gather different types of information from people. While surveys are not great at capturing the ways people really behave in social situations, they are a great method for discovering how people feel, think, and act—or at least how they say they feel, think, and act. Surveys can track preferences for presidential candidates or reported individual behaviors (such as sleeping, driving, or texting habits) or information such as employment status, income, and education levels.

A survey targets a specific population, people who are the focus of a study, such as college athletes, international students, or teenagers living with type 1 (juvenile-onset) diabetes. Most researchers choose to survey a small sector of the population, or a sample, a manageable number of subjects who represent a larger population. The success of a study depends on how well a population is represented by the sample. In a random sample, every person in a population has the same chance of being chosen for the study. As a result, a Gallup Poll, if conducted with nationwide random sampling, should be able to provide an accurate estimate of public opinion if it only contacts 2,000 people.

When writing survey questions, you should avoid confusing phrasing and offer a range of response categories. It’s good practice to use thoughtful wording that will minimize the risk of bias in responses. You can do this by presenting both sides of attitude scales which will help you avoid social desirability bias (Schutt 2017). Part of designing questionnaires requires researchers to build on existing survey instruments, which is why you conduct exhaustive literature reviews related to your topic. Refining and even testing your questions offers you an opportunity to gain feedback on the design. Often a question makes sense in our minds, but reading it aloud or having another read it can help identify problems with proposed questions. Interpretive questions permit the researcher to learn more about what participants’ responses mean. Thoughtful ordering of questions and maintaining a consistent focus helps the research participant or respondent understand what the survey is about.

A common survey instrument is a questionnaire. Surveys can be carried out online, over the phone, by mail, or face-to-face. Research participants often answer a series of closed-ended questions. The researcher might ask yes-or-no or multiple-choice questions, allowing subjects to choose possible responses to each question. This kind of questionnaire collects quantitative data—data in numerical form that can be counted and statistically analyzed. You could just count up the number of “yes” and “no” responses or correct answers, and chart them into percentages. Another common type of questionnaire is based on the Likert scale. Likert scale formatting allows participants to respond along a continuum; for example, they can select an option from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Questionnaires can also ask more complex questions with more complex answers—beyond “yes,” “no,” or checkbox options. These types of inquiries use open-ended questions that require short essay responses. Participants willing to take the time to write those answers might convey personal religious beliefs, political views, goals, or morals. The answers are subjective and vary from person to person. For example, an open-ended question might be, How do you plan to use your college education?

After your questionnaire is ready, it is important to inform participants of the nature and purpose of the survey up front. We will talk more about the importance of informed consent and research ethics later in this chapter in the “Ethics” section.

Survey data can be quantified and researchers can analyze responses using statistics. Numbers that are presented in the media are routinely assumed to be correct when we should think a bit more about the sample used in data collection and strategies for evaluating statistics. For example, if you were to hear that 90% of college students still use facebook as their main source of social media you would likely be pretty surprised. However, if you learned that the sample was 10 college students, perhaps who are all in the same facebook group, the findings might seem a bit less surprising and maybe not entirely representative of all college students. In this case, it is important to examine the response rate of your survey. Response rate refers to the percentage of surveys completed by respondents and returned to the researchers. For a survey to be valid, there must be an adequate response rate. Once surveys are returned researchers can begin analyzing the data.

Sociologist Joel Best offers some suggestions to help us identify common mistakes when examining statistical data. In popular media, there are a few statistical blunders that lead to misconceptions about data (Best 2008). Slippery decimal points refer to when the decimal point is misplaced (to the right or left). When this happens look for numbers that are surprisingly large or small. Another blunder is botched translations. This is when people repeat a statistic that they do not actually understand. If they try to explain the numbers they get it wrong. Look for explanations that translate statistics into simple language. Misleading graphs occur when people get the numbers wrong. Be aware of graphs that are hard to decipher and that do not fit the actual data. Finally, careless calculations can lead to reporting on the final numbers and leaving the whole calculation process hidden. Again you can look for numbers that seem surprisingly low or high as a way to help identify this blunder.

