3.5 Modern and Emerging Sociological Theories

Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman

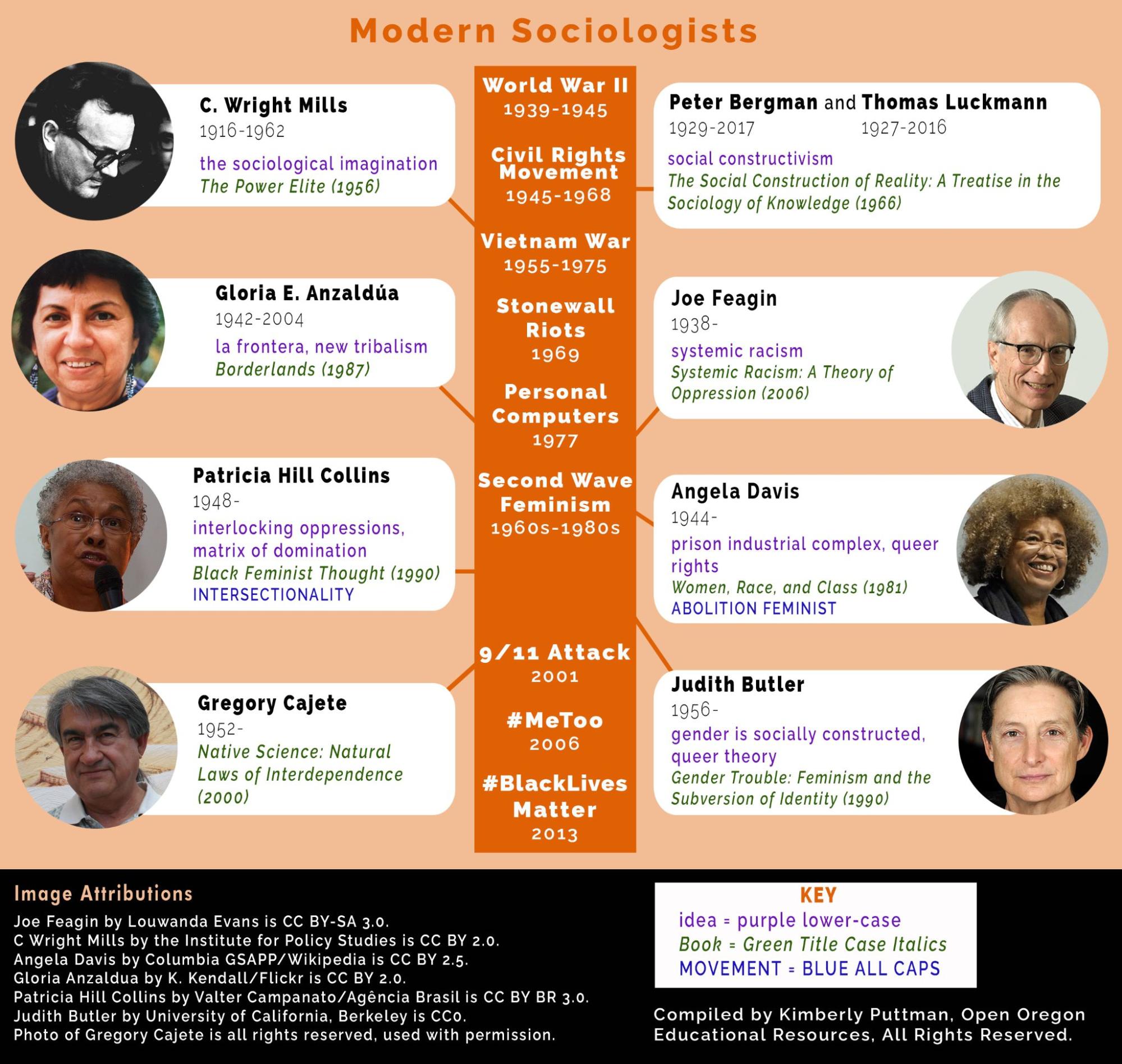

After the Second World War, sociologists expanded on previous sociological thought. They developed a variety of theoretical frameworks that explore race, class, and gender. They explored the intersections between these classifications of power and oppression. While the classical theories remain useful, the new set of theories digs deeper into why structures and practices of inequality persist. They also leverage new understandings of systems thinking and global interdependence. You will meet many of these sociologists in this section.

