2.3 Creating a Discipline: European Theorists

The origins of sociology are typically traced back to a variety of European thinkers that lived primarily in the 1800s into the early 1900s. Often these theorists sought to explain the large social changes that were occurring in their societies at the time. Some of the theorists wrote extensively about very different aspects of society. To help maintain some coherency we will focus on what the theorists said about the economy and religion when appropriate. Yet, as noted earlier, there were some topics these theorists did not address such as issues related to gender, race, and colonialism.

2.3.1 Positivism and Social Science: Auguste Comte (France, 1798-1857)

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) in an unpublished manuscript. In 1838, the term was reintroduced by Auguste Comte (figure 2.5). Comte was a pupil of social philosopher Claude Henri de Rouvroy Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825). They both thought that social scientists could study society using the same scientific methods utilized in the natural sciences. Comte developed a theory of positivism, which means that science produces universal laws, science controls what is true, and that objective methods allow you to pursue that truth. Comte viewed sociology as the study of two important forces: stability, which he called statics, and change, which he called dynamics. Statics are the laws or structures that contribute to the stability of society. The dynamics are aspects of the society that are changing.

2.3.2 Capitalism and Morals: Harriet Martineau (England, 1802–1876)

Harriet Martineau introduced sociology to English speaking scholars through her translation of Comte’s writing from French to English (figure 2.6). She was an early analyst of social practices, including economics, social class, religion, government, and women’s rights. Her career began with Illustrations of Political Economy, a work educating ordinary people about the principles of economics (Johnson 2003). She later developed the first systematic methodological international comparisons of social institutions in two of her most famous sociological works: Society in America (1837) and Retrospect of Western Travel (1838).

Martineau found the workings of capitalism at odds with the professed moral principles of people in the United States. She pointed out the faults with the free enterprise system in which workers were exploited and impoverished while business owners became wealthy. She further noted that the belief that all are created equal was inconsistent with the lack of women’s rights. Martineau was often discounted in her own time because academic sociology was a male-dominated profession. In the 1970s feminist scholars rediscovered her work. What would the foundations of sociology look like today if her work had been included earlier on?

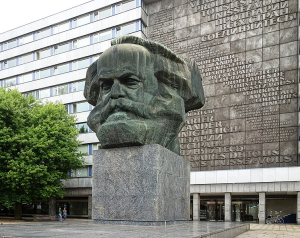

2.3.3 Class and Conflict: Karl Marx (Germany, 1818–1883)

Karl Marx was a social critic and philosopher from Germany (figure 2.7). Exiled from his homeland due to his political beliefs and publications, he ultimately settled in London. He, along with Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), wrote an influential pamphlet called The Communist Manifesto (1848). In the manifesto they outline their approach to history and class struggle, while arguing for communism. In Das Kapital, Marx developed an analysis of how capitalism works. His ideas proved very influential for critical social theories within sociology. To this day some sociologists continue to draw inspiration from his writings.

Marx argued that history could be divided up into a series of distinctive time periods or epochs based on the social relations and technologies available at the time. The main driver between epochs was class struggle (masters versus slaves, landlords versus serfs, owners versus workers). In each epoch a revolutionary class would emerge and overthrow those in control, which would instigate the next epoch.

In capitalists societies, Marx identified two distinct social classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie were the wealthy owners/capitalists, who control economic production. The proletariat were the workers, they must sell their labor to live and make a wage. The relationship between the two classes are inherently antagonistic. The bourgeoisie want to make as much profit possible, while paying the proletariat as low as possible. The proletariat want to get paid higher wages. Marx argued that the owners exploited the workers by paying them less than what their labor is worth and what they sell the products for.

Marx argued that workers become alienated from their work. He noted that people can be alienated from their work in four different ways. People are alienated from the objects they produce, from the process of work itself, from one’s sense of self (“species-being”) and from other workers.

