8.4 Social Classes in the United States

In this section we will explore how class operates in the United States. We will begin by exploring those high up in the class hierarchy and then discuss the middle class. We will end by examining poverty in the United States, how it is patterned, and explanations for its persistence.

8.4.1 Upper Class

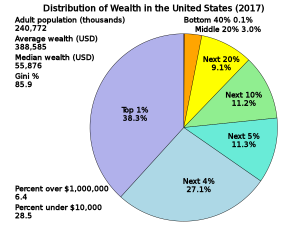

The upper class is considered the top, and only the powerful elite get to see the view from there. In the United States, people with extreme wealth make up one percent of the population, and they own roughly one-third of the country’s wealth (figure 8.3) (Beeghley 2008).

Money provides not just access to material goods, but also access to power. As corporate leaders, members of the upper class make decisions that affect the job status of millions of people. As media owners, they influence the collective identity of the nation. They run the major network television stations, radio broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, publishing houses, and sports franchises. As board members of the most influential colleges and universities, they influence cultural attitudes and values. As philanthropists, they establish foundations to support social causes they believe in. As campaign contributors and legislation drivers, they fund political campaigns to sway policymakers, sometimes to protect their own economic interests and at other times to support or promote a cause.

Sociologists have explored the composition and dynamics of the American elites. American sociologist C. Wright Mills coined them the “power elite” (2000) The power elite is the class in command of the major hierarchies and organizations of modern society. Mills points to the government, corporations, and the military as the three main institutions in which the elite circulate. As an example, someone that held a high position in the government might go onto serve on the board of a corporation. Or someone that was a corporate executive (such as Michael Bloomberg, Mitt Romney, or Donald Trump) might then be elected into a high position in the government.

This interconnectedness of the power elite also takes place outside of formal institutions with overlapping networks and connected groups. Mills suggests that the power elite use a particular ideology to justify their location. The power elite promote the belief that they have a finer moral character and that there is something about them that makes them “naturally” elite. In doing so, they downplay the importance of shared experiences and training in reproducing elite statuses. Further, the power elites in the United States tend to deny that they are powerful.

American sociologist G. William Domhoff also studied elites in the United States. He found that elites developed their own social institutions to help create social cohesion and to help mold wealthy people into an actual upper class (Domhoff 2021). This social cohesion develops from common membership in specific institutions and friendships based on social interaction within the institutions.

Domhoff focuses on education and social clubs as areas where the upper class builds their cohesion and is able to reproduce itself. In terms of education, children of the upper class receive a distinctive education that socializes them into their privileged class position. This education starts in preschool and elementary school with the kids of the upper class going to local private schools. As the children of the upper class get older, there is a strong chance that they will spend a few years away at a boarding school in a rural setting (Cookson and Persell 1985; Khan 2011). In terms of higher education, those from the upper class generally go to a small number of private colleges and universities (Karabel 2006; Stevens 2011) .

Private social clubs are another institution that plays an important role in the lives of upper-class adults. These clubs are formed around a variety of activities, with many families having memberships in several types of clubs in different cities (Domhoff 2021).

8.4.2 Middle Class

Many people consider themselves middle class, but there are differing ideas about what that means. People with annual incomes of $150,000 call themselves middle class, as do people who annually earn $30,000. That helps explain why, in the United States, the middle class is broken into upper and lower subcategories.

Lower-middle-class members tend to complete a two-year associate’s degree from community or technical colleges or a four-year bachelor’s degree. Upper-middle-class people tend to continue on to postgraduate degrees. They’ve studied subjects such as business, management, law, or medicine.

Middle-class people work hard and live fairly comfortable lives (figure 8.4). Upper-middle-class people tend to pursue careers, own their homes, and travel on vacation. Their children receive high-quality education and healthcare (Gilbert 2010). Parents can support more specialized needs and interests of their children, such as more extensive tutoring, arts lessons, and athletic efforts, which can lead to more social mobility for the next generation. Families within the middle class may have access to some wealth, but also must work for an income to maintain this lifestyle.

In the lower-middle class, people hold jobs supervised by members of the upper-middle class. They fill technical, lower-level management or administrative support positions. Compared to lower-class work, lower-middle-class jobs carry more prestige and come with slightly higher paychecks. With these incomes, people can afford a decent, mainstream lifestyle, but they struggle to maintain it. They generally don’t have enough income to build significant savings. In addition, their class standing is more precarious than those in the upper tiers of the class system. When companies need to save money, lower-middle-class people are often the ones to lose their jobs.

Sociologists have conducted a variety of studies on the middle class. In one influential study, sociologist Michèle Lamont (1992) explored the symbolic boundaries that middle-class men drew. The men used these boundaries to determine who was part of the middle class and who was not. Lamont found that the men drew boundaries on cultural, socioeconomic, and moral criteria. Focusing on the socioeconomic criteria, she identified different components to this boundary.

