3.3 The Study of Social Location

The story of Colombia’s class inequality and how it influences conflict is one that plays out all over the world. Class inequalities played a major role in the conflict there, and they still exist today. Social class is one of the main characteristics that sociologists pay attention to when they examine humans’ place in the social world.

Another way to explain our place in the social world is with the term, social location: the social position an individual holds within their society based upon their social characteristics. Other than social class, these characteristics include race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, ability, immigration, language, employment, and other characteristics that society deems important.

Sociologists work to understand these kinds of interactions and patterns related to inequality and how they affect life experiences. This section will look deeper into a few ideas that frame their study of social location: levels of analysis, the social construction of identity, and the consequences of social locations.

Levels of Analysis

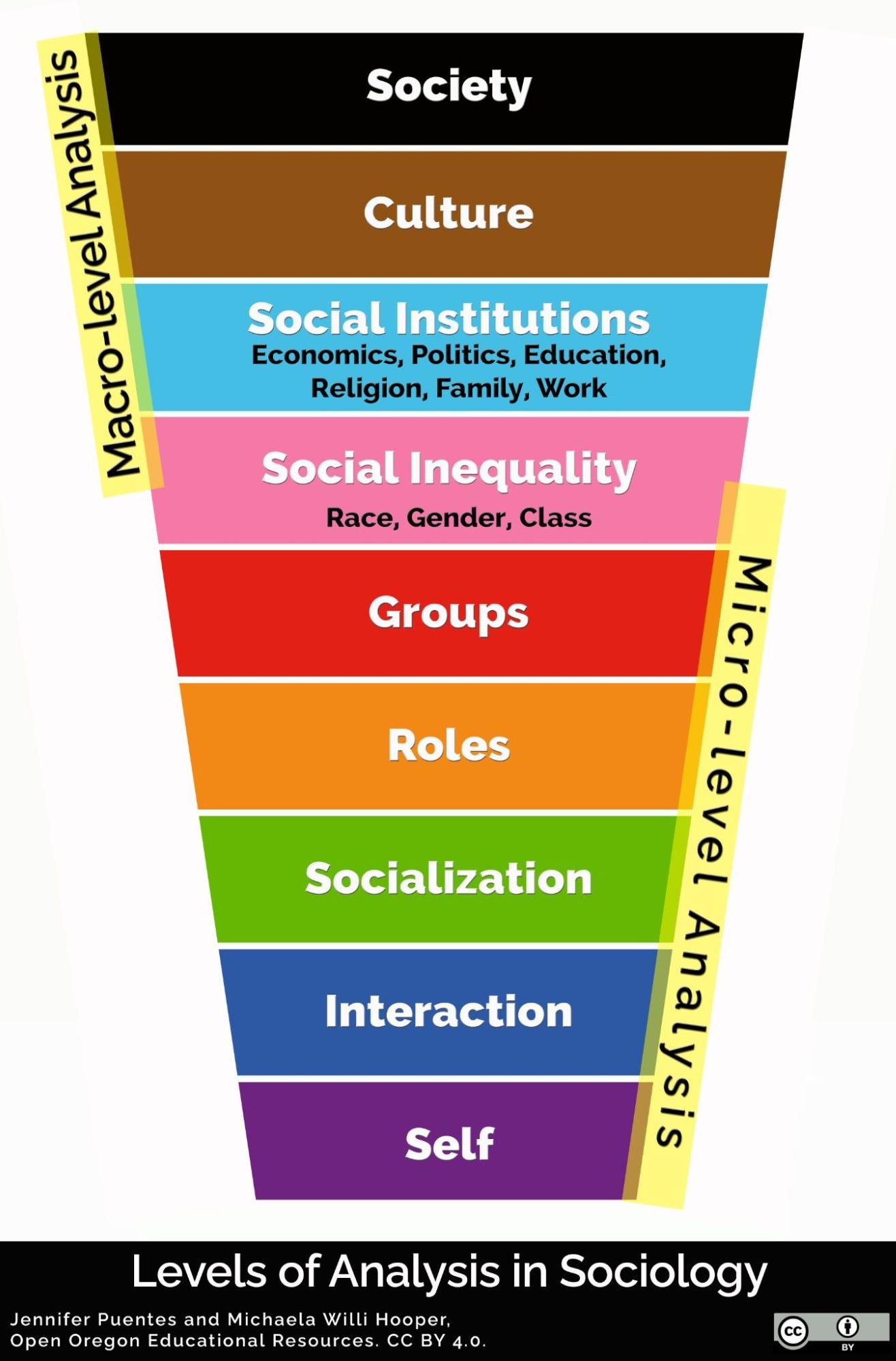

Sociologists study at multiple levels of society—that is, they focus on various sizes or scales of the population or social phenomenon. Generally, they examine the effects of our social locations, as well as all other inquiries about society with either a macro or a micro lens. This is also referred to as microsociology and macrosociology (figure 3.5).

