9.2 Sex, Gender, and Identity

When filling out a document such as a job application or school registration form, you are often asked to provide your name, address, phone number, birth date, and sex or gender. But have you ever been asked to provide your sex and your gender?

Like most people, you may not have realized that sex and gender are not the same. However, sociologists and most other social scientists view them as conceptually distinct. Sex refers to physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity. Gender refers to behaviors, personal traits, and social positions that society attributes to being female or male.

A person’s sex, as determined by their biology, does not always correspond with their gender. Therefore, the terms sex and gender are not interchangeable. A baby who is born with male genitalia will most likely be identified as male. As a child or adult, however, they may identify with the feminine aspects of culture. Since the term sex refers to biological or physical distinctions, characteristics of sex will not vary significantly between different human societies. Generally, persons of the female sex, regardless of culture, will eventually menstruate and develop breasts that can lactate.

Characteristics of gender, on the other hand, may vary greatly between different societies. For example, in U.S. culture, it is considered feminine (or a trait of the female gender) to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, sarongs, robes, or gowns are considered masculine. The kilt worn by a Scottish man does not make him appear feminine in that culture.

Let’s explore how the language used around the concepts of sex and gender has implications at the societial level. In “Pedagogical Element: Understanding the Language of Sex and Gender” you will examine a couple of legal issues to understand how our experience of gender is socially defined by one’s culture.

9.2.1 Activity: Understanding the Language of Sex and Gender

The Legalese of Sex and Gender

The terms “sex” and “gender” have not always been differentiated in the English language. It was not until the 1950s that American and British psychologists and other professionals working with intersex and transsexual patients formally began distinguishing between sex and gender. Since then, psychological and physiological professionals have increasingly used the term gender (Moi 2005). By the end of the twentieth century, expanding the proper usage of the term gender to everyday language became more challenging—particularly where legal language is concerned.

In an effort to clarify usage of the terms sex and gender, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a 1994 briefing, “The word gender has acquired the new and useful connotation of cultural or attitudinal characteristics (as opposed to physical characteristics) distinctive to the sexes. That is to say, gender is to sex as feminine is to female and masculine is to male” (J.E.B. v. Alabama, 144 S. Ct. 1436 [1994]).

In Canada, there has not been the same formal deliberations on the legal meanings of sex and gender. The distinction between sex as a physiological attribute and gender as social attribute has been used without controversy. However, things can get a little tricky when biological sex is regarded as simply a natural fact, especially in the case of transsexuals (Cowan 2005). For example, in British Columbia, people who have surgery to change their anatomical sex can apply through the provisions of the Vital Statistics Act to have their birth certificate changed to reflect their post-operative sex.

If a person was born male, does this mean that after surgery that person is fully regarded as a female in the eyes of the law? In the 2002 case of Nixon v. Vancouver Rape Relief Society, a male to female transsexual, Kimberly Nixon brought an application to the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal that she had been discriminated against by the Vancouver Rape Relief Society (VRR) when her application to volunteer as a helper was rejected. The controversy was not over whether Kimberly was a woman, but whether she was woman enough for the position. VRR argued that as Kimberly had not grown up as a woman, she did not have the requisite lived experience as a woman in patriarchal society to counsel women rape victims. The B.C. Human Rights Tribunal ruled against VRR, finding that they had discriminated against Kimberly as a transsexual. The ruling was overturned by the Supreme Court of British Columbia, which argued that the Act ‘‘did not address all the potential legal consequences of sex reassignment surgery’’ (Cowan 2005:87). The court acknowledged that the meaning of both sex and gender vary in different contexts. The case appeal was denied (You can learn more about this case at Perpetuating the Cycle of Abuse: Feminist (Mis)Use of the Public/Private Dichotomy in the Case of Nixon v. Rape Relief [Article Abstract Webpage]).

These legal issues reveal that even human experience that is assumed to be biological and personal (such as our self-perception and behavior) is actually a socially defined variable by culture. The question of “what makes a woman” in the case of Nixon v. Vancouver Rape Relief Society is a matter of legal decision making as much as it is a matter of biology or lived experience.

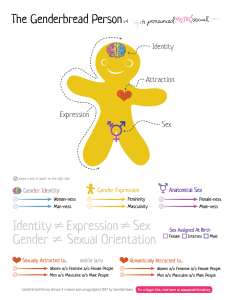

The way we use language is influenced by our culture. Culturally coded, words can also impact how we perceive gender, or more specifically roles for women and men. U.S. society allows for some level of flexibility when it comes to acting out gender roles. To a certain extent, men can assume some feminine roles and women can assume some masculine roles without interfering with their gender identity. Gender identity is a person’s deeply held internal perception of one’s gender. Gender expression, or gender presentation, is a person’s behavior, mannerisms, interests, and appearance that are associated with gender, specifically with the categories of femininity or masculinity. This can include gender roles and categories that often rely on stereotypes about gender. The graphic in figure 9.2 Genderbread Person, offers a visual to help you distinguish between gender identity and gender expression. Please keep the information offered in this graphic in mind as you learn more about gender in the next section, “Beyond the Binary.”

