10.3 Learning the “Rules” of Sexuality

Through the process of socialization you learn many of the unspoken rules about what behaviors and attitudes are acceptable in your culture. While you learned more generally about socialization and gender socialization earlier in this book, now we’d like to turn our focus on sexuality. Our socialization into sexuality is no different than other forms – it begins at birth and continues throughout our lives. A quick review of baby clothing and items, such as bikini bathing suits for female babies, high heels, and sexually explicit shirts, reveals that the desire to teach children about living as sexualized beings starts very early. This also applies to gendered ‘rules’ in spaces such as being submissive, the ‘rules’ around sexuality typically follow the rules of gendered ideals in the United States. We can see in research around pornography (Rostad 2019, Guggisberg 2020) that there are very common themes around those sexual scripts and the gender scripts. Further sexual violence is being seen as a sexual script and rule, leading to the the normalization and prevelance of sexual violence. We will discuss this more in the section “Sexual Assault and Sexual Violence.”

Learning the “rules” of sexuality connects to the social norms that promote heteronormativity. This creates pressures for those who do not identify as heterosexual to hide identities that do not fit the ideals prevalent in our society. As you learned at the beginning of the chapter, many areas of the U.S. are having debates and creating laws making it illegal to discuss any type of sexuality in schools. However, these debates and rules are not equally applied to all partnerships. For example, there is no expectation that anyone will stop discussing relationships between a man and woman or a husband and wife in those spaces. The reality As you learned in the last section, sex education doesn’t really cover a diversity of sexual relationships, much less are they open topics in schools across the United States and yet we still don’t seem to grasp why individuals in the LGBTQIA+ community are at higher risk of mental health struggles and suicide (Trevor Project, 2021).

How do people learn the “rules” of sexuality? Our actions and interactions are guided through sexual scripts.

10.3.1 Sexual Scripts

A sexual script is a phrase that refers to the social rules that guide sexual interaction (Gagnon and Simon 1973). Sexual scripts derive from our culture and provide us with a set of “rules” to follow for sexual behaviors. In other words, sexual scripts provide us with information about with whom, when, where, and in what order we should have sex. We often follow sexual scripts most closely when we first become sexually active or with new partners as they help ease the process of social interaction. We can start to predict what behaviors might be expected first and follow. For example, you are likely to expect that you would kiss someone on the mouth prior to participating in groping or touching genitals. The predictability of sexual scripts follows expectations we have as you move from less intimate to more intimate behaviors.

The sexual behaviors we participate in because of the sexual scripts we are familiar with are also embedded in a larger power dynamic. Sexual scripts are gendered (Endendijk et. al 2020).Given the conflation with masculinity and power, the masculine role in sex is perceived as the assertive role. Similar to the ideas shared about emphasized femininity in Chapter 9, the feminine role is perceived as primarily responsive. This conflation of sexual power, desire, and masculinity leads to the push-and-resist dynamic (Gavey 2005). The push-and-resist dynamic refers to the idea that it’s normal and expected for men to push for more sexual activity, while women are tasked with stopping or slowing sexual activity. Rather than focusing on consent, there is a gender imbalance as one gender is expected to push for activity, while another gender becomes the keeper of consent. In practice, we know that masculinity and femininity can be performed by anyone, so we don’t always think of this as directly tying to a particular sex but rather reflecting who might be participating in masculine or feminine roles.

To this point, we’ve mostly discussed sexual scripts in terms of heterosexual relationships, but sexual scripts are part of gay culture too. Sexual scripts for gay men in the U.S. tend to differentiate between the roles of tops, bottoms, and versatiles (Moskowitz and Roloff 2017; Moskowitz et. al 2021). These roles are gendered where topping is perceived as masculine and bottoming as feminine. Given the dynamics between sex, gender, and power in the U.S., people tend to think of topping or men who identify as tops as not only masculine but more dominating. Men who identify as bottoms often have to deal with stereotypes where they are perceived as feminine. Other gay men will avoid replicating sexual scripts or reject labels completely by adopting a versatile identity and adopt both penetrative and receptive roles in their sexual encounters. While there is less research lesbian sexual scripts, we know that women who have sex with other women have the least scripted sexual relationships. Research suggests that lesbians do not have a single standard they use to define encounters as sex, unlike many of their heterosexual counterparts who often use penile-vaginal intercourse as a way to define the occurrence of a sexual encounter (Sewell et al 2017).

