10.2 Sexuality

In sociology, sexuality is studied and described in ways that look at sexual attitudes, norms, practices, and social implications. Sexuality is commonly viewed as a social construct, something that societies create and give meaning to that can change and evolve. As you learned in Chapter 4, humans make meanings collectively and we are socialized into the norms that are prevalent in a society early in our lives. Sexuality is also viewed as a cultural universal, meaning that it has existed and does exist in most societies and cultures throughout the world and throughout time.

What we view as “normal” in terms of location, time, age, culture, and many other things changes over time. For instance, if you live in a very liberal and accepting area of society, your understanding and acceptance of sexuality may look very different than if you live in an area that is much more conservative and less accepting of anything outside the sexuality norms. Being open about one’s sexuality can be dangerous in one space, and celebrated in another.

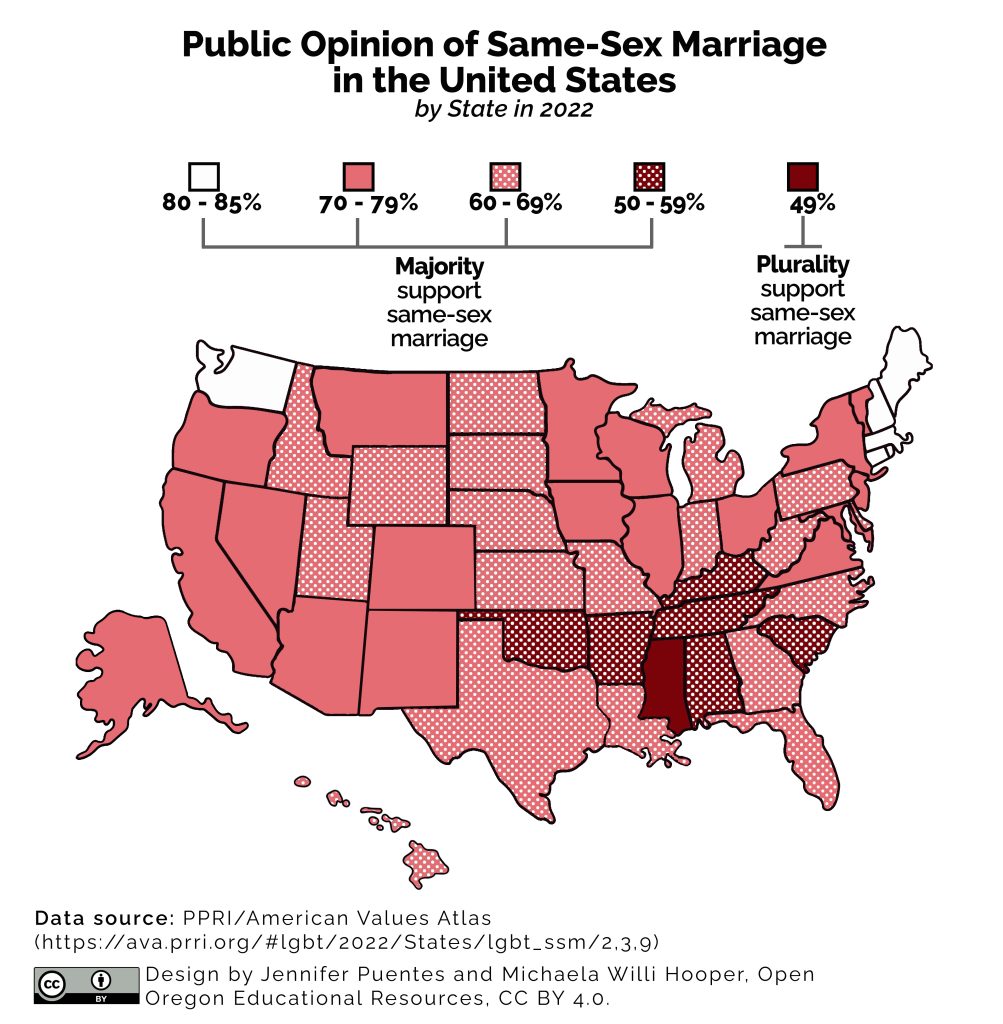

Let’s take a closer look at the relationship between sexuality and marriage. For a long time, legal marriage was not a possibility for everyone. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violate the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution in Loving v. Virginia. Forty-eight years later in 2015, with Obergefell v. Hodges decision the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment requires all states to grant same-sex marriages and recognize same-sex marriages granted in other states. You will learn more about this important decision in “Activity: Same Sex/Same Gender Marriage.” Prior to the Supreme Court ruling same sex marriage was legal, but only in certain states which also did not guarantee legal rights federally. Massachusetts was the first state to grant same sex marriages back in 2004, but that had many barriers to equal protection under the law federally. Congress recently passed the Respect for Marriage Act that allows recognition of all marriages in all states, but does not necessarily protect same-sex marriage if the Supreme Court overturns Obergefell case that made it legal federally (see this NPR article for what that means). But we are still hearing whispers and concerns of the possibility of the Supreme Court overruling this, in light of Roe V Wade being overturned, which would be catastrophic for the LGBTQIA+ community (Webber 2022). According to recent Gallup polls, overturning the Marriage Equality Act goes against public perspectives which demonstrates that most of Americans support gay marriage by a significant percent (Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 This map shows public opinion of same-sex marriage in the United States by state and Washington, D.C. in 2021. Figure 10.2 Image Description.

