3.5 Ethics

Sociologists conduct studies to shed light on human behaviors. Knowledge is a powerful tool that can be used to achieve positive change. As a result, conducting a sociological study comes with a tremendous amount of responsibility. Like all researchers, sociologists must consider their ethical obligation to avoid harming human subjects or groups while conducting research.

Research studies that use human subjects often undergo review by a community at the researcher’s university called the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If projects are approved, researchers seek out participants. Research participants are thanked for their participation and sometimes offered a chance to see the results of the study if they are interested.

German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) identified another crucial ethical concern. Weber understood that personal values could distort the framework for disclosing study results. While he accepted that some aspects of research design might be influenced by personal values, he declared it was entirely inappropriate to allow personal values to shape the interpretation of the responses. Sociologists, he stated, must establish value neutrality, a practice of remaining impartial, without bias or judgment, during the course of a study and in publishing results (Weber, 1949). Sociologists are obligated to disclose research findings without omitting or distorting significant data.

Is value neutrality possible? Many sociologists believe it is impossible to retain complete objectivity. They caution readers, rather, to understand that sociological studies may contain a certain amount of value bias. This does not discredit the results, but allows readers to view them as one form of truth—one fact-based perspective. Investigators are ethically obligated to report results, even when they contradict personal views, predicted outcomes, or widely accepted beliefs.

3.5.1 ASA Code of Ethics

The American Sociological Association, or ASA, is the major professional organization of sociologists in North America. The ASA is a great resource for students of sociology as well. The ASA maintains a code of ethics—formal guidelines for conducting sociological research—consisting of principles and ethical standards to be used in the discipline. These formal guidelines were established by practitioners in 1905 at John Hopkins University, and revised in 2018. When working with human subjects, these codes of ethics require researchers’ to do the following:

- Professional Competence: Sociologists should maintain a high level of competence and recognize the limitations of their expertise. Sociologists should participate in ongoing education to remain professionally competent and consult with other professionals when necessary.

- Integrity: Sociologists should be honest, fair, and respectful to others. Sociologists do not intentionally engage in practices that harm the welfare of themselves or others.

- Professional and Scientific Responsibility: Sociologists maintain high scientific and professional standards. They accept responsibility for their work and show respect for other sociologists when they disagree on theoretical and methodological approaches.

- Social Responsibility: Sociologists respect people’s rights, dignity, and diversity. They are aware of cultural, individual, and role differences in serving, teaching, and studying groups of people with different characteristics.

- Human Rights: Sociologists are committed to promoting the human rights of all people through their research, teaching, practice, and service.

3.5.2 Unethical Studies

Unfortunately, when these codes of ethics are ignored, it creates an unethical environment for humans being involved in a sociological study. Throughout history, there have been numerous unethical studies, some of which are summarized below.

3.5.2.1 The Tuskegee Experiment

This study was conducted 1932 in Macon County, Alabama, and included 600 African American men, including 399 diagnosed with syphilis. The participants were told they were diagnosed with a disease of “bad blood.” Penicillin was distributed in the 1940s as the cure for the disease, but unfortunately, the African American men were not given the treatment because the objective of the study was to see “how untreated syphilis would affect the African American male” (Caplan, 2007)

3.5.2.2 Henrietta Lacks

Ironically, this study was conducted at the hospital associated with Johns Hopkins University, where codes of ethics originated. In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was receiving treatment for cervical cancer at John Hopkins Hospital, and doctors discovered that she had “immortal” cells, which could reproduce rapidly and indefinitely, making them extremely valuable for medical research (figure 3.9). Without her consent, doctors collected and shared her cells to produce extensive cell lines. Lacks’ cells were widely used for experiments and treatments, including the polio vaccine, and were put into mass production. Today, these cells are known worldwide as HeLa cells (Shah, 2010).

3.5.2.3 Milgram Experiment

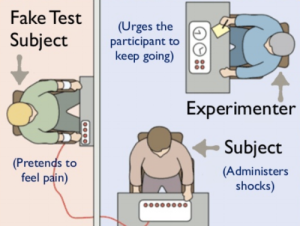

In 1961, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment at Yale University. Its purpose was to measure the willingness of study subjects to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience. Figure 3.10 is a diagram of his study. People in the role of teacher believed they were administering electric shocks to students who gave incorrect answers to word-pair questions. No matter how concerned they were about administering the progressively more intense shocks, the teachers were told to keep going. The ethical concerns involve the extreme emotional distress faced by the teachers, who believed they were hurting other people (Vogel 2014).