Thinking more broadly about the structures of societies, Marx argued that society could be divided into an (economic) base and (cultural) superstructure. The economic base includes economic relations and technology. The superstructure includes all the institutions of a society outside of the economy, including religion, education, family, media, politics and more generally culture. Marx argued the base determined and shaped the superstructure. The superstructure then reinforces what is happening in the base by promoting a specific set of ideas and values. To Marx whichever class controls the economic base controls larger superstructure and the dominant ideas of the society. In capitalist societies that would be the bourgeoisie.

Ultimately all of this leads to the rich getting richer, and the poor getting poorer. Workers getting stuck because there is a reserve army of other workers who are willing to jump in for lower pay if the workers decide to unionize or challenge the owners. Given the exploitation experienced by the workers, Marx argued they would eventually decide to rise up and overthrow capitalism and the owners. This would result “In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic” (1845). How might we envision other utopias?

2.3.4 Science and Religion: Émile Durkheim (France, 1858–1917)

Émile Durkheim was a crucial voice in the promotion of sociology as a legitimate area of study within France (figure 2.8). In his writing he argued that sociology was a science and he provided a set of rules for conducting social scientific research in Rules of the Sociological Method (Adams and Sydie 2001). He wrote on variety of topics, here we will explore his work on the economy, suicide, and religion.

Émile Durkheim was interested in how societies cohere and how people connect to each other. In The Division of Labor he explores how social cohesion changed during a time of rapid economic and social transition (from a feudal to industrial based economy). Durkheim argued that people in pre-industrial societies related to each other based on common sentiments and moral values. This was possible because of mechanical solidarity, meaning a minimal division of labor and limited individuality. This type of solidarity is based on people feeling similar to each other. In such societies, groups take precedence over the individual. In terms of work, there is not much specialization and people complete a wide variety of tasks.

In contrast, with organic solidarity people relate to each other based on specialization and interdependence. Individuality and difference are maximized. He argued that organic solidarity characterized modern industrial societies. With the increased division of labor and specialization of work we depend more and more on people that we do not know personally.

In 1897, Durkheim attempted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his rules of social research when he published a work titled Suicide. Durkheim examined suicide statistics in different police districts to research differences between Catholic and Protestant communities. He attributed the differences to socio-religious forces rather than to individual or psychological causes.

One of his final studies, the Elementary Forms of Religious Life (2001[1915]) explores the social underpinnings of religion. He defined religion as a unified system of beliefs and practices related to sacred things or things that are set apart and forbidden. He argued that the common denominator of all religions are their beliefs that divided the world into the sacred and the profane, along with prescriptions of particular ways of behaving toward the sacred.

So what did he mean by the sacred and the profane? The sacred involves feelings of awe, fear, and reverence. Animals, places, plants, or people can be designated sacred. It is something added to the object or thing by the group. The profane is the opposite of the sacred. This is routine daily life. Such as work and household chores. Instead of providing a way for society to worship itself and causing people to form social bonds, Durkheim saw the profane as weakening shared commitments to beliefs and social bonds.

How does society sustain itself in face of the profane? Durkheim argued that rituals played a large role in helping people reaffirm their worship of shared objects, having shared experiences and sustaining emotional bonds. Rituals are when society would come together to worship the sacred and reaffirm people’s connections with one another. Through such things as music, chants, dance, rituals create a collective emotional excitement-called collective effervescence. This provides a strong sense of group belonging, with people losing their sense of self in the collective experience. This collective energy sustains people in the face of the profane.

Overall, this led Durkheim to view the existence of religion resulting from societies needing to reconstruct their social bonds in face of the routine and everyday that leads to feelings of disconnection. The other conclusion Durkheim came to about religion was that it was nothing less than the worship of society itself.

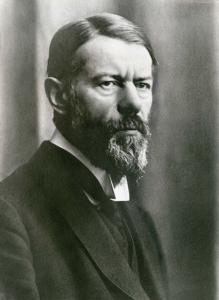

2.3.5 The Protestant Ethic and Rationality: Max Weber (Germany, 1864–1920)

Max Weber was a well known German intellectual, whose work spanned multiple disciplines (figure 2.9). A prolific scholar, he was also politically active in pre-World War I Germany. Within sociology his writings on the development of capitalism, the economy, social action, and research methods continue to be influential. Weber was interested in how capitalism emerged and where it was going. Unlike Marx who based his theories on class struggle and economic relations, Weber focused on the role ideas played in the spread of capitalism.