More information and data on same sex marriage and public opinion can be found in this recent Gallup poll

10.2.1 Activity: Same Sex/Same Gender Marriage

The U.S. Supreme Court decision on Obergefell V. Hodges created equal access to marriage for gay men and women in 2015. To learn more about this decision, please watch the video Obergefell v. Hodges Explained and come back to answer the questions below:

Figure 10.3 Obergefell V Hodges Explained [YouTube Video]

- Considering marriage and what that means to you and your family, and the right to marry the person you love, what has made our society have limits on who can access that right? Do you think this should be in question? Keep in mind that women did not have a say in these decisions for most of history.

- The four dissenting judges cited that states should independently decide whether the state should allow same sex marriages based on popular votes. What effects do you think this would have federally? What about in states that would vote no?

- After the decision to overturn Roe V. Wade, decisions about access to abortions are left up to individual states. What impact can you imagine would happen if the Obergefell V Hodges decision could be overturned? What rights would same sex couples lose if some states decided their marriage was illegal? How does the Respect for Marriage Act support couples?

10.2.2 Sexuality and Sexual Orientation

Sexuality is the sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviors individuals have towards other people. Sexual Orientation refers to enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. In Chapter 9 you learned the term cisgender, which refers to those who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth. We can apply this concept to our understanding of sexualities. For example, a cis woman who is attracted to cis men would likely be categorized as the default heterosexual, or a man who is attracted to other men would likely be homosexual, or gay. There is an ever growing list of sexual orientations and acknowledging the need for each person to define their own identities is highly important, including the identity of not having sexual attraction to others, or asexual.

As sexualities are diverse and definitions of sexuality change over time, it can be difficult to consistently study sexuality in the United States. The ability to accurately measure sexualities and understand how individuals’ identify is difficult given that what sexuality means varies in different time periods and in different cultures. Sexuality is also understood and interpreted differently by different groups. Sociologists and other researchers conducting research on sexualities have the difficult task of finding ways to make sure their research reflects the diversity of identities and experiences in the LGBTQIA+ population.

