3.6 Classical Sociological Perspectives

As we have explored with earlier sections on social location and systems of oppression, we are not just individuals but also social beings deeply enmeshed in society. At the heart of sociology is the sociological perspective: the view that our social backgrounds influence our attitudes, behavior, and opportunities in life. While all sociologists would probably accept this basic premise, their views as sociologists differ in many other ways. Three early and foundational perspectives in sociology are structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. This section will examine how sociologists view society through those specific perspectives.

Structural Functionalism

Structural functionalism was the dominant theoretical framework in U.S. sociology from the 1940s into the 1960s and 1970s. This perspective tends to focus on macro-level phenomena and framed sociology’s understanding of the relationship between institutions. Functionalists proposed that because institutions work as interrelated parts of society, they create a stable social system. For example, common rituals and shared values help people feel connected to each other and create social cohesion (figure 3.29).

Talcott Parsons (1966) presented an equilibrium model of social change. He said that society is always in a natural state of equilibrium, defined as a state of equal balance among opposing forces. Gradual change is both necessary and desirable, typically stemming from factors such as population growth, technological advances, and interactions with other societies that introduce new ways of thinking and acting. However, any sudden social change disrupts this equilibrium. To prevent this from happening, other parts of society must make appropriate adjustments if one part of society sees too sudden a change.

Structural functionalism has been heavily criticized within more recent sociology. Some critics argue that functionalists present a static view of society that fails to account for the realities of social change. Others argue that there is a problem in assuming that everything that persists in society has a function for that society. For example, does poverty or discrimination really provide a function for society? The suggestion that institutions support stability is challenged because conflict can emerge when different institutions tell us to do different things.

Especially problematic is the way early structural functionalists likened change in society to change in biological organisms. They said that societies evolved just as organisms do, from tiny, simple forms to much larger and more complex structures. This framework has a limited understanding of earlier societies and their deep complexities.

Functionalism also struggles to explain inequality and, at its worst, may even help justify existing inequalities. For example, functionalist theory assumes that sudden social change is highly undesirable, when such change may in fact be needed to correct inequality and other deficiencies in the status quo. Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci claimed that the functionalist perspective justifies the status quo in society and the underlying power dynamics that maintain that status quo. Finally, other critics argue that functionalism discourages people from taking an active role in changing their social environment, even when doing so may benefit them.

Conflict Theory

First developed by Karl Marx in the 19th century, conflict theory also tends to focus on macro-level analysis of society. Conflict theory claims that society is in a state of perpetual conflict because of competition for limited resources. Social order is maintained by domination and power, rather than by consensus and conformity. However, tensions and conflicts arise under two conditions.

The first condition is when resources, status, and power are unevenly distributed between groups in society. The second is when members of a society with fewer resources, status, and power acknowledge that uneven distribution. Alongside that uneven distribution, they identify their social place in a stratified society. Because they focused on social class, early conflict theorists identified this as “class consciousness” (figure 3.30). But this awareness of social place also includes other social characteristics, such as race, gender, or religion. These two sources of conflict become the engine for social change.

Conflict theorists argue that the institutions of a society promote the interests of the powerful while subverting the interests of the powerless. Therefore, the status quo generally results in unequal societies. The conflict perspective thus views sudden social change in the form of protest or revolution as both desirable and necessary to reduce or eliminate inequality and to address other social ills. Throughout this chapter, we have presented ways that institutions create inequality and ways that institutions can help shift those realities. We’ll present many more examples throughout this textbook.

Conflict theory arose in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s against the backdrop of the rise of various social movements. Informed by these events, conflict theorists recognize that social change often stems from the agency of members of society. That is, change emerges from people organizing and mobilizing together to pressure the institutions of society. When efforts are combined by individuals, they create social movements to bring about fundamental changes in the social, economic, and political systems.

Critics of conflict theory argue that it exaggerates the extent of inequality and overemphasizes social change. It is also seen as centering social class in the analysis of the social world, rather than other sources of oppression and privilege, such as race and gender. We’ll explore more about conflict theory in the context of economy in Chapter 6 and of religion in Chapter 9.

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism grew out of the Chicago School of sociology, which is considered an epicenter of sociological thought between 1915 and 1935. Work at the Chicago School included field research and the first major studies of urban society. The sociologists at the Chicago School during this era influenced many of today’s well-known sociologists.

Unlike functionalism and conflict theory, symbolic interactionism provides a micro-level lens to understand society. It is the study of smaller-scale social interactions and actions and includes the social construction of reality perspective that we introduced in Chapter 2. Herbert Blumer, who coined the term “symbolic interactionism” in 1937, was a student of several sociologists at the Chicago School. He relayed that symbolic interactionism is concerned with how meanings are constructed through interactions with others. We attach meanings to situations, roles, relationships, and things whenever we encounter them. For a symbolic interaction to occur, these meanings have to be shared and agreed upon by the people you are interacting with.