Researchers aim to understand the relationship between variables. Researchers look for ways to identify relationships like causation and correlation. Causation refers to a change in one variable that directly has an effect on or causes another variable (I hiked 10 miles, now my feet are tired). Correlation is a broad term describing how a change in one variable is associated with a similar pattern of variation in another variable across cases in a data set. Correlations imply a relationship between two or more variables but do not suggest causation. For more examples explaining causation and correction, check out the 5 minute video in the next section, “Pedagogical Element: A Closer look at Causation and Correlation.”

3.4.2 Activity: A Closer Look at Causation and Correlation

Distinguishing between these concepts is a valuable skill. For example, does ice cream kill? Or is something else going on? Learn more about causation and correlation by watching How Ice Cream Kills! Correlation vs. Causation [YouTube Video].

Figure 3.4. Screenshot from How Ice Cream Kills! Correlation vs. Causation [YouTube Video]

Be sure to come back and answer these questions:

- What are some examples of correlations that do not indicate causation?

- How does the ability to distinguish between these concepts help us when we are analyzing data?

3.4.3 Experiments

One way researchers test social theories is by conducting an experiment, meaning they investigate relationships to test a hypothesis. An experiment refers to a procedure typically used to confirm the validity of a hypothesis by comparing the outcomes of one or more experimental groups to a control group on a given measure. This approach closely resembles the scientific method. Researchers select this approach when they want to focus on isolating variables. In order to do this, they create a controlled setting, a setting where the researcher has complete control of factors associated with the study. Not all questions about social interaction and social life can be answered with this approach, but it helps us learn more about patterns in controlled environments.

There are two main types of experiments: lab-based experiments and natural or field experiments. In a lab setting, the research can be controlled so that data can be recorded in a limited amount of time. In a natural or field-based experiment, the time it takes to gather the data cannot be controlled but the information might be considered more accurate since it was collected without interference or intervention by the researcher. Field-based experiments are often used to evaluate interventions in educational settings and health (Baldassarri and Abascal 2017).

As a research method, either type of sociological experiment is useful for testing if-then statements: if a particular thing happens (cause), then another particular thing will result (effect). To set up a lab-based experiment, sociologists create artificial situations that allow them to manipulate variables.

Typically, the sociologist selects a set of people with similar characteristics, such as age, class, race, or education. Those people are divided into two groups. One is the experimental group and the other is the control group. The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable(s) and the control group is not. To test the benefits of tutoring, for example, the sociologist might provide tutoring to the experimental group of students but not to the control group. Then both groups would be tested for differences in performance to see if tutoring had an effect on the experimental group of students. As you can imagine, in a case like this, the researcher would not want to jeopardize the accomplishments of either group of students, so the setting would be somewhat artificial. The test would not be for a grade reflected on their permanent record as a student, for example.

And if a researcher told the students they would be observed as part of a study on measuring the effectiveness of tutoring, the students might not behave naturally. This is called the Hawthorne effect—which occurs when people change their behavior because they know they are being watched as part of a study. The Hawthorne effect is unavoidable in some research studies because sociologists have to make the purpose of the study known. Subjects must be aware that they are being observed, and a certain amount of artificiality may result (Sonnenfeld 1985).

Although this approach closely resembles the scientific method, there are some limitations researchers need to consider. Experiments work best when research can be conducted in a controlled setting, but controlled settings may not accurately reflect the complexities of the real world. Another limitation to consider is that experimental research with human subjects often uses some level of deception to gather information. To avoid influencing the results of the experiment, participants may not be told of the true purpose of the study. It is important to follow ethical guidelines and have a post-participation debriefing where researchers can fully explain the experiment and offer them support as they work through the effects of deception.

3.4.4 Ethnography (Field Research)

Another research method sociologists used to collect data is ethnography—studying people in their own environments in order to understand the meanings they give to their activities. The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet people where they live, work, and play. Ethnography or ethnographic research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment. This field research or “field work” requires the sociologist to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds.