10.3.2 Sexual Assault and Sexual Violence

Sexual violence is not part of all societies. The normalization of sexual violence is facilitated through some environments, often referred to as rape cultures. Within these environments the culture justifies, naturalizes, and may glorify sexual pressure, coercion, and violence (Marcus 1992, Pascoe and Hollander 2016). For examples of how this sexual violence is depicted in our popular culture you can refer to the images in Figure 10.8.

Sexual violence is not only about physical issues, but also language, norms and everyday behaviors. Sociologists examine difficult topics like assault and violence to better understand underlying issues like how these behaviors are part of our current culture. As we have seen throughout the gender chapter, gender norms are something that lie underneath most institutions in our society, including power structures and institutional discrimination, sexual violence is no different.

Figure 10.8 A series of ads from Dolce and Gabbana that have since been banned, they explicitly depict sexual violence in several ways.

In the United States, (Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics | RAINN) sexual assault and rape is statistically underreported and depending on what measure, definitions and how the data is examined varies greatly. According to RAINN, there are 463,634 victims of rape and sexual assault each year of those that are age 12 and older. Females are at the highest risk and have higher percentages of reported and assumed assaults. Males are also impacted with about 1 out of 10 reported rape victims being males. Also transgender, genderqueer, and gender nonconforming students are at higher risk of rape and sexual assault than cis identifying men and women.

The rates of assaults are indicative of larger systemic issues in society. We can look back to our environment and dominant culture that is valued such as patriarchy. It creates these norms through matters of dominance and control, hegemonic masculinity, thus maintaining the status quo. We see this through normalization of sexual violence in the media, socially, and politically, as we see in high profile cases where the ‘boys will be boys’ narrative is prominent (a few recent examples are court cases involving Brett Kavanaugh and Donald Trump). One way rape culture is normalized is that young girls and women are taught to minimize discomfort and advances to avoid hostile situations with men to protect themselves. Normalizing this behavior occurs in several ways. Here are a few phrases that may seem familiar:

- It wasn’t “legitimate rape” – didn’t finish, she liked it, they knew them

- It’s not rape if she didn’t say ‘no’ – how hard someone fights back or not, how verbal she was or was not about it at the time

