11.2 The Social Problem of Drug Use and Misuse

Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman

There are many ways to construct drug use and addiction as a social problem. Drug use is simply the imbibing of substances, which can happen without addiction or physical dependence but may lead to those outcomes. There is nothing inherently wrong with drug use. On the other hand, addiction is the chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2020). But it’s not just addiction or illicit drug use that is the social problem. The unequal impact of drug use on families and communities is the social problem. This chapter will not discuss drug use as inherently bad.

Instead, we will examine this social problem based on some of the characteristics of a social problem from Chapter 1. As the stories in section 11.1 illustrate, the opioid epidemic impacts everyone, from individuals to families, hospitals, workplaces, and governments. It goes beyond the experience of one individual.

Secondly, in our exploration of drug use and misuse, we see social construction at work. You may notice that throughout this chapter, we use the word cannabis to describe the drug that is commonly known as marijuana or weed. The common word marijuana is racist. It reflects a racist past. More specifically, the United States experienced an increase in Mexican immigration after the 1910 Mexican War of Independence. Some immigrants used the herb mariguano for casual smoking. Although the immigrants were important in providing needed agricultural labor, the increase in immigration raised xenophobic fears.

Mexican immigrants were often blamed for property crimes and sexual misconduct. White people in power conveniently blamed the use of marijuana for this. “One Texas state legislator proclaimed on the senate floor: “All Mexicans are crazy and this stuff [cannabis] is what makes them crazy” (Ghelani 2020:7). In 1937, Harry Ainsliger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics testified before Congress saying, “marihuana is an addictive drug which produces insanity, criminality, and death” (Ghelani 2020:8). Associating the use of cannabis with Mexican immigrants by naming it marijuana was a way to assert power and control over a particular ethnic group. This is using language as a social construction. To resist this oppression, we will use the word cannabis instead of the word marijuana in this chapter, except when we are quoting from other people.

In addition, we remember that a social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality. This point is particularly important when we discuss drug use and harmful drug use. People of all races use drugs at the same rate. However, People of Color are likely to be arrested and jailed for drug offenses. White people are more likely to be seen as needing medical intervention, and therefore they are more likely to receive treatment. More specifically:

Although Black Americans are no more likely than Whites to use illicit drugs, they are 6–10 times more likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses. (Netherland and Hansen 2017)

This racialized response to harmful drug use is a deep source of inequality, a key component of a social problem.

Finally, we recall that social problems must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action. In this case, citizens, lawmakers, health care workers, community advocates, and the individuals themselves must act to address the social problem. We’ll look at various solutions in more detail in Recovery is Social Justice.

Harmful Drug Use

Drug use can be a problem for anyone, but it is people’s different social locations that determine how harmful the drug use will be for themselves and for their family, friends, and community. Harmful drug use occurs when it negatively impacts a person’s health, livelihood, family, freedom, or other important aspects of their life.

One of the dominant approaches to understanding addiction involves looking solely at how a person’s brain is affected by drug use. Another popular approach focuses on the psychology of the user and the chemical traits of the substance. Both approaches ignore social issues such as poverty, racism, and sexism that increase the harmfulness of drug use for certain individuals, populations, and neighborhoods. Incarceration, disease (such as HIV), other negative health impacts, job loss, and family disruption are examples of harms associated with drug use that are more or less likely to occur depending on one’s social location.

In contrast, the sociological perspective focuses on the social determinants of harmful drug use. This perspective avoids blaming the individual and making them responsible for getting the proper treatment and resources to fix issues caused by social inequality and oppression. A sociological lens can help us see how social structures of oppression can change the outcomes of harmful drug use depending on the social location of an individual (Friedman 2002).

Problematic Drug Use

Social scientists point out that a person’s socioeconomic class may impact whether they can continue to work or go to school while using substances (Zinberg 1984; Singer and Page 2014; Friedman 2002). For example, White middle-class users of opioids, like heroin, are less likely to get arrested or go to jail. Therefore they can more often keep their jobs and still earn money.

Racism in our society creates differences in how White people and People of Color are treated when they use drugs. White people are more likely to be seen as people experiencing a medical condition. Therefore, they need drug treatment to recover. Black, Brown, and Indigenous people are more likely to be seen as criminals. They are more likely to be arrested and put in jail than receive treatment This chapter will discuss how racist social structures shape the experiences of problematic drug use.

A problem in deciding how to think about and deal with drugs is the distinction between legal drugs and illegal drugs. It makes sense to assume that illegal drugs should be the ones that are the most dangerous and cause the most physical and social harm, but research shows this is not the case.

Rather, alcohol and tobacco cause the most harm even though they are legal. As Kleiman and his research team note about alcohol:

When we read that one in twelve adults suffers from a substance abuse disorder or that 8 million children are living with an addicted parent, it is important to remember that alcohol abuse drives those numbers to a much greater extent than does dependence on illegal drugs. (2011:xviii)

According to the CDC, cigarette smoking kills 480,000 people due to complications from smoking or secondhand smoke (CDC 2022). Alcohol use prematurely kills 140,000 people per year in the US. These deaths are caused by physical damage related to long-term use. They are also caused by drinking too much alcohol in a short period of time. DUI fatalities are one example of this premature death. The rate of premature death is much higher for legal drugs than illegal ones.