Micro-level analysis examines how individuals respond to society around them and the interaction of small groups. According to sociologist Randall Collins, the micro level involves analyzing “what people do, say, and think in the actual flow of momentary experience” (Collins 1981:984).

Microsociology focuses on socialization, the lifelong process of learning what is expected behavior in society. Through social interaction, socialization teaches customs and norms, the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies. It also focuses on roles, or our positions in society that contain socially defined expectations based on our place in society. The micro level allows us to examine how and why individuals interact and how they interpret the meanings of their interactions. Examining society at the micro level, we know that through our interactions with others, society shapes our attitudes and behavior. We still have freedom, but that freedom is limited by society’s expectations.

When sociologists use a macro-level analysis, they focus on the big picture. They study large-scale social structures. The aspects of society that exist over extended periods, such as changes in economies, changes in populations, and the longer course of human societies (Collins 1981). Studying at the macro level often includes looking at trends among and between societies, institutions, and systems. Research could focus on culture shared by larger groups or how one institution impacts another.

Often macro and micro sociologists look at the same phenomena, and they both examine how inequality exists, but in different ways. Microsociology examines how inequality lives within closer interactions, while macrosociology examines inequality at the level of institutions, culture, and among whole societies. Both types of approaches give us a valuable understanding, but together they offer an even richer understanding.

The Social Construction of Identity

The basis for social locations is the social construction of our identities. In Chapter 2, we introduced the social construction of reality. It explains that as a society, we decide the meaning and value of behaviors, ideas, or objects. This process is ongoing and happens through our everyday social interactions.

