13.3 Inequality in End of Life and Death

Patricia Antoine and Kimberly Puttman

In this section we explore three ways to understand inequality in the social problem of death and dying. First, we examine the sociological concept of life course, which helps us understand the expected paths of our lives and the differences in power and privilege that occur at each stage. Then, we look more deeply at inequalities based on culture. Dominant White US culture “does” death in culturally specific ways. People from Latinx, Black, and Indigenous cultures have other ways of understanding end of life, death, and life after death. When cultures collide, we see inequality. Finally, we look at end of life. In this section, we specifically highlight the challenging social location of being rural. Ruralness itself contributes to shorter life expectancy. We’ll look at why that is.

First, let’s find out more about the relationship between power and age.

Unpacking Oppression, Living Justice

Sociologists and other social scientists study the human life course or life cycle to make sense of these questions and many more.

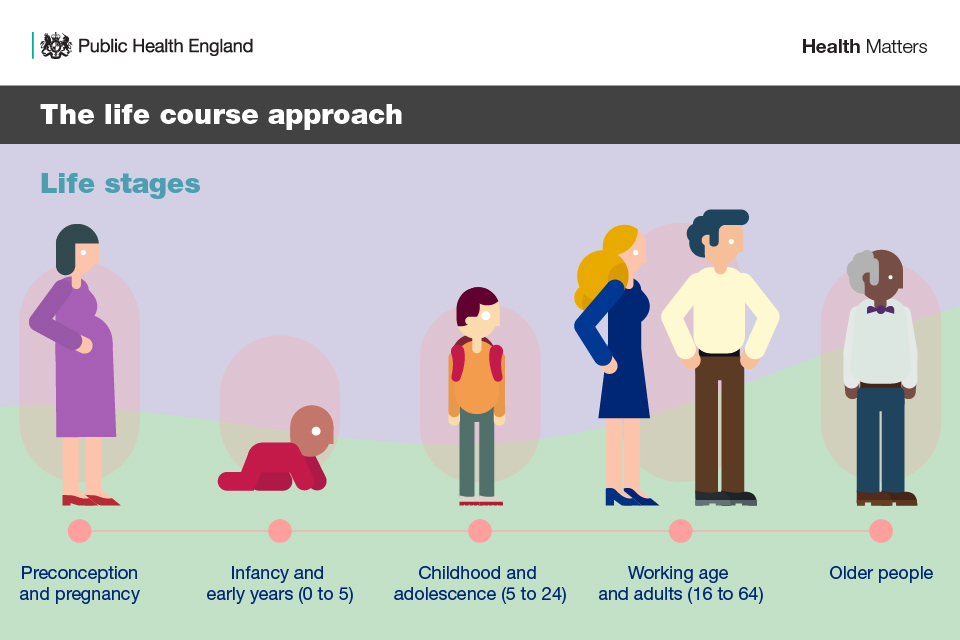

As human beings grow older, they go through different phases or stages of life (Figure 13.9). It is helpful to understand aging in the context of these phases. A life course is the period from birth to death, including a sequence of predictable life events such as physical maturation. Each phase comes with different responsibilities and expectations, which of course, vary by individual and culture.

The life course in Western societies often includes preconception and pregnancy, infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age (Figure 13.9). Children love to play and learn, looking forward to becoming teenagers. Teenagers, or adolescents, explore their independence. Adults focus on creating families, building careers, and experiencing the world as independent people.

Finally, many adults look forward to old age as a wonderful time to enjoy life without as much pressure from work and family life. In old age, grandparenthood can provide many of the joys of parenthood without all the hard work that parenthood entails. For others, aging is something to dread.They avoid it by seeking medical and cosmetic fixes. These differing views on the life course are the result of the cultural values and norms into which people are socialized. In most cultures, age is a master status influencing self-concept, as well as social roles and interactions.

You may also experience changes in power and privilege as you move through life stages. Young children, as you might expect, have little power. They depend on others to care for them. When a person turns 18 in the United States, they can vote, which is a level of power and privilege. As people move from adulthood to senior citizens, they may experience more frequent ageism, which is discrimination based on age.

Often, your power and privilege decline as you age. For example, sometimes older workers are laid off first, right before they reach retirement age, so that companies don’t have to pay full retirement benefits. Or, older people aren’t hired for jobs because hiring managers assume that they don’t understand technology, or won’t be able to keep up with the demands of the job. In an intersectional example, Black elders often can’t retire or can’t retire well because of the Black wealth gap. Because of racism in employment and housing Black families (and other families of color) cannot accrue generational wealth at the same rate as White families (National Partnership for Women and Families 2021). Therefore, they have less to fall back on when it comes to getting the care that they need during retirement, end of life, and dying.

