3.4 Systems of Oppression

Aimee Samara Krouskop and Kimberly Puttman

Social location profoundly affects the opportunities of groups and individuals because of inequality. However, the concept “systems of oppression” can help us to identify harmful historical, current, and organized patterns of interactions across social locations.

Oppression refers to the systemic, extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness. It is a combination of discrimination, personal bias, bigotry, and social prejudice that leads to burdensome, cruel, unjust, or unfair treatment of groups. This includes the denial of rights, opportunities, and resources. Oppression includes overt acts of force and violence, as well as subtle and systemic forms of limitations, disadvantages, or disapproval.

The “Talking About Race” project with the National Museum of African American History and Culture explains that:

In the United States, systems of oppression are woven into the very foundation of American culture, society, and laws. Institutions, such as government or education, and larger social systems such as culture all contribute or reinforce the oppression of some social groups while elevating others. Examples of systems of oppression are sexism, heterosexism, ableism, classism, and ageism (National Museum of African American History and Culture n.d.).

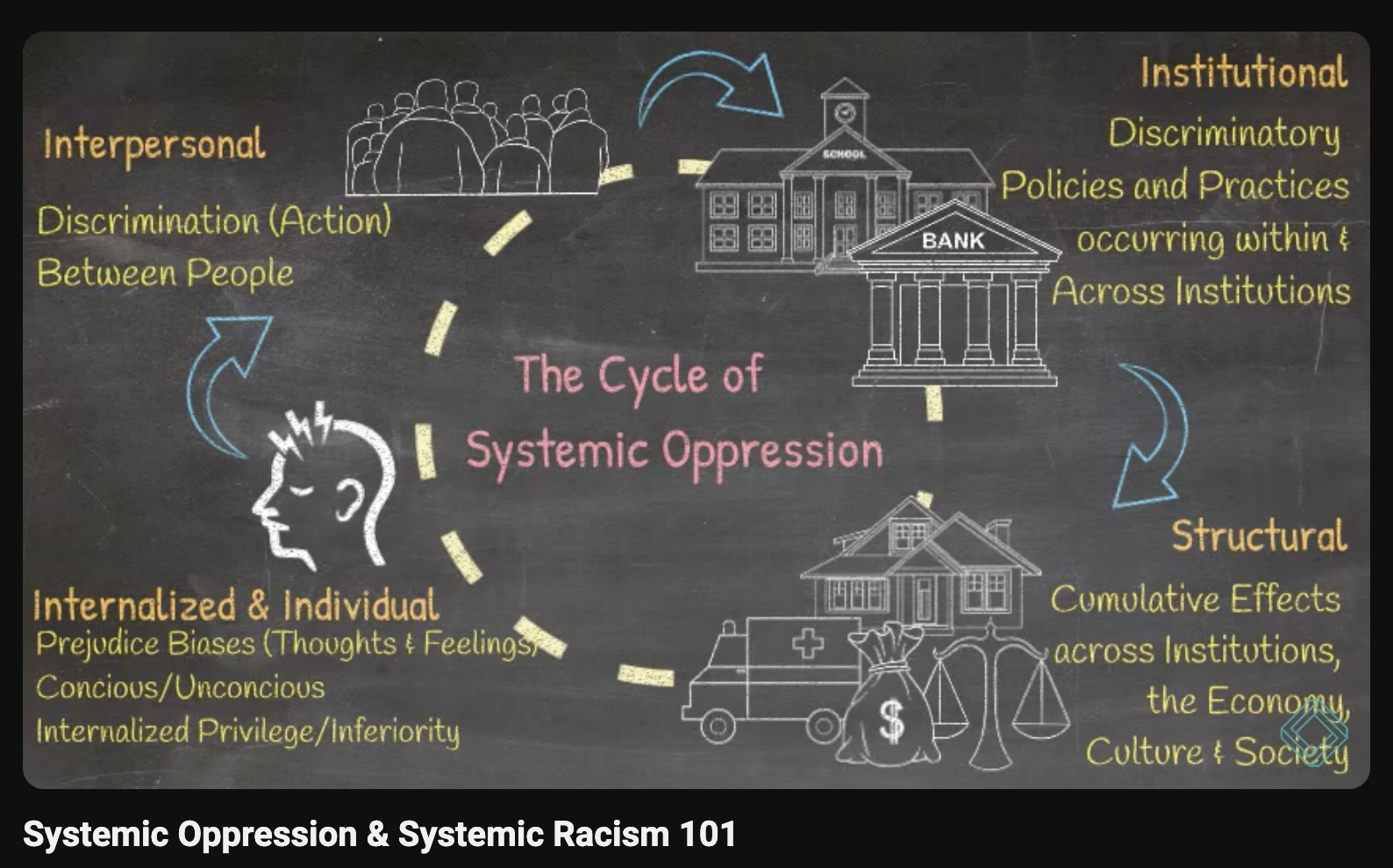

We can examine oppression at all levels of analysis. The image in figure 3.12 offers another way to look at those levels in the context of oppression: Internalized and Individual, Interpersonal, Institutional, and Structural. This section will explore some ways that oppression shows up in the United States at these various levels. We’ll explore how power creates inequity; how to consider intersectionality; how white culture contributes to institutional racism; and the role of normalization in oppressing gender identity, sexual orientation, and their expressions.