In field work, the sociologists, rather than the people under study, are the ones out of their element. The researcher interacts with or observes people and gathers data along the way. While field research often begins in a specific setting, the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviors in that setting. Ethnographers aim to provide a “thick description” of the setting and interactions they observe (Geertz 1973). For example, rather than writing “Parker smiled,” the researcher would elaborate on what is observable and may write something like “They parted their lips with an upward lift at the ends of their mouth, displaying a few top teeth”—the approach of “thick description” aims for the researcher to both account for what they see and the context they view it in as a way to deeply understand society. This level of detail can make the reader feel as though they are experiencing the setting first hand. Ethnographic research is conducted through participant observation. Generally, the goal is to study groups of people and understand what is meaningful to group members, but there are other types of ethnography that we will learn about in the next sections. Some center the experience of the researcher (autoethnography) and other approaches analyze gendered relations in power structures (institutional ethnography).

3.4.4.1 Participant Observation

Participant observation refers to a style of ethnographic research where researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. For instance, a researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, experience homelessness for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside. The ethnographer will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, and the researcher will be able either make connections to existing theories or develop new theories based on their observations. This approach will guide the researcher in analyzing data and generating results.

Researchers use participant observation as an ethnographic tool to help them gain insight into cultural practices and phenomena. Once researchers gain access to their fieldsite, they need to consider what their role as a participant observer will be. Adler and Adler (1987) outline different types of roles researchers take in their fieldsites. As a peripheral member, researchers would have daily or near-daily interactions with members that vary from acquaintanceship to close friendship with key informants. This role is not as embedded in the context as active members. This role facilitates trust and acceptance of the researcher, but increases the identification of the researcher with members of the setting. To maintain this role, the researcher must undergo self-reflexivity and periodic withdrawal from the setting. Finally, complete members are immersed in their research setting. In this role, the researcher may study a setting or group that they already have membership in.

How do researchers decide what roles to maintain in their fieldsite? Several factors influence roles in the setting. Conditions of settings may limit or enable the researcher’s level of participation. Personal characteristics of the researcher, including abilities, theoretical orientations, demographic characteristics and others may influence the researcher’s membership in the setting. Finally, a researcher’s role may change over time due to changes in either the researcher or the setting during data collection (Adler and Adler 1987).

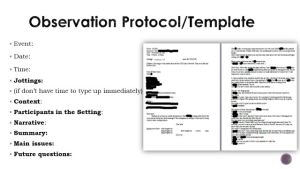

Researchers gain insights to cultural practices over time and through repeated analysis of many aspects of fieldsites. To facilitate this process, ethnographers must learn how to take useful and reliable notes regarding the details of life in their research contexts. These fieldnotes will constitute a major part of the data researchers will analyze and connect to sociological theories. As you can see in figure 3.5, fieldnotes are often taken with brief handwritten “jottings” while a researcher is observing participants in the field. Jottings refer to the keywords or phrases researchers will write down to help them remember what occurred when they are elaborating on their notes later. Some researchers will use their phones or other recording devices to capture pictures, interactions, or even record their impressions of a setting. Later those brief notes will be typed and expanded on. Figure 3.6 shows an example of an observation protocol or template that the authors of your text find helpful in their own research. Consistently documenting your observations helps with data Many researchers use qualitative data management software to help them organize the documents they analyze which later conclusions will be based.

3.4.4.2 Autoethnography

Autoethnography is a form of participant observation where the researchers use self-reflection and writing to examine their experiences in a setting. They connect their autobiographical story to wider cultural, political, and social meanings and understandings (Ellis 2004; Marechal 2010). Autoethnographic methods include journaling, interviewing one’s own self, and generating cultural understanding through reflective writing.

