7.4 Race, Identity, and the Criminal Justice System

A criminal justice system is an organization that exists to enforce a legal code. There are three branches of the U.S. criminal justice system: the police, the courts, and the corrections system.

Police are a civil force in charge of enforcing laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level. No unified national police force exists in the United States, although there are federal law enforcement officers. Once a crime has been committed and a violator has been identified by the police, the case goes to court. A court is a system that has the authority to make decisions based on law. The U.S. judicial system is divided into federal courts and state courts. The corrections system is charged with supervising individuals who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offense, plus people detained while awaiting hearings, trials, or other procedures.

While the criminal justice system, like other institutions in the United States, is supposed to treat all people equally, there are significant inequalities in how this system treats different groups. Criminal justice inequalities are a serious social problem because of the life-altering impact of the criminal justice system on a person’s life. For instance, once an individual has been convicted of a felony, they can no longer access public benefits, such as food stamps or public housing. In addition, they often struggle to find employment and can be legally denied housing. In some states, they are denied the right to vote.

Racial inequality is incredibly prevalent throughout the criminal justice system. Black and Latino Americans are overrepresented at every stage of the legal process (from policing to parole and probation) and regularly face harsher consequences than white Americans for similar offenses.

These inequalities did not arise by accident. Instead, scholars have outlined how the War on Drugs and other “tough on crime policies” are simply the latest iteration of racialized institutional practices designed to control, disenfranchise, and marginalize black and Latino Americans by further perpetuating racial inequality.

Racial disparities are not the only concerning trends and inequalities in this system. More recently, women’s incarceration rates have also been increasing, despite broader trends to reduce prison populations. There is also considerable evidence that individuals marginalized by their sexuality or gender identity are disproportionately funneled into the criminal justice system and lack basic civil rights protections if incarcerated.

Finally, there are significant issues with how the system addresses mental health issues. The criminal justice system disproportionately impacts people with mental health issues. They are more likely to be killed by police officers than those without mental health issues and are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated. Many jails and prisons incarcerate individuals who require mental health services that are absent or inadequate within these facilities. As we’ve mentioned, it is important to take an intersectional approach to understand how people’s experiences vary. It is not just one aspect of an individual’s identity that determines their experience with the criminal justice system. Instead, we need to look at how these group memberships (race, sexuality, gender identity, or ability) interact and influence individuals’ treatment and patterns of inequality.

7.4.1 Policing and Race

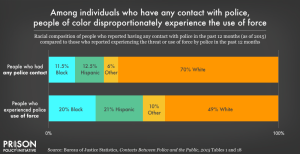

People of color, particularly black and Latino Americans, are disproportionately surveilled and killed by the police. Between 1980 and 2018, police killed an estimated 30,800 people. Black and Latino Americans were significantly more likely to be killed than white Americans (Sharara et al. 2021). Public opinion studies from the Pew Research center show that black Americans are more likely to report having been stopped unfairly by police. They are also less likely to have a positive view of how officers treat different racial and ethnic groups and see fatal police shootings as signs of broader issues with the criminal justice system (Desilver, Lipka, and Fahmy 2020). Black Americans have very different interactions with police than white Americans, which appear in their differences in opinion about the police.

So, what are the explanations for the disproportionate impact? There are a few factors that contribute to these trends. The first explanation for racial disparities in policing is the role of spatial profiling. High-crime, low-income neighborhoods are more heavily surveilled by the police compared to low-crime, middle and upper-class neighborhoods. It is in these neighborhoods that black and Latino Americans are more likely to live, exposing them to more significant contact with the police.

Police training may also play a significant role. For example,topics such as ethics, de-escalation tactics, and providing social services only have a few hours dedicated to them in training. Instead, using firearms, defensive tactics, and police procedures comprise most of the training. Consequently, it is not surprising that police are more adept at using their weapons when a situation escalates rather than turning to nonviolent options.

The next explanation is bias—both explicit and implicit. Explicit bias is still an issue with at least some proportion of law enforcement officers. A recent study analyzing 40 years of General Social Survey data has shown that police, unlike Americans, believe that they should receive more funding and have the right to use physical force against citizens (Roscigno and Preito-Hodge 2021). They also found that white male officers were, in particular, more racist than the general population or those in similar occupations (Roscigno and Preito-Hodge 2021). Implicit bias is also an issue among law enforcement, as it is in the broader American population. Studies have found that implicit bias plays a role in decisions of whether officers will use deadly force (Fridell and Lim 2016).