Weber began by observing that Protestants were overrepresented in capitalist economic activity and asked why. He argued in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (2002[1904-1905]), Protestants had a “Protestant Ethic.” This ethic involved the systematic pursuit of salvation in the everyday world. According to German priest and religious reformer Martin Luther, to live acceptable to God was to live in the world and fulfill one’s duties. This contrasted to the idea that the most virtuous existence was a monastic one where one renounce worldly obligations and wealth.

One way to serve God was to pursue one’s vocation, which became known as a “calling.” This meant, each person had a specific place and job in God’s scheme and the pursuit of one’s vocation was a way of serving God. Hard work in one’s calling would normally bring about material rewards to the believer. These rewards would provide psychological comfort that one was headed towards heaven because Protestants assumed that God would not reward those who were damned. The wealth the people accumulated from their hard work in their calling became acceptable.

The Protestant Ethic resulted in people who worked hard but didn’t spend or enjoy their profits. This pattern of behavior aligned with Weber called the “spirit of capitalism.” He called the spirit of capitalism the overall guiding principles of capitalism. These principles included acquisition, which the Protestant Ethic encouraged with hard work and as evidence of salvation. Reinvestment was another principle of capitalism. Reinvestment entails a commitment to continuously use profits to increase capital instead of using the profits for consumption, which religious doctrine frowned upon. The beliefs associated with the Protestant Ethic helped capitalism emerge and make it morally acceptable.

By the 20th century capitalism no longer needed the direct support of religious beliefs. Once it came into power secular capitalism had a self sustaining, treadmill like character. What was left was an instrumental rationality, a way of thinking that focused on short term goals and acting in a self interested manner. To some extent, with this way of thinking people approach social life asking “what is in it for me?” With the increase in instrumental rationality and the declining influence of moral beliefs and values over capitalism, Weber saw capitalism headed toward an “iron cage,” where the world is disenchanted. There is a loss of values and meaning, coupled with a rise in cold calculations and efficiency.

Weber also believed that it was difficult, if not impossible, to use standard scientific methods to accurately predict the behavior of groups as some sociologists hoped to do. Weber argued that the influence of culture on human behavior had to be taken into account. This even applied to the researchers themselves, who should be aware of how their own cultural biases could influence their research. To deal with this problem, Weber and German academic Wilhelm Dilthey introduced the concept of verstehen, a German word that means to understand in a deep way. In seeking verstehen, outside observers of a social world—an entire culture or a small setting—attempt to understand it from an insider’s point of view.

2.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Creating a Discipline

“Positivism and Social Science ” is modified from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax; https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-2-the-history-of-sociology. Added detail about positivism, statics and dynamics.

“Capitalism and Morals” is from “1.2 The History of Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax; https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-2-the-history-of-sociology. Added last two sentences on rediscovery of her work.

Paragraph on Durkheim’s study of suicide in “Science and Religion” is from “1.2 The History of Sociology”by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax; https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-2-the-history-of-sociology.

Paragraph on verstehen in “The Protestant Ethic and Rationality” is from “1.2 The History of Sociology”by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at OpenStax; https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-2-the-history-of-sociology.

All other content in this section is original content by Matthew Gougherty and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figures

Figure 2.5. The bust, part of the monument to Auguste Comte, by Jean-Antoine Injalbert, 1902. Place de la Sorbonne, Paris. By Jebulon. License: CC0 1.0

Figure 2.6 Portrait of Harriet Martineau by Richard Evans. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2.7. Karl Marx Monument in Chemnitz by Velvet. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 2.8. Photos d’un buste d’Émile Durkheim by Chirstian Baudelot. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 2.9. Max Weber, 1918. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.