The middle-class men associated money with freedom, control, and security. Money provided a certain comfort level that became a symbol and reward of professional success. It also provided cars, homes, and vacations.

The middle-class men also valued membership in prestigious groups and associations. Belonging to such groups and associations provides information on socioeconomic status. This signals the fact that they’ve achieved a certain income level and that they’ve been accepted by the right kinds of people. This involves belonging to churches, the chamber of commerce, political parties, and alumni associations, all of which provide additional opportunities to meet middle-class people and build connections with them.

The middle class tends to raise their children in a particular way. They engage in what sociologist Annette Lareau calls concerted cultivation. Concerted cultivation is when parents “deliberately try to stimulate their children’s development and foster their cognitive and social skills” (Lareau 2003: 5). To accomplish this, middle-class parents encouraged their children to become involved in activities outside the home. This leads middle-class children to develop a set of skills and dispositions that help them navigate institutions that value such skills. As a result, the children start developing a sense of entitlement, the belief that they deserve these benefits.

8.4.3 The Lower Class

The lower class is also referred to as the working class. Just like the middle and upper classes, the lower class can be divided into subsets: the working class, the working poor, and the underclass. Compared to the lower-middle class, people from the lower economic class have less formal education and earn smaller incomes. They work jobs that require less training or experience than middle-class occupations and often do routine tasks under close supervision.

Working-class people, the highest subcategory of the lower class, often land steady jobs. The work is hands-on and often physically demanding, such as landscaping, cooking, cleaning, or building.

Michèle Lamont (2000) also conducted a study looking at the boundaries drawn by working-class men. She found unlike men from the middle class, working-class men placed a stronger emphasis on moral boundaries. By emphasizing morality it helped the workers maintain a sense of self-worth. The moral boundaries allowed them to affirm their dignity independently of their relatively low social status and to locate themselves above “others.” Particularly they drew a line between themselves and the more economically advantaged who they perceived as less morally pure.

Working-class families tend to engage in the accomplishment of natural growth. In this approach to child-rearing, families provide the basic necessities, which is an accomplishment given the harsh economic conditions they face. The parents assume that their children’s growth will occur naturally. As a result there is less emphasis placed on participating in after-school activities. Instead, the children engage in child-initiated play with friends and family (Lareau 2003).

While there are benefits to this approach to raising children, our institutions tend to favor middle-class child-rearing techniques. For example, schools tend to expect heavy parental involvement. For the working-class kids, this disconnect between their socialization and what institutions expect from them leads to a sense of constraint (Lareau 2003, Calarco 2018).

Beneath the working class is the working poor. They have unskilled, low-paying employment. However, their jobs rarely offer benefits such as healthcare or retirement planning, and their positions are often seasonal or temporary. They work as migrant farm workers, house cleaners, and day laborers. Education is limited. Some lack a high school diploma.

How can people work full-time and still be poor? Even working full-time, millions of the working poor earn incomes too meager to support a family. The government requires employers pay a minimum wage that varies from state to state and often leaves individuals and families below the poverty line. In addition to low wages, the value of the wage has not kept pace with inflation. “The real value of the federal minimum wage has dropped 17 percent since 2009 and 31 percent since 1968” (Cooper, Gould, and Zipperer 2019). Furthermore, the living wage, the amount necessary to meet minimum standards, differs across the country because the cost of living differs. Therefore, the amount of income necessary to survive in an area such as New York City differs dramatically from a small town in Oklahoma (Glasmeier 2020).

The underclass is the United States’ lowest tier. The term itself and its classification of people have been questioned, and some prominent sociologists, believe its use is either overgeneralizing or incorrect. But many economists, sociologists, government agencies, and advocacy groups recognize the growth of the underclass. Members of the underclass live mainly in inner cities or rural areas. Many are unemployed or underemployed. Those who do hold jobs typically perform menial tasks for little pay. Some of the underclass are homeless. Many rely on welfare systems to provide food, medical care, and housing assistance, which often does not cover all their basic needs. The underclass have more stress, poorer health, and suffer crises fairly regularly.

8.4.4 Poverty

In the United States, poverty is most often referred to as a relative rather than absolute measurement. Absolute poverty is an economic condition in which a family or individual cannot afford basic necessities, such as food and shelter, so that day-to-day survival is in jeopardy. Relative poverty is an economic condition in which a family or individuals have 50 percent income less than the average median income. This income is sometimes called the poverty level or the poverty line.