Racism and discrimination have a direct role in creating explicit and implicit biases, which is evident when looking at the history of the institution of policing. Historically, in both the North and the South, police have been used as a tool of social control to manage “unruly” populations. In the North, police intended to control the growing poor European immigrant population and quell labor protests. In the South, the earliest manifestations of police were slave patrols. While these institutions became more bureaucratic over time, looking more like northern police agencies, they still enforced Jim Crow laws and were not afraid to beat and arrest anyone who dared protest these racially discriminatory laws and practices. Given this history, it is not surprising that there is distrust between black communities and police departments. In this next section, we’ll examine the role of institutional racism in the criminal justice system by examining mass incarceration.

7.4.2 Mass Incarceration and the New Jim Crow

The War on Drugs and its associated policies drove massive increases in prison populations. Between 1980 and 2010, the U.S. prison population quintupled. The population only began to decline slightly in the early 2010s. As of 2019, the United States still imprisoned more than 2 million people in prisons and jails. Mass incarceration refers to the overwhelming size and scale of the U.S. prison population. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, but how did this come to be the case?

The War on Drugs is one of the major drivers of the prison population in the United States. In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs, dedicating increased federal funding and resources to quelling the supply of drugs in the United States. This war continued to ramp up through the 1980s and 1990s, especially as crack cocaine became a growing concern in the media and public sphere. Crack cocaine was publicly portrayed as a highly addictive drug sweeping its way through America, allowing politicians to capitalize on this hysteria and pass policies that rapidly increased the prison population. Even so, the vast majority of arrests and enforcement were not of high-level, violent dealers but, more often, small-time dealers or people struggling with addiction. In fact, during the 1990s, the period of the largest increase in the U.S. prison population, the vast majority of prison growth came from marijuana arrests (King and Mauer 2005).

The 1980s and 1990s were also an era where states turned to partnerships with private companies to meet the booming demand for facilities, leading to the rise of private prisons. Private prisons are for-profit incarceration facilities run by private companies that contract with local, state, and federal governments. The business model of private prisons incentivizes them to keep their prisons as full as possible while spending as little as possible on care for inmates. Down 16 percent from its peak in 2012, private prisons still held 8 percent of all people incarcerated at the state and federal level as of 2019 (The Sentencing Project 2021). Still, it is essential to note that the use of these facilities varies by local context. For instance, Oregon has no private prison facilities in the state, while Texas has the highest number of people incarcerated in private prisons.

From the inception of the War on Drugs, racial biases were at the center of these policy changes. For instance, one of Richard Nixon’s top advisors John Erlichman explicitly admitted to this in a 2016 interview:

You want to know what this [war on drugs] was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did. (Baum 2016)

Political sociologists have also traced this back to the so-called Southern strategy. The Southern strategy is a Republican party political strategy to get white voter support through explicitly or implicitly coded racism against black Americans. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Republicans in the South mobilized seemingly race-neutral “tough on crime” appeals to draw support from southern white voters to pass policies like mandatory minimums, sentence enhancements, and other anti-drug policies. These policies impacted the incarceration rate for black Americans compared to white Americans.

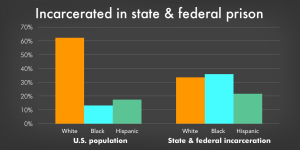

Even as the racial gap in incarceration has narrowed in recent years, the U.S. disproportionately incarcerates black Americans. While black Americans make up 13 percent of the population, they make up over 30 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). Similar trends exist among Latino Americans: while Latinos comprise 16 percent of the U.S. population, they account for over 20 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). In contrast, while white Americans comprise 64 percent of the population, they only make up 30 percent of those incarcerated (Gramlich 2019).

This network of policies and unequal institutional practices led to what scholar Michelle Alexander terms The New Jim Crow. The New Jim Crow refers to the network of laws and practices that disproportionately funnel black Americans into the criminal justice system, stripping them of their constitutional rights as a punishment for their offenses in the same way that Jim Crow laws did in previous eras. Because of these new mass incarceration policies, a new iteration of the racial caste system has emerged: one where black Americans can legally be denied public benefits, housing, the right to vote, and participation on juries because of a criminal conviction.

