9.4 Foundational Perspectives on Religion

Sociologists explain how religion influences social change using different perspectives. While the shape and label of sociology did not develop until the 19th century, there were earlier thinkers that spoke and wrote extensively about sociological ideas.

Social phenomena were dominant topics in ancient Greece. The guidance developed by Confucius to achieve a harmonious society became prominent in China around 260 BCE (Tseng et al. 1985). Tunisian-born Ibn Khaldun became a prominent Muslim scholar during the 14th century. Some consider Khaldun to be the father of sociology, as he presented some of the earliest known theories of social cohesion and social conflict (Mendoza et al. 2023). The term “sociology” was first introduced in the 1700s, and foundational theories of the discipline were developed in the 1800s.

As we explore all these foundational ideas, keep in mind that each contributor framed their perspective within the specific historical and cultural realities that existed during their lives. For example, Khaldun’s writings were influenced by his Islamic faith and the political and religious turmoil of his Mediterranean homeland during Islam’s Golden Age. Durkheim’s major works were influenced by a politically stable period in France in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This allowed him to focus on what creates that stability and on policy issues. On the other hand, Marx was influenced by a youth spent during the tumultuous first half of the 19th century and an adulthood that witnessed a rapidly industrializing Europe.

As we introduced in Chapter 3, the foundational theories of sociology include functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. This section will examine how sociologists view religion’s role through those perspectives.

Religion as Symbolic Interaction

Symbolic interactionism examines how society is created and maintained through face-to-face, repeated, meaningful interactions. This perspective arises from the concept that our world is socially constructed. So, in the context of religion and spiritual belief systems, beliefs and experiences are not sacred unless members of a society agree to regard them as sacred. Interactionists also recognize that religious and spiritual traditions use many physical and nonphysical symbols to help us construct meaning, come to these agreements through interaction, and cohere a community around a specific set of beliefs.

For example, researchers studying religion in Croatia argue that celebrating religious feast days, while using iconic religious symbols, connects people in a common religious membership (Kovačević et al. 2021). One feast day that brings Catholics together is the feast of Our Lady of Sinj. Our Lady of Sinj is the title of a painting venerated as miraculous of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The sanctuary in Sinj, where the painting is located, is a pilgrimage site (figure 9.6).

A scholar using the interactionist approach might ask questions about the interactions between religious leaders and practitioners. They might study how religion and spiritual belief systems influence our daily decision-making or the ways people express their belief-based values to others.

Also core to the interactionist perspective is how individuals identify themselves within groups. Some sociologists will focus on how people categorize their religious or spiritual identity and count the people who belong to or ascribe to those beliefs. This allows them to track membership or affiliation over time, providing insights into how the world is changing.

In one approach to categorization, the Pew Research Center measured the religious affiliations of people in 2010 and predicted what they would look like in 2050 (figure 9.7). The researchers named Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Judaism as major worldwide religious traditions. People practicing these world religions in 2010 included approximately 77 percent of all the people worldwide.

Stability, Solidarity, and Integration

French social theorist Émile Durkheim (figure 9.8 [left and right]) defined religion as a “unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things.” To him, “sacred” meant “extraordinary”—something that inspired wonder and connected to the divine. Durkheim argued that we create separations between ordinary life, the profane, and spiritual life, the sacred. A rock, for example, isn’t sacred or profane as it exists. But if someone makes it into a headstone, or another person uses it for landscaping, it takes on different meanings—one sacred, one profane. Durkheim also identified ways that religion serves society, building a functionalist view of religion.

Functionalism examines religion’s contribution to social stability through solidarity and social integration. This perspective focuses on four main ways that religion serves society. First, religion gives meaning and purpose to life. Many things in life and death remain a mystery, especially for societies that rely on Western scientific knowledge. Religious faith and belief help many people make sense of phenomena that science cannot explain. Often, members of religious organizations talk about the way that faith in a higher power provides meaning in their lives. The kind of meaning that faith provides might be associated with how they relate to others (such as parenting), their professional calling, what happens after death, or their individual experience with a higher power.

A second function of religion is greater psychological and physical well-being. Religious faith and practice can enhance psychological well-being. It can be a source of comfort to people in times of distress by enhancing their social interaction with others. Many studies find that people of all ages, not just the elderly, are happier and more satisfied with their lives if they are religious. Religiosity also apparently promotes better physical health. Some studies even find that religious people tend to live longer than those who are not religious (Moberg 2008).

