1.4 Social Problems and Social Justice

Kimberly Puttman

As we conclude this chapter, you may be feeling curious and excited to know more. You may be feeling depressed, angry, or despairing because the weight of even the few social problems we have begun to explore is enormous. We’ve explored the differences in hunger worldwide. We’ve examined how our understanding of sexual assault is socially constructed. We’ve analyzed a model in order to understand how social problems work. And we’re only on Chapter 1.

Social problems sociologists don’t stop with the problem, though. They do their research to discover solutions and use them in the world. They are committed to addressing the suffering of people who experience these problems. They look for solutions at all levels using both individual agency and collective action. You may be wondering which approach is more effective.

To confront the social problems of our world, we need a both/and approach to their resolution. We act with individual agency to create a life that is healthy and nurturing, and we act collectively to address complex issues. Among many scholar/activists, two women embody the power of this approach.

The following biographies introduce two researcher/activists embodying study and action. With scholar-activists leading the way, we will explore the causes and consequences of social problems locally, nationally, and internationally. Each chapter in this book will explore reasons for hope—those leaders, ordinary people, and community groups actively engaged in creating a more just, equitable, and resilient world.

Activist Scholars: Jane Addams and Angela Davis

The good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain… until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life.

-Jane Addams, community activist, scholar, and Nobel Prize winner

Jane Addams (Figure 1.16) was a wealthy White woman who combined community building, research, and activism. During her lifetime, the US was grappling with industrialization, urbanization, immigration, World War I, and the Great Depression. Addams responded to these challenges with action.

Addams created and lived at Hull House, a Chicago community center for immigrants in the late 1800s. Hull House was a center for kindergarten and daycare for children, where teachers taught adults and children to read and speak English. Community members could get help in finding jobs and learning about union activities. In creating Hull House, Jane Addams used both individual agency and collective action.

In addition to being a community activist, Addams was a scholar and a researcher. She studied the causes of the social problems she saw. Even though she was not allowed to attend a regular university because she was a woman, she worked with the male sociologists at the University of Chicago School of Sociology to understand the deep roots of poverty, hunger, and violence in her Chicago neighborhood.

She was also a thought leader in identifying the causes and consequences of poverty and oppression. In addition, she created a network of peace activists and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 for her efforts in promoting international peace (Michals 2017). Her work for social justice included both community action and scholarly reflection. If you’d like to learn more about Jane Addams and her work at Hull House, watch this video documentary about Jane Addams [YouTube], or read this biographical statement for the Hull House Museum.

You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.