7.4.3 Intersectionality of Criminal Justice Issues

While racial disparities are one of the most pressing and continuing concerns in the criminal justice system, other marginalized groups face similar institutional inequalities. Recently, there has been an uptick in incarceration rates of women and folks who identify as part of the LGBTQIA+ community. Between 1980 and 2019, the number of incarcerated women increased by more than 700 percent (The Sentencing Project 2022). While the United States incarcerates more men than women, the rate of growth of women’s incarceration has been twice as high as that of men since 1980 (The Sentencing Project 2022).

This increase in women’s incarceration is also directly connected to the disproportionate involvement of the LGBTQIA+ population in the criminal justice system. As of 2019, gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals were over two times as likely to be arrested in the past 12 months than straight individuals (Jones 2021). This disparity particularly impacts lesbian and bisexual women, who are four times as likely to be arrested than straight women (Jones 2021). The high rates of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people behind bars can, in part, be attributed to the longer sentences courts impose on them (Meyer et al. 2017). Transgender individuals also report high arrest and incarceration rates and uncomfortable encounters with the police, with one in six transgender individuals having spent time incarcerated (Grant et al. 2011).

Individuals marginalized by their sexual or gender identity may also face issues when incarcerated. These groups are more likely to be sexually victimized while incarcerated, placed into solitary confinement, and report current psychological distress (Meyer et al. 2017). Similarly, transgender and gender nonconforming individuals lack the same civil rights protections as other groups, which leads to poor treatment in incarceration facilities. For instance, President Trump revoked Obama-era federal guidance, which stated that people who are transgender and incarcerated should be held in facilities matching their gender identity and have access to gender-affirming healthcare services. Then, when President Biden took office, he again reversed back to the Obama-era guidance. This reversal from administration to administration is just one example of how contested federal and state political issues directly impact the lives of individuals.

Finally, the criminal justice system has significant issues with how it addresses mental health issues. In terms of policing, people with mental health issues are more vulnerable to experiencing violence at the hands of police. In 2015, 27 percent of police shootings involved a mental health crisis (Oberholtzer 2017). These inequalities by ability—whether due to disability or mental illness—are pervasive throughout the criminal justice system, including in incarceration.

Jails and prisons have been called modern-day asylums because of the high concentration of individuals with mental illnesses. About one-third of people in all federal or state prisons have been diagnosed with a mental illness, most of whom are not receiving treatment (Wang 2022). In some areas, these issues are even more acute. For instance, in Chicago’s Cook County jail, nearly 50 percent of the people incarcerated had some form of mental illness (Cook County Sheriff’s Office 2022). Incarceration facilities rarely have resources to address these mental health needs. More than 60 percent of people with a history of mental illness do not receive mental health treatment while incarcerated in state and federal prisons (Bronson and Berzofsky 2017). Even those on treatment regimens before incarceration often cannot continue that treatment once incarcerated. Over 50 percent of individuals taking medication for mental health conditions at admission did not continue to receive their medication once in prison (Reingle Gonzalez and Connell 2014).

It’s important to remember that we cannot talk about how identity impacts individuals’ experiences without taking an intersectional approach to these conversations. For instance, black, Indigenous, and Latino transgender people have significantly higher incarceration rates than white transgender people (Jones 2021). This is just one example of how identity is intersectional. To better understand how the criminal justice system impacts people, we must look at all of the different aspects of their identity—gender, race/ethnicity, class, sexuality, citizenship, ability, and other forms of group membership.

7.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Race, Identity, and the Criminal Justice System

First paragraph on criminal justice system in “Race, Identity, and the Criminal Justice System” modified from “7.3 Crime and the Law” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-3-crime-and-the-law

“Race, Class, and Crime” paragraph 1 sentences 2-4 and paragraphs 2-4 modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

Figure 7.7. “Incarcerated in State & Federal Prison” © the Prison Policy Initiative. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 7.8. “Among individuals who have any contact with the police, people of color disproportionately experience the use of force” © the Prison Policy Initiative. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

All other content in this section is original content by Alexandra Olsen and licensed under CC BY 4.0.