Third, religion reinforces social unity and stability. This was one of Durkheim’s most important insights. Religion strengthens social unity and stability in at least two ways. It gives people a common set of beliefs and thus is an important agent of socialization (explored in Chapter 2). Also, the communal practice of religion brings people together physically, facilitates their communication and other social interactions, and thus strengthens their social bonds. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, congregants came together virtually to celebrate community.

A fourth function of religion is the implementation of social control and social order. Social control is a way to formally and informally regulate, enforce, and encourage conformity to norms. Religion teaches people moral behavior and thus helps them learn how to be good members of society. In Christianity, for example, the Golden Rule is “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Many religions share this rule, written in alignment with their own cultures, as shown in figure 9.9.

Unity, Stability, and Religious Change

How do the functions of religion relate to social change? Durkheim believed that people prefer to maintain the outcomes of religion he outlined: social control, amplified meaning, interrelatedness, and unity. Thus, religion prevents social change as members will choose to follow and expect the social norms and values that serve these functions. Social scientists Bronisław Malinowski and Talcott Parsons also supported the idea that religion reinforces social norms and stimulates social solidarity. To them, this creates more stability in society than change.

Religion can be a source of two kinds of stability. Sometimes that stability is positive, creating connection and continuity for groups. Other times, religion’s resistance to change preserves harmful practices of discrimination and oppression. While religious systems are very complex, it can be said broadly that many world religions vary from fundamentalist to progressive beliefs.

Judaism, for example, varies from ultra-Orthodox (called Haredi Judaism) to Reform denominations. Christianity varies from Catholicism to United and Metropolitan community churches, and Islam also varies between Shia and Sunni adherents. Fundamentalism is a religious movement that requires a strict and typically literal interpretation of core texts and adherence to traditional beliefs, doctrines, and rituals. This orientation emphasizes social control.

As a vehicle of that social control, fundamentalist forms of religious traditions insist that members comply in detail with their related holiness code, a set of core laws or principles that define the key ideas for that organization. In the United States, we see Christian fundamentalism related to views such as abortion. Hindu fundamentalists support a philosophy in India that includes the outlawing of beef consumption. Muslim fundamentalists insist on strict interpretations of the Qur’an, perhaps most visible in interpretations of the role of women.

Many fundamentalist believers view homosexuality as a sin as part of their holiness code. Further, they argue that same-sex relationships violate the God-given order. Sometimes religious people further on the fundamentalist spectrum will implement social control over gender and sexuality, using shunning and derogatory words. In one study, the researcher found that some fundamentalist church members called LGBTQIA+ people sinful, broken, and confused. LGBTQIA+ church members were threatened by eternal damnation (Hollier et al. 2022).

On the far end of fundamentalism is religious extremism. Extremism can look like vocal or active opposition to religious tolerance. It can also be a system that tries to manage religious social control through the political system, such as criminalizing abortions in the United States. Sometimes extremism legitimizes violence as a tactic of social control. Violence against women can be allowed and encouraged when they don’t follow the rules (Derichs and Fleschenberg 2010:21). In the United States, we are seeing an increase in hate crimes by white Christian extremists against South Asians, in part because they are targeted as Muslim, even if they are from a completely different faith system (Dirks 2022).

Media accounts sometimes use the words religious fundamentalism, extremism, and terrorism incorrectly, as if the words are interchangeable. For example, you may have heard that Islamic fundamentalists were responsible for the bombing of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. However, these bombers were not just fundamentalists; they were violent extremists. People can be fundamentalist in their beliefs without being violent.

Another example of extreme religious social control is conversion therapy. In this “therapy,” people who are gay are subjected to physical and mental torture in an attempt to change their sexual orientation (Bradfield 2021) (figure 9.10). Only some people from fundamentalist religions would agree with conversion therapy. However, this example of social control is rooted in extremist fundamentalist beliefs.

Opposing Ideas on Conflict

We introduced Karl Marx in Chapters 3, 5, and 6, and Max Weber in Chapters 4 and 6. They were 19th-century sociologists who studied religion in the context of conflict and change. As conflict theorists, they focused on patterns of social inequality that religion fosters. They each emphasized the relationship between religion and society’s economic and social structure.