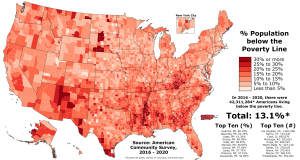

The Social Security Administration established the official poverty line in the 1960s as a way to measure the number of people living in poverty and to assess how much it changed. In the United States the official definition is the federal poverty line (figure 8.5). It indicates the total annual income below which a family would be impoverished. It is based on a minimum family food budget and assumes the average low income family spends a third of their income on food. The official poverty rate in 2020 was 11.4 percent of the U.S. population, which equates to about 37.2 million people (Shrider et al. 2021).

There has been continuing debate about the poverty line. Conservatives argue that if benefits provided to poor people, such as Medicaid, subsidized housing, reduced price school lunches, are included in the measure, then the extent of poverty is much less than reported. Liberals argue the federal poverty line underestimates poverty and that the thresholds are too low. They point to other costs in addition to food, such as childcare, heating, housing, that should be incorporated into the measure. There are also regional differences in the cost of living, and therefore the poverty line neglects poor people in expensive cities.

Demographically some groups are more likely to experience poverty than others. These include (Shrider et al. 2021):

- Single-parent families: For female-headed single-parent households, the poverty rate was 23.4 percent in 2020. For male-headed single-parent households, the poverty rate was 11.5 percent. For married couples, the poverty rate was 4.7 percent. With a couple, there is the potential for dual incomes and more options with childcare.

- Children: In 2020, 16.1 percent of children under the age 18 were living in poverty. The United States generally has lower quality childcare services than other developed countries. Without high-quality, affordable child care, it can become difficult for a parent to work steadily.

- Minority groups: While white people make up the largest group of people living in poverty (15.9 million people), minority groups disproportionately experience poverty. In 2020, 19.5 percent of black people experienced poverty, while 17 percent of Hispanics experienced poverty. This can be traced to numerous factors, such as low wages, discrimination (in housing, education, health care), and differences in education level. We will explore the influence of race on these processes in Chapter 11.

- People with disabilities: For adults (18 to 64) in 2020, 25 percent of those with a disability lived in poverty. Significant numbers of those who are poor have struggled with disabilities since childhood. A serious disability can make it hard to get a job and can hamper other aspects of life. It is important to note that poverty can lead to and worsen disabilities, but disabilities are not unique to poor families.

There are several explanations for why people become poor. A lot of Americans believe in rags-to-riches stories and the American Dream (exemplified by the sayings “if you work hard you get ahead” and “pull yourself up by the bootstraps”). From this perspective, the poor are those who failed to work hard. Poverty is seen as the result of individual laziness or lack of motivation, and the poor only have themselves to blame for their situation. Oftentimes moral or genetic deficiencies will be attributed to those experiencing poverty. You have the opportunity to learn more about commonly held myths related to poverty in the next section “Pedagogical Element: Myths of Poverty.”

Structural explanations attribute poverty to the institutions of the society, such as trends in the labor markets or corporations. It assumes poverty is a result of economic and social imbalances within the society. These can include larger forces such as severe recession, low wages, and the rise of part-time work. During severe recessions, breadwinners can lose their jobs or have their incomes reduced. People can lose their homes to foreclosure, they may use their retirement savings to live on and rack up credit card debt. When wages are low, people may not be able to cover all of their expenses. Another structural condition is the rise of part-time and gig work. These types of work receive minimal benefits and often have a minimum wage. As a result, those with jobs end up living on bare-bones budgets and have difficulty affording the basics of life.

More recently sociologists have adopted a relational perspective to understand poverty. Rather than being something individually determined or the product of social forces, poverty is seen as emerging through interactions between those who have resources and those who do not (Desmond and Western 2018). Exploitation is one of the transactional mechanisms between people that helps produce poverty. This could be owners exploiting workers, landlords exploiting tenants. Discrimination and violence also play a role in producing poverty.

8.4.5 Activity: Myths of Poverty

Poverty affects different groups in many ways. However, there are a number of misconceptions when it comes to understanding the experience of poverty and who lives in poverty.

Mark Rank, a well known sociologist who studies poverty, has identified several myths that people tend to believe about poverty. In this article, Rank describes five myths, take some time to review it: Washington Post article 5 Myths about Poverty [website]

Then discuss:

- Where do the myths originate?

- Which groups might benefit from the myths?

- Are there other myths you might add to the list?

8.4.6 Licenses and Attributions for Social Classes in the United States

First two paragraphs in “Upper Class,” first four paragraphs in “Middle Class,” first two paragraphs and last three paragraphs in “The Lower Class,” first paragraph in “Poverty” are from “9.2 Social Stratification and Mobility in the United States” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at Open Stax;https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/9-2-social-stratification-and-mobility-in-the-united-states. Edited for clarity and brevity.

All other content in this section is original content by Matthew Gougherty and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figures

Figure 8.3. Distribution of Wealth in the United States. By Delphi234. CC0 1.0. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8.4. Suburbia by David Shankbone. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8.5. Poverty in the U.S. by County. By Abbasi786786. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Via Wikimedia Commons.