Feminism and Intersectionality

In early sociology, sociologists often studied the experiences of White wealthy men and generalized what they discovered to “all people.” Du Bois made it clear that race matters. Similarly, early female sociologists asserted that gender matters. Sociologists like Martineau, Wells, and Cooper examined women’s lives to see how they were different from men’s lives. They also looked at how race mattered specifically to women. Although we know today that binary structures of gender do not fully capture the human experience, the sociologists at that time were revolutionary in differentiating women’s and men’s experiences.

In the 1970s, as women began to enter college in greater numbers and more researchers were female, they created a new theoretical approach in sociology. Feminist theory is a theoretical perspective stating women are uniquely and systematically oppressed and that challenges ideas of gender and sex roles. Despite the variations between different types of feminist approaches, four characteristics are common to the feminist theory:

- Gender is a central focus or subject matter of the perspective.

- Gender relations are viewed as a problem: the site of social inequities, strains, and contradictions.

- Gender relations are sociological and historical in nature and subject to change and progress.

- Feminism is about an emancipatory commitment to change: the conditions of life that are oppressive for women need to be transformed (Little 2014).

One of the sociological insights that emerged with the feminist perspective in sociology is that “the personal is political” (Hanisch 1969). In other words, how women live their lives from washing dishes, to caring for children, to deciding not to have children, to the experience of sexual violence give them a unique political perspective. Until female sociologists looked at women’s lives, their experiences were invisible or unimportant. You are welcome to read more about the Personal Is Political.

White British-born Canadian sociologist Dorothy Smith’s development of standpoint theory was a key innovation in sociology that enabled women’s experiences and issues to be seen and addressed in a systematic way (Smith 1977). Scientists of the time argued that science was logical and objective. In standpoint theory, Smith argued that where you stand, or your point of view, influences what you notice (Smith 1977). Women and other marginalized people see systems of oppression more clearly because they experience them. Smith recognized from the consciousness-raising groups initiated by feminists in the 1960s and 1970s that academics, politicians, and lawyers ignored many of the immediate concerns expressed by women about their personal lives. You have the option to learn more about Dorothy Smith and consciousness-raising if you’d like.

Part of this blindness was caused by the way sociology was traditionally done by men. Smith argued that instead of beginning sociological analysis from the abstract point of view of institutions or systems, women’s lives could be more effectively examined if one began from the “actualities” of their lived experience in the immediate local settings of “everyday/everynight” life. She asked, “What are the common features of women’s everyday lives?”

From this standpoint, Smith observed that women’s position in modern society is acutely divided by the experience of dual consciousness. One consciousness was centered in family. Then they had to cross a dividing line as they went out in the world, dealing with work or the institutions of schools, hospitals, and governments. Women had to use a second consciousness to navigate this. These institutions didn’t see women’s real and personal understandings of the world (Smith 1977).

The standpoint of women is grounded in relationships between people because they have to care for families. Society however, is organized through “relations of ruling,” which translate the substance of actual lived experiences into rules and laws. Power and rule in society, especially the power and rule that limit and shape the lives of women, operate as if there is one objective reality, rather than differences in people’s lived experiences. Smith argued that the abstract concepts of sociology, at least in the way that it was taught at the time, only contributed to the problem. This theory, while it seems obvious now, was revolutionary at the time. And, though groundbreaking, it had its limits.