3.4.4.3 Institutional Ethnography

Institutional ethnography is an extension of basic ethnographic research principles that focuses on gendered relationships within institutions. Developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy E. Smith (1990), institutional ethnography is often considered a feminist-inspired approach to social analysis and primarily considers women’s experiences within male- dominated societies and power structures. Smith’s work is seen to challenge sociology’s exclusion of women, both academically and in the study of women’s lives (Fenstermaker, n.d.).

Historically, social science research tended to objectify women and ignore their experiences except as viewed from the male perspective. Modern feminists note that describing women, and other marginalized groups, as subordinates helps those in authority maintain their own dominant positions (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada n.d.). Smith’s three major works explored what she called “the conceptual practices of power” and are still considered seminal works in feminist theory and ethnography (Fensternmaker n.d.).

3.4.4.4 International Research

International research is conducted outside of the researcher’s own immediate geography and society. This work carries additional challenges considering that researchers often work in regions and cultures different from their own. Researchers need to make special considerations in order to counter their own biases, navigate linguistic challenges and ensure the best cross cultural understanding possible. Look at this map and descriptions of field projects around the world by students at Oxford University’s Masters in Development Studies. What are some interesting projects that stand out to you?

For example, in 2021 Jörg Friedrichs at Oxford published his research on Muslim hate crimes in areas of North England where Islam is the majority religion. He studied police data of racial and religious hate crimes in two districts to look for patterns related to the crimes. He related those patterns to the wider context of community relations between Muslims and other groups, and presented his research to practitioners in police, local government and civil society (Friedrichs 2021).

3.4.5 Activity: A Closer Look at Indigenous Knowledge and Decolonizing Research Methods

An emerging fieldwork methodology involves the production of Indigenous knowledge by Indigenous communities themselves. Indigenous communities are distinct social and cultural groups that share collective ancestral ties to the lands and natural resources where they live, occupy or from which they have been displaced. As the world becomes increasingly aware of the environmental crisis, researchers are more often acknowledging the ways that indigenous peoples care for their ecological surroundings. For example, communities and fire agencies in Northern California and the Northwest are looking to Indigenous fire management practices to help control wildfires (Kuhn 2021). As Indigenous communities conduct their own fieldwork to identify and document their own knowledge they are able to engage with research as agents of ecological conservation.

Alongside better recognition of Indigenous knowledges is a recent emphasis on research methods insights led by Indigenous leaders and scholars. This body of methods emerges as a response to the colonialist roots of international fieldwork and the damage that has been caused by some researcher-community relationships. The roots of international fieldwork are tied to the regime of settler colonialism and colonialist thinking that came with it. Until recently international fieldwork was viewed as the study of the “exotic” other.

Many argue that contemporary international fieldwork needs to be decolonized (Kim 2019, Datta 2018). Decolonization refers to the active resistance against colonial powers. It involves a shifting of power towards political, economic, educational, cultural, psychic independence that originates from a colonized nation’s own indigenous culture. This context prompts the urgency to bring in diverse voices and perspectives, along with an expectation that researchers’ engage in some level of reflexivity in their studies. In other words, researchers should acknowledge their own reactions and motives in the field.

An early promoter of these ideas is Linda Tuhiwai Smith (of the Māori iwi (tribes) Ngati Awa and Ngati Porou) in New Zealand. In her 1999 book, Decolonizing Methodologies Tuhiwai Smith encourages scholars to “research back,” or critically and creatively interrogate the role that one’s self, discipline, and community has played in engaging with communities of study in a way that can shift our knowledge in the present. Researching back disrupts colonizing practices, attempting to move toward respectful, ethical, and useful practices (Tuhiwai Smith 1999).We can explore this concept more in Decolonizing Methodologies: Can relational research be a basis for renewed relationships? [YouTube Video].

Please watch the 5 minute video (figure 3.7) where Dr. Shawn Wilson and Dr. Monica Mulrennan at Concordia University in Monréal, Québec, Canada explore decolonized methodologies in research.

While watching, consider these main ideas: Research should be community defined with the process itself collaborative; research should look for and be guided by community strengths; and outcomes should be meaningful, promoting improvements to the community, at times serving a reconciliation process.

