6.4 Sociological Perspectives on Economic Change

Sociology emerged as an academic discipline asking questions about why capitalism and, more generally, modern society emerged. Early sociologists also wanted to understand some of the consequences of capitalism on people’s lives. So there are a huge number of thoughtful answers to those questions. We’ll focus on exploring the perspectives of two foundational thinkers within the discipline: Karl Marx and Max Weber.

Karl Marx’s Theory of Historical Materialism

Karl Marx is famous as one of the key intellectuals of the communist movement and the lead author of the Communist Manifesto [Website] (Marx and Engels 1848). Whatever you think of his ideas or his politics, he has arguably influenced the course of history as much as any other theorist in the last 200 years.

The most important thing to understand about Marx is that he’s a “historical materialist.” In social theory, historical materialism is a perspective that emphasizes the economy in explaining just about everything in society. For Marx, the economic system is the base, or foundation, of society.

Marx believed that almost all economic systems (and most social structures) are rooted in class conflict. Class conflict refers to the structural oppositions built into economic relationships. For example, the economic system of slavery in the United States was built on an exploitative conflict between two groups: enslavers and enslaved people. Enslaved people produced much of the wealth of the society by doing the labor. The enslaver class took the wealth produced by enslaved people. In that sense, the enslaver class is a non-productive consumer of the wealth produced by others (Marx 1976).