The feminist perspective within social theory has changed throughout the years. From the 1800s until the mid-twentieth century, the central focus or subject matter was differences between women and men. Race and class were generally ignored. Black feminists pointed out that previous forms of feminist theory were mostly concerned with the issues of White middle-class and wealthy women. This was a critical intervention into the perspective of feminist theory.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TFy4zRsItY

Early Black feminist theorists built the foundation for the study of feminist intersectionality. Intersectionality, as you read in Chapter 2, is a perspective and a theory that analyzes and interrogates the ways race, class, gender, sexuality, and other social structures of privilege and oppression overlap and work together.

The concept of intersectionality emerged from a critique of White feminist theory and activism that ignored the experiences of Black and Indigenous women of color. The 4.05 minute video What is Intersectional Feminism? [Streaming Video] (Figure 3.17) describes this approach.

The roots of intersectional feminism can be found in the work of Anna Julia Cooper (1858–1964) and Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931). In their own ways, Cooper and Wells-Barnett brought a sociological consciousness to their response to the Black experience and focused on the toxic interaction between difference and power in US society (Madoo and Niebrugge 1998).

Cooper and Wells-Barnett looked at society through the lenses of race, gender, and class. Although they worked separately, they created a Black feminist sociology together. They both pointed out that “domination rests on emotion, a desire for absolute control” (Madoo and Niebrugge 1998:169). Their point was that societal domination is not just about making a profit or otherwise increasing one’s financial status. Rather, there is an emotional factor within societal domination. Cooper (1892) provides an example by noting the extra expense paid by railroad companies in providing a separate car for People of Color, as discussed at the beginning of the chapter.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Web007rzSOI

Though Wells-Barnett was a journalist, she made contributions to sociological thought by way of her activism against lynching. She researched and published accounts of lynching that showed the out-of-control aggression of White Americans towards Blacks (Madoo and Niebrugge 1998). After examining the various excuses used by Southern Whites for their attacks on Blacks, Wells-Barnett ([1895] 2018) wrote that there would be no need for her research, “If the Southern people in defense of their lawlessness, would tell the truth and admit that colored men and women are lynched for almost any offense, from murder to a misdemeanor” (p. 11). The lynchings that Wells-Barnett documents are described in the song that Billie Holiday sings, “Strange Fruit” linked in Figure 3.18. If you want to learn more, read about Anna Julia Cooper and Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

These Black feminist founders of sociological thought planted the seeds for the emergence of influential sociological theory from the 1980s and 1990s, which centered on the experiences of Black and Indigenous women of color. Though the concept of intersectionality is most often attributed to critical race legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, within sociology Patricia Hill Collins (1948–present) is recognized for providing complex and detailed analyses of the concept. Her theorization of the outsider within perspective shows how Black women “have a clearer view of oppression than other groups” whose identities are different (1986:20). Collins (1986) details how Black women participate in social systems but not as insiders, given their oppression. Participating in a social system that oppresses them, Black women have a unique standpoint that offers more information. They can see more clearly how our social structures of race and gender work intersectionally.

Collins’s (1986) theory of interlocking oppressions points out philosophical foundations that underlie multiple systems of oppression. It is common in sociology to explain inequality in terms of race, class, or gender alone. Either you are Black or White, male or female, young or old, and so on. One group in each dichotomy has more power than the other. With some additional complexity, sociologists discuss issues of oppression related to race and class or age and gender, for example. Collins argues that these either/or additive approaches missed the point.

