3.2 Approaches to Sociological Research

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a question about a new trend or a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

3.2.1 Developing a Research Question and the Steps of the Scientific Method

As sociology made its way into American universities, scholars developed it into a science that relies on research to build a body of knowledge. Sociologists began collecting data (observations and documentation) and applying the scientific method or an interpretative framework to increase understanding of societies and social interactions.

Our observations about social situations often incorporate biases based on our own views and limited data. To avoid subjectivity, sociologists conduct systematic research to collect and analyze empirical evidence from direct experience. Peers review the conclusions from this research. Examples of peer-reviewed research are found in scholarly journals.

Sociologists use a variety of methods for research, such as surveys, ethnographies (field research), and interviews. Humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. However, scientific models and the scientific process of research can be applied to the study of human behavior. A scientific approach to research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

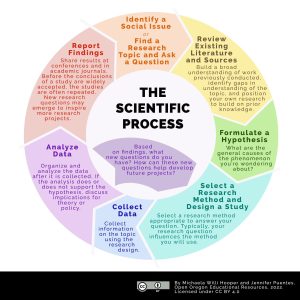

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. The scientific method follows deductive reasoning, rather than the inductive approach we see with grounded theory. It involves a series of seven steps as shown in figure 3.2. Not every research project follows the steps in order, but this approach provides a plan for conducting research systematically.

Figure 3.2 outlines key stages in the research process. Please note that these stages or steps can be experienced as an ongoing process. Researchers and students undertaking projects may need to repeat steps as they go through the research process.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of community cohesiveness, employment, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, neighborhood organizations, and higher education patterns.

Good research questions address sociological issues, connect to prior sociological research studies, are narrow enough that one study could help answer it, and can be examined through data (readily available or able to be collected given your time and resources) (Smith-Lovin and Moskovitz 2017:57). The process of designing research questions involves an emphasis on first reviewing the previous literature to identify connections the researcher should explore in their study (Loske 2017). This is something you will want to keep in mind; it is not uncommon for research questions to change overtime as you continue to incorporate new literature.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure consistency in exploring a social phenomena.

Step 1: Identify a Social Issue/Find a Research Topic and Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to be of significance. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variable (IV), which is the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV), which is the effect, or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

With a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)? The table in Figure 3.3 demonstrates the relationship between a hypothesis, independent variable, and dependent variable.

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the homeless rate. | Affordable Housing | Homeless Rate |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. | Math Tutoring | Math Grades |

| The greater the police patrol presence, the safer the neighborhood. | Police Patrol Presence | Safer Neighborhood |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. | Factory Lighting | Productivity |

| The greater the amount of media coverage, the higher the public awareness. | Observation | Public Awareness |

Figure 3.3. Examples of Dependent and Independent Variables. Typically, the independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way.

Taking an example from figure 3.3, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two related topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Select a Research Method and Design a Study

Researchers select a research method that is appropriate to answer their research question in this step. Surveys, experiments, interviews, ethnography, and content analysis are just a few examples that researchers may use. You will learn more about these and other research methods later in this chapter in the section “Social Science Research Methods.” Typically your research question influences the type of methods that will be used.

Step 5: Collect Data

Next the researcher collects data. Depending on the research design (step 4), the researcher will begin the process of collecting information on their research topic. After all the data is gathered, the researcher will be able to systematically organize and analyze the data.

Step 6: Analyze the Data

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss what this might mean. For example, there could be implications for public policy or existing theories. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, that can be an important finding to report. Some researchers may consider repeating the study or think of ways to improve their procedure (this step is more commonly seen with experiments).

Even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, the results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, for example, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Step 7: Report Findings

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develop as the relationships between social phenomena are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

3.2.2 Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on empirical data and the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework. Interpretive framework is an approach that involves detailed understanding of a particular subject through observation, not through hypothesis testing. Interpretive frameworks allow researchers to have reflexivity so they can describe how their own social position influences what they research. By reflexivity, we refer to the ability of the researcher to examine how their own social position influences how and what they research. Reflexivity requires the researcher to evaluate how their own feelings, reactions and motives influence how they think and behave in a situation.