Power, Inequality, and Inequity

In navigating our social locations and the systems of oppression in society, we are also navigating the historical and contemporary relationships of power and privilege between groups. By “power,” we mean two things: 1) access to and through various social institutions; and 2) processes of privileging, normalizing, and valuing certain identities over others. This definition of power highlights the structural, institutional nature of power, while also highlighting the ways in which culture works in the creation and privileging of certain categories of people. Power is organized along the axes of gender, race, class, sexuality, ability, age, nation, and religious identities.

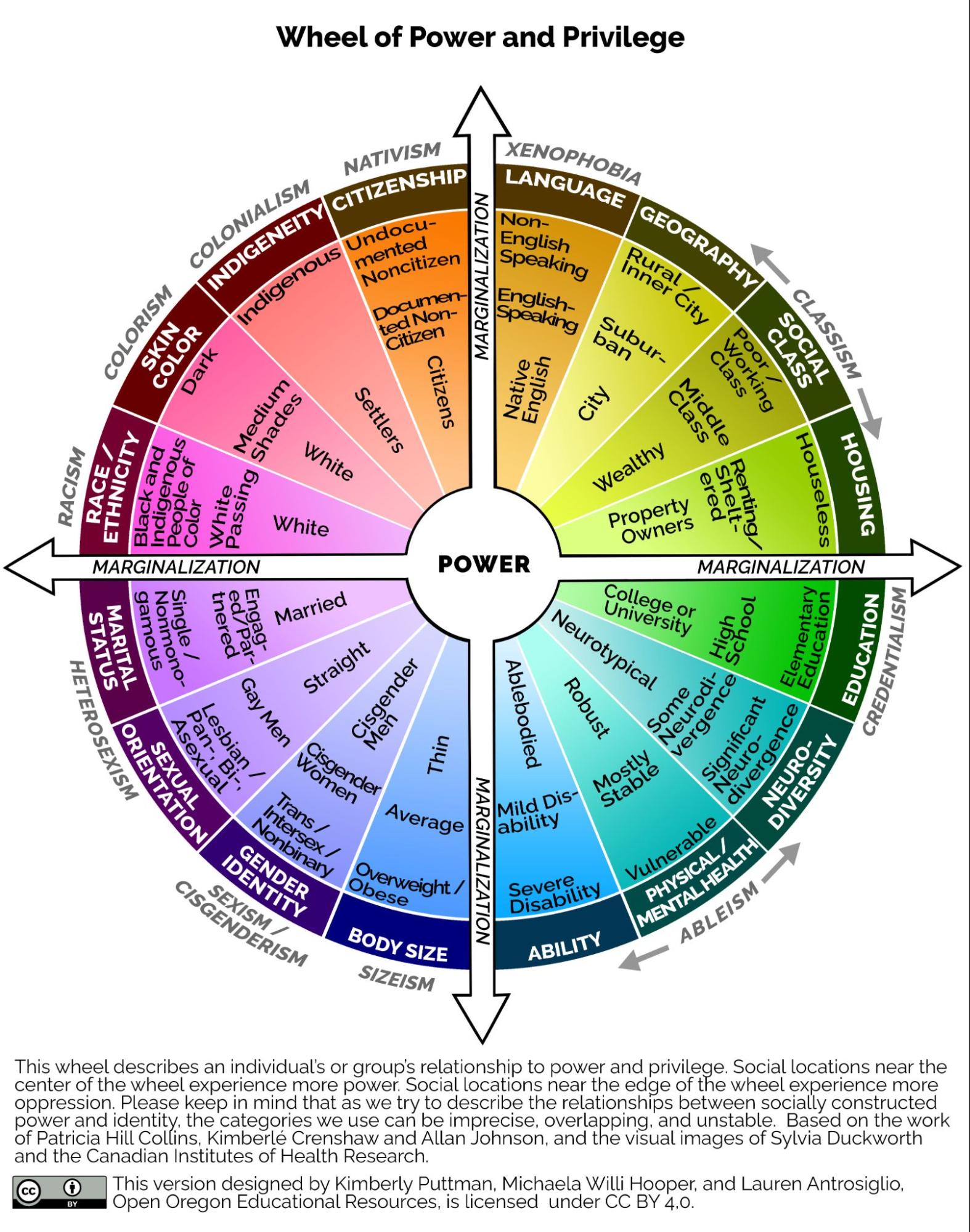

Take a look at the image in figure 3.13. It adds to the image of social identities in figure 3.6 and depicts how our social identities intersect to shape the power and privilege we hold in society. Imagine each concentric piece as a movable wheel, creating a variety of experiences for individuals based on their combined social characteristics. Where can you find yourself and your experiences on the wheel?