Instead, Collins explains that oppression exists as a matrix of domination, a concept which says that society has multiple interlocking levels of domination that stem from the societal configuration of race, class, and gender (Andersen and Collins 1992). Patriarchy and ableism work together to make disabled women and nonbinary people invisible. Structural racism, heteropatriarchy, and classism interlock to oppress transgender People of Color who don’t have much money. This Black feminist analysis sees the holistic experience of interlocking and simultaneous oppressions and challenges people to see wholeness instead of difference (Collins 1986).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSXh8-a8H4M

These same oppositional differences are seen in the work of Chicana theorist and activist Gloria Anzaldúa (1942–2004). Anzaldúa theorizes the idea of the borderlands, or la frontera (Figure 3.19). The borderlands is a terrain, both literal and imagined, where we live. Living in the borderlands involves the simultaneous occurrence of contradictions. Anzaldúa (1987) writes that when you live in the borderlands you are a “forerunner of a new race, half-and-half—both woman and man—neither—a new gender (p. 216). She uses various writing styles including poetry, as well as various languages to write her theory. In this way, she challenges the dominant way of composing scholarship. Her transitions between languages and dialects were groundbreaking. They served to question the dominance of certain languages (English) and ways of speaking (“proper” English).

Together these Black and Indigenous theorists of color advanced scholarly understandings of difference and oppression. Many of them also used nontraditional methods to articulate their ideas, often using personal experience or placing value on emotion. This contrasts with historical ways of doing theory that emphasized objectivity and reason. Objectivity refers to the idea of conducting research with no interference by aspects of the researcher’s identity or personal beliefs. Contemporary scholars believe it is impossible to ever be completely objective. Another similarity between these theorists is the links they made between composing scholarly work and doing activism out in the world. They worked to bridge the two and advocate for a reciprocal relationship so that what was happening in the world directly impacted scholarly work.

Critical Race Theory

To better understand race and racism, social scientists examine racial power dynamics in the United States and throughout the world. Sociologists have long understood race to be a social construct. Race is a product of social thought rather than a material or biological reality. Yes, people have different levels of melanin in their bodies, but that is as far as any biological notion of race goes. One sociological theory of race describes race as an ongoing, ever-evolving construction with historical and cultural roots (Omi and Winant 1986). The long-lasting economic inequality caused by slavery and systemic racism combines with all of the racial stereotypes circulating in media and popular thought to create our current racial formation.

Racial formation refers to the categories of race we currently have in this country and all of the meanings popularly attached to them. The United States counts race differently in different decades. In 1790, the census counted free White women and men, other free people, and slaves. In 2010, the categories expanded to include White, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Other, and Hispanic. By 2020, though the categories didn’t change much, people could select more than two options. These census changes help us to more accurately reflect our multiracial and diverse population (Marks and Rios-Vargas 2021).

While understanding the socially constructed nature of race is important, American social theorist Joe R. Feagin (2006) criticizes racial formation theory for failing to include an understanding of how slavery generated huge profits for White Americans, who then passed that money on to their future generations. Feagin’s view of systemic racism insists on understanding the long-lasting impacts of slavery and recognizing White-on-Black oppression as firmly embedded within US society. Feagin (2006) writes, “For a long period now, white oppression of Americans of color has been systemic—that is, it has been manifested in all societal institutions” (p. xiii). If you’d like to learn more, you can read about Joe R. Feagin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miVlHcdjaWM

You may have seen the words critical race theory on social media or in your local newspaper. Critical Race Theory (CRT) is the theory that systemic racism is embedded in US institutions, not just the behavior of individuals. Ibram X. Kendi describes Critical Race Theory in the 5.19 minute video in Figure 3.20. The NAACP defines it in more detail like this:

Critical race theory, or CRT, is an academic and legal framework that denotes that systemic racism is part of American society — from education and housing to employment and healthcare. Critical race theory recognizes that racism is more than the result of individual bias and prejudice. It is embedded in laws, policies and institutions that uphold and reproduce racial inequalities. According to CRT, societal issues like Black Americans’ higher mortality rate, outsized exposure to police violence, the school-to-prison pipeline, denial of affordable housing, and the rates of the death of Black women in childbirth are not unrelated anomalies (NAACP Legal Defense Fund 2023).

CRT emerged in the 1980s out of a concern by legal scholars of color that the measures installed by the civil rights movement to alleviate racial injustice were no longer addressing the problem or never did.