Let’s start by examining issues related to the definition of sexuality. Broad umbrella terms can be used by different generations to convey different meanings.Younger generations may use the term “gay” to mean many different things (i.e. lesbian, gay, queer, bisexual, pansexual…etc.) whereas the term was commonly understood previously as being men who were attracted to men and not an umbrella, or catch all term. When a survey asks about sexuality there may be many different interpretations to the terminology used. Also for those who identify as asexual, but consider themselves gay, questions about intimate relations and sexual behaviors are less relevant.. Another example that problematizes our ability to accurately collect survey research with this population could be someone who identifies as queer sexually, but only dates people of the same gender (like a woman who only dates cis-women, or only dates trans-women). A survey simply asking about sexual practices may miss out on large aspects of experiences. Or what about someone who identifies as heterosexual/straight, but has sexual relations with other genders privately or for money? There are many other examples, and these may seem simplistic, but the variations on what sexuality is in general, and what terminology for sexualities means varies across age, regions, social groups, and identity.

Another issue with understanding sexuality in context of numbers and population concerns social stigma and whether respondents would feel safe or are willing to disclose their identities. Even if a survey is random and anonymous, it can feel uncomfortable or even dangerous for some to claim a sexuality other than heterosexual. Some may not be in a place where they are accepting of their own identity given social norms and the expected sexuality, which we will cover in the next section. Overall, the estimates from studies and national surveys are valued as being relatively representative of the overall population that identifies as certain sexualities, but many believe that they are underestimating the LGBTQIA+ population (Powell 2021).

Many argue that sexuality is chosen and those who are not straight are just choosing to be, but there are unknown biological factors that support it as biology and not choice. Research suggests that it is not uncommon for individuals to experience attraction to someone of their same gender during adolescence (Stewart et al. 2019). For those who realize their crushes or attractions fall outside of the binary hetronormative model, their feelings can be confusing, scary, and may cause shame due to heteronormative standards.

As a society we place an enormous amount of value on the relationships we have with others, as individuals, groups, and society. We see this trend in books, tv shows, movies, music videos, photos, paintings, and many other aspects of society. Think of the last three movies you watched and imagine how many sexual or romantic relationships were in them. What types of relationships were they? What sexualities were represented? While we are starting to see more examples of diverse representations, most visual and textual representations of relationships center on heterosexuality, leading to the continuing dominance of heteronormativity. Heteronormativity is a concept that suggests heterosexuality is a preferred sexual orientation and functions by assuming a gender binary.

10.2.2.1 Heteronormativity/Compulsory Heterosexuality

Heteronormativity and compulsory heterosexuality are concepts that help us understand how social norms often intersect with other dimensions of our lives, like sexuality. Heteronormativity is the idea that heterosexuality is the preferred or “normal” mode of sexual orientation (Harris and White 2018). Compulsory heterosexuality refers to the notion that our patriarchal and heteronormative society creates an environment where heterosexuality is assumed. Adrienne Rich, an American poet and feminist wrote about how women are socialized to devalue and minimize their relationships with other women and encouraged to prefer relationships with men (1980). Societal expectations for both gender and sexuality shape the ways in which we interact with others.

Let’s take a moment to examine messages about sexuality in something that may be iconic from your childhood – Disney movies. Disney offered us messages about love as this wonderful, magical, and expected idea where the prince sees the princess and they fall madly in love with lights, music, sparkles, and no idea who the other one really is. This magical immediate process between a man and a woman is implied as an ideal fantasy throughout many of our childhoods. The woman is lovely with flowing hair and perfect curves, the man is strong and saves the day with brawn and, of course, also perfectly masculine hair. We are raised with this idea through tales in books, movies, and all over visual and consumer spaces. So what is expected of humans? We should fall in love with the ideal of the opposite sex, this idea is institutionalized into so many norms, rituals and expectations that we don’t even really see it most of the time, but it also reinforces and adds to the dynamics of power and influence and how that is perceived and conceptualized in the United States.

From a very young age we are taught these norms through all institutions of our lives, therefore from childhood to adulthood, the understanding is that if you are not heterosexual then you are not “normal” or need to be fixed, changed. Although we do see more of this changing in some parts of society, such as recent films with gay characters, trans characters, it is still not a societal norm and each time these things occur there is a social backlash against them. What happens when young people learn heteronormativity as such a big part of their lives at such a young age? See figure 10.4 for something we commonly see if children’s artwork and doodles.