9.2.2 Beyond the Binary

There are different ideologies used when understanding gender. Essentialists see gender as a biological and unchanging, two-category system. They view gender as something that can be classified into distinct categories. Essentialism views chromosomes, hormones, and genitalia as key factors in determining one’s gender identity. This perspective does not create much space to account for the role of culture, how one views themselves, and how they interact with others.

Most sociologists view gender from a constructionist approach. As introduced in Chapter 4, social constructionism is the theory that all reality and meaning is subjective and created through dynamic interactions with other individuals and groups. According to this approach, gender is shaped socially and changes over time. Gender and behaviors that are associated with femininity and masculinity reflect culture and patterns of interaction that are considered normative during certain historical time periods.

The binary view of gender (the notion that someone is either male or female) is specific to certain cultures and is not universal. In some cultures, gender is viewed as fluid. Anthropologists found that among some Indigenous tribes the terms berdache or “two-spirit” people refers to individuals who occasionally or permanently dressed and lived as a different gender. Berdaches may also participate in labor roles traditionally associated with their preferred masculine or feminine style of clothing. Samoan culture accepts what Samoans refer to as a “third gender.” Fa’afafine, which translates as “the way of the woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but embody both masculine and feminine traits. Fa’afafines are considered an important part of Samoan culture. Individuals from other cultures may mislabel their sexuality because fa’afafines have a varied sexual life that may include men and women (Poasa 1992).

Gender identity may or may not correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth. Cisgender refers to those who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth are often referred to as cisgender, utilizing the Latin prefix cis-, which means “on the same side.” For example, a child is assigned female at birth and later self identifies as a woman or a child is assigned male at birth and self identifies as a man. The term cisgender does not indicate a person’s sexual orientation or gender expression.

Transgender refers to a person whose sex assigned at birth and gender identity are not necessarily the same. A transgender woman is a person who was assigned male at birth but who identifies and/or lives as a woman; a transgender man was assigned female at birth but lives as a man. While determining the size of the transgender population is difficult, it is estimated that 1.4 million adults (Herman 2016) and 2 percent of high school students in the United States identify as transgender (Johns 2019). The term transgender does not indicate sexual orientation or a particular gender expression, and we should avoid making assumptions about people’s sexual orientation based on knowledge about their gender identity (GLAAD 2021).

Some transgender individuals may undertake a process of transition, in which they move from living in a way that is more aligned with the sex assigned at birth to living in a way that is aligned with their gender identity. Transitioning may occur in the social, legal, or medical aspects of someone’s life, but not everyone undertakes any or all types of transition. Social transition may involve the person’s presentation, name, pronouns, and relationships. Legal transition can include changing their gender on government or other official documents, changing their legal name, and so on. Some people may undergo a physical or medical transition, in which they change their outward, physical, or sexual characteristics in order for their physical presentation to better align with their gender identity (UCSF Transgender Care 2019).

Not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies: many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as another gender. This is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to another gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to a gender different from their biological sex, are not necessarily transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression or personal style, and it does not indicate a person’s gender identity or that they are transgender (TSER 2021).

Actress and activist Laverne Cox, speaks publicly supporting transgender rights. Figure 9.3 shows Cox during part of her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speaking tour at California State University Fullerton . She discusses how the intersection of race, class, and gender contributes to our complex identities and how trans people in particular are affected.

Intersex is a general term used to describe people whose sex traits, reproductive anatomy, hormones, or chromosomes are different from the usual two ways human bodies develop. Some intersex traits are recognized at birth, while others are not recognizable until puberty or later in life (interACT 2021). While some intersex people have physically recognizable features that are described by specific medical terms, intersex people and newborns are healthy. Most in the medical and intersex community reject unnecessary surgeries intended to make a baby conform to a specific sex assignment. Medical ethicists indicate that any surgery to alter intersex characteristics or traits—if desired—should be delayed until an individual can decide for themselves (Behrens 2021). Intersex and transgender are not interchangeable terms; many transgender people have no intersex traits, and many intersex people do not consider themselves transgender. Some intersex people believe that intersex people should be included within the LGBTQ community, while others do not (Koyama n.d.). To learn more about intersex activism, go to Amnesty.org [website]and ISNA.org

The language of sexuality, sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression is continually changing and evolving. In order to get an overview of some of the most commonly used terms, explore the Trans Student Educational Resources Online Glossary.