Figure 3.7. Decolonizing Methodologies: Can relational research be a basis for renewed relationships? [YouTube Video]

Considering the ideas in the video, take a moment to reflect on these questions:

- The film mentioned that indigenous research methods can provide an opportunity for the renewal of relationships between those working within systems of research and indigenous communities? How do you see this renewal can happen?

- What does the quote by the indigenous geographer, mentioned in the film, mean to you? “…if we assume we’re guests we will be welcome, but if we assume we’ll be welcome we’re no longer guests.

3.4.6 Qualitative Interviews

Interviews, sometimes referred to as in-depth interviews, are one on one conversations with participants designed to gather information about a particular topic. When you have a research topic, there are several questions to consider to determine if interviewing is the best method to conduct your study:

- Are you looking for nuance and subtlety?

- Does answering the research question require you to trace how present situations resulted from prior events?

- Is an entirely fresh view required? If the existing literature cannot explain your research problem or the current approaches to the topic do not seem to be headed anywhere, interviews allow you to look at the topic (possibly) in a different way. Interviews can provide new perspectives on the issue.

- Are you trying to explain the unexpected?

If you answered yes to these questions, qualitative interviewing would most likely be an appropriate method (Weiss 1994).

Interviews can take a long time to complete, but they can produce very rich data. In fact, in an interview, a respondent might say something that the researcher had not previously considered, which can help focus the research project. Researchers have to be careful not to use leading questions. You want to avoid leading the respondent into certain kinds of answers by asking questions like, “You really like eating vegetables, don’t you?” Instead researchers should allow the respondent to answer freely by asking questions like, “How do you feel about eating vegetables?” A strength of this approach occurs during the back-and-forth conversation of an interview where a researcher can ask for clarification, spend more time on a subtopic, or ask additional questions.

3.4.6.1 Developing an Interview Guide or Protocol

When designing an interview study, it is important to think about how different types of questions can engage the participant. Most questions should be open ended because it allows the answer to take whatever form the respondent chooses. The respondent can give lots of information, examples, and personal experiences, all of which could provide valuable data to the researcher. Closed-ended questions may be more likely to resemble survey type responses.

The goal when structuring interview guides or protocols is to ask questions that will provide depth and detail about the situation or topic. Detail allows you to understand the unexpected or learn about things that may initially seem unimportant. Depth means getting the distinct points of views while getting enough context to put the different pieces of what you heard together in a meaningful way. It is looking for answers beyond the superficial level. In seeking depth, knowledge, and detail, you explore alternative perspectives. Interviewers use probes which are techniques to keep the interviewee discussing the topic to learn more. By asking interviewees to elaborate or following up with comments like “mmhmm” or “then what?” researchers are able to get more detail without changing the focus of what is being said.

When structuring an interview guide, you should start out broadly and then narrow the questions as you learn more. Main questions will provide the framework for your interview. They help the interviewee talk about the main puzzles and topics you are interested in. They help make sure your research problem is explored thoroughly. These questions translate your research topic into language that is understandable and relatable to the interviewees. You will also use follow up questions which are specific questions in response to the comments made by the interviewees. It involves listening carefully to what they are saying and then asking additional questions to explore the topics, themes, and ideas brought up by the interviewee (Rubin and Rubin 2005). Give your interviewees the opportunity to answer as they see fit and avoid yes or no questions as they limit dialogue between the researcher and the interviewee.

3.4.6.2 Finding Interviewees and Conducting Interviews

After you’ve designed your interview guide, it’s time to recruit people to participate in your study. Ideally the people you interview should be experienced and knowledgeable in the area you are interviewing. Finding people with first hand relevant experience will help make your findings convincing. You also want your interviewees to be knowledgeable, the caveat here is that people you might expect to have knowledge on the topic will not necessarily be the most well informed. Rarely will you find an individual who has answers to all the information you seek. The credibility of interview findings can be enhanced by making sure you get a variety of perspectives on the topic. You can try to gather contradictory or overlapping perceptions and select interviewees that you think will give you a different perspective on the topic.