Also, sociologists see a connection between ageism and death and dying. When people fear death and dying, they don’t want to interact with people who are aging or at the end of life. When they worry about dying, they are more likely to be ageist (Banerjee, Brassolotto, and Chivers 2021), discriminating against people as they age or enter their end of life. For example, a doctor or caregiver might assume that an older person can’t make their own end of life decisions based on their chronological age. However, age is only part of the picture. Physical health, mental health, and cognitive capacity all play a role in whether a person is capable of making decisions for themselves (Kotzé and Roos 2022).

As we look at the life course, related more specifically to death and dying, professionals use this model in two ways. The first way helps us understand what constitutes a good death. “The institute of medicine defines a good death as one that is free from avoidable death and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers in general, according to the patients’ and families’ wishes” (Gustafson 2007). Albert Albert McLeod is a Status Indian with ancestry from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation and the Metis community of Norway House in northern Manitoba. He is an activist and Two-Spirit leader. If you feel you would benefit from it, watch his description of A Good Death [Streaming Video]. If you choose to watch it, consider how your ideas about a good death are the same or different from his.

When children die, for example, grief is particularly challenging in part because their death is unanticipated and not part of the normal life course. When people who are poor die of diabetes or heart disease as young adults, this is also not a good death because these deaths could have been prevented.

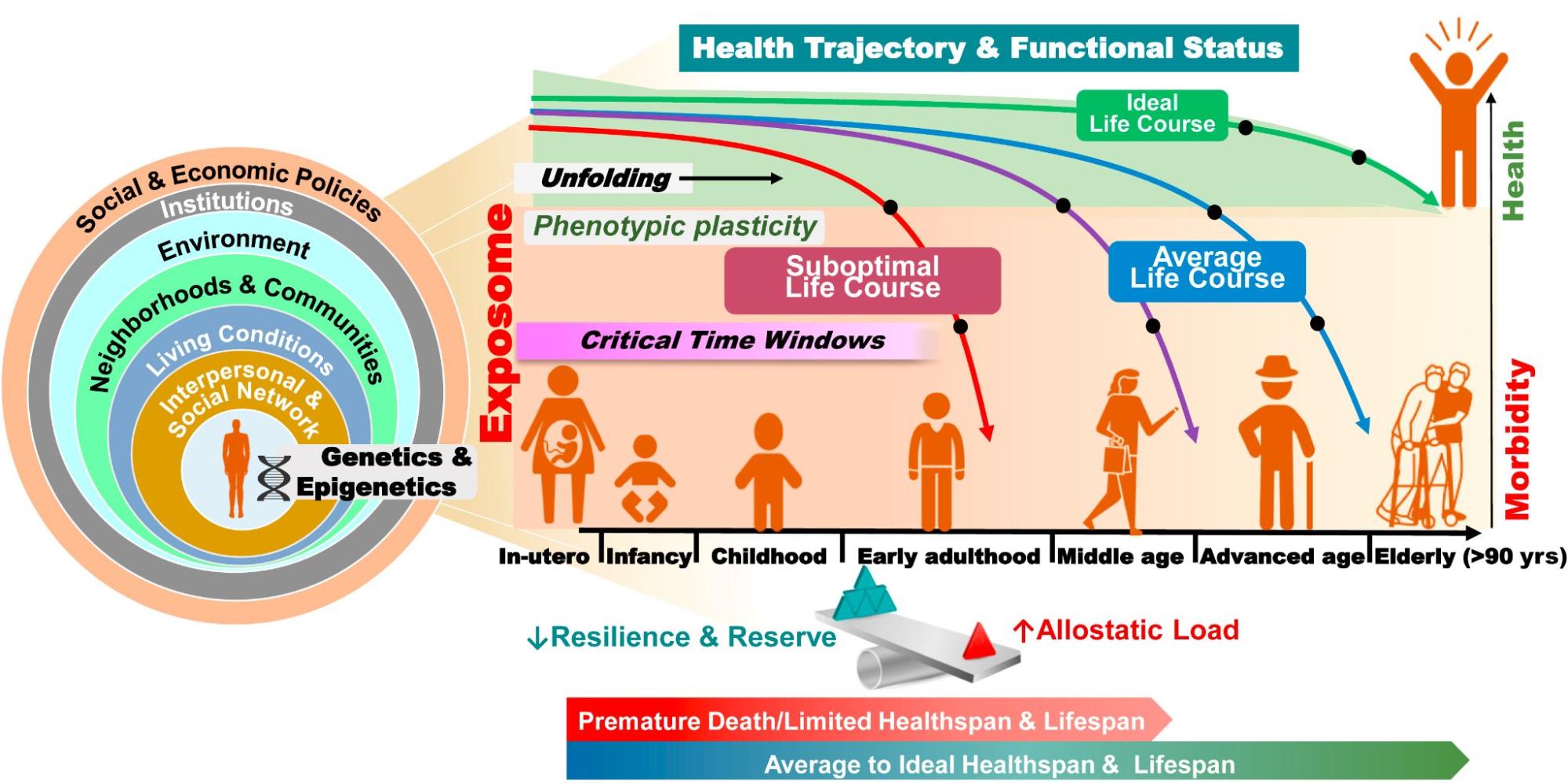

Medical professionals also integrate this idea of a good death into their models of health and illness. This infographic is intended for doctors, so it is very complicated. However, if you examine it piece by piece, you will find that we have actually covered most of these ideas in this book. The infographic helps to synthesize our knowledge.