Critical race theorists take a systemic view of racism. They see racism not as a quirk within our society but as an everyday occurrence within many, if not all, parts of life (Delgado and Stefancic 2017). They raise questions about the law’s ability to address systemic racial inequality.

One discussion about CRT revolves around what to teach children in K-12 schools. Some White people worry that White children are being made to feel guilty for being White. However, this is a misunderstanding of the theory. It’s not about guilt. It’s about structural racism, the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice (Bailey et al 2017).

The American Sociological Association supports teaching CRT because understanding how race impacts inequality is fundamental to changing racist laws, policies and practices (ASA 2023). Advocates for racial justice affirm the importance of discussing race and racism with children in school settings. To learn more, check out this blog, “Critical Race Theory: ‘Diversity’ Is Not the Solution, Dismantling White Supremacy Is.”

Queer Theory

Queer theory is an interdisciplinary approach to sexuality and gender identities that identifies Western society’s rigid splitting of gender into male and female roles and questions how we have been taught to think about sexual orientation and gender (Figure 3.21). By calling their discipline queer, scholars reject the effects of labeling. Instead, they embraced the word queer and reclaimed it for their own purposes. The perspective highlights the need for more flexible and fluid notions of sexuality and gender that allow for change, negotiation, and freedom. One concrete example would be allowing individuals to write in their gender identity on forms or leave it blank.

French social theorist Michel Foucault (1978) traced the history of the concept of sexuality and saw that powerful forces encouraged its development as part of an effort to reveal and eliminate any deviant forms of sexual expression. Foucault’s work on sexuality raises many questions: Why are we asked to identify as a specific sexuality? Wouldn’t we be freer if sexuality wasn’t categorized (e.g., homosexual/ heterosexual)? Of course, many LGBTQIA+ activists would argue otherwise, given the power of self-identification and advocacy for rights and respect.

Another well-known queer theorist, Judith Butler, also critiqued categorizations, but her objections included gender identities. As with Foucault, she felt these categories were limiting. Butler is recognized among sociologists for developing the theory of the performativity of gender. This theory describes gender as a way of appearing to others through clothing, nonverbal communication, make-up, etc., instead of an inner feeling or identity. Thus, gender is a matter of learned performance and can be reconstructed (Wilchins 2004). In this approach, sociologists talk about “doing gender.” Like symbolic interactionists, they say gender expression is an intentional choice made in everyday interactions. This theory opens the doors for us to re-think what we want gender to mean or for us to do away with the concept of gender altogether and replace it with something else. Theorists who use queer theory strive to question the ways society perceives and experiences sex, gender, and sexuality, creating a new scholarly understanding.

Theories of Interdependence

As we discussed in Chapter 1, we are interdependent. We need each other to survive and thrive. How do sociologists understand this concept and apply it to understand the social world?

To answer that question, we need to start with our friends, the biologists. Like Simba and the pride in the circle of life, as described in The Lion King, biologists recognize that all life is interconnected. They refer to specific instances of this interdependence as ecosystems. An ecosystem is a geographic area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscapes, work together to form a bubble of life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXPGr9bJmG0

A tide pool is a tiny ecosystem, like the one shown in Figure 3.22. The pool contains seaweed which photosynthesizes and creates oxygen and plant matter. Tiny abalone eat the seaweed. Mussels cling to the rocks, filtering the ocean water and eating the small life the water contains. Sea anemones eat plankton and small fish. Sea stars eat the clams and mussels. A giant Pacific octopus tries to find its way back to the ocean. The whole ecosystem depends on the moon and the tides to be refreshed and restored. If you remove one part, the tiny ecosystem of the tide pool falls apart.