People are usually more than willing to talk to you if they know who you are. You can get to know people by immersing yourself in the research setting (perhaps as an ethnographic component). Another option is to use your social networks. You could start with people you know in the group and then ask them to provide names of other people that may be interested in participating in the study, an approach called snowball sampling.

Once you have recruited people to your study, you want to build trust with your interviewees. There are several things you can do to build trust, such as sharing aspects of your background that you have in common with the interviewee. Getting someone to vouch for you can also be useful in building trust. Further, being seen as honest, open, fair, and accepting helps build trust. Before going into the interview you want to make sure the interviewees know what the study is about. Explain that participation is voluntary, and their participation will be helpful.

There are a few limitations to consider before selecting this approach. There is a risk that some respondents may not be truthful or forthcoming on the interview subject. The topic may be difficult to discuss or the respondent may be concerned about being presented favorably. A skilled interviewer will be able to encourage meaningful responses. Similar to ethnographic research, the sample used by the researcher may not be representative of the population. Interviews are time consuming so are rarely conducted with large numbers of people. Instead interviews can provide us with depth and detail.

3.4.7 Secondary Data Analysis

While sociologists often engage in original research studies, they also contribute knowledge to the discipline through secondary data analysis. Secondary data does not result from firsthand research collected from primary sources. Instead secondary data uses data collected by other researchers or data collected by an agency or organization. Sociologists might study works written by historians, economists, teachers, or early sociologists. They might search through periodicals, newspapers, or magazines, or organizational data from any period in history.

3.4.7.1 Content Analysis

Content analysis is the systematic analysis of forms of communication to identify and study patterns and themes. Using available information not only saves time and money but can also add depth to a study. Sociologists often interpret findings in a new way, a way that was not part of an author’s original purpose or intention. To study how women were encouraged to act and behave in the 1960s, for example, a researcher might watch movies, television shows, and situation comedies from that period. Or to research changes in behavior and attitudes due to the emergence of television in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a sociologist would rely on new interpretations of secondary data. Decades from now, researchers will most likely conduct similar studies on the advent of mobile phones, the Internet, or social media.

Social scientists also learn by analyzing the research of a variety of agencies. Governmental departments and global groups, like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics or the World Health Organization (WHO), publish studies with findings that are useful to sociologists. A public statistic like the foreclosure rate might be useful for studying the effects of a recession. A racial demographic profile might be compared with data on education funding to examine the resources accessible by different groups.

3.4.7.2 Advantages and Limitations of Secondary Data

One of the advantages of secondary data like old movies or WHO statistics is that it is nonreactive research (or unobtrusive research), meaning that it does not involve direct contact with subjects and will not alter or influence people’s behaviors. Unlike studies requiring direct contact with people, using previously published data does not require entering a population and the investment and risks inherent in that research process.

Using available data does have its challenges. Public records are not always easy to access. A researcher will need to do some legwork to track them down and gain access to records. To guide the search through a vast library of materials and avoid wasting time reading unrelated sources, sociologists employ content analysis, applying a systematic approach to record and value information gleaned from secondary data as they relate to the study at hand.

Another problem arises when data are unavailable in the exact form needed or do not survey the topic from the precise angle the researcher seeks. For example, the average salaries paid to professors at a public school is public record. But these figures do not necessarily reveal how long it took each professor to reach the salary range, what their educational backgrounds are, or how long they’ve been teaching.

When conducting content analysis, it is important to consider the date of publication of an existing source and to take into account attitudes and common cultural ideals that may have influenced the research. For example, when Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd gathered research in the 1920s on a small town in the Midwest, attitudes and cultural norms were vastly different then than they are now. Beliefs about gender roles, race, education, and work have changed significantly since then. At the time, the study’s purpose was to reveal insights about small U.S. communities. Today, it is an illustration of 1920s attitudes and values.