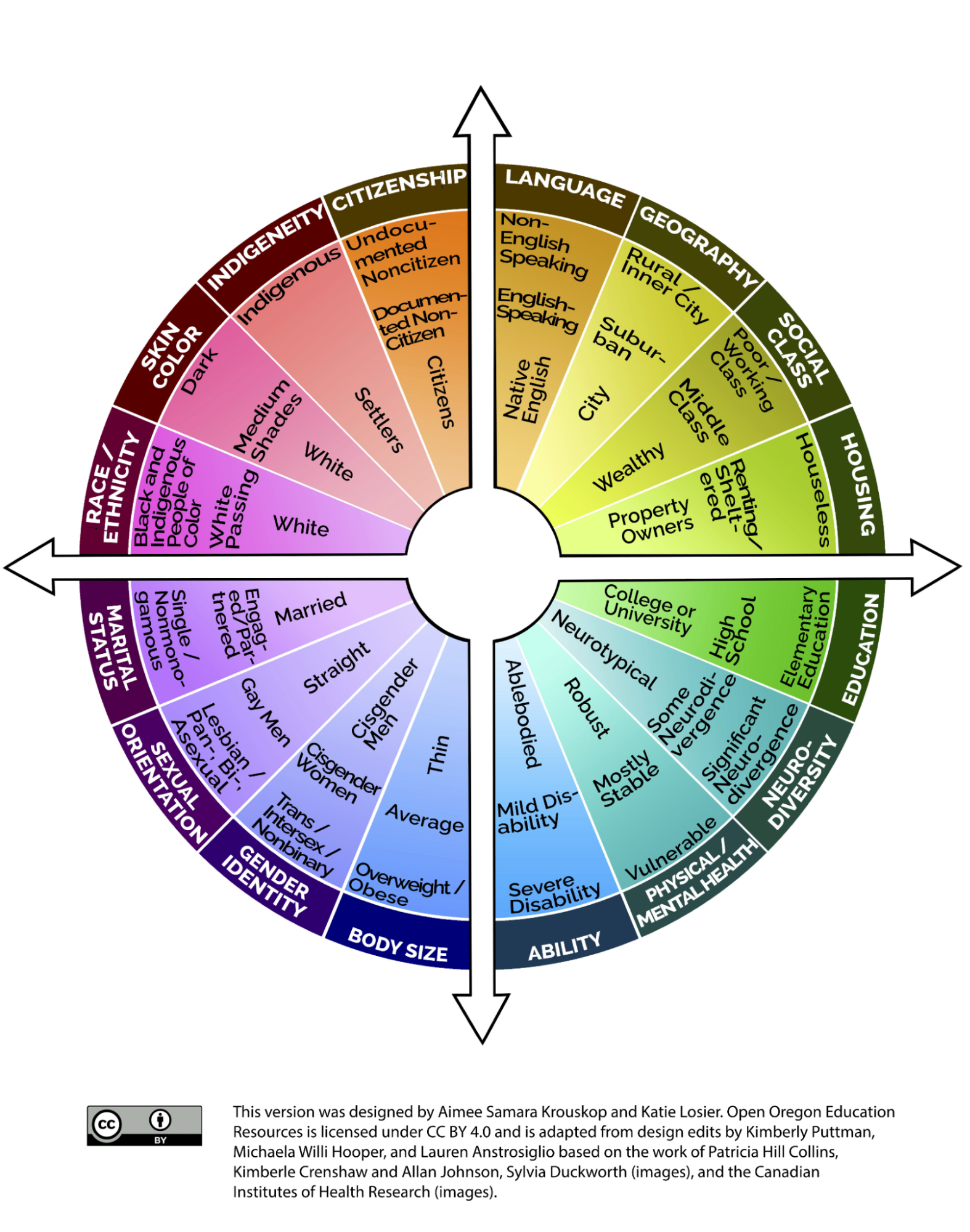

Through this same process, we are all assigned to multiple social categories. Sociologists call these categories social identities, the set of characteristics by which a person is recognizable or known by the society in which they live. Society shapes both the categories through the process of social construction, as well as how individuals are assigned to those groups. We define ourselves, and others define us in terms and categories that we share with other people. Take a look at figure 3.6, which shows some (not all) of the many components that may make up an individual’s or group’s social identity. How many can you identify for yourself?

Our identities are always in flux. That is because the way we think of ourselves and present ourselves to others is created and constantly changes based on our interactions with others. Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley believed our sense of self is based on this idea: we imagine how we look to others, interpret their reactions, and then develop our personal sense of self (Cooley 1902). In other words, people’s reactions to us are like a mirror that reflects who we are.

(Optional: Watch Jason Silva’s passionate discussion about the social construction of our identities in the 2-minute video, “Are We Who We Think We Are?” [Streaming Video] (figure 3.7). In what ways are you constructing your identity based on what you think others think of you?)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7g3IdyOjMU

We build our social identities through a fluid, constantly changing internal process that is influenced by others. Our social identities are also built externally, as society is constantly creating categories and assigning membership to those categories. The degree to which society ascribes our identities to us versus how much we have self-claimed our identities can depend on how aware we are of social expectations. Let’s look at a few categories of identity that hold particular importance in the United States today.

Gender and Sexual Orientation

Many sociologists view gender and sexual orientation identity from a constructionist approach. Through the constructionist lens, we shape our gender and gender expressions socially. Gender identity is a person’s deeply held internal perception of their gender. This includes the roles and behaviors of girls, women, boys, men, and gender-diverse people. Gender expressions are the behaviors, mannerisms, interests, and appearance associated with gender identities. Neither gender identities nor expressions are confined to a gender binary, the notion that someone is either male or female. Gender identity and expressions exist along continuums.

There is considerable diversity in how individuals and groups understand, experience, and express gender and sexual orientation. This is based on the roles they take on, the expectations placed on them, relations with others, and the complex ways that gender is institutionalized in society.

The abbreviation LGBTQIA+ currently represents lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (and questioning), intersex, asexual, and other identities. However, the language and symbolism of gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation are continually changing. They adapt to meet the needs of the members they represent. For example, for Owen Keehnen, co-founder of the advocacy initiative Legacy Project, the grouping together of “LGBTQIA+” serves to create solidarity and political power, as illustrated in figure 3.8.

If I consider myself part of the gay community I look at my core group one way…but if I consider myself part of the LGBTQ community, my group is suddenly much larger, much stronger.…Presenting a unified front adds protection, power and, at the same time, an expanded view of what it means to be a part of this movement (Daley 2017).