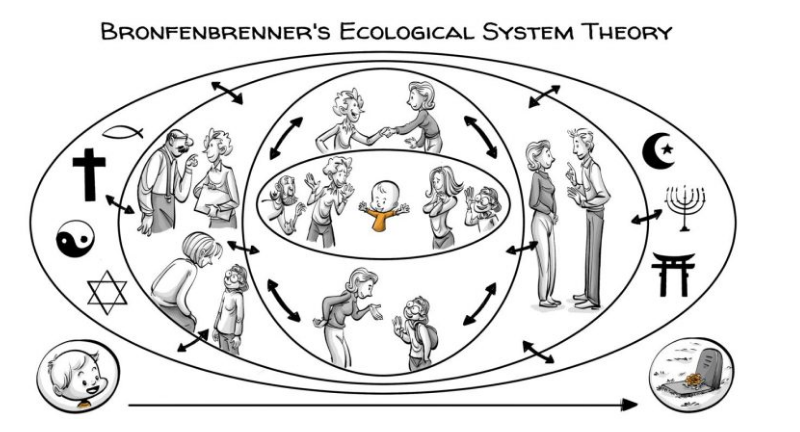

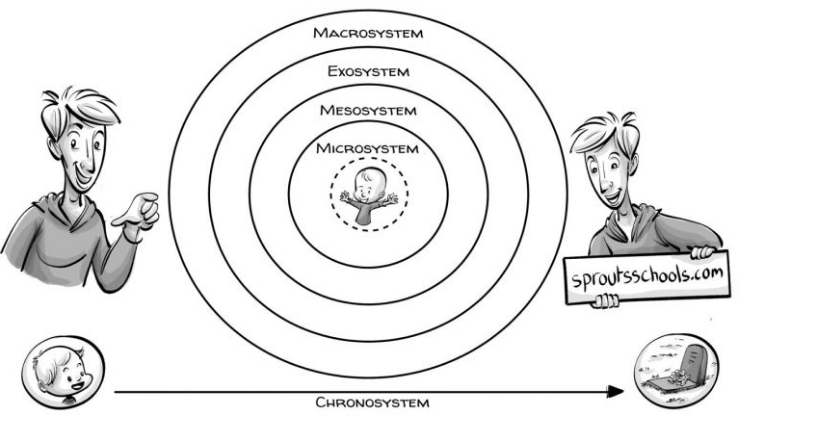

In the mid-1950s, social scientists began to apply this idea to human systems also. Russian-born American psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner proposed the ecological systems model to describe the social influences on individual life. The common understanding of poverty at that time was that people were poor because they made bad choices. Bronfenbrenner’s model suggested that outside influences contributed to poverty beyond the level of the individual. This sounds a lot like the sociological imagination from Chapter 1, doesn’t it? The following two diagrams and the associated video illustrate the concept (Figure 3.23 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory and Figure 3.24 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory with labels).

In the ecological system theory model, the social world contains layers, each with its own influence on a child. The system moves from the smallest level of the individual child to the microsystem of family, through growing layers until it reaches the macrosystem of institutions and society. The systems also change over the lifetime of the person, as represented by the chronosystem.

This early model of applying ecosystems to human behavior was very effective. When Bronfenbrenner presented this theory to Congress, they funded Head Start. This program provides free preschool to young children in high-poverty areas. For a more complete story, watch “Ecological System Theory [YouTube Video].”

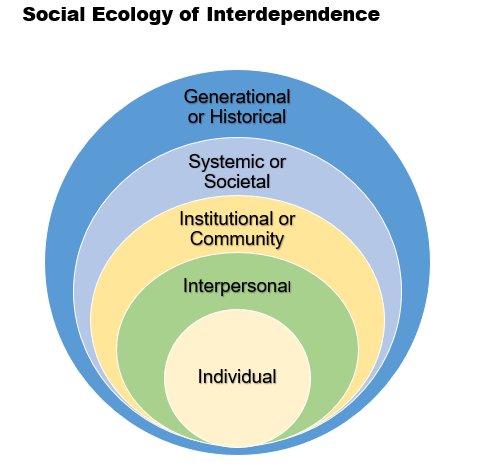

Sociologists have built on the social ecosystem model proposed by psychologists. An online search of wide-ranging topics from the root causes of health inequality, increasing economic equity for young Black men, or addressing bullying of LGBTQIA+ students finds many variations of this model.