All individuals have multiple aspects of identity. Their social place and associated power are shaped by the privileges and advantages attached to those identities. Thus, a white, heterosexual, middle-class woman may be disadvantaged compared to a white, middle-class man, but she may experience advantages in different contexts in relation to a black, heterosexual, middle-class woman or a white, heterosexual, working-class man or a white, lesbian, upper-class woman.

Those with identities and life experiences listed toward the outer edges of the wheel will generally experience less power and privilege than those who identify with experiences in the center. At the far edges of the wheel are the kinds of discriminations and prejudices; the oppressions experienced by people with those identities and life experiences.

With this understanding of power and privilege, we can distinguish between inequality and inequity. Inequality refers to differences in access to resources, treatment, or opportunity between individuals or groups. Inequity refers to differences in access to resources or opportunity, but those differences are the result of treatment by a more powerful group. This creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair. In instances of inequity, there is a social group with power that is acting (or failing to act) in a way that denies the needs of another group and creates unfairness for them.

Intersectionality

Many people experience oppression based on multiple social identities, causing compounding hardship. This overlapping of oppressed groups was the focus of Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, a U.S. civil rights advocate and law professor. She coined the term “intersectionality” in the 1980s to present a framework for noticing the ways that gender and race have been historically separated into separate fields of study. It also served to describe how Black women faced heightened struggles and suffering in U.S. society because they belonged to multiple oppressed social groups.

Intersectionality is the observation that inequalities produced by multiple and interconnected social characteristics influence the life of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, and sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

Intersectionality studies have their origins in the Combahee River Collective. The collective was founded in 1974 by a group of Black feminist women in the United States who challenged how white feminist and civil rights movements did not address the needs of Black women. Much of the research in this field has its roots not just in academic discourse but also in attempts to initiate social change. The theory of intersectionality reflects multiple perspectives, places emphasis on lived experiences, and creates visibility around perspectives of marginalized groups. In this way, issues of discrimination, ageism, classism, and others can be seen in the multilayered circumstances where they exist.

Watch this 5:47-minute video, “Kimberlé Crenshaw at Ted + Animation” [Streaming Video] (figure 3.14), for her explanation of the importance of seeing our interactions with intersectionality. Can you think of an instance like Emma’s in the video that is best seen through the lens of intersectionality?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JRci2V8PxW4&t=357s

Examining the intersection of gender, sexuality, and race provides us with an opportunity to better understand inequalities within social institutions.

White Culture and Institutional Racism

Although race has no genetic or scientific basis, the concept of race is profoundly consequential. Statistically, education, income, birth rates, and life expectancies all vary between racial and ethnic groups. People of color tend to have shorter lifespans because of limited access to health care and lower-income jobs that can have greater dangers in the workplace. Specific racial groups are more likely to be targeted for violent events, such as when members of law enforcement disproportionally apply force, when corporations or governments cause displacement, or in cases of genocide. Let’s narrow our focus to white culture and institutional racism in the United States.

White people in the United States hold most of the political, institutional, and economic power, and they receive advantages that nonwhite groups do not. These benefits and advantages are known as white privilege. Scholar Peggy McIntosh writes, “White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, code books, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks” (McIntosh 2003). White people can experience hardship related to other parts of their identity, but their race is not one of these.

White privilege in the United States has its foundations in white supremacy, the ideology that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups. This false notion is rooted in pseudo-science that has been used to justify slavery, colonialism, and genocide at various times throughout history. White superiority has been part of the United States since its inception as a country.

These beliefs justified both the atrocities of the genocide of Native Americans and nearly 250 years of African slavery. In later chapters of this book, we’ll discuss how white supremacist ideologies continued after slavery into laws that limited the freedom of African Americans. We’ll also explore how white supremacy can still be found in our legal system and other institutions through coded language and targeted practices.