Abbreviations and other symbols change in order for the identities of members of LGBTQIA+ communities to be made more visible. They also change as communities work out ways of being inclusive, and so they serve as better tools for making political change (figure 3.9). See the Going Deeper section for a resource list of some of the most commonly used terms in these communities.

The binary view of gender is specific to certain cultures and is not universal. In some cultures, gender is viewed as fluid. For example, Samoan culture accepts what Samoans refer to as a “third gender.” Fa’afafine, which translates as “the way of the woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but embody both masculine and feminine traits (Poasa 1992).

Those who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth are often referred to as “cisgender,” utilizing the Latin prefix cis, which means “on the same side.” For example, a child is assigned female at birth and later self-identifies as a woman.

“Transgender” refers to a person whose sex assigned at birth and gender identity are not necessarily the same. A transgender woman is a person who was assigned male at birth but who identifies and/or lives as a woman; a transgender man was assigned female at birth but identifies and/or lives as a man. While determining the size of the transgender population is difficult, it is estimated that 1.4 million adults (Flores 2016) and 2 percent of high school students in the United States identify as transgender (Johns 2019).

In much the same way that sociologists study gender, they study sexual orientation—the enduring patterns of romantic or sexual attraction (or combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. They study sexual orientation as a social construct and identify that the categories of our sexual orientations also live outside of the binary (the notion that someone is either attracted to men or women).

“Queer” is a term used to describe gender and sexual identities other than cisgender and heterosexual. The term queer has been used in different ways and has many different meanings. Originally, in the 19th century, the term came to be used in a derogatory way toward those with same-sex desires or relations. Starting in the late 1980s, queer activists began to reclaim the word and embraced it as a politically radical alternative to other LGBTQIA+ identity terms (Sycamore 2008).

The social construction of gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation can change over time. For example, behaviors that are associated with femininity and masculinity reflect culture and patterns of interaction that are considered acceptable during certain historical time periods. Characteristics of gender may also vary greatly between different societies. For example, in U.S. culture, it is considered feminine (or a trait of the female gender) to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, sarongs, robes, or gowns are considered masculine.

Ethnic and Racial Identity

Often, the terms race and ethnicity are used interchangeably, but there are differences between them. Ethnicity refers to categories of social difference organized around shared cultural factors such as nationality, language, history, faith, or tradition. Race is a socially defined classification based on perceived biological differences between various people and groups. Race assigns social, cultural, and political meaning and consequences to physical characteristics.

Race is a social construction created to classify people on the arbitrary basis of skin color and other physical features. On a biological level, there is no real concept of race. The Human Genome Project was an international research project completed between 1990 and 2003 that determined all human beings, despite perceived racial group categories, are 99.9 percent genetically identical (Collins et al. 2003). This is consistent with the sociological argument of race being a social construct (figure 3.10).

Sociologists examine the social, economic, and political forces that result in ethnic and racial identities. Every culture places a different importance on specific physical characteristics. For example, in the United States, race is identified by broad categories of skin color, but hair color is considered unimportant. In South America, there are more specific categories of skin color. (Optional: Watch this 3-minute VOX video, “The Myth of Race, Debunked in 3 Minutes” [Streaming Video], to hear more about race as a social construct. Does anything surprise you?)

Understanding the social construction of identity and levels of analysis can help us understand the consequences of the categories society creates. First, each component of our identity carries power, benefits, or disadvantages. In other words, each category is associated with a hierarchy of dominant and non-dominant groups. Dominant members, because they hold more power, can limit opportunities to members that fall into “other” categories. Or they can bestow benefits to members they deem “normal” or who follow their standards of acceptable behavior and presentation. This is one way that social location is assigned. Second, we can observe and study the consequences of our social locations at any level of analysis to gather a whole picture of our interactions.

