11.6 Race and Group-Level Interactions

At this point, we’ve discussed theoretical perspectives on race and how race is experienced by the individual. Another key aspect of the experience of race happens at the level of group interactions. Intergroup relations (relationships between different groups of people) range along a spectrum between tolerance and intolerance. The most tolerant form of intergroup relations is pluralism, in which no distinction is made between minority and majority groups, but instead there’s equal standing. At the other end of the continuum are amalgamation, expulsion, and even genocide—stark examples of intolerant intergroup relations. We’ll discuss each of these in turn.

11.6.1 Pluralism

Pluralism is represented by the ideal of the United States as a “salad bowl”: a great mixture of different cultures where each culture retains its own identity and yet adds to the flavor of the whole. True pluralism is characterized by mutual respect on the part of all cultures, both dominant and subordinate, creating a multicultural environment of acceptance. In reality, true pluralism is a difficult goal to reach. In the United States, the mutual respect required by pluralism is often missing, and the nation’s past model of a melting pot posits a society where cultural differences aren’t embraced as much as erased.

11.6.2 Assimilation

Assimilation describes the process by which a minority individual or group gives up its own identity by taking on the characteristics of the dominant culture. In the United States, assimilation has been a function of immigration.

Most people in the United States have immigrant ancestors. In relatively recent history, between 1890 and 1920, the United States became home to around 24 million immigrants. In the decades since then, further waves of immigrants have come to these shores and have eventually been absorbed into U.S. culture, sometimes after facing extended periods of prejudice and discrimination. Assimilation may lead to the loss of the minority group’s cultural identity as they become absorbed into the dominant culture, but assimilation has minimal to no impact on the majority group’s cultural identity.

Some groups may keep only symbolic gestures of their original ethnicity. For instance, many Irish Americans may celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day, many Hindu Americans enjoy a Diwali festival, and many Mexican Americans may celebrate Cinco de Mayo. However, for the rest of the year, other aspects of their originating culture may be forgotten.

Assimilation is antithetical to the “salad bowl” created by pluralism; rather than maintaining their own cultural flavor, subordinate cultures give up their own traditions in order to conform to their new environment. When faced with racial and ethnic discrimination, it can be difficult for new immigrants to fully assimilate.

11.6.3 Amalgamation

Amalgamation is the process by which a minority group and a majority group combine to form a new group. Amalgamation creates the classic “melting pot” analogy; unlike the “salad bowl,” in which each culture retains its individuality, the “melting pot” ideal sees the combination of cultures that results in a new culture entirely.

Amalgamation is achieved through intermarriage between races. In the United States, antimiscegenation laws, which criminalized interracial marriage, flourished in the South during the Jim Crow era. It wasn’t until Loving v. Virginia (1967) that the last antimiscegenation law was struck from the books, making these laws unconstitutional.

The concept of the “melting pot” makes it seem like there is a blending of cultures, but in reality this notion was exclusively extended to white immigrants. In Race: Power of an Illusion, Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla Silva points out that people of color were not included in the melting pot. Instead, they were used as wood to produce fire for the pot.

11.6.4 Genocide

Genocide, the deliberate annihilation of a targeted (usually subordinate) group, is the most toxic intergroup relationship. Historically, we can see that genocide has included intentional and unintentional extermination of groups..

Possibly the most well-known case of genocide is Hitler’s attempt to exterminate the Jewish people in the first part of the twentieth century. Also known as the Holocaust, the explicit goal of Hitler’s “Final Solution” was the eradication of European Jewish people, as well as the destruction of other minority groups such as people with disabilities, and LGBTQIA+ people. With forced emigration, concentration camps, and mass executions in gas chambers, Hitler’s Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of 12 million people, 6 million of whom were Jewish. Hitler’s intent was clear, and the high Jewish death toll certainly indicates that Hitler and his regime committed genocide.

European colonizers committed genocide against Native Americans. Some historians estimate that Indigenous populations dwindled from approximately 12 million people in the year 1500 to barely 237,000 by the year 1900 (Lewy 2004). European settlers coerced American Indians off their own lands, often causing thousands of deaths in forced removals, such as occurred in the Cherokee or Potawatomi Trail of Tears. Settlers also enslaved Native Americans and forced them to give up their religious and cultural practices. But the major cause of Native American death was neither slavery nor war nor forced removal: it was the introduction of European diseases and Native American lack of immunity to them. Smallpox, diphtheria, and measles flourished among indigenous American tribes who had no exposure to the diseases and no ability to fight them. Quite simply, these diseases decimated the tribes. The use of diseases as a weapon was most likely unintentional in some cases and intentional in others. For example, during the Seven Years War, the British gave smallpox-infected blankets to the Native tribes in order to “reduce them,” and this and similar practices likely continued throughout the centuries-long assault on the Native American people.