The circles on the left side represent the social ecology model that was introduced in Chapter 3. A person’s health is impacted at the micro level of individual interactions to the macro level of the laws and policies that create or change structural inequality. People who talk about racial environmental justice, as in Chapter 8, might notice how neighborhood exposure to oil or coal burning would impact health outcomes.

The Exposome is the equivalent of Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs) or the protective factors that we discussed in Chapter 10. The chart maps resilient heath to less health during the aging process. It also shows how the likelihood of illness or death changes depending on social factors. Finally, the chart displays how health and illness may unfold over the life course, depending on social and individual factors.

The concept of life course helps sociologists understand how a “good life” and a “good death” unfold for people from a particular culture. When a life or a death does not unfold that way, sociologists can explain why. Social problems scientists can then propose action. Activists, community members, and governments can act or choose not to act to support good living and good dying for everyone.

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and live justice:

Ageism is common in our society. We privilege and promote youth and vitality. Please find an example in the media that is ageist. It can be an advertisement, meme, short video, or other media source. If you need some help thinking about what kind of attitudes and behaviors are ageist, feel free to watch Age Doesn’t Define You [Streaming Video]. Transcript

Then reflect:

- What evidence do you see that demonstrates ageism?

- What laws, policies, or practices might cause this ageism, or be sustained with this ageism?

- How does the ageism we see in our society influence our willingness and ability to talk about death and dying, or to support people who are nearing end of life?

- If you were going to create a non-ageist advertisement or media element, how would you change it?

Cultural Differences in Death and Dying

One of the ways we can think about inequality in death and dying is to consider cultural differences. Think for a minute about the last funeral you attended. For some of you, this may have been a recent experience. Others of you may never have attended a funeral. However, when we examine how people from different cultures think about and do death and dying, we notice many differences.

In dominant White culture, there is often a funeral. People come together to pay their respects to the dead person. The body of the dead person may be present in a casket, or a cremation may occur. People may also attend a viewing or wake, where they can sit with the family and the body to pray or say goodbye. There may be a burial of the body or a placement of the cremated remains in a columbarium. Finally, the process may end with a memorial service or a celebration of life, depending on the wishes and beliefs of the person or their family.

This pattern is very common. We also notice three themes related to death and dying in dominant White culture. The first is the denial of death. We don’t often talk about death, prepare for death, or talk about a person who died (Hughes 2014). Although the denial of death is not unique to US culture, the dominant US cultural norm is that young and beautiful is the right standard. We live as if we will stay young and healthy forever.

The second element of death and dying in the dominant culture is that death and dying is a big business. It costs money for the casket, for embalming the body, the cremation, the rituals, the burial plot, mausoleum, or columbarium, the flowers, the food, and all of the things associated with the funeral rites. Journalist Jessica Mitford drew attention to this problem. She wrote an article in “The Undertaker’s Racket” for the Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1963. In it, she details all of the people and all of the costs of a traditional US death. At the time of the article, she estimated that the funeral business was a 2 billion dollar industry in the US (Mitford 1963:56). As of 2023, the funeral industry makes over 20 billion dollars annually (Marsden-Ille 2023). Dying is a big business.

Finally, the dominant White culture leaves very little space for grief. Although bereavement leave exists, it is often short and unpaid. In dominant White culture, people often talk about “getting over” someone’s death as if the grief will go away at some point. It is not common to sit in prayer for several days or to restrict your activities to allow space for grief.

However, this way of dying, death, and grieving isn’t the only way. We’ll illuminate inequalities in death and dying by exploring the Day of the Dead/Dia de los Muertos in Mexican and Mexican American culture, RIP T-shirts from the Black community, and current practices in two Indigenous communities. We will use qualitative data, or stories, to do this exploration. In Chapter 4, we learned that using stories is common in both the interpretive and Indigenous scientific frameworks.

Because we are using stories, we don’t have numbers to demonstrate the inequality present between dominant and non-dominant cultures. However, doing death differently than traditional White culture requires explaining what you need and insisting that you get it—activities of resistance that take energy and focus. This additional load is an example of inequality in action.

Before we begin, let’s look at another social location: religion. As you might expect, religion has a lot to do with how we go about death and dying.