The Consequence of Social Location

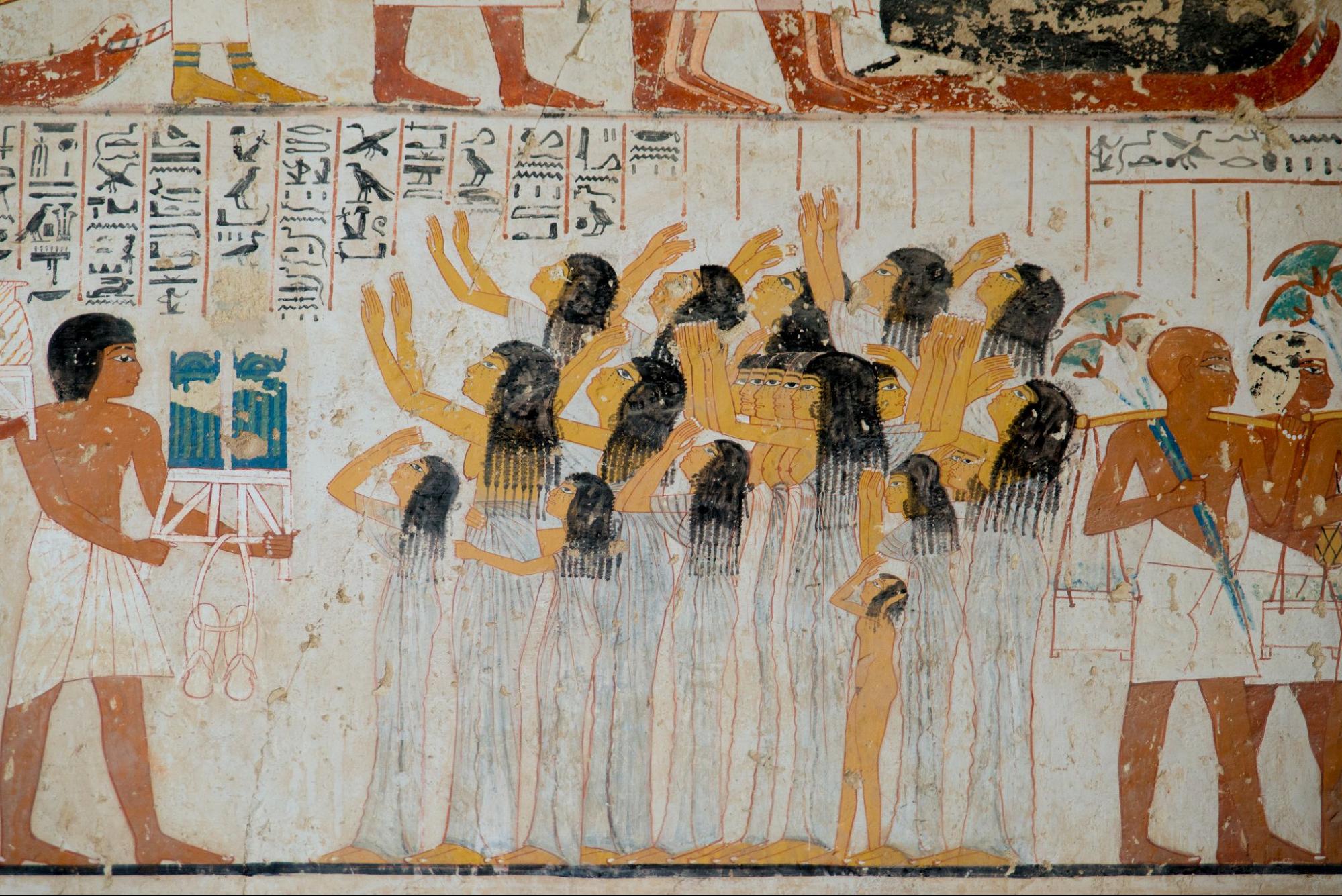

Another way of seeing social location is through the layers of society. Sociologists identify nearly every society as having some form of social stratification, or categorization of its people into rankings based on factors of power, access and resources, (such as wealth, income, education, or occupation) as well as social identities (like, race, ethnicity, or gender) (figure 3.11). Typically, society’s layers, made of people, represent the uneven distribution of society’s benefits. The people with more power, resources, and access sit at the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with fewer power, resources, and access, represent the lower layers.

The macro lens allows us to see societies as a whole as stratified. A micro lens allows us to see individuals’ place within this stratification. This place is called social status—the rank, honor, or prestige attached to one’s position in society or a group. Your social location influences your status in society.

Sociologists look to see if individuals with similar backgrounds, group memberships, identities, and location share the same place in the social stratification system. One common way to evaluate social standing is with socioeconomic status, a combination of a person’s or family’s economic and social position in comparison to others, based on income, education, and occupation.