The labels of the circles vary, depending on the problem researchers and activists are trying to describe. However, all of the social ecology models move from the personal and individual out through the layers to systemic or structural causes of social problems.

The model in Figure 3.25 is useful in understanding the various levels of society by showing how individual, community and institutional actions are connected. Sociologists call this a social structure, the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups through the relationship between institutions (e.g., economy, politics, religion) and social practices (e.g., behaviors, norms, and values). Seeing these levels clearly also helps us see the harm that can happen at each level, as well as the healing that is possible. This model, and the table in Figure 3.26 that describes it, will be used throughout the book to anchor our discussions where social problems occur in society. The social ecological systems model also helps us link individual agency and collective action as we work to solve interdependent social problems.

The table in Figure 3.26 provides more detail about each level. Don’t worry if you don’t capture every detail. You will see this illustration often, so you have time to make sense of it.

| Level | Description | Harm | Healing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | This level reflects the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of an individual. | Prejudice, internalized homophobia, or implicit bias causes harm. | Recognizing and changing unconscious assumptions or internalized hatred allows healing. |

| Interpersonal | This level reflects interactions between people, in families and in groups. | Microaggressions, name calling, and violence against individuals or groups causes harm. | Practicing anti-racist behaviors or stepping forward/stepping back to center the experiences of marginalized people allows healing. |

| Community/Institutions | This level reflects institutions like school, work, church, or government. It can also reflect your neighborhood, city, or state. | Laws, policies, or implementation of those policies cause harm. | Changes in laws, policies or practices allows healing. |

| Systemic or Societal | This level reflects structures or culture that surround the institutions. | A hierarchy of groups or pervasive beliefs, attitudes, or actions that one group is superior to another causes harm. | Focusing on institutionalizing equitable practices and promoting cultural change at all levels of society allows healing. |

| Generational or Historical | This level reflects time – the past structures of society or behaviors that are passed from parents to children. | Trauma, oppression, and violence of the past may cause harm. | Recognizing the historical roots of oppression and repairing the harm, or healing intergenerational trauma allows healing. |

Each of these theoretical approaches explains society through a different lens. Depending on your questions, one lens may be more useful than another.

Unpacking Oppression, Locating Justice

In this chapter, you met many sociologists, social scientists, and activists. You may have noticed that many of these people have links with biographies or details about their theories. That’s a lot of links!

We added these links because we know that a scientist’s social location impacts their work. Karl Marx was poor. That might have influenced how he explained capitalism. Gloria Anzaldúa was Chicana, and she worked to explain her experience using the concept of borderlands.

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and locate justice:

Sociologists work from their particular social location. Who they are, the historical period they live in, and the issues they experience become sources of their sociological work. Throughout this book, you will notice that we highlight sociologists and activists so that you know who is creating the knowledge you are learning. This activity will help you practice learning more about sociologists and social location.

Instructions

- Pick a sociologist that you want to understand from this chapter or anywhere in the book.

- Learn more about them—were they rich, poor, or somewhere in the middle? Did they identify as White or some other race or ethnicity? What was their gender identity? How many elements of social location can you find?

- Identify their Historical or Social Context: What social problems or historical events were they reacting to?

- Key Concept: What essential idea or key concept did they contribute to sociology?

- Reflect: How did the social problems of the time and the social location of the sociologist interact to produce their social theory?

