2.3 Social Change and the Sociological Framework

All sociologists are interested in individuals’ experiences and how interactions with social groups and society shape those experiences. To a sociologist, an individual’s personal decisions do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns, social forces, and influences pressure people to select one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behavior of groups of people living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures.

For example, most United States residents probably agree that we enjoy a great deal of freedom. Yet perhaps we have less freedom than we think because society influences many of our choices in ways we do not even realize. Perhaps we are not as distinctively individualistic as we believe we are.

Think back to the last time you rode in an elevator. Why did you not face the back? Why did you not sit on the floor? Why did you not start singing? Children can do these things and “get away with it,” because they look cute doing so, but adults risk looking odd. Because of that, even though we are “allowed” to act strangely in an elevator, we do not (figure 2.4).

We also know that, even though we learned how to ride an elevator a certain way, we are susceptible to the actions of others. Watch the 2:14-minute video, “Elevator Psychology – Social Influence” (figure 2.5). It’s a clip from the 1960s television program Candid Camera. As you watch, imagine why the Candid Camera “stars” (the ones not aware of the experiment) follow the actions of the other elevator passengers.

There are many ways to approach sociology and understand our fascinating social behaviors, whether we are in an elevator or on the soccer field. However, understanding how social influences affect human behavior is the basis for understanding how society changes. This section will explore a few frameworks that shape sociology: sociological imagination, the social construction of reality, and the debunking motif.

Sociological Imagination

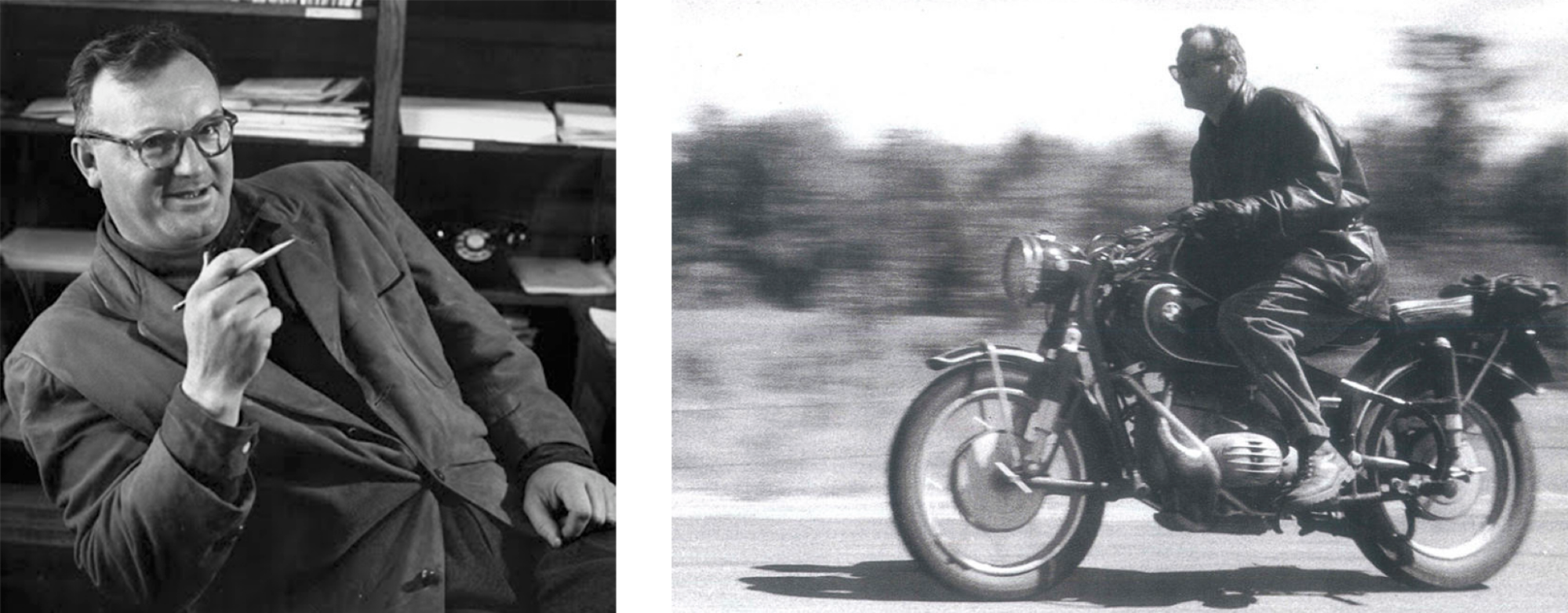

C. Wright Mills (figure 2.6) coined the term sociological imagination, an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shaped the person’s choices and perceptions. In other words, sociological imagination is “the ability to look beyond the individual as the cause for success and failure and see the society in which one lives as the cause” (Mills 1959).

This framework helps us examine how people’s experiences differ according to their place in society and the limitations and opportunities they experience as a result. The sociological imagination allows us to make connections between our personal experiences and the broader forces that impact us. Those forces may be economic, political, cultural, familial, educational, or environmental. They each influence the world we see, the opportunities available to us, and the challenges we face. Watch the 2:28-minute film “The Sociological Imagination

” (figure 2.7). As you do, consider the following: In what ways are you already using your sociological imagination?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZDYSNgaCNQ

Social Construction of Reality

The social construction of reality is another common framework for understanding society. When sociologists explain that something is socially constructed, they mean that as members of society, we decide the meaning and value of behaviors, ideas, or objects. This process is ongoing and happens through our everyday social interactions.