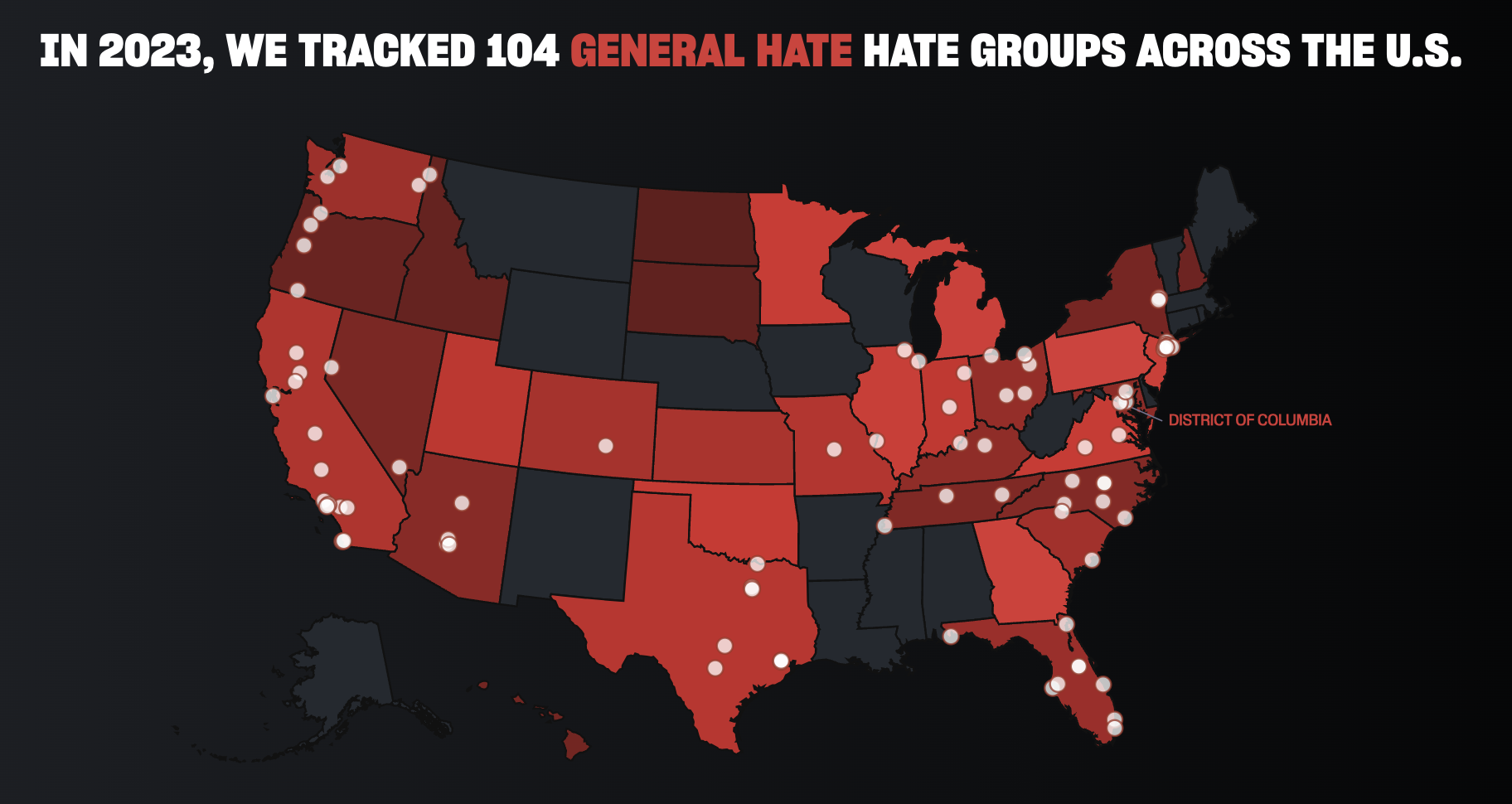

Explicit expressions of white supremacy are evident today in organized groups such as the white nationalist hate group Patriot Front. In those groups, followers continue to perpetuate the myth of white racial superiority. Direct and violent forms of racism that promote white supremacy have been on the rise in recent years. These acts are more directly linked to white nationalism, the belief that one’s country is only for the white race. They also believe that the diversity of people in the United States will lead to the destruction of whiteness and white culture. Take a brief look at the map at the Southern Poverty Law [Website] center, which tracks the 104 hate groups in the United States (you can filter by ideology) (figure 3.15). Does anything surprise you about groups in your state?

Extremist groups are what most people think of when they consider white supremacy. However, the ideology of white supremacy permeates beyond extremist groups in more subtle and widespread ways. As residents in the United States, we exist in a white dominant culture. White people and their practices, beliefs, and culture are normalized and the standard by which all other groups are compared. This white dominant culture automatically centers (gives central focus to) the experiences and priorities of white lives.