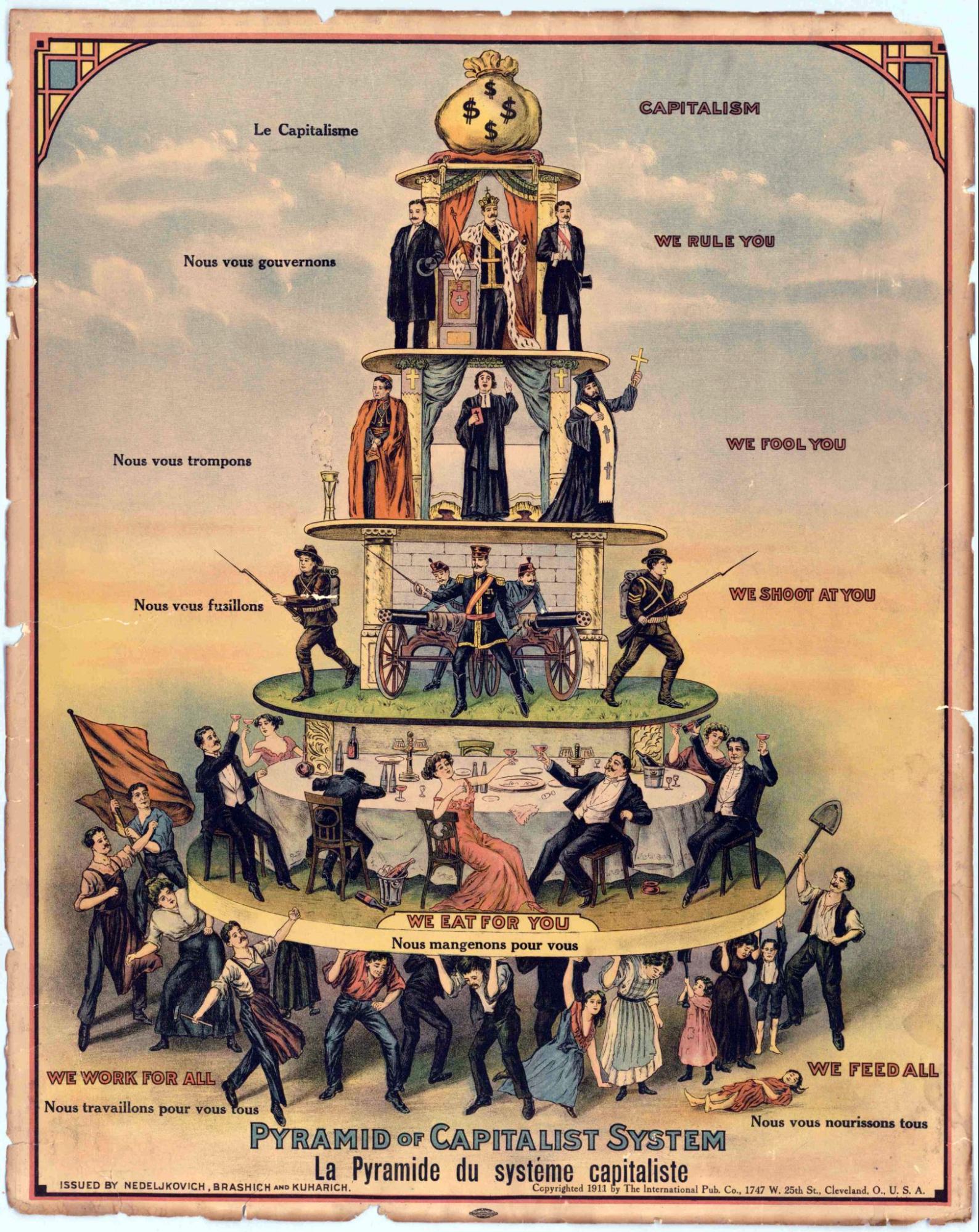

Note that this economic conflict, according to Marx, is structural—it is built into the very fabric of the economy, as shown in figure 6.5. It isn’t just that the enslaved person and the enslaver didn’t like each other. The economic systems—the social structure itself—set them at odds. The only way to end that conflict is to abolish that economic structure and create a different kind of economy. This basic dynamic of conflict, says Marx, also operates in other economic systems, like feudalism.

Marx argues that our economic system—capitalism—is governed by these same principles. Those who own the factories and businesses (the owning class, or bourgeoisie) use the labor of the working class (the proletariat) to produce wealth. And Marx argues that the owning class can only profit when they pay workers less than their actual value—that is, when they exploit them. The less the owners pay the workers, the more they keep in profits. For Marx, this conflict between workers and owners is the core of modern society. And like all economic conflicts, it will eventually erupt and cause social change.

Marx suggests that class conflict is, in fact, the driving force of social change and progress. Social changes that arise will eventually result in the creation of a new economic system. This creates a kind of cycle of conflict, which pushes progress forward. History, he says, is a series of class conflicts.

Marx’s theories are influential today, not just because they illuminate important conflicts rooted in our own economic system and our social structure but also because his emphasis on conflict has inspired many other theorists to explore power and inequality related to empire, race, gender, and sexuality.