By creating meaning and value for ideas, objects, or actions, we make sense of the world, convey this understanding to others, and find ways of sharing those understandings. In turn, we can observe the consequences of that social construction (positive, negative, or neutral). Consider the various meanings people attach to the U.S. flag. For some, the flag represents hope, freedom, and life earned through courage and bravery. For others, the flag creates a sense of conflict because it is sometimes flown by white supremacist groups that call for racial exclusion. Interactions with others created each of those meanings associated with the U.S. flag.

Another good way to see social construction is through the lens of crimes. How many of us stop to think about how the crimes we commit every day have come into being? What’s that—you say you don’t commit crimes every day? A look at the “Charter, Code and Policies” page of the City of Portland, Oregon’s website might reveal a different story (figure 2.8). Among other regulations, it is a crime to jaywalk. Specifically, it is a crime to cross a street other than within a crosswalk “if within 150 feet of a crosswalk.” It is also a criminal act if you don’t cross a street at a right angle unless crossing within a crosswalk.

Portland is not unique in its pedestrian regulations. Many cities have similar laws that residents are not immediately aware of. Some are very curious. For example, in Las Cruces, New Mexico, you may not carry a lunchbox down Main Street (Davison 2023). In Maryland, it is a violation to be in a public park with a sleeveless shirt (Stephenson 2011). And in Asheville, North Carolina, it is illegal to sneeze on city streets (Byrd 2015). Granted, many of these are from many years ago, when practices were very different, and most of these laws are not enforced. However, at one tim,e some members of societies attached meaning to these behaviors that deemed them criminal acts.

When we look at crime through the idea of social construction, we see that society has given certain meanings to our actions. This helps us step back, think about how society works, and ask the following questions:

- Who distinguishes what behavior is a criminal act?

- Who determines which laws will be enforced, and how?

- Who decides which members of society violating those laws are pursued and punished?

These kinds of questions help us wrestle with our society’s inequities and begin to imagine ways to change them.

In the case of jaywalking, the U.S. government began to discourage the behavior in the early 1900s. As more people were buying motor vehicles, officials wanted to prevent pedestrians from crossing wherever convenient for safety reasons. Later, the auto industry joined the campaign to make city streets more welcoming to drivers as part of their promotion of the automobile. Communications included shaming and ostracizing people who did not follow the rules (figure 2.9 [left]).

Today, some criticize jaywalking laws as justification for police to stop pedestrians, especially in Black and brown communities (figure 2.9 [right]). We know that police in many areas disproportionately stop people of color (Carvalho et al. 2021). For example, in Washington state, Black pedestrians are stopped by police for jaywalking 4.7 times more frequently than their share of the population (Campbell 2024).

While many of our laws related to criminal activity were implemented decades ago, they still reflect how we interact. Laws about how we punish people for crimes also reflect historical and current inequities. In 2022, Oregon only narrowly voted to strip language from its constitution that allows for slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. Four states had similar initiatives on the ballot that year.

The language goes back to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery. Some states made exceptions to allow slavery as a punishment for a crime. As a result, Black United States residents continued to be arrested under false pretenses after the Civil War, allowing slavery to continue (Bogel-Burroughs 2022; Wilson 2022). Today, because the law allows for prisoners to be forced into labor for little or no pay, it’s worth asking if this law means our system of slavery still exists.

The Debunking Motif

Another key tool used to understand the foundations of society is the debunking motif. As Peter L. Berger noted in his classic book Invitation to Sociology, “The first wisdom of sociology is this—things are not what they seem” (Berger 1963:23–24). Social reality, he said, has “many layers of meaning,” and sociology aims to help us discover these multiple meanings. He continued, “People who like to avoid shocking discoveries…should stay away from sociology.”

As Berger emphasized, sociology helps us see through conventional understandings of how society works. By “looking for levels of reality other than those given in the official interpretations of society” (Berger 1963:38), Berger said, sociology looks beyond surface understandings of social reality. It helps us recognize the value of alternative understandings. In this manner, sociology often challenges conventional understandings of social reality and social institutions.

Licenses and Attributions for Social Change and the Sociological Framework

Open Content, Original

“Social Change and the Sociological Framework” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“‘Social Change and the Sociological Framework’, paragraph 1” is adapted from “1.1 What Is Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0: summarized some content and applied it specifically to social change.

“‘Social Change and the Sociological Framework,’ paragraph 2” is adapted from “1.1 The Sociological Perspective” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include adding photo, video, and explanatory text.

Figure 2.4. Woman Holding Elevator by WNYC New York Public Radio is licensed under CC-BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 2.6. “C. Wright Mills” by Gambar Fritz Goro is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 (left).

“The Debunking Motif” is adapted from “1.2 Understanding Society” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

Figure 2.9. “Don’t Jay Walk; Watch Your Step,” on Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain (left).

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.5. “6 – Candid Camera (Elevator)” by ATW Training is licensed under the Vimeo Terms of Service.

Figure 2.6. “C. Wright Mills” by Yaroslava Mills is found in “C. WRIGHT MILLS,” in

the UC Press E-Books Collection and included under fair use (right).

Figure 2.7. “The Sociological Imagination” by Andrew Reszitnyk is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.8. “City of Portland’s Crosswalk Regulations Screenshot” by City of Portland is included under fair use.

Figure 2.9b. “Legalize Safe Crossings” is found as a poster on the Calbike web site and is included as fair use (right).

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.