Dependence

Substances that we consider drugs interact with our bodies in different ways. Drugs are often grouped by the kinds of physical effects they have. Some drugs, called depressants, slow down the central nervous system. Hallucinogens cause people to hallucinate, to see, hear, or experience things that are not physically real. Narcotics, derived from natural or synthetic ingredients, are effective at relieving pain, but they depress the nervous system. They are also highly physically addictive. Stimulants speed up the nervous system, potentially causing alertness, euphoria, or anxiety. Finally, cannabis may create euphoria, hunger, and relaxation and dull the sense of time and space.

Important distinctions exist between addiction, physical dependence, and drug use. These three are not mutually exclusive, but they differ from each other in significant ways. Addiction is often associated with a mental health diagnosis such as substance use disorder. Rather than using the diagnosis of addiction, health professionals now use the language of substance use disorder (SUD), which is a condition in which there is uncontrolled use of a substance despite harmful consequences. People with SUD have an intense focus on using a certain substance(s), such as alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs, to the point where the person’s ability to function in day-to-day life becomes impaired (Saxon 2023). Physical dependence means that the body has built up a tolerance to the drug and that one must take the substance in order to not feel ill. Drug use is just that—the intake of a substance that produces a change in your body. This can happen with or without addiction or physical dependence.

Licenses and Attributions for Drug Use and Addiction as a Social Problem

Open Content, Original

“Drug Use and Addiction as a Social Problem” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Problematic Drug Use” (2nd paragraph) is adapted from “Drugs and Drug Use Today” from Social Problems: Continuity and Change by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications: Lightly edited for clarity and updated statistics.

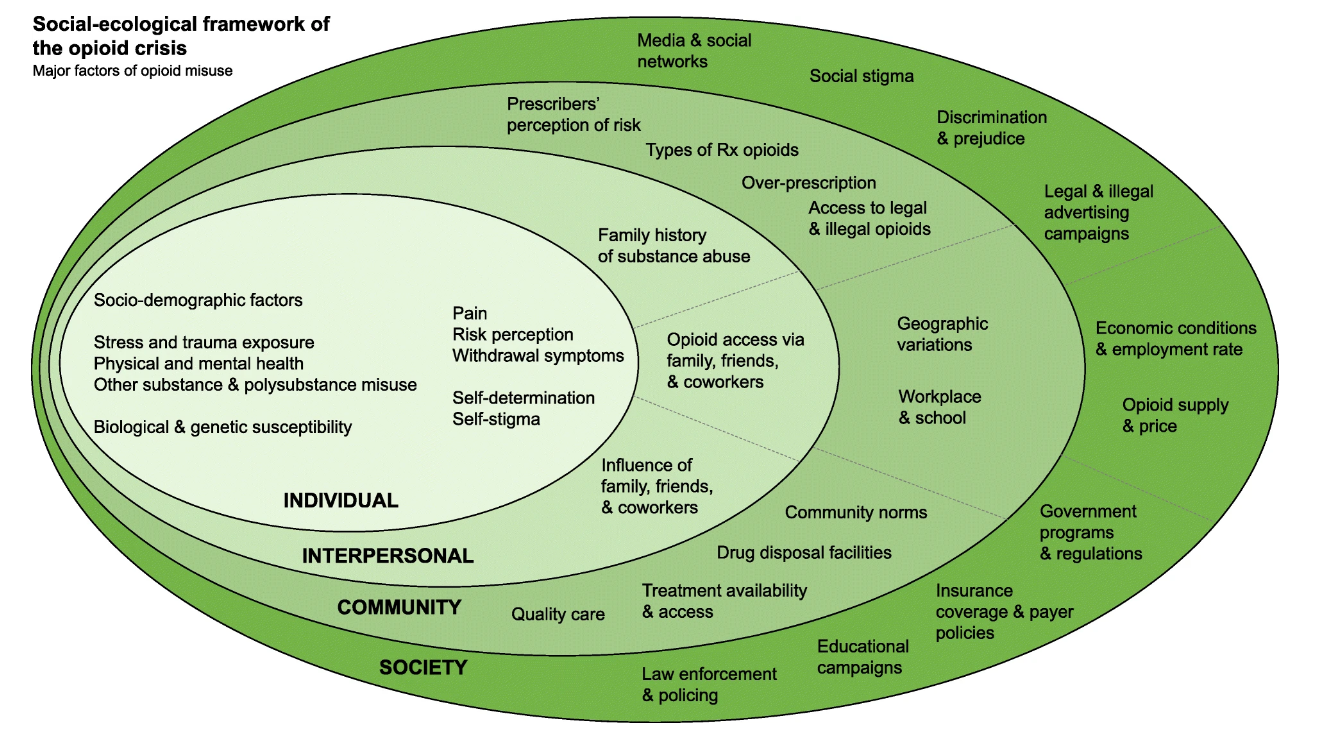

Figure 11.2. “The Social Ecological Framework of the Opioid Crisis” from “The opioid crisis: a contextual, social-ecological framework” by Mohammad S. Jalali, Michael Botticelli, Rachael C. Hwang, Howard K. Koh & R. Kathryn McHugh, Health Research Policy and Systems is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.3a. “Photo” by Charles Etoroma is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 11.3b. “Photo” by Fred Moon is licensed under the Unsplash License.

a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

shared understandings that are jointly accepted by large numbers of people in a society or social group

a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

When a person’s body ceases to function

a person’s drug use negatively impacts their health, their livelihood, their family, their freedom, or any other aspect of their life that they deem important

the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.