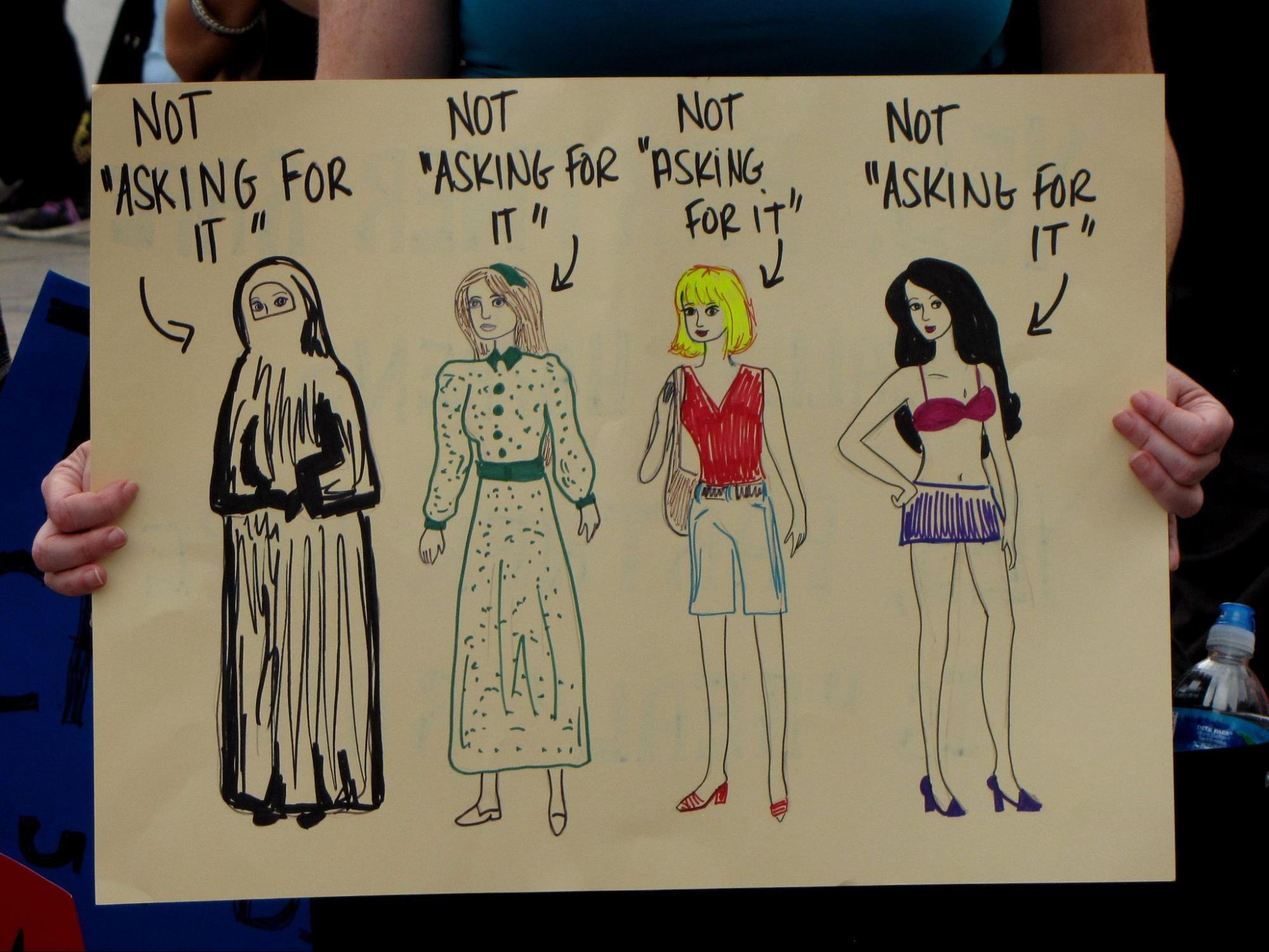

- It was her fault – what she was wearing, how she looked, she was a tease, etc.

- She was drunk – she should have been more responsible

- Rapists are monsters – it was just one horrible person

Read this article for more on the things women do that we don’t really think about: The Thing All Women Do That You Don’t Know About

The ideas and norms that are part of rape culture also serve as barriers to reporting sexual violence. In U.S. culture there is a great deal of uncertainty around the types of consequences perpetrator of sexual violence will experience. In addition to the fear that people won’t be believed when they report, they can also look to how sexual violence is treated in the news and social media. Some concerns survivors may have around reporting center on:

- Belief that men just can’t help it

- Lack of trust in authority figures – will they do anything?

- Not wanting to make a ‘big deal’ out the incident

- Embarrassment – “I must have done something to deserve it”

- Other girls lack of support – “suck it up”

Gender inequality and assumptions are connected to all of these, but how? You will see how we can challenge the normalization of this in the Activity at the end of this section with a TedTalk by Susana Pavlou titled “Challenging Normalization of Sexual Violence Against Women”. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports that the majority of rapes and sexual assaults perpetrated against women and girls in the United States between 1992 and 2000 were not reported to the police. Only 36 percent of rapes, 34 percent of attempted rapes, and 26 percent of sexual assaults were reported.

Sexual violence is not about sex per se, it is about control and dominance. Power: used as a way to dominate, not really about sex, just control. Uses sex as a weapon, or tool to accomplish control and power – think of the images below in 10.9 to connect how violence is more about excusing the behavior and blaming the victims, who can be anyone.

Figure 10.9 Photos of people of differing ages, status, race, and identities showing that anyone can be affected by sexual assault and violence.

Sexually explicit video games and online pornography fuel the fire, so to speak, as well as create norms around behavior, which in those cases can be quite negatively impactful. The majority of pornography historically is made by men and for men, thus replicating norms of sexual violence and dominance. Research concluded that explicit video games and online pornography lead to increases in sexual violence and harassment. They reinforce norms and acceptance of such behavior, they are readily available for many to see, there is little regulation on them outside of content warnings, and it makes for less stigma around playing explicit video games and watching pornography. Again since most of these are made by men, for men, they can be deemed as an expression of the norms and of expression of wants, desires, expectations, and fantasies.

