9.4 Institutions and Inequalities

Throughout this chapter, we’ve examined gender as an identity, a set of ideas individuals may internalize, how our gender performances are policed, and the consequences of gendered power relations. Now let’s focus on the many ways in which gender acts to structure both our lives and opportunities. Our ideas about gender shape the world that we live in, including our social institutions. Over the past few decades, countless studies have been dedicated to examining the ways in which gender inequalities are built into the organizational structure of our social institutions. For example, we continue to see gender inequalities in education (Ballantine et al 2021), workplaces (Black 2021), and the military (Reis and Menezes 2020).

In this section of the chapter, we will turn our attention to the social institutions of family and work, but first let’s take a moment to review some of the key concepts you learned in “Examining Interactions.” We can build on that knowledge by starting to think about how gender inequalities are experienced in social institutions. Please complete the activity “Pedagogical Element: Gender Stratification” before heading to the next sections “Families” and “Social Stratification in Work/Public Sphere” where we will take a closer look at how gender inequalities are experienced within institutions.

9.4.1 Activity: Gender Stratification

In this short video, you will learn more about gender stratification. First you’ll have an opportunity to reflect on gender socialization before thinking about how gender structures our major social institutions.

Figure 9.13. Gender Stratification: Crash Course Sociology #32 [YouTube Video]

Please watch the Gender Stratification: Crash Course Sociology #32 [YouTube Video] and come back to answer the following questions:

- What does it mean when sociologists say “gender is a social construct”?

- What is gender stratification? What examples from the clip resonated with your experiences?

- How do social institutions, such as media, families, and education contribute to or perpetuate gender stratification?

9.4.2 Families

Families shape our lives and experiences of gender in fundamental ways. Legal reforms and social change created many ways for us to build our families, yet studies show us that there are some patterns when it comes to families, gender, and life chances. Research demonstrates that housework and childcare continue to be gendered, which contributes to gender inequalities within families. Keep in mind, we are discussing “families” as a broad organizing principle of daily life, not just our individual experiences in our own families. Families in this broader sense offer us a tool to understand how gender inequalities are reproduced.

9.4.2.1 Ideological and Institutional Barriers to Egalitarian Families

In our current economy, dual income households and even single-parent families far outnumber the model where one parent financially supports the entire family. This shift in family arrangements creates challenges in family members finding time after their paid jobs to maintain household responsibilities such as childcare, cleaning, and running errands. This unpaid work is referred to by sociologist Arlie Hochschild as the “second shift.” For families where there is no stay-at-home spouse, working parents need to find a way to complete many additional hours of labor to maintain a household. Through our constructions of femininity and masculinity, we develop ideas about which gender parent may be most suited to fulfill certain family roles. This leads to the feminization of household labor and a gender gap where we see more women participating in the second shift of unpaid household and childcare labor.

To learn more about the division of labor within families and how people feel about that division, Hochschild (1989) studied different families. She identified three common ideologies across families that structured their ability to engage in equal sharing of housework. Traditionalists valued the breadwinner/housewife model and believed men should primarily be responsible for earning income while women are responsible for housework and childcare. Neo-traditionalists supported the idea of women working if they desire to do so, but only if it does not interfere with her ability to take care of her family. Egalitarians preferred relationships where both partners do a fair share of earning income, housework, and childcare. Current research suggests that an egalitarian family is the preferred structure for young adults (Pedulla and Thebaud 2015, Schwartz 2022);.hHowever, the reality of these families does not always mean there is equal sharing of responsibilities (Carlson 2022).

Sociologist Kathleen Gerson, sought to understand more about decisions around household divisions of labor and gender power relations. She found that most of the people in her study (80 percent of women, 70 percent of men across all races, classes, and family backgrounds) preferred “flexible gender boundaries” where partners shared in completing both paid and unpaid work (Gerson 2010). The breadwinner model where one spouse specializes in paid labor while the other manages home life seems to be falling out of favor. However, there are ideological and institutional barriers to implementing equal sharing of housework. As you will learn in the next section, “Social Stratification in Work/Public Sphere,” factors built into the structure of work such as the pay gap and glass ceiling may limit individual choices when it comes to equal participation in the workforce. Affluent families have additional financial resources to handle some of the burdens associated with housework and childcare. They may be able to outsource some domestic work by hiring nannies, housekeepers, laundry services, and ordering prepared meals.

Another barrier to equal sharing of responsibilities within families is the ideology of intensive motherhood which remains pervasive in the United States. Intensive motherhood refers to the ideas that mothers should serve as the primary caretaker. Additionally, childrearing is viewed as an activity that requires large amounts of time, energy, and material resources that should take priority over other interests, desires, and responsibilities (Hays 1996). The ideology of intensive motherhood places great pressure on women specifically, but this model of parenting is not a cultural universal. For example, the popular Netflix show Old Enough highlights ways that families in other countries give their children, even toddlers, more responsibility and independence.