Figure 10.4 A child’s sidewalk drawing of what appears to be a female with a long veil and dress and a short haired figure with the words “the end.” This idea is so deeply embedded in society that boy meets girl, they fall in love, they get married and live happily ever after that it appears everywhere.

What then happens if we are not heterosexual and cisgender? If we go back to children’s socialization, we are then mocked, viewed as outsiders, or become the butt of a strange and insulting joke. This is the basis of heteronormativity and compulsory heterosexuality. Did anyone who is straight and cis ever have to come out as such? Ever asked “maybe you just haven’t met the right woman/man yet,” or “you just haven’t slept with the right person” as a straight person? Find the heterosexual questionnaire here and think about how strange it really is in reverse. In reality also violence, or fear and suggestion of, harassment, bullying, rejection are the outcomes if one does not conform to the compulsive heteronormative or heterosexual ideas. This also relates to gendered expectations in many ways which will be visited in this text in Chapter 9.

10.2.3 Sexual Attitudes and Practices

We see some common themes in sexual attitudes across the US. What is seen and viewed as acceptable and how the social construction of sexuality occurs in different societies and cultures affects sexual practices and expectations for behavioral norms based on sex and gender.

10.2.3.1 Sexuality around the World

When we explore sexuality around the world it can be especially helpful to apply a social construction lens. That is, we can say that gender difference is socially constructed; or through our interactions, we create gender roles and norms that determine how we are expected to interact as gendered people with sexual expressions. So in this case, roles are the parts people play as members of a social group according to our gender. Norms prescribed to the behavior of that group are those that are ideal or appropriate. Gender or sexuality behaviors that live outside those expectations can be considered unacceptable, or taboo by dominant groups of a society for a person of that specific gender.

Cross-national research on sexual attitudes in industrialized nations reveals that normative standards differ across the world. For example, several studies have shown that Scandinavian students are more tolerant of premarital sex than are U.S. students (Grose 2007).

Of industrialized nations, several European nations are thought to be the most liberal when it comes to attitudes about sex, including sexual practices and sexual openness. Sweden, for example, has very few regulations on sexual images in the media, and sex education, which starts around age six, is a compulsory part of Swedish school curricula. Switzerland, Belgium, Iceland, Denmark, and The Netherlands have similar policies. Their more open approach to sex has helped countries avoid some of the major social problems associated with sex. For example, rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease are among the world’s lowest in Switzerland and the Netherlands – lower than other European countries and far lower than the United States (Grose 2007 and Dutch News 2017). It would appear that these approaches are models for the benefits of sexual freedom and frankness. However, implementing their ideals and policies regarding sexuality in other, more politically conservative, nations would likely be met with resistance.

10.2.4 Sexuality in the US

A good understanding of Americans’ sexual behaviors comes from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), which was administered to 13,459 Americans ages 15–44 nationwide. Although many people think that males are much more sexually active than females, research shows that the gender differences in heterosexual contact are practically nonexistent (Candra et al 2011).

Studies have shown that one’s religiosity are strongly associated with greater disapproval of premarital sex. Does this mean that religiosity should also be associated with a lower likelihood of actually engaging in premarital sex? The answer is clearly yes, as many studies of adolescents find that those who are more religious are more likely to still be virgins and, if they have had sex, more likely to have had fewer sexual partners (Regenerus 2007). Survey data on adults produce a similar finding: Among all never-married adults in the GSS, those who are more religious are also more likely to have had fewer sexual partners (Barkan 2006). Among never-married adults between the ages of 18-39, never-married adults who identify as very religious are more likely to have had no sexual partners in the past five years and, if they have had any partners, to have had fewer partners. Although it is hypothetically possible that not having sexual partners leads someone to become more religious, it is much more likely that being very religious reduces the number of sexual partners that never-married adults have (GSS, Smith et al 2011).