Max Weber and the Protestant Ethic

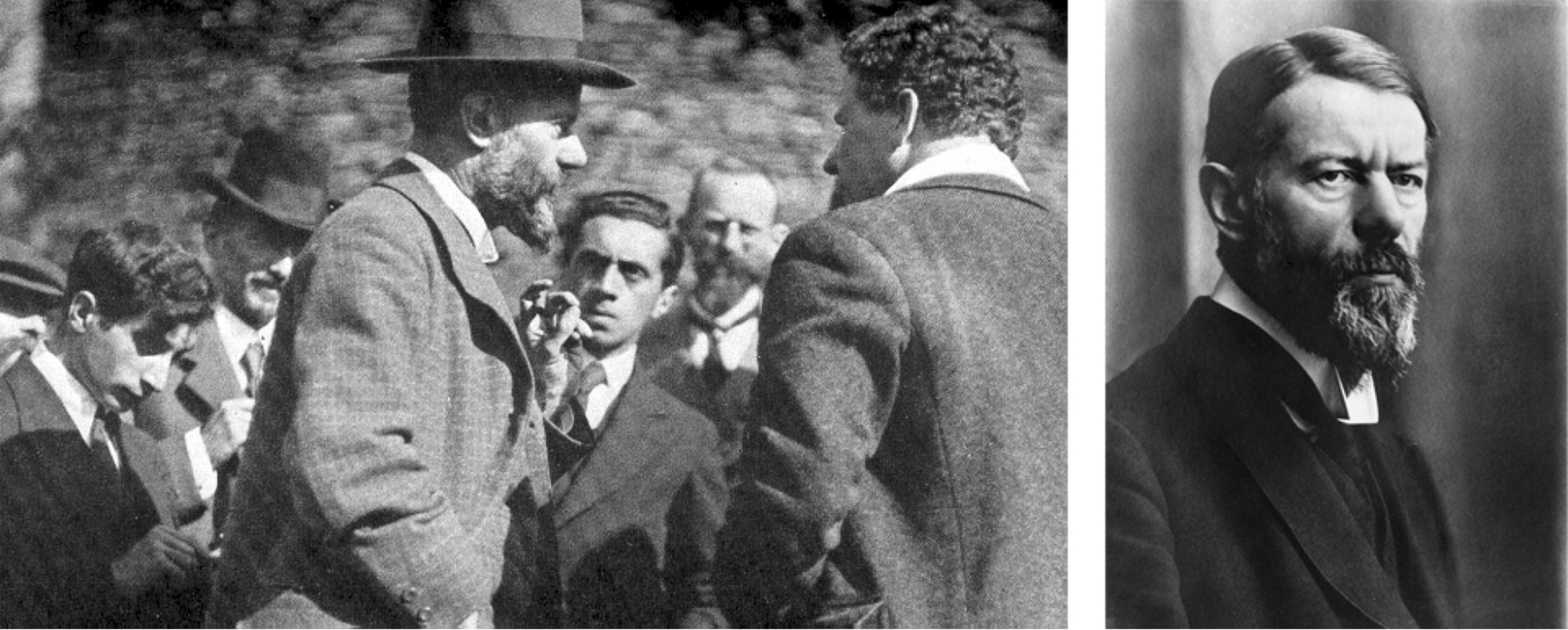

Max Weber was a German sociologist in the early 1900s (figure 6.6). Like Marx, Weber was interested in the rise of capitalism. But unlike Marx, Weber highlighted the role of cultural beliefs in capitalism’s emergence. Weber was especially interested in the role of changing religious beliefs within Christianity.

He noted that the Protestant Reformation—a 16th-century religious movement led by German theologian Martin Luther—changed the way many people thought about work and wealth. The Protestant ethic is a set of cultural and religious beliefs that Weber argued laid the cultural groundwork for the rise of capitalism (Weber 1992).

So how did Protestant values enable the rise of capitalism? A significant aspect of the answer relates to how people viewed work.

Prior to the Protestant Reformation, most Europeans understood work in secular, or non-religious, terms. Sure, members of the Catholic clergy did sacred work, but everybody else did work that wasn’t steeped in religious meaning. If a person were a cobbler, they made shoes because they needed income, or because their father did it, or because they enjoyed the labor, but not because God wanted them to. That changed after the Protestant Reformation.

Weber points out that Protestantism extended “the calling” to all people, not just members of the clergy. A calling is a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life. That meant that God didn’t just call some people to the priesthood; he called all people to their labor. If a person was a cobbler, that was now their “calling.”

But why should that matter? Weber argued that in extending the calling, Protestantism imbued all labor with deep moral purpose. Now, one didn’t just make shoes because they needed to pay the rent: they made shoes as part of their sacred duty to God. Hard work, then, became a virtue, since it showed a person’s commitment to their calling. Even more, since Protestantism did not use the ritual of confession, hard work became a way for people to show their commitment to God and, perhaps, gain forgiveness for their sins. Hard work became the substitute for confession (Allan 2007).

Protestantism also encouraged thrift and modesty and discouraged the faithful from spending money on luxuries. So if a person’s hard labor earned them profits, they should not spend those profits frivolously. Instead, they should reinvest their profits into the work to which God has called them.

In short, Protestantism redefined work, giving it a new moral weight. It also encouraged people to reinvest their profits into their work. Weber suggested that these new religious beliefs created fertile conditions for capitalism to develop (Allan 2007).

Going Deeper

Listen to the 58-minute podcast “Capitalism: What Is It?” [Website] to hear three experts debate the merits of capitalism today. Keep these questions in mind as you listen:

- Do you notice any discrepancies between widespread cultural beliefs about the economy (like individual responsibility and economic opportunity) and economic realities?

- How do these different scholars understand the role of social forces in shaping an individual’s life experience?

- Given what you’ve read so far in this chapter, can you identify the theoretical perspectives of each scholar?

For some thorough notes on the difference between capitalism and socialism, watch this video by animateeducate [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for Types of Economies

Open Content, Original

“Sociological Perspectives on Economic Change” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Image 6.6 added by Aimee Samara Krouskop.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.5. “Pyramid of Capitalist System Poster” by Nedeljkovich, Brashich, and Kuharich, published by The International Pub. Co., is on Wikipedia and in the public domain.

Figure 6.6. Max Weber in discussion, at the Lauenstein conference in Germany is on Wikipedia and in the public domain (left). Portrait of Max Weber is on Wikipedia and in the public domain (right).

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.

a perspective that emphasizes the economy in explaining just about everything in society, and sees economic class conflicts as main drivers of social change and progress.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the structural antagonisms built into economic relationships.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a set of cultural and religious beliefs that value hard work, thrift, and efficiency in one's worldly calling. It was theorized by Max Weber to have laid the groundwork for the rise of capitalism in modern Western society.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

an economic system in which the means of production and natural resources are collectively owned, usually controlled by the government.