Given the discussion of violence and desires for sexual domination expressed by men for men through the above platforms, research also shows that men are also victins of sexual violence, 1 in 26 men reported completed or attempted rape at some point in their lifetime, compared to 1 in 4 women. In other words, about 14 percent of reported rapes involve men or boys, and that 1 in 6 reported sexual assaults is against a boy and 1 in 25 reported sexual assaults are against a man. There are many barriers to reporting for women and men, but specifically for men there is a culture of silence, based on several factors, one of which being personal shame in response to cultural norms of strength and dominance. Men are not ‘supposed’ to be victims, especially in the space of sexual relations. According to data and research, when asked about experiences in the last 12 months, men reported being “made to penetrate”—either by physical force or due to intoxication (1.3 percent according to 2015/2016 CDC data). Within all of this the primary understanding is that as a society, sexual harassment and sexual violence are normalized in many realms, it is a form of dominance and control over others, and there are significant barriers to reporting, leaving, and coping with the trauma after an event. Victims are criticized, ostracized, not believed, blamed and made to feel as if the events were untrue, over-exaggerated and in some way their fault, either by not being strong enough, not saying no, or because of the way they were acting or how they were dressed. In Activity: Understanding the Normalization of Violence (Figure 10.10) you will examine society through a different lens to understand more about how violence is normalized in our culture. Our responses to acts of violence send messages about what types of behaviors and language are acceptable. Please keep in mind that rates of sexual violence in the LGBTQIA+ community are the same or higher than in heterosexuals.

Sexual violence will be experienced by about half of trans individuals and bisexual women during their lifetimes. Their experiences relate to having higher risk factors such as poverty, stigma, and marginalization which leads to higher rates of sexual assault in populations. Another factor that contributes to high rates is hate motivated violence, which can often take the form of sexual assault and sexual violence. There are also high rates of intimate partner violence and sexual assault from partners within the LGBTQIA+ community. Research suggests that stigma of these relationships as well as hypersexualization of the community creates a double standard and contradicting social norms which adds to possible internalized homophobia and shame about the relationships.

Data from national CDC survey analysis (National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey) shows that bisexual women are at much higher risk in their lifetimes, in some cases double, for all forms of sexual violence compared to heterosexual women. The same trend is seen when comparing bisexual women and lesbians, although slightly less drastic prevalence. Additionally, lesbians are more likely than heterosexual woman to face sexual violence. These same trends are seen with bisexual men and gay men with heterosexual men experiencing lower rates of sexual violence. You might be wondering why we see these patterns in LGBTQIA+ populations. Some studies have shown that it may be linked to distrust and stereotypes of bisexuals, that they are incapable of having monogamous relationships, there is also the likelihood that homophobia plays into this systemic issue. We can see with this trend of transphobia and homophobia in the rates that are found also for trans individuals, the 2015 Transgender survey showed that almost half of trans people are at some point in their lifetime sexually assaulted, with higher rates in those who are trans and BiPoc. We also see a trend that those who identify with the LGBTQIA+ community are less likely to receive access to services, or be denied services due to their sexual or gender identity. This also leads to even more hesitancy to report or seek care or services increasing the barriers discussed above for those who are LGBTQIA+.

10.3.3 Activity: Understanding the Normalization of Violence

Figure 10.10 TedTalk Challenging normalization of sexual violence against women | Susana Pavlou | TEDxUniversityofNicosia

- What was one thing that really stuck out to you about this video?

- Susana Pavlou discusses some myths around sexual violence. Have you heard, witnessed, or experienced these myths in your experiences with society? How prevalent are they?

- What suggestions does the speaker present for solutions/decreasing sexual assault? How do you think we can decrease sexual assault?

10.3.4 Orgasm Gap

The orgasm gap is exactly what it sounds like, the difference between reported orgasms by gender. Based on data from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior from 2018, 91 percent of men reported they had an orgasm at their most recent sexual event, yet only 64 percent of women reported they had an orgasm at their most recent sexual event. You might be wondering what drives this difference in sexual pleasure? Social factors are at play including double standards, sexual norms, scripts, and social pressures.

The double standard relates to women being willing participant is sexual acts, but not too willing (further discussed in the next section on hookup culture). This leads to a situation where women attempt to ‘fulfill’ their sexual partner’s needs with minimal focus on their own pleasures. Similar to the sexual norms of satisfying men in U.S. culture, sex is perceived as something for men to enjoy and women to participate in for that pleasure. We saw this in the discussion of pornography and how it shows dominance of women for a man’s pleasure almost solely.