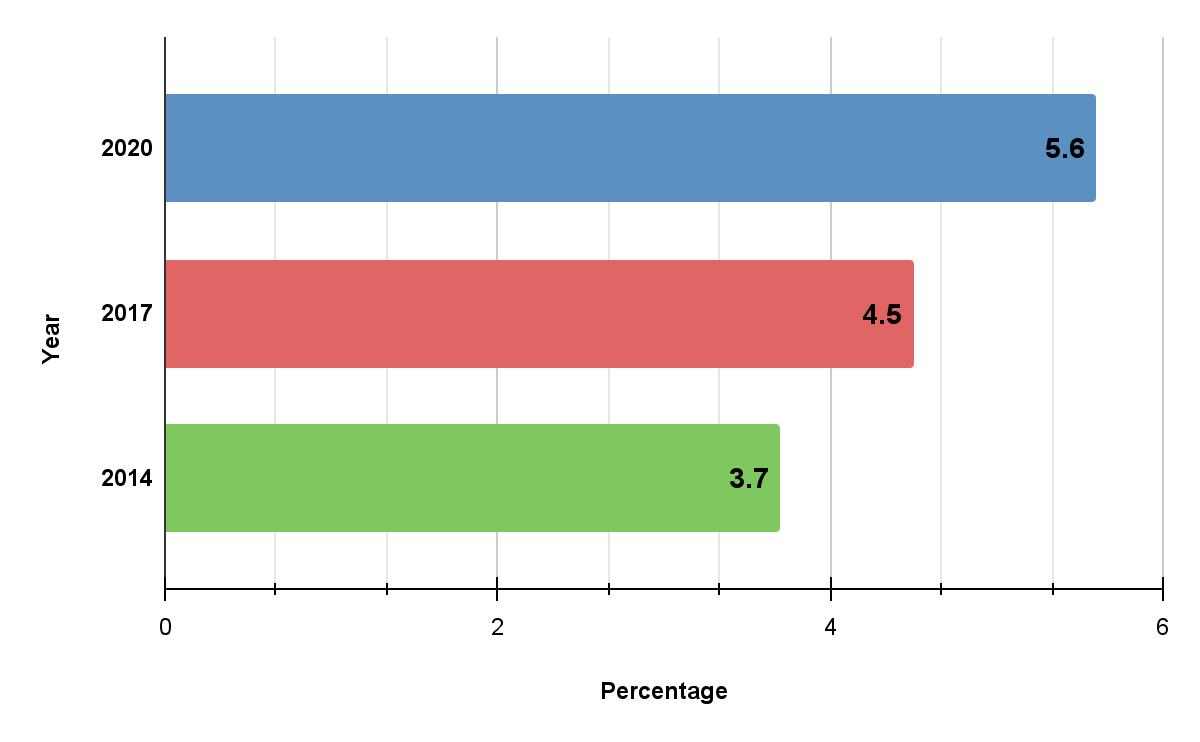

When studying sexuality, behavior is only one part of the larger picture. We just also look at how people construct their identities. The majority of people in the United States identify as heterosexual (US Census Bureau, Jones 2021), or attracted to a sex different than their own – biologically speaking – so this is where we see the norms and behaviors that guide most societal expectations and expressions of sexuality, or socially constructed sexuality norms and behaviors. Remember above we looked at compulsory heterosexuality in the United States? This is a social construction of sexuality, that heterosexuality and heteronormativity are expected and celebrated in the United States, but other norms and behaviors occur around the world. Let’s look at what has changed in the United States and whether that is guiding us to a new space in terms of sexuality. Even though a majority of the population identify as heterosexual there is also an increase in sexual identities other than heterosexual (Figure 10.5), and looking at the why behind that is important.

