5.4 Education, Poverty, and Wealth

Kimberly Puttman

One of the deepest causes of the social problem of education is inequality in school district funding. That’s important, but we can also ask a different question: Can education make you rich? Or as sociologists might ask: Is education a solution to the social problem of poverty?

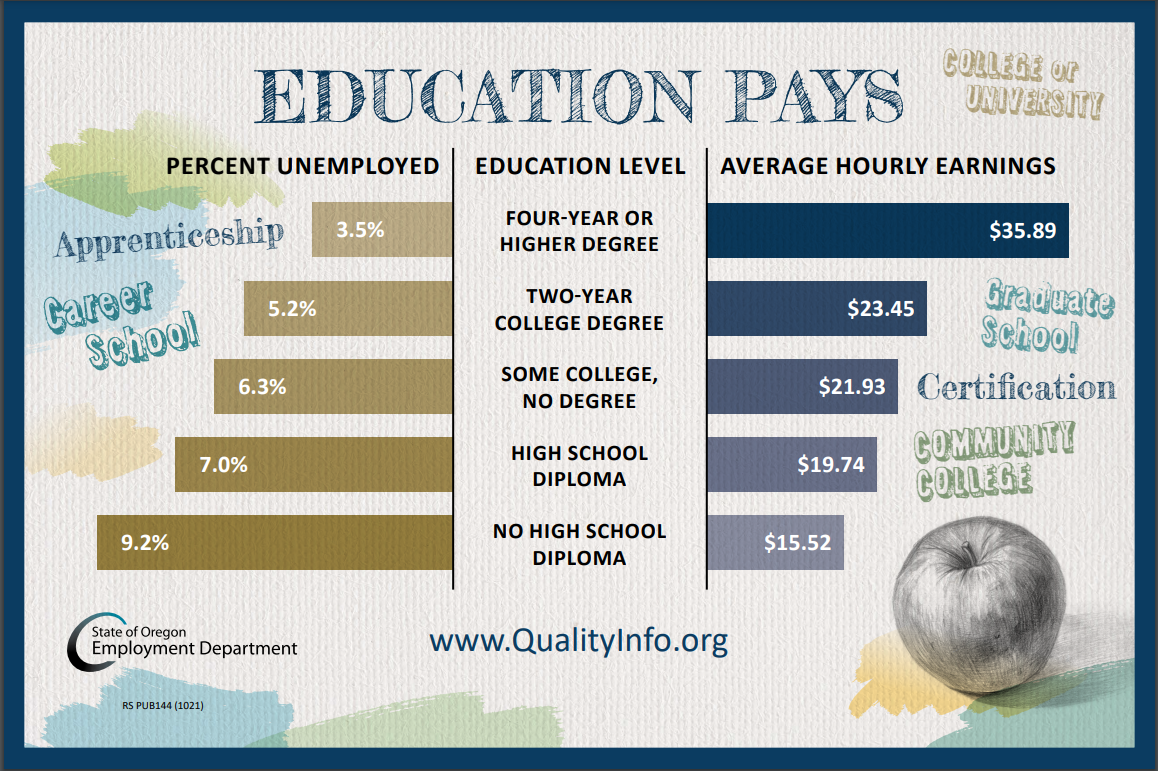

You may have seen the following chart as you were deciding to go to college (Figure 5.19):

This chart is commonly used in Oregon high schools and state unemployment offices to show that it pays to get a college degree. People with a four-year degree or higher experience less unemployment and significantly higher hourly earnings than people with a high school diploma. Of course, these charts conclude that everyone should get the most education possible so they can make enough to buy houses and care for their families. Is this the whole picture, though? Sociologists would say no, for several reasons.

First, this chart hides alternate ways of training and education. Where are the plumbers and the electricians who attend training other than college? Where are the medical transcriptionists, massage therapists, and other health professionals who may not attend college and yet are highly trained professionals? Perhaps you know a social media influencer or an IT professional who didn’t graduate from college but still earns a lot of money.

Second, when we look at unemployment data, we only look at people who are eligible for unemployment, not all people, not even all who would be in the workforce if they could find work. This data then under-reports the number of people who may be looking for work but are no longer eligible for state or federal unemployment benefits. Even though definitions of who can be considered unemployed have expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall statistics don’t tell a complete picture. What about cosmetologists, hairdressers, tattoo artists, musicians, and other creative workers who earn incomes often through self-employment and are not counted in unemployment statistics?

Finally, these statistics don’t take gender, race, age, ability, or other social locations into account. Let’s look more deeply at economics, education, and class.

Individual Improvement versus Class Improvement

A common saying for those who work to end poverty for families is that there are two ways out of poverty—education and savings. Is this really true for all families?

Sociologists differentiate between social mobility and structural mobility. Social mobility is the ability of a person or a family to change economic groups in their society. When we consider the dream of immigrants to the United States in the past and today, many say that their American dream is to work hard so that their children can have a better life than they do. When you consider your own family history, you may notice you have more education than your grandparents or great-grandparents. Over time, individuals and families can get richer or poorer, moving between social classes. Education can contribute to social mobility of an individual.

Structural mobility is the ability of an entire class of people to become more wealthy or less wealthy. The efforts of the United Nations and other world service organizations to end extreme poverty would fall into the case of structural mobility. In general, industrialization has resulted in a higher standard of living for many people. Many people now have electricity and indoor plumbing, indicating some amount of upward structural mobility. However, global literacy and other educational measures are higher than they have ever been worldwide. If education was truly the only cause of structural mobility, we would see a reduction in poverty, and we don’t (Hanauer 2019).

