9.5 Movements for Change: Feminism

In this chapter you learned about many different types of gender inequality. You might be wondering what has been done to address these issues. The feminist movement (also known as the women’s liberation movement, the women’s movement, or simply feminism) refers to a series of political campaigns for reform on a variety of issues that affect women’s quality of life. Although there have been feminist movements all over the world, this section will focus on the four eras of the feminist movement in the United States. We first introduced feminist theory in Chapter 2 we focused on the third wave. Now you will learn how each type of feminist theory has slightly different goals, often highlighting the needs of an underrepresented group at a given historical moment. Feminism argues that women and men should have equal legal and political rights. The movement advocates for economic, political, and social equality regardless of the sex one is assigned at birth. This theoretical perspective argues that the systematic oppression of people based on gender is problematic and should be changed. In the United States, we identify each of the main campaigns in women’s history as “waves.” Current social movements suggest we are in the fourth wave.

9.5.1 First Wave: Suffrage Movement (1800s–1920s)

The first wave aimed to obtain voting rights for women and educational access. The movement began with a convention in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848 organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott (History.com 2022). With about 300 women and men participants at the convention, a Declaration of Sentiments was signed stating that men and women were created equal and women should be granted the right to vote. American women eventually won the right to vote in 1920. Women’s suffragists collected signatures to support their right to vote and marched in parades to increase the visibility of their cause (figure 9.16).

The movement had significant links to the abolitionist and suffragette forums with activists such as Sojourner Truth and Paulie Murray. The first wave understood equal rights as the admission of women to political and economic spaces. However, legally achieving the right to vote and having access to education did not mean feminism had achieved the goal of equality.

9.5.2 Second Wave: The Problem That Had No Name (1960s–1980s)

The second wave was fueled by activism centered on gaining equal access to education and employment for women (figure 9.17). Culturally and politically, we saw the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963, the establishment of National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, and the development of women’s consciousness raising groups. Friedan’s (1963) writings uncovered the “problem with no name” that was impacting women everywhere. This “problem” was the widespread unhappiness of women in the 1950s and 1960s. She argued that the dissatisfaction women expressed about their lives indicated that women no longer found traditional gender roles fulfilling.

The decades of the 1960s and 70s unfolded within a framework of anti-war movements, distrust of the state, the civil rights movement, and growing awareness about social minorities beyond gender or race. Radical thinking within the movement already existed from the first wave. It became normalized and adopted as a fundamental part of feminist behavior. Voices like those of Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis, and Dolores Huerta became representative of the movement. Themes centered on reproductive and sexual rights, feminine empowerment, anticolonialism, and the stirrings of intersectionalities.

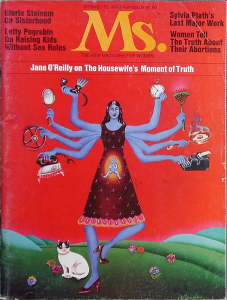

The involvement of more women outside the home transformed feminism. It was no longer just about women as a single group. Popular magazines served as useful tools to spread information about the feminst movement (figure 9.18). Feminism began to encompass diverse topics such as women and civil rights, women and work, women and rural labor, among others. By the 1990s, feminism consolidated as a social movement with a global reach. These years marked the end of the second wave and the beginning of the third. A different conceptual framework emerged to change how we understand grassroots feminism and its diversification, including queer theory.

9.5.3 Third Wave: Centering Diverse Voices (1990s–2008)

The third wave emerged out of the feminist criticisms that the first two waves primarily focused on the needs of women who were mostly white and middle class. This reaction came at a time when feminism was influenced by postmoderism. Previous feminist movements often marginalized and overlooked the concerns of women of color, lesbians, and working class invididuals. One of the goals we see in the third wave is to work towards social justice and equity along the lines of race, social class, sex, gender, and sexuality. By centering the experiences of women of color, the third wave is also concerned with globalization and women’s rights in all countries.

As you learned in the activity “Pedagogical element: Intersectionality,” Crenshaw discusses intersectionality as the idea that we experience life, including opportunities and discrimination based on a number of different identities that we have. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality became important to understanding how multiple identities are intertwined and impact life chances for individuals and groups.

In addition to intersectionality, we see the emergence of queer theory during the third wave. You will learn more about queer theory in Chapter 10. The decade of the 1980s was especially hard for the LGBTQIA+ community. The public response to the AIDS epidemic made clear the need to create organizations that advocated for the human dignity of non-heteronormative people. Gender and sexuality became the subject of both feminism and the LGBTQIA+ movement. Queer theory encompasses three actions: 1) promoting sexual expressions other than heterosexuality, 2) challenging the belief that lesbian and gay sexuality studies are one, and 3) shining the light on how race influences sexual biases.