The impacts of such a dominant culture of whiteness exist in various ways. Let’s look back at figure 3.12 to make some connections. At the Internalized & Individual levels, dominant white culture provides advantages to white people, since they can navigate society both by feeling normal and being viewed as normal. The pages of the National Museum of African American History and Culture explain that:

Persons who identify as white rarely have to think about their racial identity and their cultural expressions because they live within a culture where whiteness has been normalized. Thinking about race is very different for nonwhite persons living in America. People of color must always consider their racial identity, whatever the situation (National Museum of African American History and Culture n.d.).

Or, in the words of Toni Morrison, “In this country, American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate” (Morrison 2000) (figure 3.16).

At the Interpersonal level, people of color experience microaggressions when others reveal their biases against them. Microaggressions include verbal or nonverbal slights, snubs, or insults. At a Structural level, societies use race to establish and justify systems of power, privilege, and disenfranchisement through Institutional bodies such as health care, education, and housing. This results in nonwhite persons having less access and opportunity in society.

Three other impacts of white supremacy that are important to distinguish are racism, institutional racism, and structural racism. Racism begins when someone is prejudiced in thought or action, then accompanies that thought or action with their power to discriminate against, oppress, or limit the rights of others. Institutional racism occurs within institutions and systems of power. It refers to the unfair policies and discriminatory practices of particular institutions (e.g., schools, workplaces) that routinely produce racially inequitable outcomes for people of color and advantages for white people. Individuals can practice racism within institutions.

Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton introduced the idea of institutional racism in their book Black Power: Politics of Liberation in America after they sought to explain the prevalence of Black families in slums and the high rates of Black infant mortality in Birmingham, Alabama. In 1967, the year the book was published, Hamilton discussed institutional racism with broadcaster Studs Terkel. He explained:

We went to school. It was called a school of slavery and a school of segregation. And the lessons were very clear.…You hate yourself. You are supposed to hate yourself because you are a quote “minority,” you are different. You are lazy, apathetic, and so forth. And you pass out of this school and pass those lessons to the extent that you believe this, you see.

Now a lot of people in this country, white and Black, really don’t believe that. They don’t believe that the system deliberately did this to us. Because they individually have never insisted that a Black man hate himself, you know. And they personally have never really hanged or lynched a Black man recently, you know. But that is not the point.…The point we are trying to make in this book is that one’s individual stance in relationship to the Black man is irrelevant. It’s what the system does, and that’s why we use the term “institutional racism” (Terkel 1967).

Structural racism is the system of racial bias that exists in institutions and society. During a roundtable meeting in 2000 the Aspen Institute developed this explanation:

….public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. (Structural racism) identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with “whiteness” and disadvantages associated with “color” to endure and adapt over time. Structural racism is not something that a few people or institutions choose to practice. Instead it has been a feature of the social, economic and political systems in which we all exist (Aspen Institute n.d).

Understanding the framework of institutional and structural racism is essential for understanding how racism is organized in the United States, as racism amounts to more than individual acts of discrimination. However, more importantly, as Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton shared in their interview, institutional and structural racism impact individuals profoundly.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is an author, journalist, and activist. He has gained a wide readership as he writes about cultural, social, and political issues, particularly regarding African Americans, white supremacy, and racism (figure 3.17). Coates’s book Between the World and Me is a letter to his then-teenage son about the feelings, symbolism, and realities associated with being Black in the United States. There, he shares an important reminder:

But all our phrasing—race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy—serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this. You must always remember that the sociology, the history, the economics, the graphs, the charts, the regressions all land, with great violence, upon the body (Coates 2015).

(Optional: Watch the 2:21-minute trailer to the film Between the World and Me [Streaming Video] to hear more quotes from that letter.)

A devastating example of violence upon the body is the disproportionate use of force that police officers use against young Black males in the United States. An individual police officer may have prejudicial beliefs that Black people are more likely to be violent than white people. Based on this prejudice, the officer may be more likely to racially discriminate against Black people and more likely to use more physical force against Black people than against white people. What do we call it, though, when this kind of discrimination happens repeatedly?

The Mapping Police Violence organization reports that year after year, police continue to disproportionately kill Black people in the United States. In 2023, Black people were more likely to be killed by police, more likely to be unarmed, and less likely to be threatening someone when killed. These disparities cannot be explained by individual acts of discrimination alone. Instead, it makes sense to argue that racial discrimination has become institutionalized in our law enforcement systems.

Looking beyond the institutionalization of law enforcement, we can see that laws are written in ways that discriminate against Black people. The disparities in sentences for possession of crack and possession of cocaine are one example (Crow and Johnson 2008). Black people are more likely to receive harsher sentences for crimes they have been accused of committing (Gottschalk 2015). When we look at these systems together, we can see that racial discrimination is consistent and systematic and crosses institutions. Because it is woven into the fabric of our history, culture, and ideology through white supremacy, we can say that this racism is structural.