How does this play into LGBTQIA+ relationships? Do the same norms situate themselves within relationships in some way? Research shows that heterosexual men usually or always orgasm during sex (95 percent), but also gay men (89 percent), bisexual men (88 percent), and lesbian women (86 percent) stated high rates or orgasm while being sexually intimate, whereas bisexual woman and heterosexual women fall short with 66 percent and 65 percent respectively. Why might we see a disparity in orgasms among women who have sex with men? Research suggests that women’s experiences are connected to factors outside of the act of intercourse. Women who orgasm more in intimate relations receive more oral sex, longer sessions, are more satisfied within the relationship, speak up about what they want and include more intimate pieces (kissing, build up, manual stimulation, etc.) (Frederick, John, Garcia, and Lloyd, 2018). If social norms do not encourage women to be vocal about the types of desires they have or if their needs fall outside of expected sexual scripts, women’s need are likely to go unfulfilled in sexual encounters.

10.3.5 Hookup Culture

The hookup culture is when individuals ‘hook up’ for sexual relations outside of romantic relationships. A majority of the research on hookup culture occurs on college campuses or with college age individuals. A similarity across research findings is that there continues to be a double standard for men and women. Social stigma surrounds women’s sexuality in ways that are restrictive. This has been shown in many studies in varying college situations (Armstrong, Hamilton, England, 2010; Kettrey, 2016; Cera, Ford, and England, 2017). Both women and men police these actions.

Hookup culture sets up gendered expectations for both women and men. There are three ways that the hookup culture is significantly gendered: 1) orgasm gap, 2) men tend to initiate hookups, 3) double standard. With the orgasm gap, women report less physical pleasures from hookups than men do, so the enjoyment of a hookup is gendered in favor of men. Men are also more prone to initiate the hook up and interactions leading up to a hook up. The primary gendered issue with hookups in this situation is the double standard we see for women. After sexual encounters men are praised for their actions and ‘scoring’ and women are often criticized and labeled negatively by peers and society, but if women turn down advances they are also labeled as ‘prude’ or ‘bitch’ for saying no to advances.

Next, let’s examine how perceptions of sexual behavior are viewed by peers and in what ways this is gendered. Social stigmas that surround women’s sexuality in ways that are highly restrictive and contradictory. Women are encouraged to participate, but not too willingly, and there may be backlash if women choose to have hookups. If women do not respond positively to advances they are criticized, but also if they do then they are labeled as ‘easy’ or ‘slut’. In some more recent research there is less criticism than previously, but many times the stigma and social responses are the same and negative no matter what the outcome of a hookup attempt. This culture is problematic because it socializes boys and men to strongly pursue sexual activity and to be aggressive in ‘achieving’ hookups.

10.3.6 Online Dating and the intersection of Gender, Race, and Sexuality

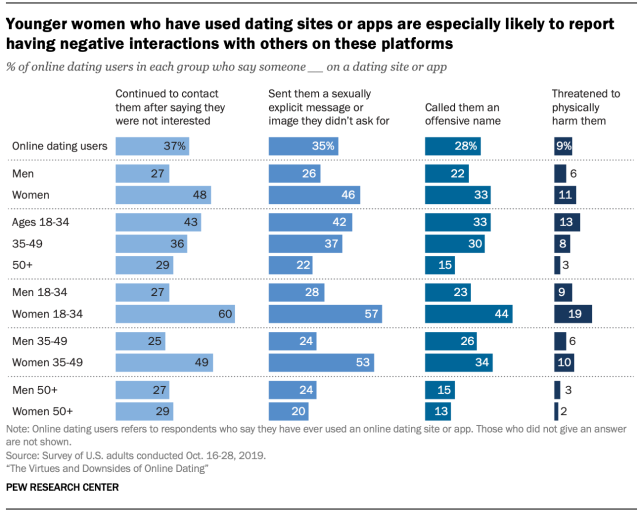

Today online dating is seen as normal and accessible for many. Currently over 30 percent of U.S. adults report using online dating sites or apps with overall mostly positive experiences (Pew Research Center 2020). How does the erotic marketplace (online dating and hookups) intersect with gender, race, and sexuality though? One way that we see dating and online dating be affected by gender is through the prevalence of sexual harassment and fear of assault when meeting people online in person. There are gender differences in the experience of online dating where women are more often the recipient of sexually explicit photos and unwanted contact (Figure 10.11).. When this is now the norm there is no reason to not be overly cautious about meeting in person. Men do receive unwanted sexually explicit photos or conversations, but the social norms are gendered and reflect a power dynamic where unwanted contact for women may lead to fear and concerns for safety. Women are twice as likely to say that they are concerned about their physical and emotional risks in dating.