Figure 10.5 Percentage of Americans, 18 or Older, Who Self-Identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender

The increase in those who identify as a sexuality other than hetero does not mark a shift in attraction, but rather indicates there is more acceptance within society and social dynamics, For example the more we can ‘see’ people like us, the more we are likely to ‘be’ who we are openly. Fifty years ago, in public spaces homosexuals were routinely outcast, harassed, attacked, and even murdered. The fact that this was normative behavior leads us to understand why many would not ‘come out’ to share their sexuality and sexual identity publically. Discrimination, harassment, assault, and judgment continue to be a concern today; however those who identify as ‘not straight’ are much more visible and have many more rights than 50 years ago. A reminder that those who ‘appear’ to be not heterosexual or not ascribe to a binary gender ideal are still at very high risk of assaults and attacks even now and across the United States, more are willing to be open even in light of that fact, which is what makes it more acceptable to come out and be who one is for many.

As you learned earlier in this chapter, heteronormativity significantly impacts our current norms and expectations for both gender and sexuality. These ideas have a strong hold on what is accepted, expected, and normalized. The pressure and assumption of heteronormativity can significantly impact many aspects of our society and our own daily lives throughout our life cycle. We will look at one piece of that in the form of sexual education and how and when sex education is introduced in our society and what it includes.