Norms, Gender, and Sexual Orientation

Oppression around gender and sexual orientation can be as devastating as racism. One in three women over the age of 15 worldwide has faced a form of physical and sexual violence from their intimate partners, from their non-partner, or both, at least once in their life. And because much violence against women goes unreported, the actual figures are believed to be much higher. The stigma and shame associated with reporting and the lack of investigation and convictions discourage victims from reporting (World Health Organization 2024).

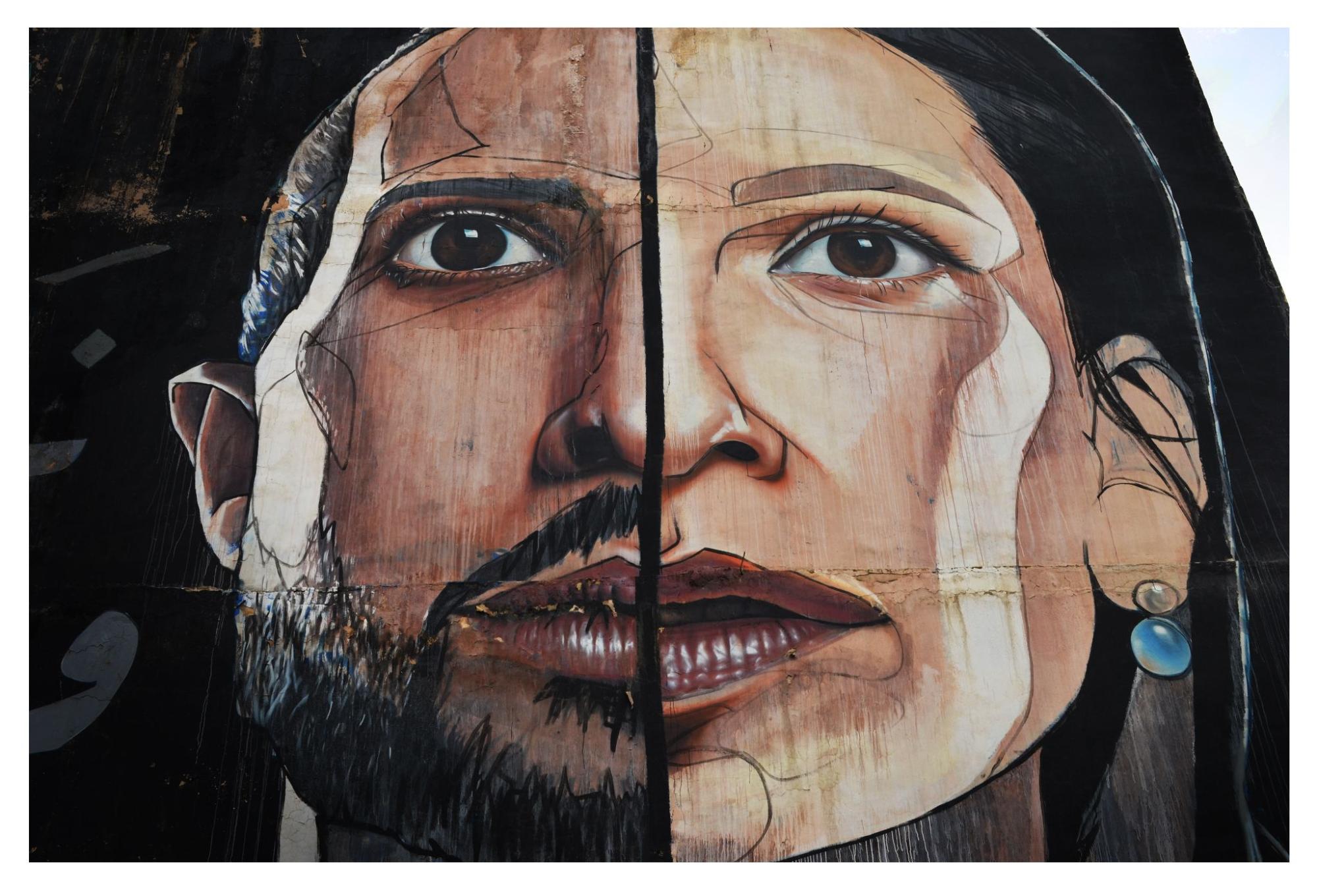

In addition to violence, women and girls are faced with multiple and intersecting discriminations and restrictions by people in power (of all genders). These are often fueled by pervasive and damaging gender stereotypes. Women and girls experience limited access to education and the ability to earn income. All this limits their economic power and puts restrictions on their ability to participate in debates and political processes (figure 3.18). These discriminations and restrictions deny them their full enjoyment of fundamental human rights (ARTICLE 19 n.d.).