When individuals do not feel comfortable identifying with the gender associated with their biological sex, then they may experience gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria is a diagnostic category in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) that describes individuals who do not identify as the gender that most people would assume they are. This dysphoria must persist for at least six months and result in significant distress or dysfunction to meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. In order for children to be assigned this diagnostic category, they must verbalize their desire to become the other gender. It is important to note that not all transgender people experience gender dysphoria, and that its diagnostic categorization is not universally accepted. For example, in 2019, the World Health Organization reclassified “gender identity disorder” as “gender incongruence,” and categorized it under sexual health rather than a mental disorder. However, health and mental health professionals indicate that the presence of the diagnostic category does assist in supporting those who need treatment or help.

People become aware that they may be transgender at different ages. Even if someone does not have a full (or even partial) understanding of gender terminology and its implications, they can still develop an awareness that their gender assigned at birth does not align with their gender identity. Society, particularly in the United States, has been reluctant to accept transgender identities at any age, but we have particular difficulty accepting those identities in children. Many people feel that children are too young to understand their feelings, and that they may “grow out of it.” And it is true that some children who verbalize their identification or desire to live as another gender may ultimately decide to live in alignment with their assigned gender. But if a child consistently describes themselves as a gender (or as both genders) and/or expresses themselves as that gender over a long period of time, their feelings cannot be attributed to going through a “phase” (Mayo Clinic 2021).

Some children, like many transgender people, may feel pressure to conform to social norms, which may lead them to suppress or hide their identity. Most children have a limited understanding of the social and societal impacts of being transgender, but they can feel strongly that they are not aligned with their assigned sex. Considering that many transgender people do not come out or begin to transition until much later in life—well into their 20s—they may live for a long time under that distress.

Queer is term used to describe gender and sexual identities other than cisgender and heterosexual. The term queer has been used in different ways and has many different meanings. Originally, a term meaning “strange” or “peculiar” came to be used in a derogatory way towards those with same-sex desires or relations in the 19th century. Starting in the late 1980s, queer activists began to reclaim the word queer and embraced it as a politically radical alternative to other LGBTQIA+ identities (Sycamore 2008). The Universalist Unitarian Association, does a good job of capturing some of the common ways queer is used today.

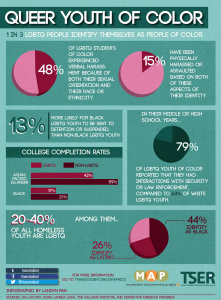

Examining the intersection of gender, sexuality, and race provides us with an opportunity to better understand inequalities within social institutions. In addition to potential conformity pressures around gender and sexulity that queer youth of color face, they may have limited social supports to help them navigate the hostile environments they encounter regularly. Nationwide, schools are hostile environments for LGBTQIA+ and gender nonconforming students of color (GSA Network 2022b). Harassment and bullying negatively affects any student’s ability to success in school, but the impact is amplified for LBGTQ youth of color as they may be bullied based on their race, sexual orientation, and gender identity at once (GSA Network 2022a).

The compounded bullying and harassment threatens one’s learning environment and feelings of safety. In a study of queer youth who identified as Hispanic/Latinx and African American/ Black youth, researchers found a disporportionally higher experience of suicidal ideations (Lardier 2020). In this study, the combination of limited social support and school bullying amplified the effect of suicidal ideations for the queer youth of color. Figure 9.5 “Queer Youth of Color” provides additional information on the percentage of youths that have experienced harrassment, assault, and houselessness.

9.2.3 Licenses and Attributions for Sex, Gender, and Identity

“Sex, Gender, & Identity” first 4 paragraphs are from “12.1 Sex, Gender, Identity, and Expression” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for consistency and brevity. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/12-1-sex-gender-identity-and-expression.

“Pedagogical Element: Understanding the Language of Sex and Gender” from “Chapter 12. Gender, Sex, and Sexuality” by William Little in OpenStax Sociology 2nd Canadian Edition, which is licensed under CC BY: 3.0. Access for free at: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology2ndedition/chapter/chapter-12-gender-sex-and-sexuality/ Edited for clarity, consistency, and brevity.

Gender expression definition adapted from Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 9.2. The Genderbread Person graphic by Sam Killerman via hues is uncopyrighted.

“Beyond the Binary” paragraphs 3-7; 9-13 are from “12.1 Sex, Gender, Identity, and Expression” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/12-1-sex-gender-identity-and-expression. Edited for clarity, consistency, and brevity.

Social constructionist definition from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.3. Photo by CSFU photos. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Figure 9.4. Photo by Shane. License: Unsplash.

Figure 9.5. Photo by Landyn Pan https://transstudent.org/graphics

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and licensed under CC BY 4.0.