-Angela Davis

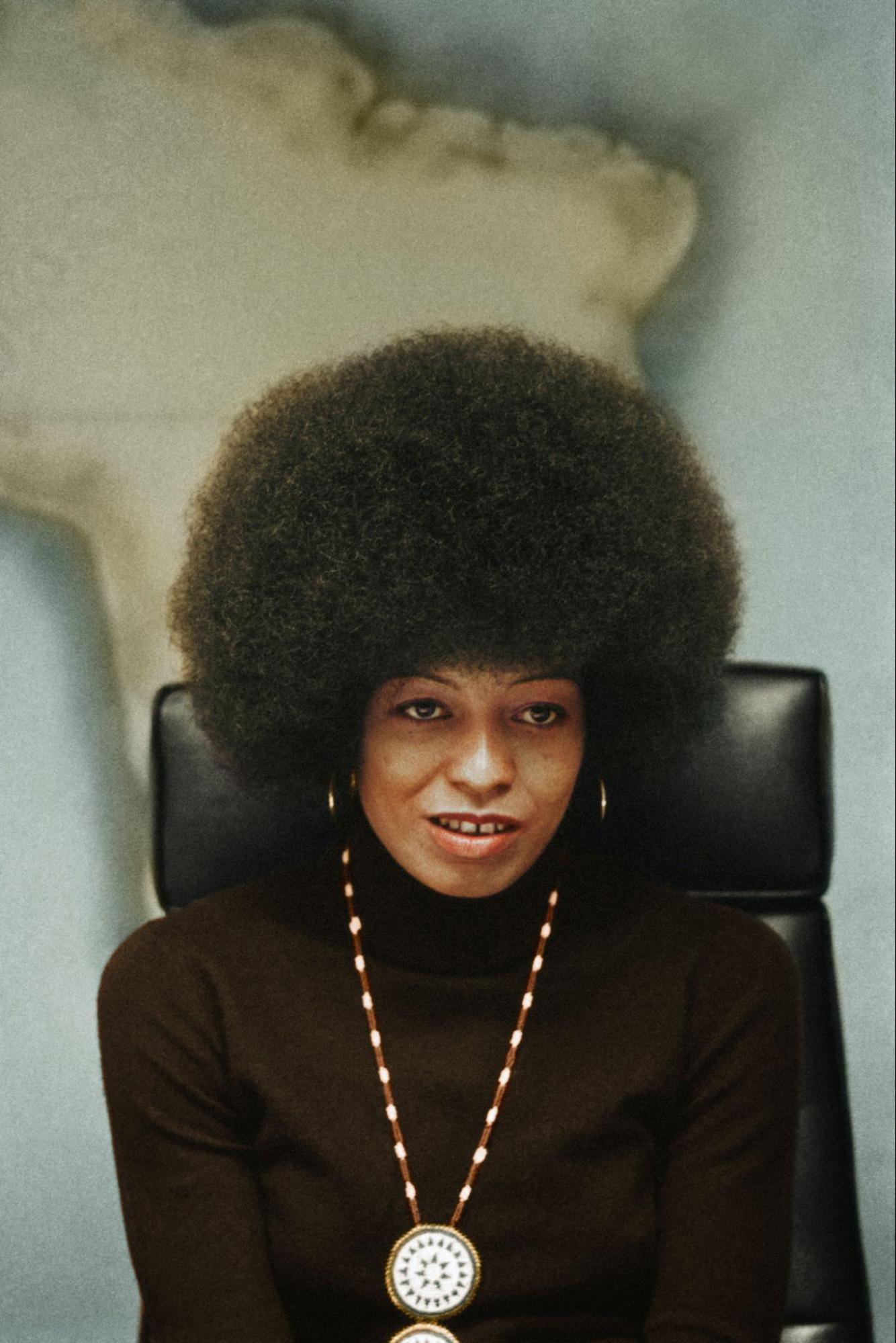

Black activist and scholar Angela Davis (Figure 1.17) is another woman who embodies the power of both/and thinking when combining individual agency and collective action.

The challenges of her time included the Vietnam War. The sociologist C. Wright Mills developed the idea of the military-industrial complex—that military spending related to war led to profits for wealthy businessmen (Rosen 1973). Also, some women agitated for equality in work and home as the second wave of feminist activism was building. As we’ve discussed earlier in this chapter, protesters in the civil rights movement were fighting to end segregation and win equality in voting, housing, education, and other social spheres.

In this tumultuous time of social change, Davis started her career as a scholar but soon became an activist protesting the unjust treatment of three Black prisoners in 1970. The combination of scholarship and activism led her to study the deeper causes of the expansion of the prison system. She coined the term prison-industrial complex, the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment to solve economic, social, and political problems (Tufts University Prison Divestment 2023). She saw that Black and Brown men were disproportionately imprisoned and that wealthy corporations and governments benefited from it. Her passionate commitment to radical social change, supported by careful critical analysis, continues today. She says, “The real criminals in this society are not all of the people who populate the prisons across the state, but those who have stolen the wealth of the world from the people.” (Davis quoted by George 2020).

With others, she founded Critical Resistance in 1997, an organization to abolish the prison industrial complex. She sees this as part of a bigger goal of liberation for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, and for the liberation of women, queer, and transgender people. In one New York Times article, the author writes, “Before the world knew what intersectionality was, the scholar, writer, and activist was living it, arguing not just for Black liberation, but for the rights of women and queer and transgender people as well” (George 2020). She co-wrote a book called Abolition. Feminism. Now. in which Davis and her co-authors connect racist policing and gender violence. In an interview related to the book, Davis says,

The feminist mention of abolition is not simply that we want to attend to women and nonbinary people who are survivors of state violence and intimate violence, but that we want to understand the connections between violence that is perpetrated by the police and violence as perpetrated by someone with whom the survivor imagined themselves in love. That is the essence of the feminist dimension of abolition, that it not simply focuses on discrete projects of getting rid of the police or getting rid of the prison, but that we understand the economic connections, the relationship to global capitalism and struggles in other parts of the world. ( Davis in Meiners et al 2022)

This is a complicated quote, but for now, it is useful to recognize that Davis and her co-authors are seeing interconnected social problems and interdependent solutions in their fight for social justice.

Davis embodies both/and approaches to addressing social problems, taking individual action to care for herself and others, and connecting activists in social activism. She advocates for social justice and liberation. If you would like to learn more, consider exploring Angela Davis’s early activism [YouTube], read her work on the prison industrial complex in Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex [Website], or listen to this speech: Angela Davis talks at Southern Illinois University Carbondale [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for Social Problems and Social Justice

Open Content, Original

“Social Problems and Social Justice” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.16. “Jane Addams” by Gerhard Sisters is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.17. “Angela Davis” by Bernard Gotfryd has no known copyright restrictions. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change, free will, or self-determination.

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.

full and equal participation of of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs

the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.

a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms

the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.

a person who does not conform to norms about sexuality and gender (particularly the ones that say that being straight is the human default and that gender and sexuality are hardwired, binary, and fixed rather than socially constructed, infinite, and fluid).

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.