10.2.4.1 Sex Education

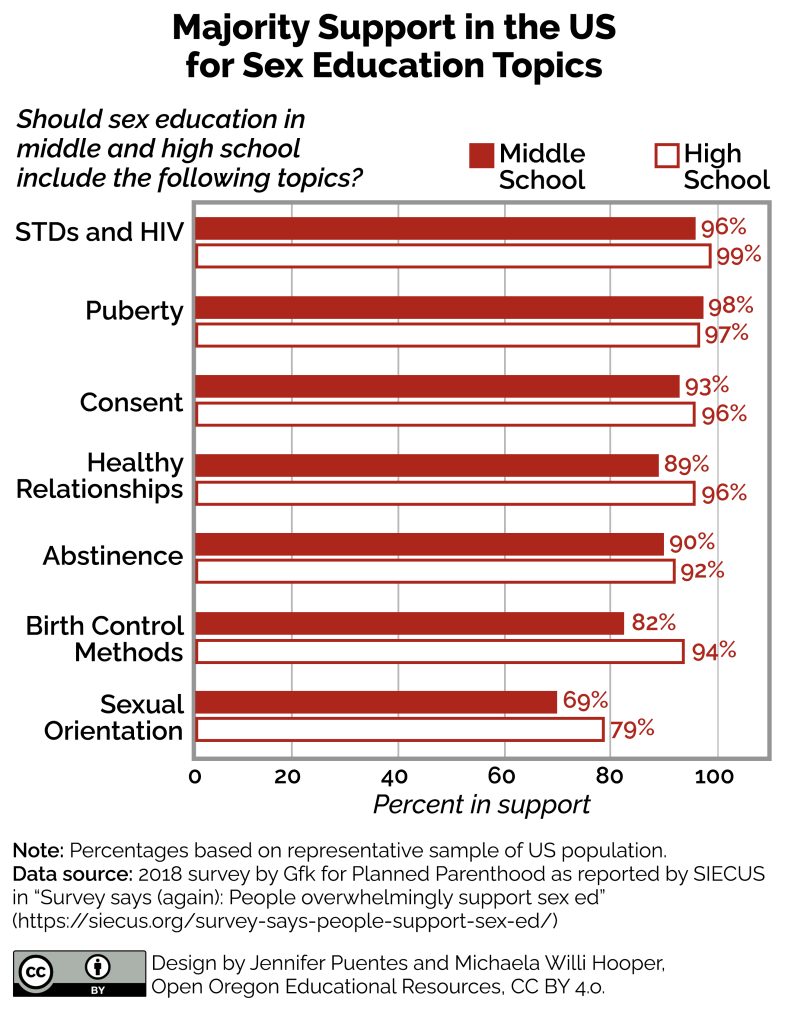

One of the biggest controversies regarding sexual attitudes is sexual education in U.S. classrooms. Unlike many other countries, sex education is not required in all public school curricula in the United States. The heart of the controversy is not about whether sex education should be taught in school (studies have shown that only seven percent of U.S. adults oppose sex education in schools); it is about the type of sex education that should be taught. Much of the debate is over the issue of abstinence as compared to a comprehensive sex education program. Abstinence-only programs focus on avoiding sex until marriage and/or delaying it as long as possible. So they do not focus on other types of prevention of unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. As a result, according to the Sexuality and Information Council of the United States, only 38 percent of high schools and 14 percent of middle schools across the country teach all 19 topics identified as critical for sex education by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Janfaza 2020). Figure 10.6 outlines U.S. adults’ attitudes about what content should be included in a comprehensive sex education program.

Research suggests that while government officials may still be debating about the content of sexual education in public schools, the majority of U.S. adults are not. Two-thirds (67 percent) of Americans say education about safer sexual practices is more effective than abstinence-only education in terms of reducing unintended pregnancies. A slightly higher percentage—69 percent—say that emphasizing safer sexual practices and contraception in sexuality education is a better way to reduce the spread of STIs than is emphasizing abstinence (Davis 2018).

Even with these clear majorities in favor of comprehensive education, the Federal government offers roughly $85 million per year to communities that will drive abstinence-only sex education (Columbia Public Health 2017 a). The results, as stated earlier, are relatively clear: the United States has nearly four times the rate of teenage pregnancy than a country like Germany, which has a comprehensive sex education program.

In a similar educational issue not necessarily related to sexuality, researchers and public health advocates find that young girls feel underprepared for puberty. Ages of first menstruation (menarche) and breast development are continually declining in the United States, but education about these changes typically doesn’t begin until middle school, which is generally too late. Young people indicate concerns about misinformation and discomfort during the informal conversations about the topics with friends, sisters, or mothers (Columbia Public Health 2017 b).

Figure 10.6 This chart shows that a majority of a representative sample in the US think most of these topics (abstinence, birth control, STD’s, healthy relationships, sexual orientation, puberty, and consent) should be included in our educational systems curriculum in sex ed. Figure 10.6 Image Description

Figure 10.6 This chart shows that a majority of a representative sample in the US think most of these topics (abstinence, birth control, STD’s, healthy relationships, sexual orientation, puberty, and consent) should be included in our educational systems curriculum in sex ed. Figure 10.6 Image Description

Sweden, whose comprehensive sex education program in its public schools educates participants about safe sex, can serve as a model for this approach. In 2020, the teenage birthrate in Sweden was 5 per 1,000 births (worldbank.org 2020), compared with 15.4 per 1,000 births in the United States (CDC, 2021). Among fifteen to nineteen year olds, reported cases of gonorrhea in Sweden are nearly 600 times lower than in the United States (Grose 2007).

A sociologist using the sociological perspective would want to look at the correlation between sex ed curriculum and outcomes such as teen pregnancies and STDs. Mississippi has the highest rates of teen pregnancy with 28 births per 1,000 women ages 15-19. What does Arkansas’ sex ed legislation look like? Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Alabama are next in line with around 25 births per 1,000 women ages 15-19 (CDC 2021). What does sex ed look like in those states? Is there a correlation? What other factors could influence teen pregnancy in these states?

In this chapter we introduced concepts related to sexuality and sexual orientation, before going into more depth on sexual attitudes and practices. It is clear that much of our lives is structured through the lens of heteronormativity. This structure of compulsory heterosexuality influences the way sexuality is experienced in the US, including some of the limitations around sex education. Our sexual identity cannot be isolated or separated out from our other identities. As you will learn in “Activity: Intersectional Systems of Oppression,” multiple parts of our identities come together to build our experiences in the social world. Identities related to race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality intersect to shape our experiences, but are also subject to broader power structures that are pervasive in our lives. As you listen to the video in the next section, start thinking about some of the intersecting experiences one may have and how it shapes their ability to navigate the world around them.