For example, if we attach the meaning of “family member” to someone, we will treat them as a family member (or act on the basis of the meaning of family member). What we define as family originates from our interactions with others. We share common rituals such as holiday celebrations. We share common values such as kindness and loyalty. Through our interactions with our family, as well as with people outside our family (such as teachers, neighbors, or the media), we may come to modify our interpretations of what it means to be family.

From the symbolic interactionist perspective, social change is related to the shared meaning of symbols. For example, a symbolic interactionist studying the Black Lives Matter movement might try to understand what motivated individuals to join the protest or what meanings signs, chants, or hand signals have to participants (figure 3.31).

Symbols are also crucial in the formation of our social identities. In every waking moment, we are taking new impressions of the world around us. This means that symbols can take on different meanings to different individuals and that the meanings we attach to the world may change over time. Hence, there is no such thing as a static understanding of our shared meanings, or one’s identity and one’s place in the world. This is part of the social change process. When shared meanings decrease, groups of people become alienated and disconnected, which also leads to social change.

The meanings we assign to actions and people have real consequences for our lived experiences. For example, stereotypes and prejudice are socially constructed through interactions and shared meanings. When, as members of society, we act on our stereotypes and prejudices in the form of discrimination, we perpetuate inequalities by limiting opportunities and access to resources.

Symbolic interactionism also examines stigmatization: the labeling or spoiling of an identity, which leads to ostracism, marginalization, discrimination, and abuse. Returning to our Black Lives Matter example, it may be fair to say that anarchist symbols (clothes, slogans, icons) became more stigmatized during Black Lives Matter protests as people mistakenly associated all anarchists with protestors who were destroying property. We’ll mention more about anarchism in Chapter 6.

Critics argue that symbolic interactionism struggles to explain macro-level phenomena. Other critics argue that it tends to downplay power, privilege, and oppression. Some present-day interactionists have tried to correct these problems by showing how symbolic interactionism can be used to explain power (Athens 2010) and organizational patterns (Hallett and Ventresca 2006).

Instead of viewing common rituals and shared values as integrating people into the society, conflict theorists argue these values and rituals are actually ideologies that deceive people to make them comfortable with their position in society. One dominant ideology that is heavily criticized by conflict theorists is the idea of the “American Dream,” where you work hard and get ahead. Conflict theorists argue that the opportunities to get ahead for most people are severely curtailed due to barriers in most institutions. The American Dream ideology, according to conflict theorists, justifies the position of those already at the top of the power structure (Colomy 2010).

Erving Goffman (1922–1982), Howard Becker (1928–), Sheldon Stryker (1924–2016), Patricia (1952–), Peter Adler (1952–), and Gary Alan Fine (1950–) are some well-known interactionists.

Comparing and Applying Classical Sociological Perspectives

The classical theories in sociology present different perspectives and assumptions related to social change. Figures 3.32 and 3.33 summarize and compare the major assumptions of the functionalist and conflict approaches. Figure 3.32 shows the macrosociological perspective, and figure 3.33 shows the microsociological perspective.

| Theoretical Perspective | Major Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Structural functionalism | Society is in a natural state of equilibrium. Gradual change is necessary and desirable and typically stems from such things as population growth, technological advances, and interaction with other societies that brings new ways of thinking and acting.

However, sudden social change is undesirable because it disrupts this equilibrium. To prevent this from happening, other parts of society must make appropriate adjustments if one part of society sees too sudden a change. |

| Conflict theory | Because the status quo is characterized by inequality and other problems, sudden social change in the form of protest or revolution is both desirable and necessary to reduce or eliminate inequality and to address other social ills. |

| Theoretical Perspective | Major Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Symbolic interactionism | Social organization emerges from shared meanings created and communicated via symbols and interactions.

Social identities are shaped by social processes. Any significant change in the situation, environment, or activity prompts a re-evaluation of the meanings that people entertain. Ideas about the world change as we see how others see them and are affected by ideas others believe. In social reality, the truth of an assertion changes with the times. |

Let’s look at these sociological theories through an example. RACE TALKS: Uniting to Break the Chains of Racism is an organization based in Portland, Oregon. Its organizers envision “a world beyond superficial connections where race, ethnicity, gender, and religion are no longer barriers to connecting with others, but a means to enhance cross-cultural connections through deep and shared experiences” (“Our Story” n.d.).