LGBTQIA+ people worldwide, like women and girls, experience multiple intersecting forms of discrimination and harm by people in more powerful roles. Discriminations might be made by lawmakers and lobbyists who create structural barriers to equal participation in civil and political life. These discriminations are often based on harmful gender norms, the collectively held expectations and beliefs about how women, men, girls, and boys should behave and interact. One example of a gender norm is the expectation that there are only two genders, man and woman, and that we all should belong to one or the other. Harmful norms might be created and perpetuated by leaders in institutions such as education and religion.

Some transgender people may feel pressure to conform to gender norms. Due to societal pressure, many transgender individuals may feel compelled to suppress or hide their identity. Most children have a limited understanding of the social and societal implications of being transgender, but they can strongly feel misaligned with their assigned sex. Given that many transgender people do not come out or begin transitioning until their 20s or later, they may live with this distress for a long time.

In addition to potential conformity pressures, queer youth experience bullying and harassment in school that threaten their sense of safety and potential for success. This lack of safety is particularly pronounced when we take an intersectional lens. Nationwide, schools are hostile environments for LGBTQIA+ and gender-nonconforming students. But the impact is amplified for LGBTQIA+ youth of color, as they may be bullied based on their race, sexual orientation, and gender identity at once (The 2021 National School Climate Survey 2022).

These youth may have limited social supports to help them navigate the hostile environments they encounter regularly. In a study of queer youth who identified as Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black, researchers found a disproportionately higher experience of suicidal ideation (Lardier 2020). In this study, the combination of limited social support and school bullying amplified the effect of suicidal ideation for queer youth of color. The intersectional nature of gender identity and ethnic/racial identity plays a role in creating such devastating experiences for youth.