10.2.5 Activity: Intersectional Systems of Oppression

Watch this video on anti-violence and how the connections between race, gender, sexuality, etc. are intersecting. Be sure to compact to answer the questions in this activity. Oppression is where power is held by those who are in power, as they state in this video, white supremacy, heteronormative ideals. We can not change the power dynamic of those who are oppressed until we work together and recognize those intersections.

Figure 10.7 “Connecting the Dots: Ending Racism and Oppression [Youtube Video].”

- How does intersectionality apply to your life, and the lives of others you see in your community?

- What steps can we take to recognize the power dynamics and change them?

- How does oppression and power connect to the topics we have covered so far? Sex education? Sexuality and heteronormativity?

10.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Sexuality

“Sexuality” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.2. “Public Opinion of Same-Sex Marriage in the United States” by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from PPRI – The American Values Atlas.

Figure 10.4 Photo use by Heidi Esbensen License: CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Same Sex/Same Gender Marriage” and Figure 10.3 (screenshot) adapted from Obergefell v. Hodges Explained by Zack Attack. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 10.3. “Obergefell v. Hodges Explained” by Zack Attack is licensed under the Standard YouTube License/fair use

Text from “Activity: Same Sex/Same Gender Marriage” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Sexual Orientation definition adapted from Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The first two paragraphs of “Sexuality in the US” are adapted from “Sexual Behavior” by Saylor Academy, Social Problems: Continuity and Change, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Rest of section by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 10.5 CCBY 10.1 Sex, Sexual Orientation and Gender – Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us

“Sex Education” is adapted from “Sexuality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Updated and edited. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

Paragraphs 5-6 of “Sex Education” is adapted from “Sex and Sexuality” by LibreTexts, SOC 300: Introductory Sociology (Lugo), which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Open Stax 3E under CC BY 4.0

Paragraphs 5-6 updated and edited by Heidi Esbensen from

Paragraph 7 by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.6 CCBY 10.1 Sex, Sexual Orientation and Gender – Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us

Figure 10.6. “Majority Support in the US for Sex Education Topics” by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from GfK for Planned Parenthood, as reported in “Survey says (again): People overwhelmingly support sex ed” by SIECUS.

Figure 10.7. “Video 1: Connecting the Dots” by Futures Without Violence is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Image Description for Figure 10.2:

Map shows the 50 states and the percent in support of same-sex marriage by the following ranges:

80-85% in support

- Connecticut

- Maine

- Massachusetts

- New Hampshire

- Rhode Island

- Washington

70-79% in support

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Colorado

- Illinois

- Iowa

- Maryland

- Minnesota

- Montana

- Nevada

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- Ohio

- Oregon

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Wisconsin

60-69% in support

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Indiana

- Kansas

- Louisiana

- Michigan

- Missouri

- Nebraska

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- South Dakota

- Texas

- Utah

- Wyoming

50-59% in support

- Alabama

- Arkansas

- Kentucky

- Oklahoma

- South Carolina

- Tennessee

49% in support: Mississippi

Data: PPRI American Values Survey

Design by Michaela Willi Hooper and Jennifer Puentes, CC BY 4.0.

[Return to Figure 10.2]

Image Description for Figure 10.6:

Image shows bar chart of how people responded to the question “Should sex education in middle and high school include the following topics?” for both Middle and High School

Should sex education in middle and high school include the following topics?” Percent in support:

| Topic | Middle School | High School |

| STDs and HIV | 96% | 99% |

| Puberty | 98% | 97% |

| Consent | 93% | 96% |

| Healthy Relationships | 89% | 96% |

| Abstinence | 90% | 92% |

| Birth Control Methods | 82% | 94% |

| Sexual Orientation | 69% | 79% |

Note: Percentages based on representative sample of U.S. population.

Data source: 2018 survey by Gfk for Planned Parenthood as reported by SIECUS in “Survey says (again): People overwhelmingly support sex ed” (https://siecus.org/survey-says-people-support-sex-ed/)

Design by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper,

Open Oregon Educational Resources, CC BY 4.o.