No individual, rich or poor, can be blamed for social inequalities. Instead, everyone participates in a system where some rise and others fall. Many people in the United States believe this rising and falling is based on individual choices. But sociologists see how the structure of society affects a person’s social standing and, therefore, is created and supported by society.

Social location affects how others perceive and treat us, how we perceive and act in the world, and how we build relationships. For example, core to the study of social location in the United States is understanding normalization. Introduced by sociologist Michel Foucault, normalization in this sense is a process that constructs specific ideas and behaviors as the idealized norms. These idealized norms are created through sanctions or corrections. Some identities are more highly valued, or more normalized, than others—typically because they are contrasted to identities thought to be less valuable or less “normal.” Thus, identities are not only descriptors of individuals but also grant a certain amount of collective access to the institutions of social life.

For example, among many people in the United States, wealth is associated with an idealized norm—that is, the behaviors and ideas of those with more income or wealth are considered more valuable. This contributes to classism, a prejudice or discrimination on the basis of social class. However, that normalization may be changing. The Pew Research Center found in 2020 that more U.S. residents believe that having personal fortunes of a billion dollars or more is a bad thing for the country (Daniller 2021).

With microsociology, sociologists can study the consequences of social location at the “self” level of analysis (figure 3.5) by asking specific questions about how individuals in specific groups experience society. Or, with macrosociology, they can study experiences at the “institutions” level (figure 3.5) by asking how our larger social systems serve people in different groups. We’ll introduce more of these ideas in the context of white identity in the next section, White Culture and Institutional Racism.

Going Deeper

To better understand connections between microsociology, macrosociology, and the classical perspectives, watch this 3:37-minute video, “Microsociology vs. Macrosociology” [Streaming Video] by Khan Academy.

For a good glossary of words related to identity of all sorts, see the Race Equity Tools Glossary [Website].

For an overview of some of the most commonly used terms of the LGBTQIA+ communities, explore the Trans Student Educational Resources Online Glossary [Website].

For more information on advocacy for transgender and gender-nonconforming students (and others), see the graphics page of the Trans Student Educational Resources website.

To understand more about race as a social construct in the United States, read the AAPA statement on race and racism [Website].

Learn more about race as it relates to human genetics in the Teaching Tolerance report “Race Does Not Equal DNA” [Website].

For insights on how we develop our racial identities, see this Racial Identity Development page [PDF].

Licenses and Attributions for The Study of Social Location

Open Content, Original

“The Study of Social Location” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Levels of Analysis” is a remix of “Levels of Analysis: Macro Level and Micro Level” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0 with minimal content from “1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Content added on socialization and inequality.

Figure 3.5. “Levels of Analysis” is found in “Levels of Analysis: Macro Level and Micro Level” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.6. Social identity wheel is designed by Aimee Samara Krouskop and Katie Losier and licensed under CC BY 4.0. It is adapted from design edits by Kimberly Puttman, Michaela Willi Hooper, and Lauren Anstrosiglio based on the work of Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberle Crenshaw and Allan Jonhson, with Syvia Duckworth (images) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (images).

“Gender and Sexual Orientation” is adapted from “9.2 Sex, Gender, and Identity” by Jennifer Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Abridgement and summaries created from content. Pride celebration mural added (figure 3.8). Content added: on changing abbreviations and symbols for LGBTQIA+ including Figure 3.9, and logo of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF).

“The Consequence of Social Location” includes limited content from “Conceptualizing Structures of Power” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.8. Pride celebration mural by Sam Kirk on Flickr by Terence Faircloth is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 3.9. Logo of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) on Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

Figure 3.11. Ramose Theban Tomb TT55 on Flickr by kairoinfo4u is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.7. “Are We Who We Think We Are?” by Jason Silva: Shots of Awe is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.10. Screenshot from video, “The Myth of Race, Debunked in 3 Minutes” is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the set of people who share similar social circumstances based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

the lifelong process of an individual or group learning the expected norms and customs of a group or society through social interaction.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the set of characteristics by which a person is recognizable or known by the society in which they live.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the categorization of its people into rankings based on factors of power, access and resources, (such as wealth, income, education, or occupation) as well as social identities (like, race, ethnicity, or gender).

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

the rank, honor, or prestige attached to one’s position in society or a group.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a combination of a person's or family's economic and social position in comparison to others.

a process that constructs specific behaviors, presentations, and ideas as the idealized norm through correction.