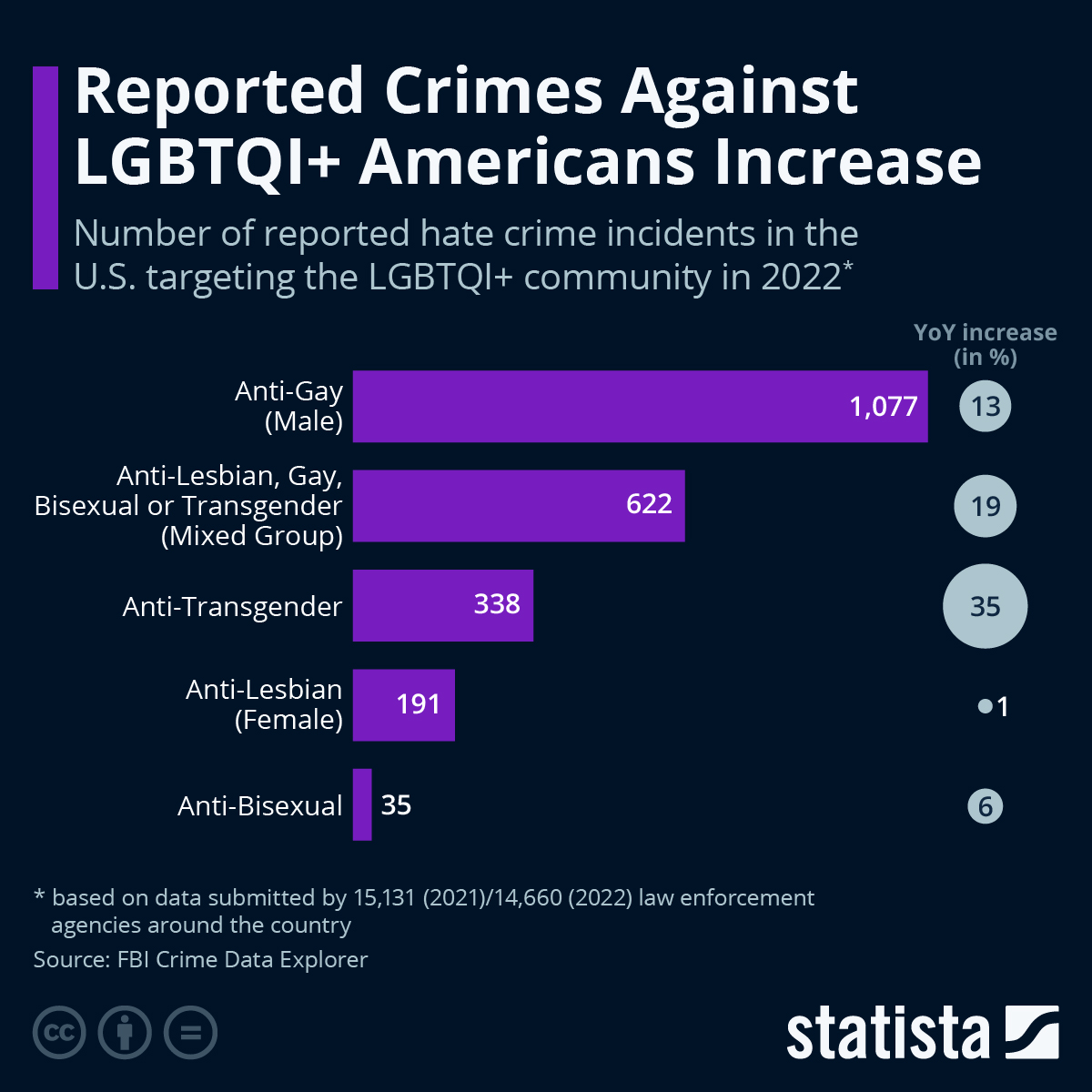

Harm can go beyond bullying and harassment for LGBTQIA+ people. In the United States between 2017 and 2019, the odds of being a victim of a violent hate crime for LGBTQIA+ people were nine times greater than it was for cisgender and straight people (Truman and Morgan 2022). While the acceptance of equal rights for queer people seems to be at an all-time high (GLAAD 2023), hate crimes against LGBTQIA+ people have increased across the board (figure 3.19). An increase in crimes relating to transgender bias was especially pronounced (Zandt 2024). Since these numbers only cover the incidents where the victim reported the crime, the real number of cases is likely significantly higher.

This section has only introduced a few examples of how systems of oppression impact groups in society. What is common to all is that power creates inequity, and intersectionality compounds experiences of oppression and privilege. For people of color, white dominant culture and white supremacy contribute to institutional and structural racism. For members of the various LGBTQIA+ communities, the process of normalization plays a powerful role.

Going Deeper

To learn more about white supremacy, see the handout “White Supremacy Culture” [PDF].

To see more about hate groups in the United States, view the Southern Poverty Law Center’s map section [Website]. You can filter by “Ideology.”

For more information on how power and whiteness play a role in our interactions, see the PBS site Race: The Power of an Illusion [Website]. Go to the “Themes” tab and find the articles “Racial Classification: Who Decides?” and “Making Whiteness” (figure 3.20).

To read more about bullying and harassment experienced by LGBTQIA+ people, read the report “Bullying and Suicide Risk among LGBTQ Youth” [Website].For more information via infographics on safety and rights for members of LGBTQIA+ communities, see the bottom of this Statista page [Website].

The 3:41-minute video “Power Privilege and Oppression” [Streaming Video] brings together most of the concepts we’ve explored here.

Licenses and Attributions for Systems of Oppression

Open Content, Original

“Systems of Oppression” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The first paragraph of “Power, Inequality, and Inequity” is adapted from “Conceptualizing Structures of Power” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.13. Wheel of Power and Privilege is designed by Kimberly Puttman, Michaela Willi Hooper and Lauren Anstrosiglio, based on the work of Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberlé

Crenshaw and Allan Johnson, with Syvia Duckworth (images) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (images). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.16. Image of Toni Morrison (left) on Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. Mural of Toni Morrison (right) on Flickr by Elvert Barnes is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 3.17. Image of Ta-Nehisi Coates (left) on Flickr by 92YTribeca is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 3.18. Gender equality mural in Jordan: divided but equal on Flickr by Mary Crandall is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 3.19. 2022 data report of hate crimes against LGBTQIA+ individuals by Statista is licensed under CC BY-ND 3.0.

The definition of intersectionality in the second paragraph of “Intersectionality” is adapted from “2.6 Social Theory Today” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Paragraph two of the introduction (definition of oppression) is derived from the “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Glossary” at the College of the Environment, University of Washington website and included under fair use.

Figure 3.12 is a screenshot of the video, “Systemic Oppression & Systemic Racism 101” by Unified Causes licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.14. “Kimberlé Crenshaw at Ted + Animation” by Kate Andersen is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.15. Southern Poverty Law Center’s map of General Hate groups is included under fair use.

Figure 3.17. Screenshot from video trailer to Ta-Nehisi Coates’s film, “Between the World and Me” by Stream Source Trailers (right) is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.20. Images of articles from Race: The Power of an Illusion included under fair use.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the idea that inequalities produced by multiple and interconnected social characteristics can influence the life of an individual or group. This suggests that we should view gender, race, class, or sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

transformations in human interactions and relationships that transform cultural and social institutions.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

the belief, theory, or doctrine that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups, and are therefore rightfully the dominant group in any society.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the system of racial bias that exists across institutions and society.

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.

preconceived beliefs, attitudes, and expectations about racial group members.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

a process that constructs specific behaviors, presentations, and ideas as the idealized norm through correction.