9.4.3 Social Stratification in Work/Public Spheres

As you learned in Chapter 8, stratification refers to a system in which groups of people experience unequal access to basic, yet highly valuable, social resources. There is a long history of gender stratification in the United States:

- Before 1809—Women could not execute a will

- Before 1840—Women were not allowed to own or control property

- Before 1920—Women were not permitted to vote

- Before 1963—Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work

- Before 1973—Women did not have the right to a safe and legal abortion (Imbornoni 2009)

When looking to the past, it would appear that society has made great strides in terms of abolishing some of the most blatant forms of gender inequality but underlying effects of male dominance still permeate many aspects of society.

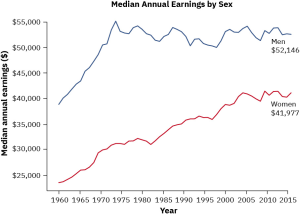

9.4.3.1 The Pay Gap

Despite making up nearly half (49.8 percent) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber women in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Even when a woman’s employment status is equal to a man’s, she will experience what’s known as a pay gap: generally a woman makes only 81 cents for every dollar made by her male counterpart (Payscale 2020). Women in the paid labor force also still do the majority of the unpaid work at home. On an average day, 84 percent of women (compared to 67 percent of men) spend time doing household management activities (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). This double duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure (Hochschild and Machung 1989). You can learn more at AAUW [website].

Part of the gender pay gap can be attributed to unique barriers faced by women regarding work experience and promotion opportunities. A mother of young children is more likely to drop out of the labor force for several years or work on a reduced schedule than is the father. As a result, women in their 30s and 40s are likely, on average, to have less job experience than men. This effect becomes more evident when considering the pay rates of two groups of women: those who did not leave the workforce and those who did. In the United States, childless women with the same education and experience levels as men are typically paid in amounts close to but not exactly the same as men. However, women with families and children are paid less. Employers offer mothers a 7.9 percent lower starting salary than non-mothers, which is 8.6 percent lower than men (Correll et al 2007).

Further, not all states have laws that prohibit employers from discriminating against LGBTQIA+ individuals when it comes to hiring practices and wages (Gates 2017). In a survey research by Singh and Durso (2017) demonstrates that there is a high rate of discrimination for LGBTQIA+ workers. They found that 27 percent of transgender workers reproted being fired, not hired, or denied a promotion because of their gender identities.

9.4.3.2 The Glass Ceiling

The idea that women are unable to reach the executive suite is known as the glass ceiling. It is an invisible barrier that women encounter when trying to win jobs in the highest level of business. At the beginning of 2021, for example, a record 41 of the world’s largest 500 companies were run by women. While a vast improvement over the number twenty years earlier—where only two of the companies were run by women—these 41 chief executives still only represent eight percent of those large companies (Newcomb 2020).

Why do women have a more difficult time reaching the top of a company? One idea is that there is still a stereotype in the United States that women aren’t aggressive enough to handle the boardroom (Reiners 2019). Other issues stem from the gender biases based on gender roles and motherhood discussed above. Another idea is that women lack mentors, executives who take an interest and get them into the right meetings and introduce them to the right people to succeed (Murrell and Blake-Beard 2017).

9.4.3.3 Feminization of Poverty

The gendered gap in wages, the higher proportion of single mothers compared to single fathers, and the high cost of childcare create a gendered experience when it comes to living in poverty. Considering the economic situation produced by these factors, women (11%) are more likely to live in poverty than men (8%) (Fins 2020).Women in all racial and ethnic groups are more likely than white men to live in poverty. United States census data shows that poverty rates are higher for black women (18%), Native American women (18%), Latinx women (15%), and Asian women (8%) (Fins 2020).

9.4.3.4 Women in Politics

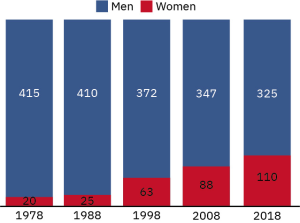

One of the most important places for women to help other women is in politics. Historically in the United States, like many other institutions, political representation has been mostly made up of White men. By not having women in government, their issues are being decided by people that might not share their perspective. The number of women elected to serve in Congress has increased over the years, but does not yet accurately reflect the general population. For example, in 2021, the population of the United States was 49 percent male and 51 percent female (Census.gov 2022), but the population of Congress was 72.3 percent male and 27.7 percent female (Manning 2022). Over the years, the number of women in the federal government has increased, but until it accurately reflects the population, there will be inequalities in our laws.

9.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Institutions and Inequalities

“Institutions and Inequalities” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Pedagogical Element: Gender Stratification” adapted from Gender Stratification: Crash Course Sociology #32 by Crash Course Sociology. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

“Families” by Jennifer Puentes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Social Stratification in Work/Public Spheres” paragraphs 1-3, 5-6, 8 edited for clarity, consistency, and to update content from “12.2 Gender and Gender Inequality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/12-2-gender-and-gender-inequality

All other content in this section is original content by Jennifer Puentes and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.14. Image by licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.15. Image by licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Image Description for Figure 9.15:

Columns are shown for the years 1982, 1992, 2002, 2012, and 2022. Each column shows the number of men versus women in Congress. In 1982, there were 23 women and 512 men in Congress. In 1992, there were 32 women and 503 men. In 2002, there were 72 women and 463 men. In 2012, there were 90 women and 445 men. In 2022, there were 147 women and 388 men.

[Return to Figure 9.15]