3.5.2.4 Philip Zimbardo and the Stanford prison experiment

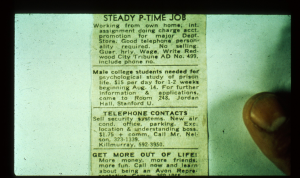

In 1971, psychologist Phillip Zimbardo conducted a study involving students from Stanford University. The students were put in the roles of prisoners and guards, and were required to play their assigned role accordingly. The experiment was intended to last two weeks, but it only lasted six days due to the negative outcome and treatment of the “prisoners.” Beyond the ethical concerns, the study’s validity has been questioned after participants revealed they had been coached to behave in specific ways.

3.5.2.5 Laud Humphreys

In the 1960s, Laud Humphreys conducted an experiment at a restroom in a park known for same-sex sexual encounters. His objective was to understand the diversity of backgrounds and motivations of people seeking same-sex relationships. His ethics were questioned because he misrepresented his identity and intent while observing and questioning the men he interviewed (Nardi 1995).

3.5.2.6 Ethics in International Research

Ethics in International Research begins with the same ethical considerations of research in the researcher’s home environment. However, additional considerations are made considering the cross cultural nature of the work, and to navigate unequal power imbalances between researchers and the communities they are studying.

In international settings there may exist different cultural approaches and understandings about ethics in research in general, so it is helpful for researchers to establish relationships with local organizations to better understand those cultural differences. Members of local organizations can advise on any cultural, moral and political sensitivities that might influence any risks to safety and dignity with participants.

Especially with international research in low-income countries, or countries in conflict or political instability, researchers are encouraged to play close attention to power imbalances between themselves and local communities. These power imbalances may be real or perceived, and may impact the degree to which community members feel their participation is voluntary, how freely they grant specific consent for participation, and participants’ expectations of what the research will contribute, if anything, to the community. Special attention needs to be provided to bridge cultural and language gaps to make certain that participants understand the details of the informed consent, at times, providing translated or orally-presented information (International Research n.d).

3.5.3 Activity: A Closer Look at Research Ethics

Let’s look at how one organization outlines ethics for international research. The Australian Council for International Development (ACID) works to strengthen organizations’ impact against poverty, so their focus on international research has a humanitarian, or development lens. Watch their 3:35-minute video, Principles and Guidelines for Ethical Research and Evaluation in Development [YouTube Video] (figure 3.13). As you do, keep track of the principles that ACID encourages.

Figure 3.13. Principles and Guidelines for Ethical Research and Evaluation in Development [YouTube Video]

Discussion Question: How do ACID’s principles for ethical research compare to the principles we covered in this section?

3.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Ethics

“Ethics” modified from “2.3 Ethical Concerns” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency, brevity, and to update information. Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-3-ethical-concerns

“Ethics” paragraph 2 is original content by Jennifer Puentes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Ethics in International Research” is original content by Aimee Krouskop and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Pedagogical Element: A Closer Look at Research Ethics” and figure 3.13 screenshot adapted from Principles and Guidelines for Ethical Research and Evaluation in Development (c) ACFID. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.13. Screenshot from Principles and Guidelines for Ethical Research and Evaluation in Development (c) ACFID. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

Images

Figure 3.8. Photo. (c) Centers for Disease Control. Used under fair use.

Figure 3.9. Photo. (c) History.com -Henrietta Lacks (photo credit: Lacks family). Used under fair use.

Figure 3.10. Diagram illustrating Milgram’s Obedience Study

Figure 3.11. Photo. (c) Philip Zimbardo https://www.prisonexp.org/gallery. Ad for Participants. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 3.12. Photo. (c) Philip Zimbardo https://www.prisonexp.org/gallery. Doing Pushups. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Image Description for Figure 3.10:

A diagram shows three people. Two are seated in the same room at desks with devices that have buttons. One is labeled as the experimenter, who is writing on a piece of paper. This person convinces a participant, called a teacher, to administer what they think are shocks to someone in the room next door, called a learner. A wire runs from the teacher’s desk to the learner’s desk in the next room. The teacher believes they are giving painful shocks to the learner, but the learners are actors who only pretend to be in pain.

[Return to Figure 3.10]