3.4.8 Community-Based Research and Participatory Action Research

Community-based research takes place in community settings and involves community members in the design. This style of research also engages community members in the implementation of research projects. Research projects involve collaboration between researchers and community partners, whether the community partners are formally structured community-based organizations or informal groups of individual community members.The aim of this type of research is to benefit the community by achieving social justice through social action and change.

Community-based research is sometimes called participatory action research (Stringer 2007). In partnership with community organizations, you utilize your social science research skills to help assess needs, outcomes, and provide data that can be used to improve living conditions. The research is rigorous and often published in professional reports and presented to the board of directors for the organization you are working with. As it sounds, “action research” suggests that we make a plan to implement changes. Often with academic research, we aim to learn more about a population and leave the next steps up to others. This is an important part of the puzzle, as we need to start with knowledge but action research often has the goal of “fixing” something or at least quickly translating the newly acquired findings into a solution for a social problem.

3.4.9 Activity: A Closer Look at Participatory Research

To learn more about participatory action research, check out this short 4-minute clip for an introduction with Shirah Haasan of Just Practice in Participatory Action Research [YouTube Video]

Figure 3.8. Participatory Action Research [YouTube Video]

Be sure to come back after watching to answer these questions:

- What is participatory action research?

- What are the benefits of this type of research? Who holds the “power” in this type of research?

- When do we see the effects of participatory action research?

- What are some ways that elements of this type of research are transferable to other settings? What examples does Shirah Haasan give?

Community-based action research rigorous research, developed from empirical findings. At times this research uses an interpretive framework (this reflective approach is discussed in “Approaches to Sociological Research). It engages people who have traditionally been referred to as “subjects” as active participants in the research process. The researcher is working with the organization during the whole process and will likely bring in different project design elements based on the needs of the organization. As a social scientist, you may bring your more formalized training, but you have to draw both on existing research/literature and goals of the organization you are working with. Community-based research or participatory research can be thought of as an orientation for research rather than strictly a method. Often a number of different methods are used to collect data. Change can often be one of the main aims of the project (ie how to improve access to housing). Think of this as a practical outcome related to the lives or work of research participants (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988; Anderson, Herr, and Nihlen 1994; and Reason 1994).

Community-based research projects can benefit the community in a variety of ways, but there are a few considerations researchers and organizations should consider before entering into a partnership. For example, funding and time may be issues. With limited financial resources, it may be difficult to complete projects in a timely manner or at all. For projects that include collaborations between universities (faculty and students) with community organizations, the groups may have different timelines and goals. Projects may take longer to complete than one quarter or semester which means there may be turn over in the research team. Researchers also need to consider the readiness of communities to undertake research that may challenge current practices.

In the next sections, we will look at some examples of how ethnographic fieldwork has been used in community-based research and social action efforts both locally and internationally. A quick examination of your local community in Oregon demonstrates how social science research methods are applied in the region. Consider how the case shared in the next section, “Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Research in the Community” reveals the consequences of interlocking systems of oppression.

3.4.10 Activity: A Closer Look at Research in the Community

Research is not always equitable, but it impacts our society, our local communities, and us as individuals in a multitude of ways. Let’s examine one instance.

Lisa Saldana, a clinical psychologist, uses social research methods to address the needs of children who are referred to Oregon Department of Human Service (ODHS) or child protective services. A disproportionate number of these children come from families with substance use disorder or a drug-related referral, such as neglect (Saldana 2016). Psychology and sociology tend to have different points of analysis with sociologists focusing on societal issues and patterns, while psychologists focus on the brain and the mind. Saldana used a sociological approach to her research, focusing on the micro-experience of the individual within the meso- and macro-system (family and ODHS, respectively) in order to address societal issues that increased referrals to child protective services.