Figure 10.11. Gender differences and the downside of online dating. Data from the Pew Research Center suggests that younger women report higher incidences of being harassed or sent sexually explicit messages.

An important piece to consider when studying online dating is the intersection of race with gender and sexuality. Historically women of color have been oversexualized and eroticized (think of characters like Esmerelda from Hunchback of Notre Dame), which translates into the online platforms in multiple ways. One way we see this intersectionality is simple bias/racism where comments like ‘I’m just not into -insert racial identity.’ Keep in mind that we don’t hear ‘I’m just not into white people’ as a common theme. This attitude stems from internalized racism and systemic ideals and stereotypes, such as idealized beauty standards for attractiveness. There is also clear transphobia in all dating, including online dating. The phrase ‘I won’t ever date a trans person’ is highly common, and yes, it is transphobic. If you decide not to date anyone because you do not find them attractive, your interests don’t match, you have different beliefs, it just doesn’t click then that’s normal. To clearly rule out someone that is trans is problematic. The idea of sexual identity in relation to trans people also comes up in online dating. Identity politics can become challenging for individuals. Imagine you identify as a lesbian and date someone who is openly a transman (someone who was biologically born a female, but whose gender identity is that of a man). There are concerns that this relationship could call your sexuality into question. Similarly, if you are a cis woman and date a transman, how do you view your relationship? How do others view your relationship?

Online dating has exploded over the last few years. Remember OkCupid? Yeah, that was a long time ago and then came Tinder which was more of a hookup app than a dating app when it first hit the online marketplace. Now we see dozens of apps for all sorts of things, including sexuality, sexual fetish, lifestyle, etc. OkCupid is still there, but we see there are apps for queer women, gay men, trans people, black people, religiously affiliated, kink, and on and on. We also have seen apps like Bumble that aim to put the ‘power’ in the hands of women as they control who can and can’t message them. Apps like Her, Lex, and Grindr are specifically made for lesbian, gay, trans, non-binary, and queer people, which tries to create a safe and accepting space that may not be available in other apps like Tinder, Bumble, Match, Hinge, etc. There are many narratives from people who are LGBTQIA+ about the lack of acceptance and also experiences harassment and hate on the more ‘traditional’ dating sites, so the intersections there are troubled and can cause a lack of participation in the dating arena. Also for LGBTQIA+ people, the percentage of couples who have met online are higher than for other sexuality groups. Some evidence suggests that this is due to safety, as well as knowing that the other person would be attracted to you. Without the apps, given our cultural adherence to heteronormativity, it might not be clear if someone is interested in someone sexually. Making assumptions about someone’s sexual identity can be dangerous if that person feels that the assumption is threatening their desired presentation of self.

10.3.7 Activity: Intersection Systems of Oppression

Figure 10.12. “Why Some Black LGBTQIA+ Folks Are Done ‘Coming Out’ [YouTube].”

- Consider the dynamics and intersections of power and privilege.What impact does that have on your life related to your own sexuality? Or someone you know?

- How do you think these intersections impact sexual practices in the United States?

- If we were to take into account intersectionality and create supports and spaces for that, what would that look like?

- How would the above changes impact institutions in the United States like workplaces, schools, healthcare?

10.3.8 Licenses and Attributions for Learning the “Rules” of Sexuality

“Learning the Rules of Sexuality” by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sexual Scripts” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sexual Assault and Sexual Violence” first paragraph by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0, all other content in this section by Heidi Esbensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figures 10.8 Advertisements (c) Dolce & Gabbana are included under fair use.

Figure 10.9 Photos by Staff Sgt. BreeAnn Sachs used under public domain, RODNAE Productions Nataliya Vaitkevich Kogulanath Ayappan and SlutWalk DC 2013 [02] by Ben Schumin.

Figure 10.10 and Activity video Challenging normalization of sexual violence against women | Susana Pavlou | TEDxUniversityofNicosia used by YouTube standard license.

Figure 10.11. “Younger women who have used dating sites or apps are especially likely to report having negative interactions with others on these platforms” from “The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating” (2020) © Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. is licensed under the Center’s Terms of Use.