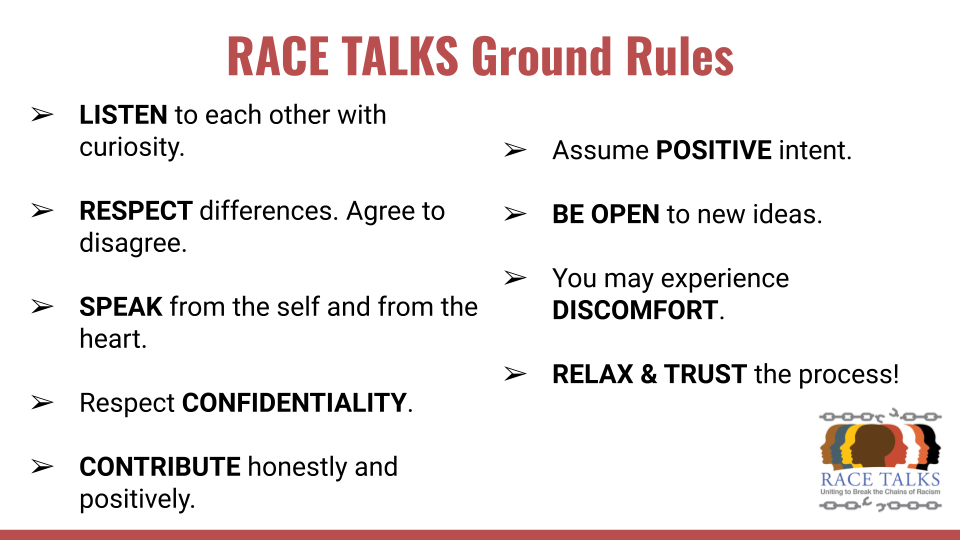

Since 2011, the organization has hosted monthly events at a popular venue, engaging a total of over 30,000 participants. The events begin with providing a platform for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) to present their work or current issues. Then all participants discuss the topics of the evening in facilitated conversations (figure 3.34).

Donna Maxey is the founder of RACE TALKS. She’s a former teacher and activist who was motivated to address social divisions that are due to systemic oppression, inequity, privilege, and violence. She’s a Black woman whose parents fled East Texas in the early 1940s due to the Jim Crow laws—state and local legal codes that enforced racial segregation. Their new state of Oregon, however, escaped Jim Crow laws merely because Oregon was a whites-only state that already had exclusionary laws against Black people (laws not removed from the books until 2002). Oregon remains one of the whitest states in the United States, and as in the rest of the country, organized white supremacist groups are on the rise (Southern Poverty Law Center n.d.).

Take a look at Donna Maxey, founder of Race Talks [Streaming Video] (figure 3.35). There, Donna describes her inspiration and strategy for making social change. As you watch, consider the RACE TALKS project through the lens of both symbolic interactionism and conflict theory. That is, how can you apply social interactionism to explain the role and success of RACE TALKS? How can you explain the changes RACE TALKS aims to make through the lens of conflict theory?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0rZl5wrchMM

Licenses and Attributions for Classical Sociological Perspectives

Open Content, Original

“Classical Sociological Perspectives” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The introductory paragraph is adapted from “1.1 The Sociological Perspective” in Local to Global: The Sociological Journey by Christina Miller-Bellor and Donna Giuliani, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“Structural Functionalism” is adapted from “2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Photo (figure 3.29) added, sections edited, and content expanded.

Figure 3.29. Pilgrim in supplication at the Masjid Al-Haram in Mecca is on Wikipedia and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.

“Conflict Theory” is adapted from “2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Photo (figure 3.30) added, sections edited, and content expanded.

Figure 3.30. Bristol Museum vs. Banksy / Rickshaw on Flickr by JasonBlait is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“Symbolic Interactionism” is adapted from “2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Photo added (figure 3.31) and content expanded for social change context.

Figure 3.31. Standing Up For Ferguson on Flickr by Joe Brusky is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 (left). “Hands up gloves” on Flickr by Justin Norman is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (right).

Figures 3.32 and 3.33 are adapted from the Theory Snapshot table in “Sociological Perspectives on Social Change,” “20.1 Understanding Social Change,” in Sociology by University of Minnesota, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and “1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology,” “Macro and Micro Approaches,” by Jean M. Ramierez; Suzanne Latham; Rudy G. Hernandez; and Alicia E. Juskewycz in Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Content on Symbolic Interactionism replaced.

Figure 3.35. Donna Maxey, founder of Race Talks by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.34. Image of ground rules for the facilitated conversations is found on the RACE TALKS: Uniting to Break the Chains of Racism website and included under fair use.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the observation that society is always in a natural state of equilibrium, defined as a state of equal balance among opposing forces.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

the set of people who share similar social circumstances based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

the labeling or spoiling of an identity, which leads to ostracism, marginalization, discrimination, and abuse.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.