Saldana’s (2021) qualitative research resulted in Families Actively Improving Relationships (FAIR), a community-based program that provides services to people where they live and work. FAIR’s treatment program focuses on mental health, parenting, substance use disorder, and ancillary needs. Clinicians meet the clients wherever they can, whether that’s McDonalds, the park, their home, or homeless shelters. This integral part of the program seeks to address the barriers often found within these communities, such as poverty, lack of access and transportation, and unemployment.

One of the barriers Saldana was surprised by was the insistence by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) that only women were allowed to participate in the trial. On the surface this seems to challenge the exclusion of women in social research. When we examine this through Dorothy Smith’s (1990) theoretical framework, we realize that this gender restriction continues to objectify women and excludes men as fathers and their experiences within the system.

Following the successful trial, Saldana and her team received requests from the community to continue this work and as a result of the research, opened a funded clinic in a Medicaid billable environment in Lane County, allowing FAIR to be utilized by more individuals, including men. The rate of success for men was approximately the same as that of the women, allowing families to grow and remain together which benefits not only the children and the parents, but society as a whole.

While this new clinic allowed more individuals to be reached and engaged, it was only for those who had the complications of co-occurring mental health and substance use problems, along with looking for or needing parent skills training. Saldana, her team, and community members realized that there were more individuals who needed support and assistance but were ineligible for existing services as they were not currently misusing opioids nor methamphetamine.

Employing semi-structured interviews with graduated FAIR parents and current or former FAIR clinicians, the FAIR program was adapted to create a prevention-oriented intervention (PRE-FAIR). PRE-FAIR is currently in its efficacy trial in Benton, Douglas, Linn, and Lane counties. These efficacy trials would not be in place today without the use of social science research methods. We rely on social science research to help us identify the needs of people in our communities.

Saldana’s work showcases the unique and often unexpected ways research impacts or fails to impact various populations and identities due to ingrained biases, objectification, and oppression. To learn more about the FAIR program, you can visit https://www.oslc.org/projects/fair/. Additional resources can be located here: https://www.odiclinic.org/

3.4.11 Licenses and Attributions for Social Science Research Methods

“Survey” – last 2 sentences of first paragraph, paragraphs 2-4, and 6-7 are from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods, edited for consistency and brevity.

Correlation definition from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Causation and Correlation” and figure 3.4 screenshot image and video is adapted from How Ice Cream Kills! Correlation vs. Causation by DecisionSkills. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Experiment” first sentence of first paragraph, first 3 sentences of second paragraph and paragraphs 3-5 are edited for consistency and brevity from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods

Experiment definition from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Ethnography”

First 3 sentences of paragraph 2 from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods

“Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Ethnography” and figure 3.4 screenshot image and video is adapted from Ethnography: Ellen Isaacs at TEDxBroadway by TEDx Talks. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

“Participant Observation” the last 4 sentences of paragraph 1 and paragraph 2 are from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods

Images

Figure 3.5. Photo by Kari Shea. License: Unsplash

Figure 3.6. Photo by Jennifer Puentes licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Institutional Ethnography” edited for clarity and brevity from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods

“International Research” is original content by Aimee Krouskop and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Indigenous Knowledge and Decolonizing Research Methods” and figure 3.7 screenshot and video adapted from Decolonizing Methodologies: Can relational research be a basis for renewed relationships? (c) Concordia University. License Terms: Standard YouTube License. All other content in this section is original content by Aimee Krouskop, Matthew Gougherty, and Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Decolonization definition from Racial Equity Tools Used Under Fair Use. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resources/fundamentals/core-concepts/decolonization-theory-and-practice

Indigenous communities definition from indigenous peoples definition from World Bank Used Under Fair Use https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples

“Qualitative Interviews” is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Secondary Data Analysis” edited for clarity and brevity from “2.2 Research Methods” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods

Content analysis definition from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Community-Based Research and Participatory Action Research” is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Community-based research definition adapted from San Francisco State University Used Under Fair Use.

“Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Participatory Research” and figure 3.8 screenshot adapted from Participatory Action Research. (c) Vera Institute of Justice. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

“Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Research in the Community” is original content by Sonya James and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.