3.2 How Do You Know?: Social Theory

Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman

When you consider what you wear today, you may look into your closet or the clean clothes on your floor and make some choices. Perhaps the red dress suits your mood or the green gardening clogs help you get your work done for the day. These personal choices are yours to make. At the same time, what you choose to wear is also influenced by your gender identity, social class, race or ethnicity, or even whether or not you use a wheelchair.

As scientists, sociologists want to understand the causes of the social forces that influence what you wear, for example. They want to see why you have jeans made in Vietnam as one of your choices (Figure 3.2). They consider why some women wear hijabs (Figure 3.3), and some men wear turbans (Figure 3.4). They might look at how clothing helps distinguish a particular culture or ethnic group (Figure 3.5). Sociologists of gender might examine who wears makeup and who doesn’t (Figure 3.6).

Sociologists observe and measure social behavior to explain or predict the actions of people or groups, one of the ways to do science. For example, when sociologists examine what kind of clothing people wear, they might use the concept of cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation is the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture (O’Keefe 2020). In the student-created image in Figure 3.7, the student was comparing fashion between Mexican American and White women. She noted that when Mexican American women wear braids and outline their lips in brown, they are called trashy. When White women do a similar thing, they are called pretty or cute. Sociologists explain these differences using theories of race and gender.

However, science isn’t the only way to understand the world. You may experience many more ways of knowing. When you consider why you know something, this knowledge may be based on different sources or experiences.

You may know when the movie starts because a friend told you or because you looked it up on Google. You may know that rain is currently falling because you feel it on your head. You may know it is wrong to kill another person because it is a belief in your religious tradition or part of your ethical understanding. You may know because you have a gut feeling that a situation is dangerous or a choice is the right one. You may know that your friend will be late to class because past experience predicts it.

Or, instead of the past, you can imagine the future, knowing that eating a hamburger will satisfy your hunger just by seeing the picture on the menu. Finally, you may know something because the language you use supports you in noticing particular details. For example, how many ways can you describe the water that falls from the sky? People who live in Oregon use several distinct words for rainy weather like drizzle, downpour, and showers. Partly cloudy doesn’t change their plans, but they may throw a jacket in the car. In other regions, it may be more useful to describe snow or heat in greater detail. The formation of language itself structures how you know something. The table in Figure 3.8 organizes these ways of knowing.

| Way of Knowing | Example |

|---|---|

| Emotion | Psychologists define common human emotions as happiness, sadness, disgust, fear, surprise, and anger. Knowing that your child is sad may help you to parent better. |

| Faith | Commonly, faith is defined as a belief in God. However, you can also have faith that humans are generally good, or that things will work out OK in the end. |

| Imagination | A social activist proposes a different vision of how people use fossil fuels to power cars. |

| Intuition | Einstein had a flash of insight about how light travels. |

| Language | “They” as a singular pronoun supports the idea that gender can be nonbinary. |

| Memory | By remembering how you studied effectively for the last test, you know how to study for the next test. |

| Reason | You measure the amount of time that students talk in a classroom, and who the teacher calls on to learn about gender bias in the classroom. Reason depends on gathering facts. |

| Sense Perception | When you touch a hot stove, your sense of touch registers HOT! |

Each of these ways of knowing is useful, depending on the circumstances. For example, when my wife and I bought our house, we did research on home prices, home loans, and market value—reason. We talked about what home felt like to us—emotion. We walked through houses and pictured what life would look like in a particular house—imagination. Ultimately, when we drove down the cedar and fir-lined driveway, welcomed by the warm light through the window—sense perception—we turned to each other and said, “I hope this house is still for sale,” because we both knew we had found our home—intuition.

Of all of these ways of knowing, though, reason allows us to use logic and evidence to draw conclusions about what is true. Reason, as used in science, is unique among all the ways of knowing because it allows us to propose an idea about how a social situation might work, observe the situation, and determine whether our idea is correct. Sociology is a unique scientific approach to understanding people. Let’s explore this more deeply.

As a reminder, sociology is the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand our social world. Although sages, leaders, philosophers, and other wisdom holders have asked what makes a good life throughout human history, sociology applies scientific principles to understanding human behavior. The first question they often ask is, “Why does the social world work the way it does?”

They answer that question by proposing and testing theories. Scientists pose theories to explain how and why society works the way it does. More specifically, a theory is a statement that describes and explains why social phenomena are related to each other. Theories help us to understand patterns in social behavior.

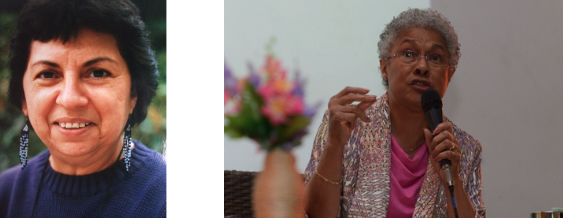

For example, Gloria Anzaldúa and Patricia Hill Collins are well-known sociologists who created theories that explain racial, ethnic, and gender oppression (Figure 3.9).

In this section, we discuss historical and contemporary theories and theorists that assist us in thinking deeply about the causes and consequences of social problems, such as racism, poverty, and discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Using social theory helps us to understand why social problems exist. This understanding, in turn, can help us better address or prevent them.

Social theory helps us put into words the underlying mechanisms that guide society and our social interactions (Lemert 1999). By analyzing society in this way we can better understand the causes and consequences of social problems.

For example, German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engles tried to understand why workers were protesting against factory owners. You have the option of learning more about Marx and Engles if you wish. Their theory of capitalism helps us understand poverty by outlining the ways profit is generated through worker exploitation. They proposed that revolution was an inevitable outcome of the unequal distribution of wealth between the rich, who owned land and factories, and the poor, who didn’t. According to Marx ([1867] 2012), the worker is not paid the full value of their labor. The business owners, or bourgeoisie, takes a percentage of the value created by the worker and keeps it as profit. The bourgeoisie are always looking for ways to decrease worker wages and increase profit, which results in low-wage work and working poverty. Marx and Engels were revolutionary thinkers because they followed the money—who had it and who didn’t—to explain conflict in society. Marx himself was poor, unlike many sociologists of the time. By analyzing and critiquing capitalism, Marx explained a hidden part of everyday experience. In this way, theory can be liberating because it allows us to better understand the workings of the social world in which we live.

Licenses and Attributions for How Do You Know? Social Theory

Open Content, Original

“How Do You Know? Social Theory” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.8. “Ways of Knowing Table” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Theory” definition is adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 3.2. “Rancher and Wranglers” by Pamela Steege is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 3.3. “Image” by Haifeez is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.4. “Day Trip” by Nayanika Mukherjee is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.5. “Mexican Folk Dancer” by Brendan Lally is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.6. “Applying Lip Gloss” by Chona Kasinger, Disabled and Here is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.9 “Gloria Anzaldúa” by K. Kendall is licensed under CC BY 2.0. “Patricia Hill Collins” by Valter Campanato/Agência Brasil is licensed under CC BY 3.0 BR.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.7. “Cultural Appropriation” © Marisol is all rights reserved and included with permission.

one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither – how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One's gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth.

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion.

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.

the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand individuals, groups, and institutions through data collection and analysis.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.

the unequal treatment of an individual or group based on their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex)

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attractions toward another person

an economic system based on private ownership and the production of profit.

the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns