12.4 Mental Health: Models and Treatments

Kathryn Burrows

In this section, we explore the different models of mental health and mental illness. These models come to us from different academic disciplines—psychology, psychiatry, and sociology. All three have something to offer to help us understand mental health and mental illness.

Medical and Psychological Models of Mental Health and Mental Illness

The dominant models of mental illness are biological, medical, and psychological, and so are important to learn about even in a sociology course! Cultural views and beliefs about mental illness have varied enormously throughout history. For example, ancient humans once believed that mental illness was caused by the influence of evil spirits over the afflicted person. Accordingly, treatments back then involved removing part of the patient’s skull to allow the demon to escape. Later, during the Middle Ages, mental illness was thought to be connected to the moon (hence the term lunacy). Another common belief was that a person with mental illness was being punished by God.

Fortunately, we’ve come a long way since then. However, scientists are still struggling to pinpoint exactly what causes mental illness. Most people, however, agree that mental illness can be influenced by a variety of things, including biological factors, personal history and upbringing, and lifestyle. To help provide a framework for understanding these potential causes, experts have developed a number of different models, which we’ll explore here.

Biological model

The biological model of mental illness approaches mental health in much the same way a doctor would approach a sick or injured patient. They look for problems or irregularities in the body that are causing the symptoms. Adherents of the medical model believe that mental illness is primarily caused by biological factors such as abnormal brain chemistry or genetic predisposition (McLeod 2023).

Medical model

The medical model of mental illness has proven to be true in many cases. For example, depression has long been linked to deficiencies in certain neurotransmitters (a chemical substance that is released at the end of a nerve fiber), and schizophrenia has been shown to run in families. Science like this forms the basis of psychopharmacology, which is the treatment of mental illness with medication that adjusts the level of neurotransmitters present in the brain. Researchers still do not know what turns on or off the brain/chromosome structures. The result is an impairment of a person’s overall level of functioning. However, critics of the medical model believe that it is too simple because it ignores important social factors in a person’s life.

Psychological model

As you might expect, in the psychological model of mental illness, psychologists look at psychological factors to explain and treat mental illness. For example, they look at attachment theory, which is a theory that examines how you relate to other people. In fact, there are over 500 different psychological models of therapy—there is a right model for everybody, and a psychologist’s or therapist’s job is to figure out which of those models works for which patient. Of course, psychologists have preferences and skill sets—no psychologist can practice 500 forms of psychotherapy. If you’d like to learn more about how psychotherapy is helping people with schizophrenia you can read Talk Therapies Take On a Vital Role in Treating Schizophrenia.

Sociological Approaches to Mental Illness

The previous models focus on biology, medicine and psychology. However, as sociologists, we know that social factors matter. Remember the Social Determinants of Health from Chapter 10? They apply also to mental health. The social determinants of health help us to explain why mental illness is also a social problem. Let’s look more deeply at sociological theories of mental health.

Functionalist

Functionalist sociologists begin to layer social approaches to medical and psychological models. Functionalists look at the function that mental illness and mental health play in society. They look at how mental health functions in a person’s life. To this end, they developed psychosocial and biopsychosocial models of mental illness.

One functionalist model of mental illness is called the psychosocial model of mental illness. The psychosocial approach focuses on how individuals interact with and adapt to their environment. Specific factors of interest might include a person’s relationships, past trauma, economic situation, outlook on life, and religious beliefs.

For example, stress—both good and bad—can affect your mental health. Social scientists pay attention to where these stressful areas are. In fact, starting a new job is in the top three stressful things—but most people are happy to start new jobs. Happiness aside, the new expectations, roles, and attitudes you find at your new workplace cause stress. Of course, negative things can also cause stress, and psychologists help people develop resilience against this sort of stress so they can successfully navigate the stressful situation.

Another thing psychologists take into account are your social roles. Having conflicting social roles—such as being a parent during COVID-19 and having a full-time job, is a role conflict that can cause stress. There are several kinds of role strain, situations caused by higher-than-expected demands placed on an individual performing a specific role that leads to difficulty or stress. For example, being a student can take up too much time according to your boss at work.

As the name implies, the psychosocial model focuses on the importance of psychological and social factors in informing a person’s mental health. Rather than looking to a person’s brain for clues, a proponent of the psychosocial model of mental illness might look to a patient’s personal history, attitude, beliefs, and life circumstances to better understand their mental illness.

But the psychosocial model is also limited because it doesn’t take biological or genetic factors into account. To address this, sociologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists have developed the biopsychosocial model of mental illness, which addresses the idea that mental health problems are caused by a combination of biological, sociological, and psychological features.

For example, it can be true that a patient has a biological disposition to mental illness and has experienced trauma that is causing or exacerbating their symptoms. Similarly, many patients have discovered that a combination of psychotropic medication and talk therapy helps address their mental health issues. In fact, many mental health care providers integrate both approaches into a more holistic framework called the biopsychosocial model.

Conflict

From Chapter 3 you will remember that sociologists who use conflict theory look at money and power to explain social inequality. When we look at inequality in mental health, as in the section Mental Health and Social Location, our approach is grounded in conflict theory.

We have an example of this approach to mental health in section Class Issues in Mental Health Treatment. If you look again at this section, you will notice that it is a conflict approach because it ties social class and wealth to rates of mental illness. In essence, The Chicago Schizophrenia Study found that people from poorer neighborhoods were more likely to develop schizophrenia than were people from middle-class neighborhoods. While Faris and Dunham had differing approaches to explain why this might be the case, the fact that poverty is linked to a health outcome is a classic conflict theory approach to mental illness.

Symbolic Interactionist

Mental illness impacts individuals, so why do sociologists, who study groups, research it? Michaels MacDonald, historian of psychiatry, observed, “is the most solitary of afflictions to the people who experience it; but it is the most social of maladies to those who observe its effects” (1981:1). Mental illness has social and cultural dimensions which compel sociological interest.

Psychiatry generally focuses on the suffering individual while sociologists study the social aspects and implications of an individual’s mental disturbance on friends, family, community, and society. Sociologists ask questions like:

- How can we define and draw boundaries around mental illness and distinguish it from eccentricity or mere idiosyncrasy?

- Who determines what is “normal” difference and what is pathological?

- Who has the privilege to make such decisions? Why? Do such things vary across time and cross-culturally?

- How have societies responded to the presence of those who do not seem to share our commonsense notions of reality?

As part of the answer to these questions, the social construction theory of mental illness states that mental illnesses, mental health, normality, and abnormality are all social constructions and are not based in biological reality. One socially constructed concept is the idea of what is normal. People in power say that normal is being happy and productive. If you are not these things, you are deemed “abnormal” or “sick.” The National Alliance for Mental Illness, or NAMI, challenges this idea and argues that people with mental illnesses are indeed “normal,” although they may be different. Differences are to be celebrated, not labeled as dangerous or damaged.

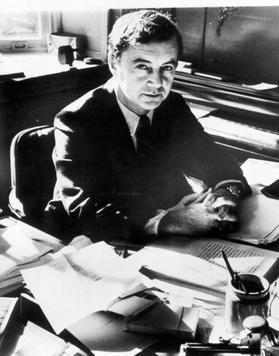

At the same time, mental illness has profoundly disruptive effects on individual lives and on the social order we all take for granted. Erving Goffman (Figure 12.19), whose mid-twentieth century writings still constitute some of the most provocative and profound sociological meditations on the subject, is perhaps best known for his searing critique of mental hospitals as total institutions.

Accepting, then, that there is such a thing as mental illness, a whole series of further questions then arise: Does the incidence and prevalence of mental illness vary by class, by age, by gender, by race, by ethnicity, and other social locations? Do these social variables affect how mental illness is reacted to and socially managed? What are the costs of such episodes of mental disturbance to individuals, families, and society, and how are those costs distributed?

How have societies characteristically responded to mental illness, and what institutions have they constructed to contain and perhaps cure it? What changes in these responses have occurred over time, and what accounts for these changes? One could go on, but the vital importance of a sociological perspective on mental illness should by now be apparent.

From the late nineteen-sixties through the nineteen-eighties, the intellectual distance and even hostility between sociologists and psychiatrists often seemed to be growing. Within five years of the appearance of Goffman’s groundbreaking book Asylums, the California sociologist Thomas Scheff had authored a more radical assault on psychiatry. Scheff dismissed the medical model of mental illness altogether and attempted to replace it with a societal reaction model, where mental patients were portrayed as victims—victims, most obviously, of psychiatrists (Scheff 1966).

Noting that despite centuries of effort, “there is no rigorous knowledge of the cause, cure, or even the symptoms of functional mental disorders,” argued that we would be better off adopting “a [sociological] theory of mental disorder in which psychiatric symptoms are considered to be labeled violations of social norms, and stable ‘mental illness’ to be a social role.” And “societal reaction [not internal pathology] is usually the most important determinant of entry into that role” (Scheff 1966:25).

During the 1960s and 1970s, the societal reaction theory of deviance enjoyed broad popularity and acceptance among many sociologists. Scheff’s was one of the principal works in that tradition. In the face of an avalanche of well-founded objections, Scheff was eventually forced to back away from many of his more extreme positions. By the time the third edition of his book appeared (Scheff 1999), most of its bolder ideas had been quietly abandoned. Labeling and stigmatization of the mentally ill have remained important subjects for sociologists. This stigmatization of illness is when shame or disgrace is aimed at a person with a physical or mental illness or condition. The idea of stigmatization is powerful, even if few would now argue that they have the significance once attributed to them.

Though the labeling theorists’ skeptical claims have been sharply curtailed, much of the sociological work on mental illness has retained its critical edge. Four major inter-related changes have occurred in the psychiatric sector in the past half-century.

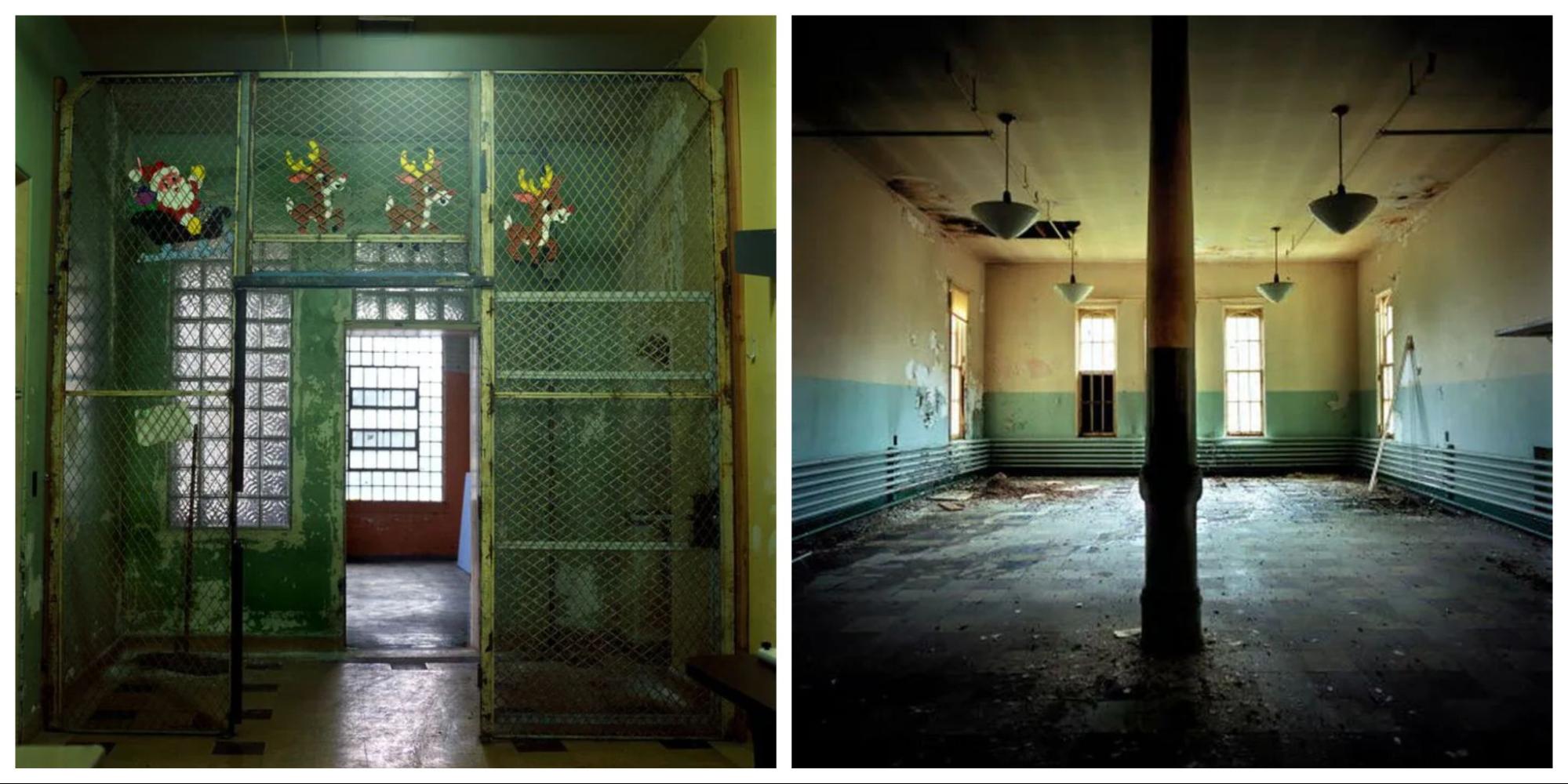

The first change is the progressive abandonment of the prior commitment to hospitalization for patients for life when they have serious mental illness. The second change is the rundown of the state hospital sector. We see changes in how patients are institutionalized in the set of photos from 12.20 to 12.23. As you look at these pictures, consider how mental illness and mental illness treatment are socially constructed over time.

Deinstitutionalization, for example, was initially presented as a grand reform, ironically just as the mental hospital had originally been. From the mid-1970s, however, a more skeptical set of perspectives emerged. Psychiatrists had assumed that the new generation of antipsychotic drugs had been the main drivers of the expulsion of state hospital patients. In reality, it was a political and economic decision by the federal government to close mental hospitals because they were expensive and overcrowded. Also, there was a move toward community mental health, which provides a patient-centered approach, but these services were not sufficiently funded. Also, there are not enough beds in current hospitals and psychiatric wards for the people who really need them.

Unfortunately, deinstitutionalization had several unintended consequences, including a rise in houselessness (Mechanic and Rochfort 1990). Another unintended consequence is that the prison system became a de facto asylum system. Approximately half of current prison and jail inmates experience a mental illness. However, treatment there is irregular and insufficient (Bronson and Berzofsky 2017). If you want to know more, please watch this 54-minute video, The New Asylums [Streaming Video], about the rise of the prison system as the new asylum.

In addition, the hegemony, or dominance, of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) began to attract attention, with critics examining both the processes by which the successive editions had been produced and the intended and unintended effects of its widespread use. The sources and the impact of the psychopharmacological revolution drew increased interest, with attention paid to both the role of the pharmaceutical industry and changes in the intellectual orientation of the psychiatric profession.

In Chapter 3, we discussed Emile Durkheim’s book Suicide, in which he systematically studied suicide rates in France. An upward trend of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic despite the suicide rate remaining stable (Yan et al. 2023).

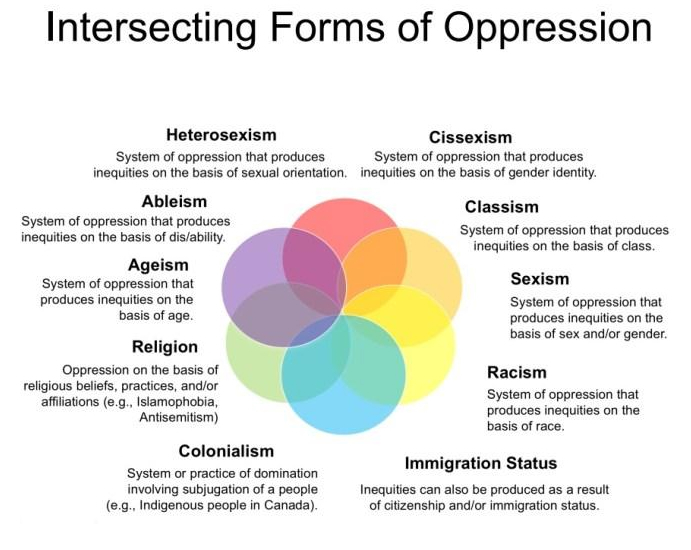

Intersectional

We introduced the concept of intersectionality in Chapter 2, as a way of identifying your own social location. Another way of understanding intersectionality is by looking at categories of oppression. This intersection is detailed in Figure 12.24.

Each of these layers of oppression connects with the other sources of oppression. Social locations such as race, ethnicity, class and socioeconomic status, sexuality, sex, and gender all impact mental health outcomes.

Patrica Hill Collins first wrote about intersectionality. However, Kimberlé Crenshaw, who popularized the concept of intersectionality, spoke recently about the urgency of intersectionality. If you would like to learn more, please watch this 18:50-minute video, The Urgency of Intersectionality [YouTube].

While watching the video, consider how intersectionality may impact mental health. How does a White woman experience a mental health crisis differently than a Black woman? One research paper examines the intersectionality of mental health, racism, sexism, and ageism. If you would like to learn more, please read Triple Jeopardy: Complexities of Racism, Sexism, and Ageism on the Experiences of Mental Health Stigma Among Young Canadian Black Women of Caribbean Descent [Journal Article].

Scholars working on the sociology of mental illness thus now confront a very different research environment than the one that prevailed a quarter century ago. Dramatic shifts in mental health policy, practice, and impact require careful sociological analysis to support social justice in mental health.

Licenses and Attributions for Mental Health: Models and Treatments

Open Content, Original

“Mental Health Theory” by Kathryn Burrows is licensed under CC BY 4.0 with the exception of “The Sociological Study of Mental Illness in America.”

Open Content, Shared Previously

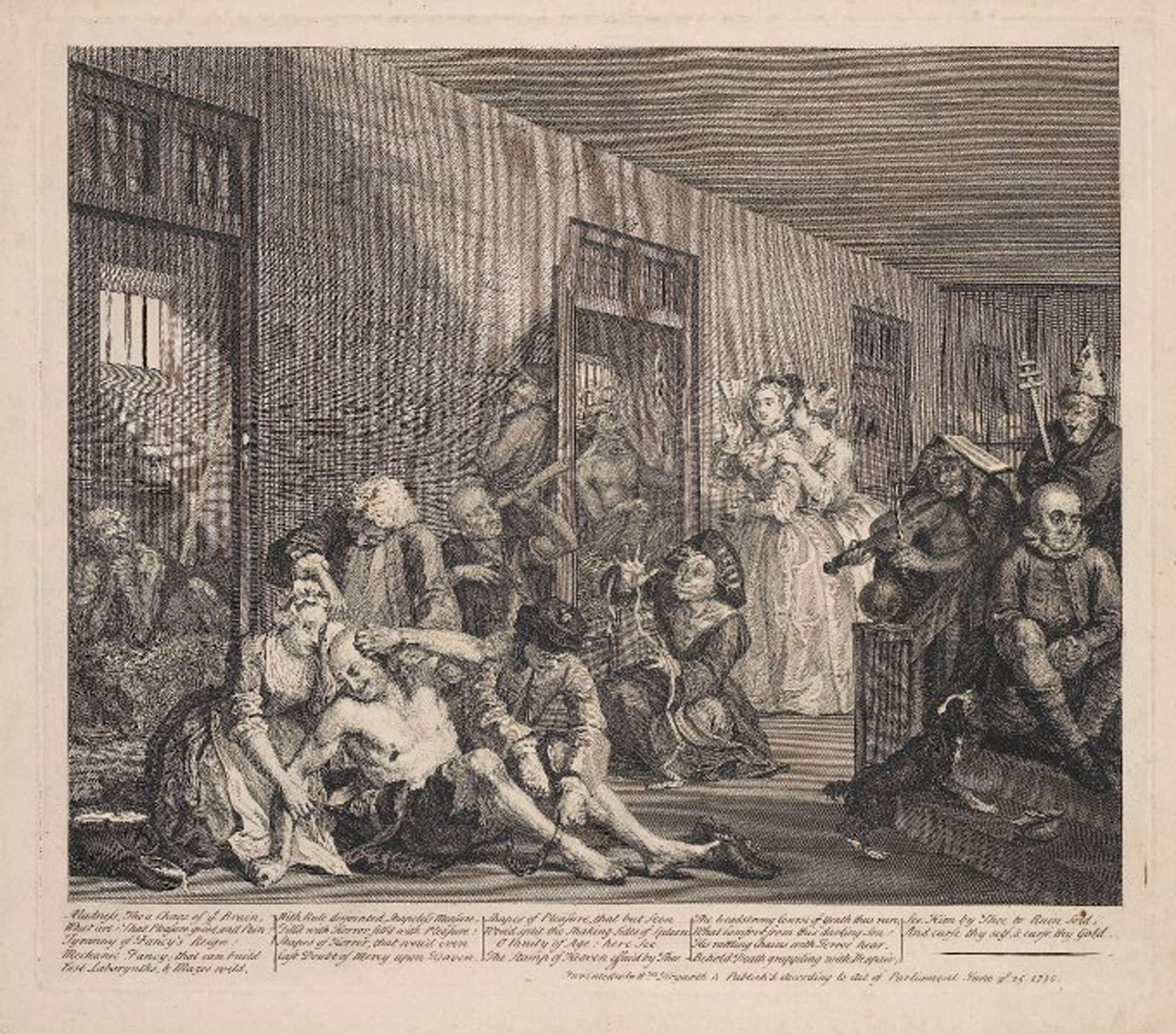

Figure 12.17. “Illustration of Bedlam” by William Hogarth is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.18. “Photo of stressed person” by Luis Villasmil is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 12.20. “Oregon Hospital For The Insane, which operated near the current Hawthorne street in Portland Oregon from 1859-1883” by an unknown photographer is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.21. “Oregon State Hospital in Salem Oregon, circa 1900” by Unknown Author is in the Public Domain. Image courtesy of the Oregon State Library Archive.

All Rights Reserved Content

“The Sociological Study of Mental Illness in America” is adapted from The Sociological Study of Mental Illness: A Historical Perspective © Andrew Scull, Mad in America: Science, Psychiatry, and Social Justice. All rights reserved. Included and adapted with permission.

Figure 12.19. “Erving Goffman” from the American Sociological Association is included under fair use.

Figure 12.22. “A unused ward entrance in the “J” building at the Oregon State Hospital in Salem in 2005” © Rob Finch, The Oregonian, and “Empty Room at the Oregon State Hospital” © Rob Finch, The Oregonian, are included under fair use.

Figure 12.23. “The New Oregon State Hospital, Interior Quads” by Jason Mortenson, Oregon Health Authority, is included under fair use.

Figure 12.24. “Intersecting Forms of Oppression” by endingviolence.org, Anthropology: Overview of the Concept of “Intersectionality” is included under fair use.

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.

a wide range of mental health conditions, disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors.

the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand individuals, groups, and institutions through data collection and analysis.

a statement that describes and explains why social phenomena are related to each other.

the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age and the systems put in place to deal with illness

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

a person (or group) response to a deeply distressing or disturbing event that overwhelms one's ability to cope, causes feelings of helplessness, diminishes self esteem and the ability to feel a full range of emotions and experiences.

an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

the behaviors and patterns utilized by an individual, such as a parent, partner, sibling, employee, employer, etc., which may change over time.

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.

an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others

shared understandings that are jointly accepted by large numbers of people in a society or social group

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

a group of individuals who are regarded by society as holding a similar position based on their age

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion.

a violation of contextual, cultural, or social norms

lacking a place to live

overlapping social identities produce unique inequities that influence the lives of people and groups.

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

an individual’s level of wealth, power, and prestige

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attractions toward another person

a biological categorization based on characteristics that distinguish between female and male based on primary sex characteristics present at birth.

a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities

discrimination or prejudice against an individual or group based on the idea that one sex or gender is better than the others

discrimination based on age