While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective or approach, seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge or understanding about the human experience. Ethnography is one research method that uses an interpretive framework. You will learn more about this method in the next section.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects including storytelling. This type of researcher learns through the process and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

3.2.3 Grounded Theory

Grounded theory uses an interpretive framework to make sense of the social world. Grounded theory is an approach developed by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (1967) at a time when researchers were questioning positivism. As you learned in Chapter 2, positivism refers to Auguste Comte’s theory that science produces universal laws, science controls what is true, and that objective methods allow you to pursue that truth. A counter perspective, anti-positivism, offers a different theoretical perspective that suggests social life cannot be studied with the same methods used in natural sciences. Instead there is a push to use a different approach.

Grounded theory offers a different approach to analysis that is sometimes used in qualitative research and aims to help with the development of theory (Charmaz 2003). This systematic theory is “grounded in” or based on observations. It uses induction or inductive reasoning, which means you use specific observations or evidence to arrive at broad conclusions. With grounded theory the research starts by gathering observations before creating categories to organize the data in. After initially organizing the data into categories, they begin to look for patterns and relationships among categories (Glaser and Strauss 1967). A few methods that may commonly utilize a grounded theory approach are participant observation, interviewing, and secondary data collection of artifacts and texts.

3.2.4 Critical Sociology

Critical sociology focuses on deconstruction of existing sociological research and theory. This approach to methods is nformed by the work of Karl Marx, and feminist, postmodern, postcolonial, and critical race scholars. These critical sociologists propose that social science is embedded in systems of power. Power is constituted by the set of class, caste, race, gender, and other relationships that exist in the society. We will take a closer look at these power relations in later chapters. Consequently, power cannot be treated as purely objective. Critical sociologists view theories, methods, and the conclusions as serving one of two purposes: they can either legitimize and rationalize systems of social power and oppression or liberate humans from inequality and restriction on human freedom. We’ll explore examples of this approach in the section, “Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Indigenous Knowledge and Decolonizing Research Methods” section later in this chapter.

3.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Approaches to Sociological Research

“Approaches to Sociological Research” from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

“Developing a Research Question & the Steps of the Scientific Method” – First two paragraphs from “Introduction” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-introduction

Paragraphs 3 and 4 edited for consistency and brevity, Figure 3.3 and Step sections edited and modified from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

Figure 3.2. “Interpretive Framework” modified from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

Interpretive framework definition modified from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Reflexivity definition modified from the Cambridge Dictionary is licensed under X

“Grounded Theory” is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Anti–positivism definition is adapted from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and from Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

“Critical Theory” remixed from “2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for clarity. Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Image Description for Figure 3.2:

A circle of arrows around the words Scientific Process. The top arrow says Identify a Social Issue or Find a Research Topic and Ask a Question. This points to the next arrow, which says review existing literature and sources. Build a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position your own research to build on prior knowledge. The next arrow says Formulate a Hypothesis: What are the general causes of the phenomenon you’re wondering about? The next arrow says Select a Research Method and Design a Study: Select a research method appropriate to answer your question. Typically, your research question influences the method you will use. The next arrow says Collect data: Collect information on the topic using the research design. The next arrow says Analyze data: Organize and analyze the data after it is collected. If the analysis does or does not support the hypothesis, discuss implications for theory or policy. From here there is an arrow that goes back to Select a Research Method that says Based on findings, what new questions do you have? How can these new questions help develop future projects? Another arrow from Analyze Data continues the circle and says Report Findings: Share results at conferences and in academic journals. Before the conclusions of a study are widely accepted, the studies are often repeated. New research questions may emerge to inspire more research projects. This arrow points back to the top arrow where we started. There is also an attribution statement saying this image is CC BY 4.0 and created by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper.

[Return to Figure 3.2]