Licenses and Attributions for Modern and Emerging Social Theories

Open Content, Original

“Modern and Emerging Social Theories” by Kelly Stolz and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.25. “Social Ecosystem Model” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.26. “Table of the Social Ecosystem Model: Harm and Healing” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Queer Theory” definition from Introduction to Sociology 2e by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns, Openstax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Feminist Theory” and “Social Structure” definition is adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Feminist and Intersectionality” is adapted from “Reading: Feminist Theory” by Lumen Learning, Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Edited to simplify reading level.

“Feminist Theory” is adapted from “An Introduction to Sociology” by William Little and Ron McGivern, Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Some components borrowed.

Figure 3.16. “Photo” of Dorothy Smith by Schmendrick2112, Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 3.21. “Two Men Sitting Down” by Jean-Baptiste Burbaud is licensed under the Pexels License.

Figure 3.22. “Giant Pacific octopus spotting at Yaquina Head tide pools” by Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.23. “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological System Theory” from “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems” by Jonas Koblin, Sprouts Schools is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 3.24. “Give It a Try” from “Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems” by Jonas Koblin, Sprouts Schools is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.15. “Modern Sociologists” by Michaela Willi Hooper and Kimberly Puttman, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is all rights reserved due to photo restrictions. Please contact Open Oregon Educational Resources before re-sharing. Open images: “C. Wright Mills” by Institute for Policy Studies is licensed under CC BY 2.0, “Joe Feagin” by Louwanda is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, “Angela Davis” by Columbia GSAPP is licensed under CC BY 2.0, “Gloria Anzaldua” by K. Kendall is licensed under CC BY 2.0, “Patricia Hill Collins” by Valter Campanato/Agência Brasil is licensed under CC BY BR 3.0, “Judith Butler” by University of California Berkeley is Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

Figure 3.17. “Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw: What is Intersectional Feminism?” by Omega Institute for Holistics Studies is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.18. “Billie Holiday- Strange Fruit- HD” by prokoman1 is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.19. “To Live in the Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldua” performed by Nancy Rodriguez, The Young Center is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.20. “What Critical Race Theory Actually Is — and Isn’t” by NowThis News is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

the concept that people rely on each other to survive and thrive

the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand individuals, groups, and institutions through data collection and analysis.

a biological categorization based on characteristics that distinguish between female and male based on primary sex characteristics present at birth.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

overlapping social identities produce unique inequities that influence the lives of people and groups.

an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others

extra-judical killings in which an individual or a mob kidnaps, tortures, and kills persons suspected of crime or social transgressions

the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care and criminal justice

the irrational fear of or prejudice against individuals who are or are perceived to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual people.

an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper.

the unrealistic idea of conducting research with no interference by aspects of the researcher’s identity or personal beliefs

the unequal treatment of an individual or group based on their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex)

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a response to racism that changes social systems to reduce racial inequities and address the social and interpersonal conditions caused by racial inequities.

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attractions toward another person

a person who does not conform to norms about sexuality and gender (particularly the ones that say that being straight is the human default and that gender and sexuality are hardwired, binary, and fixed rather than socially constructed, infinite, and fluid).

one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither – how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One's gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and more.

the external appearance of one’s gender identity, usually expressed through behavior, clothing, body characteristics, or voice, and which may or may not conform to socially defined behaviors and characteristics typically associated with being either masculine or feminine.

an interdisciplinary approach to sexuality and gender studies that identifies Western society’s rigid splitting of gender into male and female roles and questions the manner in which we have been taught to think about sexual orientation and gender.

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.

the state of everyone having what they need, even if it means that some need to be given more to get there.

a personal or institutional system of beliefs, practices, and values relating to the cosmos and supernatural.

the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change, free will, or self-determination.

the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision

a person who is supporting an antiracist policy through their actions or expressing an antiracist idea.

a person (or group) response to a deeply distressing or disturbing event that overwhelms one's ability to cope, causes feelings of helplessness, diminishes self esteem and the ability to feel a full range of emotions and experiences.

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

an economic system based on private ownership and the production of profit.

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion.