6.6 New Economic Models

The capitalist economic system also has profound effects on the living systems of the world. As we live in a period of cascading ecological crises, from mass extinction (Kolbert 2016) to climate disasters, many scholars have asked how we should understand this moment. An increasingly popular answer is to call this period the “Anthropocene.” The Anthropocene is a name given to the most recent geological epoch of time, beginning around the Industrial Revolution, in which humans have fundamentally transformed the living systems of the Earth.

Since the prefix “anthro” refers to humans, the name “anthropocene” identifies “humans” as the root cause of these global transformations. And yet, most humans, for most of human history, have not reordered the world in the way that we currently see. Some scholars, like the economist Raj Patel and the sociologist Jason Moore, argue that it is misleading to place the devastation caused by our current society at the feet of “humanity.” Rather than humanity itself, they argue that the root cause of these ecological crises is actually the capitalist economic system. They propose a new name for this epoch: the Capitalocene—the geological epoch in which capitalism has reordered Earth’s systems (Patel and Moore 2018).

To consider some of the ways our economic system relates to the ecological crisis, listen to the second chapter of Ben’s podcast Tracing the Roots of the Climate Crisis, “Chapter 2: Capitalism” (figure 6.17). It is 13 minutes long. In this episode, Ben explores the question: Is the climate crisis, and the ecological crisis more broadly, the predictable outcome of a certain economic order? Who is it designed to serve? Is it compatible with a thriving and just community and a survivable future? How do we dismantle such a dangerous system and build an economy that attends to the needs of human and nonhuman communities?

As Ben raises in the podcast, it’s crucial that we ask questions about any predictable outcomes that our economic order creates toward our ecological crisis. There is growing awareness that conventional economic models do not provide the necessary solutions to the challenges we are facing.

We need to find new systems that can better address poverty, inequality, our financial crises, and climate change. These new systems must allow us to better engage with each other and the natural world. In response to this, alternative economic models are emerging. They are based upon placing real human and environmental needs at the forefront, and they honor diverse social values instead of just monetary ones. Let’s look at a few.

Re-Evaluating Growth

Foundational to the new economic models we’ll discuss in this section is the perspective that economic growth needs to be re-evaluated. Economic growth is an inherent trait of the capitalist model. It requires ever-increasing production and consumption. Professor and author Susan Goldsworthy states that we are “obsessed by growth; it’s how we measure the success of organizations and of countries. And yet, it’s this very obsession that is accelerating our own demise” (Goldsworthy 2022).

This re-evaluation of growth is not new. In Europe, in the late 1960s and 1970s, scholars debated the value of aiming for economic growth, an inherent part of our capitalist system. It wasn’t until 2002 that we saw protests related to concepts of degrowth (Duverger 2020). Proponents at the heart of this movement acknowledge that endless growth is not possible on a planet with finite resources. Growth is also seen as a phenomenon that promotes competition versus collaboration between people and prioritizes profits over people (Goldsworthy 2022).

Several initiatives sprung out of this movement. For example, voluntary simplicity is a lifestyle choice that minimizes the needless consumption of material goods and the pursuit of wealth for its own sake (figure 6.18). Another example is neo-ruralism, the practice of migrants moving from cities to rural areas to live an agrarian lifestyle as a means of reducing consumerism and transforming market relations, values, and practices (Duverger 2020).

Localization

Localization is one of the movements that influence and shape new economic policies. Localization is a process of decentralization that shifts economic activity into the hands of millions of small- and medium-sized businesses instead of concentrating it in mega-corporations. Proponents of localization imagine a world where food comes from nearby farmers who ensure food security year-round and money we spend on everyday goods continues to recirculate in the local economy. Local businesses are able to provide enough meaningful employment opportunities for residents.

Localization is the basis from which new economic structures can evolve. As they do, they allow the goods and services a community needs to be produced locally and regionally whenever possible. Instead of communities depending on distant, unaccountable corporations, they are able to be self-reliant. Localization is not imagined as total isolation. Products from surplus production are exported by communities once local needs are met, and goods that can’t be produced locally are imported. The free exchange of knowledge and ideas are still encouraged across borders, and global problems like climate change are still addressed globally.

The Economics of Happiness

A few nations have adopted economic policies that pay attention to the holistic needs of societies, such as the Human Development Index and the Genuine Progress Indicator we discussed in Chapter 4. For example, the United Kingdom and New Zealand have incorporated well-being goals into their priorities for assessing their nations’ economic health. The government of Bhutan prioritizes the philosophy of gross national happiness.

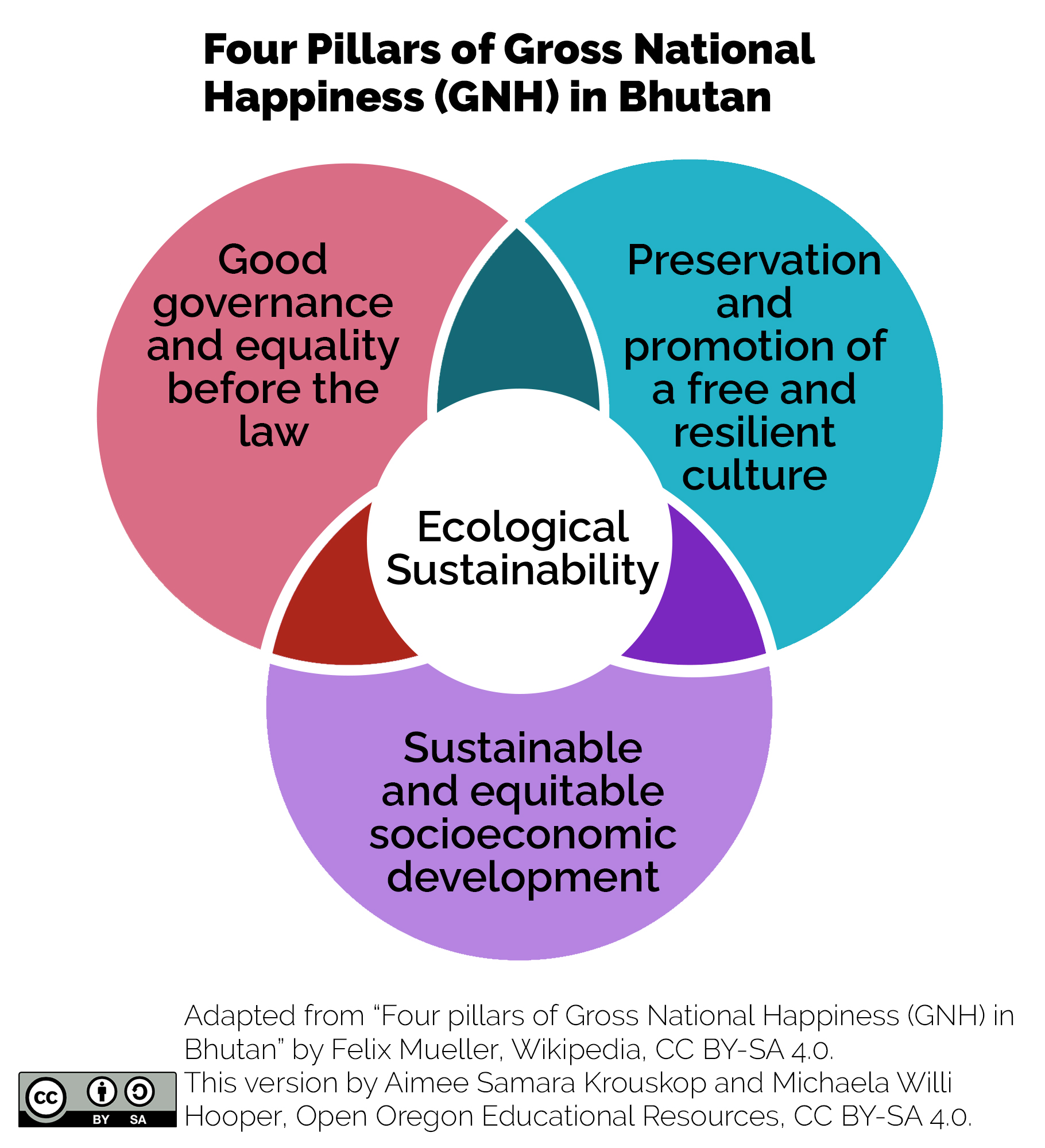

Gross national happiness (GNH) includes an index that is used to measure the collective happiness and well-being of a population. The index has four pillars: Preservation and Promotion of Culture, Sustainable and Equitable Social and Economic Development, Conservation of Environment, and Good Governance and Equality Before the Law (figure 6.19).

Within each of those pillars are indicators of well-being that planners and policy makers can study. For example, the Preservation and Promotion of Culture is in part measured by how many residents speak their native language. Sustainable and Equitable Social and Economic Development is, in part, measured by how many healthy days residents have in a year. Among other calculations, the Conservation of the Environment is measured by the level of responsibility that people take in caring for the environment.

Watch this 3:29-minute video, “What is ‘Gross National Happiness’?” [Streaming Video] (figure 6.20). As you watch, what comparisons can you make between the dominant economic system most of us live with and the system established with GNH priorities?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Zqdqa4YNvI

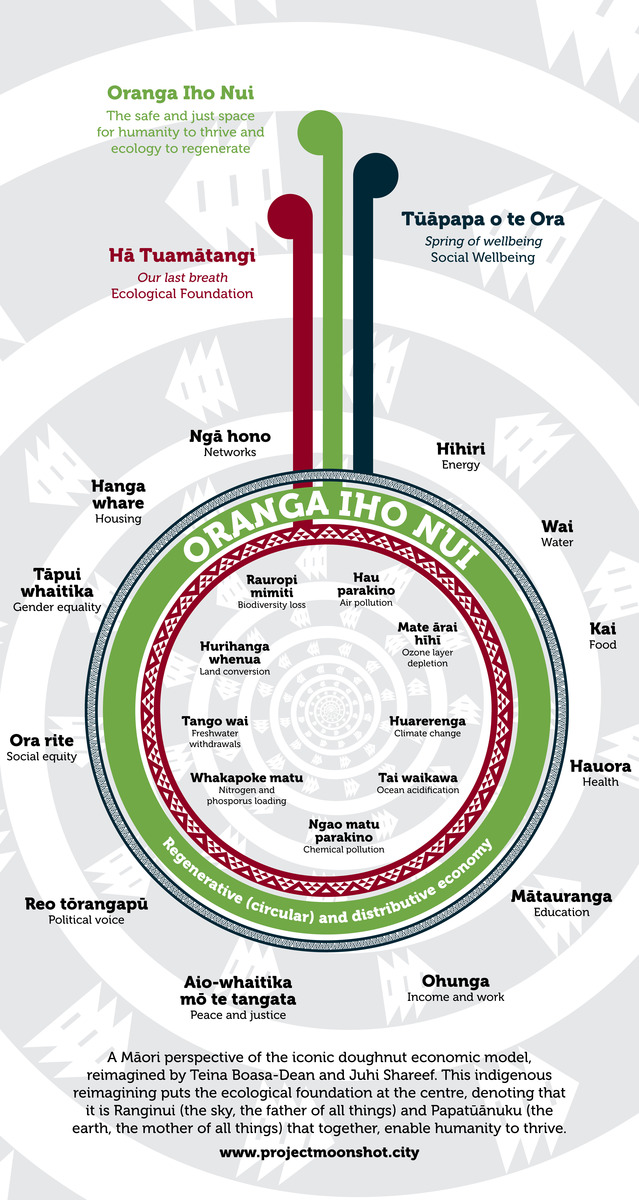

Doughnut Economics and Māori Worldview

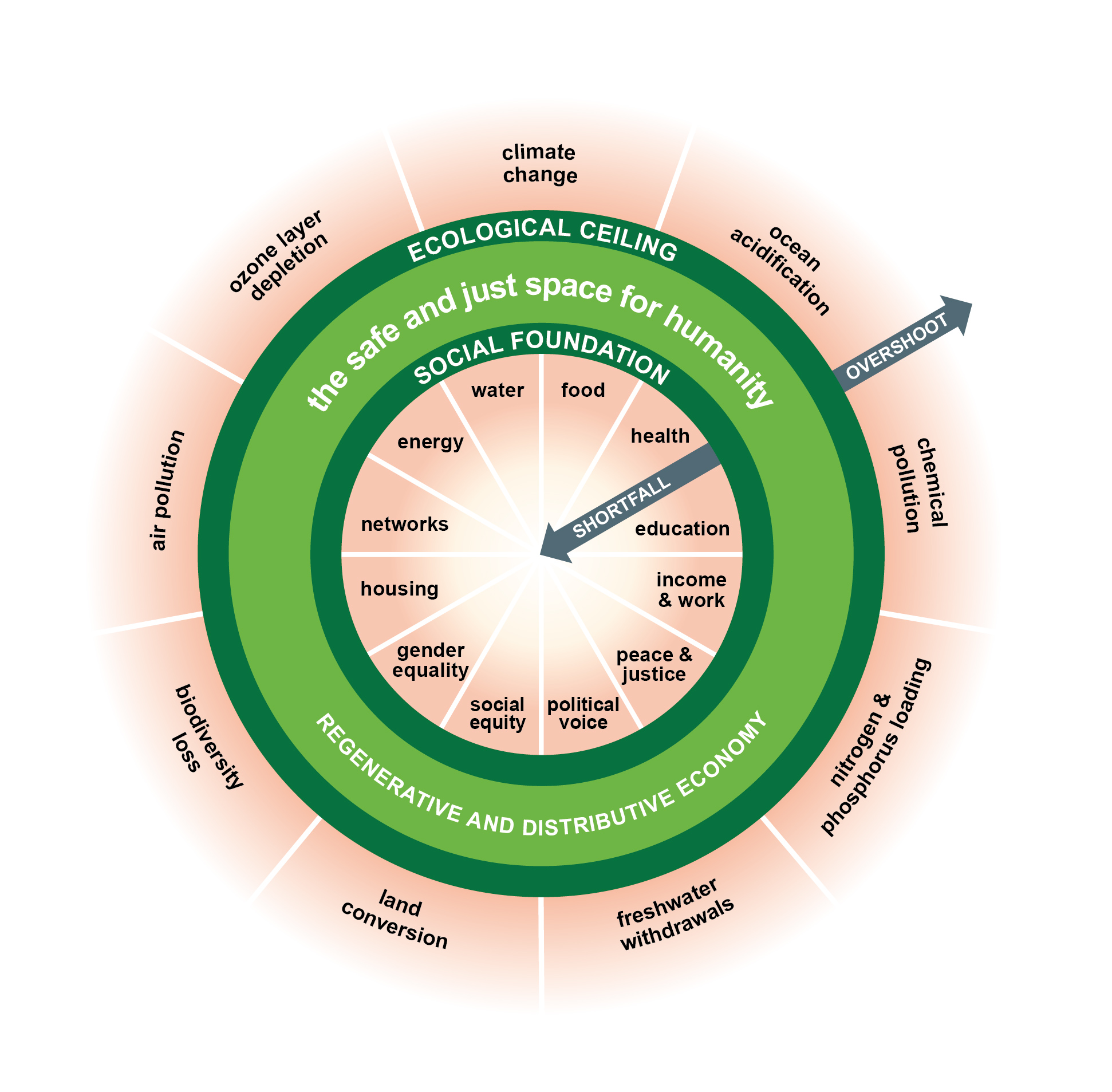

Another alternative way of structuring our economic systems is with Doughnut Economics, an economic model that balances essential human needs with planetary boundaries (figure 6.21). First published in 2012 by economist Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics provides an alternative to the goal of gross domestic product (GDP). It is also based on the principles of re-evaluating growth. It is a way to acknowledge real human and ecological needs in our economic systems. Key to this model is a visual depiction with two concentric rings: a social foundation and an ecological ceiling.

The social foundation is framed to ensure that everyone receives life’s essentials. The ecological ceiling is designed to prevent humanity from using Earth’s life-supporting systems beyond healthy boundaries. The target spot for achieving this balance is in a doughnut-shaped space that sits between the two. The idea is that if a society can be managed within that doughnut space, it will be both ecologically safe and socially just (Doughnut Economics Action Lab n.d.).

Figure 6.21 shows the visual framework of Doughnut Economics. Note how this model acknowledges that economies, societies, and the natural world exist as complex, interdependent systems. Watch the 6:30-minute video “How the Dutch Are Reshaping Their Post-Pandemic Economy” [Streaming Video] (figure 6.22). It is narrated by the originator of the Doughnut Economics concept, Kate Raworth. The video explains how the doughnut is applied and how planners in the city of Amsterdam have committed to using it as a model. Can you imagine applying the doughnut to a place where you live? What would that look like?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ziw-wK03TSw

A crucial element in any organizational model for societies is that it is designed with the perspectives and worldviews of those who reside within that society. For example, sustainability professional Juhi Shareef is an adopter of the Doughnut Economics model. When she moved to New Zealand, she recognized the need to partner with the Indigenous people of that area to make the model truly useful. She explains:

Working in sustainability, one understands that context is key. When we fail to identify or understand the nuanced, complex, systemic and local context of a situation, the best-intentioned solutions simply won’t solve society’s most pressing problems (Shareef 2020).

Shareef reached out to Teina Boasa-Dean, a member of the Tūhoe Māori iwi (“tribe” in Māori). Shareef asked her to help in understanding how the Doughnut Economics model could be adapted to better reflect the worldview of the more than 775,000 Māori people who live in New Zealand. Teina Boasa-Dean is an environmental scientist who works with both a technical perspective of the Tūhoe and an understanding of Western science (Shareef 2020).

Take a look at the way that Boasa-Dean reimagined the doughnut in figure 6.23. How does it differ from the original doughnut in figure 6.21?

It is important to remember that Boasa-Dean is a member of only one iwi, and over a hundred iwis reside in New Zealand, each with unique cultural expressions. Thus, she can only speak to the cultural perspectives of the Tūhoe Māori. However, what she shares can serve to help us better understand communities that place nature at the center of existence.

What is most pronounced about Boasa-Dean’s interpretation is that the environment sits in the middle of the doughnut as its foundation. Social elements sit in the outer ring. This reflects Boasa-Dean’s perspective that humans are dependent on the biosphere, not the other way around (Shareef 2020). Boasa-Dean spoke more about this perspective in a speech at the Circular Economy Pacific Summit in 2019:

…My own experiences of the land, the waterways, the winds, the sun, the moon and the stars have been guided and enhanced by the cosmological and pragmatic teachings of my elders. In turn their insights had been nurtured over thousands of years. I have been nurtured by these elders to understand a deep respect for mother nature and the myriad of rituals and [they have] affirmed and reaffirmed my relationship.

I have been taught to leave offerings at the entranceway of forests of the mountain ranges and rivers and at ocean landmarks. I have also been taught to leave a new offering when I exit these natural paradises and each offering is couched inside a brief but relevant karakia or thanksgiving prayer. The offerings were often leaves or stones infused with prayer. It is a whole living system whether we know it or not. We are constantly re-humanized by this divine bond with nature and this is the relationship that was most valuable to my elders (Boasa-Dean 2019).

Teina Boasa-Dean’s perspective adds a crucial perspective to the Doughnut Economics model, as well as other new models in development: that economic systems should serve “the management of people for the benefit of Whenua [Earth], not the reverse” (Boasa-Dean 2019).

Going Deeper

To better understand how economic growth is being reconsidered, watch the documentary “Sustainable Business, Rethinking Growth” [Streaming Video], produced by DW Documentary.

For more on Bhutan’s economics of happiness, watch this 6:23-minute video, “Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness” [Streaming Video], or this 19:15 video, “The Economics of Happiness (Abridged Version)” [Streaming Video], a short version of a film by the organization Local Futures.

For more on Doughnut Economics and the re-evaluation of growth, watch this 15:53 minute TED Talk video, “A Healthy Economy Should Be Designed to Thrive, Not Grow” [Streaming Video].

To hear more about Teina Boasa-Dean’s perspective on Doughnut Economics based on the Tūhoe Māori worldview, listen to the 22:50-minute podcast “Episode 2 – Teina Boasa-Dean and a Maori Interpretation of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics” [Streaming Audio].

Licenses and Attributions for New Economic Models

Open Content, Original

“New Economic Models” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.17. Tracing the Roots of the Climate Crisis, “Chapter 2: Capitalism” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.18. “Banksy black Friday” is on Flickr by John Jones and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 6.19. “Four Pillars of Gross National Happiness (GNH) in Bhutan” is adapted from “The Four Pillars of Gross National Happiness in Bhutan” by Felix Mueller, Wikipedia, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications: More accessible design by Aimee Samara Krouskop and Michaela Willi Hooper, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 6.21. “Doughnut Economics Model” is on Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 6.23. “A Tūhoe Māori Perspective of the Doughnut Economics Model Reimagined by Teina Boasa-Dean” by Doughnut Economics Action Lab is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.20. “What Is Gross National Happiness?” by mallorcamorten is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 6.22. “How the Dutch Are Reshaping Their Post-Pandemic Economy” by BBC Global is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the most recent geological epoch of time, beginning around the industrial revolution, in which humans have fundamentally transformed the living systems of the Earth.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

a process of decentralization—shifting economic activity into the hands of millions of small and medium-sized businesses instead of concentrating it in mega-corporations.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

an economic model that balances essential human needs with planetary boundaries.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.