Genocide is not a just a historical concept; it is practiced even in the twenty-first century. For example, ethnic and geographic conflicts in the Darfur region of Sudan have led to hundreds of thousands of deaths. As part of an ongoing land conflict, the Sudanese government and their state-sponsored Janjaweed militia have led a campaign of killing, forced displacement, and systematic rape of Darfuri people. Although a treaty was signed in 2011, the peace is fragile.

11.6.5 Expulsion

Expulsion refers to a subordinate group being forced, by a dominant group, to leave a certain area or country. As seen in the examples of the Trail of Tears and the Holocaust, expulsion can be a factor in genocide. However, it can also stand on its own as a destructive group interaction. Expulsion has often occurred historically with an ethnic or racial basis. In the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942, after the Japanese government’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The Order authorized the establishment of internment camps for anyone with as little as one-eighth Japanese ancestry (i.e., one great-grandparent who was Japanese). Over 120,000 legal Japanese residents and Japanese U.S. citizens, many of them children, were held in these camps for up to four years, despite the fact that there was never any evidence of collusion or espionage. In fact, many Japanese Americans continued to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by serving in the U.S. military during the War. In the 1990s, the U.S. executive branch issued a formal apology for this expulsion; reparation efforts continue today.

11.6.6 Segregation

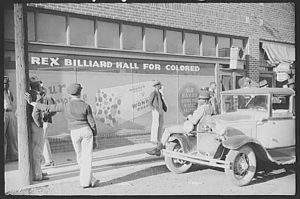

Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions. It is important to distinguish between de jure segregation (segregation that is enforced by law) and de facto segregation (segregation that occurs without laws but because of other factors). A stark example of de jure segregation is the apartheid movement of South Africa, which existed from 1948 to 1994. Under apartheid, black South Africans were stripped of their civil rights and forcibly relocated to areas that segregated them physically from their white compatriots. Only after decades of degradation, violent uprisings, and international advocacy was apartheid finally abolished.

De jure segregation occurred in the United States for many years after the Civil War. During this time, many former Confederate states passed Jim Crow laws that required segregated facilities for black and white people. These laws were codified in 1896’s landmark Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which stated that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional. For the next five decades, black people were subjected to legalized discrimination, forced to live, work, and go to school in separate—but unequal—facilities (figure 11.5). It wasn’t until 1954 and the Brown v. Board of Education case that the Supreme Court declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” thus ending de jure segregation in the United States.

De facto segregation, however, cannot be abolished by any court mandate. Few institutions desegregated as a result of Brown; in fact, government and even military intervention was necessary to enforce the ruling, and it took the Civil Rights Act and other laws to formalize the equality. Segregation is still alive and well in the United States, with different racial or ethnic groups often segregated by neighborhood, borough, or parish. Sociologists use segregation indices to measure racial segregation of different races in different areas. The indices employ a scale from zero to 100, where zero is the most integrated and 100 is the least. In the New York metropolitan area, for instance, the black-white segregation index was 79 for the years 2005–2009. This means that 79 percent of either black or white people would have to move in order for each neighborhood to have the same racial balance as the whole metro region (Population Studies Center 2010).

The next section, “Pedagogical Element: Race and Interactions” you will learn more about intergroup relations. First you’ll have the opportunity to review theories of prejudice and types of interactions covered in this section before thinking about how race structures our major social institutions.

11.6.7 Activity: Race and Interactions

Please watch this 11-minute clip Racial/Ethnic Prejudice & Discrimination: Crash Course Sociology #35 [YouTube Video] which will review concepts of prejudice and discrimination before making connections to racial groups and patterns of interaction. After watching the video, please return and answer the following questions:

- Why does prejudice continue to exist?

- What are some examples of institutional racism?

- Reflect on the patterns of interaction discussed in the video and your chapter. Find news stories related to a couple of the patterns and share them with your classmates.

Figure 11.6. Racial/Ethnic Prejudice & Discrimination: Crash Course Sociology #35 [YouTube Video]

11.6.8 Licenses and Attributions for Race and Group-Level Interactions

“Race and Group Level Interactions” from “11.4 Intergroup Relationships” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/11-4-intergroup-relationships; edited for consistency, clarity, and brevity.

“Pedagogical Element: Race and Interactions” and figure 11.6 screenshot adapted from Racial/Ethnic Prejudice & Discrimination: Crash Course Sociology #35 by Crash Course Sociology. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.