Correlation and Causation

To explain this contradiction between education and structural mobility, we need to use two sociological concepts: correlation and causation. Causation in science is when a change in one variable causes a change in the second variable. Correlation, on the other hand, occurs when a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable, but does not cause the change to happen.

For example, sociologists might measure how many churches and grocery stores there are. They might see that where there are more churches, there are also more grocery stores. They might conclude that because many churches host potlucks, dinners, and soup kitchens, more groceries are needed. Alternatively, they might conclude that well-fed people go to church more often. However, there is a third variable at work—population. The more people live in a particular location, the more built environment there is likely to be, including schools, churches, grocery stores, and libraries. Population size drives causation at this point, even though the number of churches and grocery stores is correlated.

As we apply these concepts to education, our essential question deepens: To what extent do changes in education levels cause social or structural mobility?

Models of Education, Wealth, and Poverty

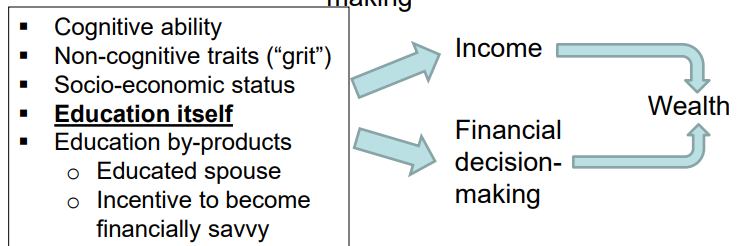

To answer this question, we look at this model developed by economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. They propose the following relationship between education and wealth in Figure 5.20:

This model has a lot going on, so let’s break it down together. In the first column, we see characteristics that influence further steps in the model. These characteristics include your smartness, persistence, socioeconomic class, education, and the idea that you are likely to marry a similarly educated spouse. Not listed in the model is the idea that people from higher socioeconomic classes expect to live longer because they have access to good medical care, so they have some incentive to do financial planning (and extra wealth in the first place so that they can save).

All of these factors increase income and lead to better financial decision-making. These two factors influence the acquisition of wealth, the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns. This could include land, savings, stocks, buildings, or businesses, among other examples. This study concludes that it’s not education that directly leads to wealth. Rather, wealthy people are more likely to have more access to education and attain higher educational outcomes.

Global models, on the other hand, paint a slightly different picture. Let’s look at what can change.

Educating women tends to lead to higher age at marriage and greater maternal health. Because more girls between the ages of 15 and 19 die from pregnancy complications than any other cause of death, increasing the age of marriage, and thus the age of first pregnancy, reduces mother and infant mortality. If all women had a primary education, maternal deaths would decrease by 66% (UNESCO 2013:7).

Educated women also make more money. With more skills, a woman can look for higher-paying work, reducing poverty in her family and increasing economic stability. When women are educated, economies can grow. Education helps to narrow the gender pay gap for women because women can get more skilled jobs if they have the training. Education also increases the productivity of a country, leading to economic growth (UNESCO 2013).

Third, when women make more money, they tend to spend that money on food and education for their children, strengthening the health of their entire families. This reduces malnutrition and death from hunger. If all mothers had secondary education, 26% of all children stunted from malnutrition would be well nourished (UNESCO 2013:13).

Finally, educating women supports the overall health of entire communities because education encourages women’s leadership where they live (Wodon et al. 2018; Borgen Project 2018). It also improves community resilience because education promotes tolerance and trust of people different from you (UNESCO 2013). If you would like to listen to this story, watch Educate Women and Save the World [Streaming Video], a 4:12 minute TED talk from student Dorsa Esmaeili. She is of Iranian descent and speaks from a school in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Education is one way to influence a social problem, whether your family got more economically stable because your parents were first-generation college students or your mom got a better job because she became a nurse. However, it’s not the whole answer. When you consider whether you should study for your next test, take the next class, or even go to college, the money you might make can only be part of the reason.

Licenses and Attributions for Education Poverty and Wealth

Open Content, Original

“Education Poverty and Wealth” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Correlation” definition from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.21. “Girls’ classroom in Afghanistan” by Alejandro Chicheri, World Food Programme is in the Public Domain; “India – Second Chance Education and Vocational Learning (SCE) Programme” by UN Women Asia and the Pacific is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; “Primary school students with devices for math” by Talento Tec is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.19. “Oregon Education Pays” from “Workforce and Economic Research Update OED Advisory Council (2/4/2022)” (slide 11) by QualityInfo.org, State of Oregon Employment Department is included under fair use.

Figure 5.20. “Correlation vs. Causation: Three Theories. Theory Three” (slide 25) from “Education and Wealth: Correlation Is Not Causation” by William R. Emmons, Center for Household Financial Stability, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis is included under fair use.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

an individual’s or group’s (e.g., family) movement through the class hierarchy due to changes in income, occupation, or wealth.

a shift in hierarchical position of an entire class of individuals over time in society.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

when a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable but does not necessarily indicate causation

a change in one variable causes a change in another variable

the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns

the money a person earns from work or investments

When a person’s body ceases to function

the number of deaths in a given time or place