Max Weber believed religion could be a force for social change. As we discussed in Chapter 6, Max Weber (figure 9.11) argued that the shift from an agrarian to a capitalist economy in Western Europe was supported in part by a particular kind of religious belief. This variation of Protestantism encouraged making money by motivating believers to work hard, be successful, and not spend their profits on frivolous things. Success in the world became a sign of God’s favor. He pointed out that heavily Protestant societies—such as those in the Netherlands, England, Scotland, and Germany—held the most highly developed capitalism as their economic structures. As Protestantism became the religion of the dominant social class, it drove economic and social change.

Karl Marx (figure 9.12) viewed religion as a tool used by capitalist societies to perpetuate inequality. He believed religion reflects the social stratification of society. The religion of the dominant class maintains inequality and perpetuates the status quo. For him, religion was just an extension of working-class (proletariat) economic suffering. He famously argued that religion “is the opium of the people.” By focusing on rewards in the afterlife, religion was a drug that served to numb people to their suffering here on earth.

Like Durkheim, Marx argued that the dominant religion in a society maintains social stability and resists social change. Unlike Durkheim, he focused on how religion helped wealthy capitalists (the owners of the means of production) maintain their power. By using theology that claimed that social inequality was part of the divine plan, capitalists could maintain an impoverished labor force. They would proselytize that in “God’s will,” some people would always be poor. In this sense, religion is a force for economic and social stability.

Modern conflict theorists also point out that those in power often dictate religious beliefs and practices through their interpretation of religious texts or via proclaimed direct communication from the divine. People in the dominant class use religion to enforce their social control. Because people in power want to retain their power, they emphasize religious practices that resist social change.

Going Deeper

In addition to the categories listed in figure 9.7, the researchers at Pew also categorize people into the category “folk religions.” This category includes traditions such as Chinese folk religions, African folk religions, and other Indigenous folk religions. However, many people who practice these traditions wouldn’t consider them religions (King 2013).

The category “Other Religions” is “an umbrella category that includes Baha’is, Jains, Sikhs, Taoists, and many smaller faiths” (Pew Research Center 2015:8). The categories “folk religions” and “other religions” hide more diversity than they reveal. They also reflect the power of dominant world religions, minimizing the unique worldviews, beliefs, and practices of many other spiritual traditions.

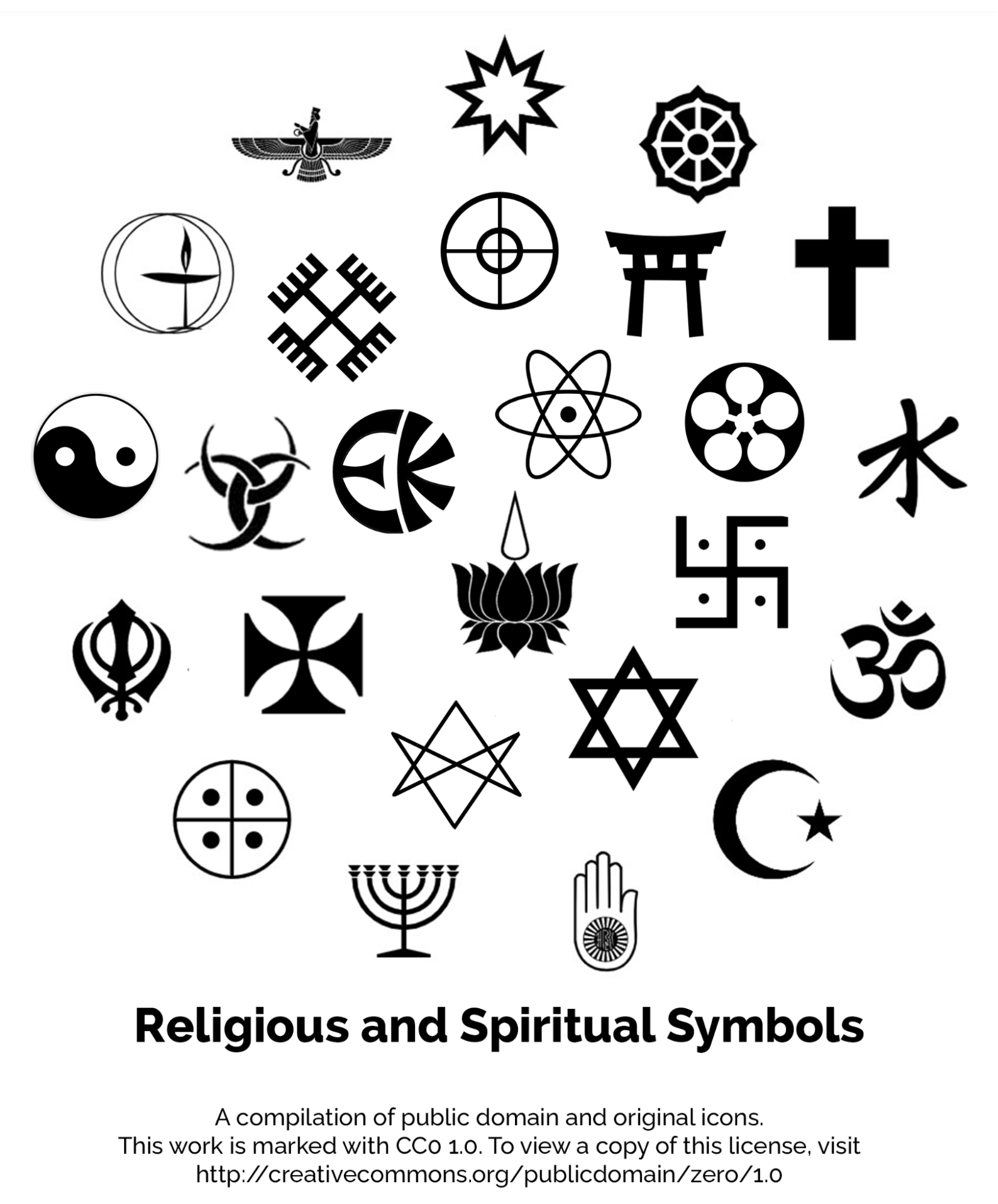

Even though spiritual belief systems are universal, there is vast diversity among religious and spiritual beliefs. Review the infographic of religious and spiritual symbols presented in figure 9.13. The Star of David represents Judaism. The cross symbolizes Christianity. The crescent and star icon represents Islam. Intersecting lines through two circles symbolize the Isese spirituality of the Yoruba people (a West African ethnic group, mainly residing in Nigeria, Benin, and Togo).

Interactionists are interested in the shared meaning these kinds of symbols hold. In what ways can you imagine that interactionists study this diversity in the context of social change?

Licenses and Attributions for Foundational Perspectives on Religion

Open Content, Original

“Foundational Perspectives on Religion” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.13. “Religious and Spiritual Symbols” compiled by Kimberly Puttman and Michaela Willi Hooper is in the public domain, CC0 1.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Religion as Symbolic Interaction” is adapted significantly from “Symbolic Interactionism” in “The Sociological Approach to Religion” in Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Social Control” and “Fundamentalism” definitions from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Stability, Solidarity, and Integration” is a adapted from “The Functions of Religion” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by University of Minnesota Libraries and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, and “About Religion” in World Religions: the Spirit Searching by Jody L. Ondich, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.8. “Photo of Émile Durkheim” by Ferdinand Tönnies is on Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (left). “Photo of Émile Durkheim Teaching a Course at the Sorbonne University in Paris” by Jean Bonnerot is published on Nubis and licensed under Etalab Open License (right).

Figure 9.10. “Photo Self Hatred Is Not Therapy” by Daniel Tobias is licensed under CC BY-SA-2.0.

“Opposing Ideas on Conflict” is adapted from “The Functions of Religion” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by University of Minnesota Libraries and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.12. “Photo of Karl Marx” is on Flickr, by Antonio Ponte and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (left). “Photo of Mural by Diego Rivera featuring Karl Marx” is on Wikimedia Commons, and licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.6. “Photo of Our Lady of Sinj Feast Day Procession” by Branko Čović is published by Total Croatia and included under fair use.

Figure 9.7. “Size and Protected Growth of Major Religious Groups” from “The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050” by Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2015), is licensed under the Center’s Terms of Use.

Figure 9.9. “The Golden Rule” by Paul McKenna, published on Scarboro Missions, is all rights reserved, and included with permission.

Figure 9.11. “Graffiti portrait of Max Weber at the Max-Weber-Schule in Freiburg, Germany.” is published on ThoughtCo and included under fair use.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the lifelong process of an individual or group learning the expected norms and customs of a group or society through social interaction.

a way to regulate, enforce, and encourage conformity to norms both formally and informally.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

A religious movement that requires a strict and typically literal interpretation of core texts and adherence to traditional beliefs, doctrines, and rituals.

a set of core laws or principles that define the key ideas for that organization.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.

the set of people who share similar social circumstances based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

the categorization of its people into rankings based on factors of power, access and resources, (such as wealth, income, education, or occupation) as well as social identities (like, race, ethnicity, or gender).

the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.