Third wave feminists effectively used mass media, particularly the web (“cybergrrls” and “netgrrls”), to create a feminism that is global, multicultural, and boundary-crossing. One important third wave sub-group was the Riot Grrrl movement (figure 9.19), whose DIY (do it yourself) ethos produced a number of influential, independent feminist musicians, such as Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney. Third wave feminism’s focus on identity and the blurring of boundaries, however, did not effectively address many persistent macrosociological issues such as sexual harassment and sexual assault, which will become a focus of fourth-wave feminists.

9.5.4 Fourth Wave: #MeToo #TimesUp (2008–present)

The fourth and current wave of feminism maintains a focus on intersectionality and empowering women by removing the stigma associated with experiences with sexual harassment, body shaming, and rape culture. Social media and the internet play a large role in building awareness around social injustices, particularly through internet activism. The fourth wave critically examines gender norms and the marginalization of women while seeking gender equity.

During this wave, social media has offered women an opportunity to speak up and share their experiences about sexual harrassment, sexual violence, and sexism in the workplace. Within a matter of seconds, the internet provided a tool for women to speak freely about topics in their own words. In the next section, “Pedagogical Element: Origins of the Me Too Movement,” you’ll have an opportunity to learn more about how this movement started and evolved with the use of social media.

Accusations against men in powerful positions—from Hollywood directors, to Supreme Court justices, to the President of the United States, have catalyzed feminists in a way that appears to be fundamentally different compared to previous movements. We can already see some of the impact of this movement on some laws. Some states are banning nondisclosure agreements that cover sexual harassment and expanding protections for workers that are not covered by federal sexual harrasment and state laws, such as independent contractors (North 2019).

Historian Martha Rampton captures the spirit of fourth wave feminists well. Rampton (2015) states, “The emerging fourth wavers are not just reincarnations of their second wave grandmothers; they bring to the discussion important perspectives taught by third wave feminism; they speak in terms of intersectionality whereby women’s suppression can only fully be understood in a context of the marginalization of other groups and genders—feminism is part of a larger consciousness of oppression along with racism, ageism, classism, ableism, and sexual orientation (no “ism” to go with that).”

Will the next generation of activists help us move into the 5th wave of feminism? How might this movement intertwine with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade in June 2022? How will leaders of a new movement continue to draw on the work of their predecessors? As we raise these questions, we are excited to see how feminist movements will continue to evolve.

9.5.5 Activity: Origins of the Me Too Movement

In this short video, you will learn more about #metoo and how it connects to a movement started in 2006.

Figure 9.20. Founder of “Me Too” movement speaks out [YouTube Video]

Please watch the Founder of “Me Too” movement speaks out [YouTube Video] and come back to answer the following questions:

- In what ways does the “Me Too” movement connect experiences across racial categories?

- How has technology played a role shaping activism?

To learn more about women’s opinions on the #MeToo movement, check out Women are not as divided on #MeToo as it may seem [YouTube Video].

9.5.6 Licenses and Attributions for Movements for Change: Feminism

“Movements for Change: Feminism” is from “Feminist Movements and Feminist Theory” in Lumen/Openstax Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/lumensociology2/chapter/the-womens-movement/

Third sentence of first paragraph used, paragraph 9 (third wave), first sentence of paragraph 12 and 13 (fourth wave) edited for consistency and clarity; all other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Movements for Change: Feminism” is from “Why Isn’t Feminism Just One Movement?” by Sofía García-Bullé in Observatory of Educational Innovation of Tecnológico de Monterrey, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://observatory.tec.mx/edu-news/four-waves-feminism. Paragraphs 3 (first wave), 5-6 (second wave), and 9 (third wave) edited for consistency and clarity, all other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Feminism definition expanded from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.16. Photo by Unknown author – The New York Times photo archive. Used under fair use.

Figure 9.17. Photo by Hollis for Archival Discovery. Used under fair use.

Figure 9.18. Photo by Liberty Media for Women, LLC from Ms. magazine cover, Spring 1972 issue. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.19. Photo by RockCreek. License: CC BY 2.0.

“Pedagogical Element: Origins of the Me Too Movement” and Figure 9.20 screenshot adapted from Founder of “Me Too” movement speaks out by CBS News. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.