Unpacking Oppression, Believing Justice

How people deal with death and dying is often related to their religions and spiritual beliefs. Religion is a personal or institutional system of beliefs, practices, and values relating to the cosmos and supernatural. This definition has two key components. First, people experience religion as a personal set of beliefs and practices. Second, religion is a social institution, a structure of power with hierarchies, doctrines, practices, and beliefs.

The religion you belong to is often included when sociologists discuss power and privilege. In the United States, the dominant religion is Christianity. About 64% of Americans are Christian, and the number is dropping (Pew Research 2022). However, Christian privilege is embedded in our society in other ways. For example, our Pledge of Allegiance contains the words, “One nation under God.” Our national holidays include Christmas, a holiday that is only celebrated in Christianity. We most often swear oaths for public service or juries on the Bible, the holy book of Christianity. Recognized churches that closely match the Christian pattern get tax breaks. What other examples can you think of?

Other religions and spiritualities are non-dominant, even though the number of people who are not Christian is rising. With the exception of Judaism, non-Christian religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and others are growing. Additionally, people who identify as “None” or have no religious affiliation will be the majority of people in the US by 2070 (Pew Research 2022). While estimates that far in the future are somewhat unreliable, the number of “Nones” is growing.

These differences in religious power and privilege drive inequality in death and dying. Differences in religious practices around death and dying also create conflict. In some religions, for example, it is essential to cremate the body. In others, only burial will work.

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and believe justice:

Let’s explore cultural beliefs and rituals related to death and dying. For this activity, you may explore the traditions related to your own religion or culture or choose to look at something new.

You may use the information from the table in Appendix: Class Expansion Materials or the details from cultural differences that follow this activity. The open education textbook On Death and Dying has videos and pictures of several religious customs related to death. The website, Learn Religions might also help if you search related to death and dying and a particular tradition.

As you explore, please answer:

- What religion, spirituality, or culture are you examining?

- What beliefs around aging and dying does this tradition hold?

- What do people who practice this tradition think about the body?

- What funeral rites or practices does this tradition commonly do?

- How does this tradition differ from the dominant culture, if it does?

- How do differences in belief around death and dying contribute to the social problem?

Cultural Differences – Día de los Muertos/Day of the Dead

Unlike dominant White culture, Día De Los Muertos/Day of the Dead celebrates the connections between the living and the dead. If you like, you can learn more by watching Thousands pay tribute to life during Día De Los Muertos, ‘The Day of the Dead’ [Streaming Video] or Día De Los Muertos: A Brief Overview [Streaming Video]. However, one of the best ways to learn more is to read this account from Latinx Writer and activist Linda González.

Linda González Tells Her Story

Every year as November 1 approaches, I do the math to remember how long ago my father passed away on Día de los Muertos. This year, I dutifully pulled up my calculator and subtracted 1996 from 2017. Twenty-one years. And then the obvious hits me. I can always know how long it has been since he passed on to his next life by subtracting one year from my twins’ age. They are 22 and were just a year old when their abuelo died. I remember carrying Gina down the aisle behind the casket, her and Teo’s new life blooming while that same year Tot’s had faded.

I set up my altar this week, pulling out the pictures of my dearly departed and adding new ones from this year. The first step is always laying out the cross-stitched mantle with years of stains and a dark mark from when a candle burned too hot. I tape papel picado above the altar, remembering this ritual is not a dirge; it is an opening of the veil to celebrate the lives that touched me and my comunidades. It is a time to think about why I miss them and ponder how to keep them alive in the present moment.

I imagine my dad’s disappointed spirit hovering over the Dodgers as they lost in the World Series. I invoke my mom’s stovetop magic as I figure out what to do with a bag of zucchini that must be cooked tonight. I remember the mothers who grieve their sons’ vibrant spirits every day, and I take a moment to send Snapchats to my beloved cuates.

Día de los Muertos is so ingrained in my being that I am startled to see people in costume; my mind wonders for a second, “What’s that all about?” This is amazing because I was so involved in Halloween while my children were growing up—making costumes, figuring out the healthiest candy to hand out, trading my children’s candy for money so they were not overloaded with sugar (and I could store their loot for the next Halloween).

In years past, I have hosted gatherings to decorate sugar skulls, loving this tradition of blending death with creativity. I treasured giving my children and their friends the chance to be playful and imaginative with something that so many people fear. As a writer, I live in that crevice of light and shadow, writing drafts only to end their existence for another version and then another and then yet another.

I love the transparency of life and death, the calaveras that dance and meditate and watch TV. Each skeleton could be anyone of us, and one day we will know what our antepasados experienced after their last out-breath. One day we will see there is no separation between any of us, alive and dead.

Cultural Differences – Indigenous

Indigenous people in the United States experience complex issues related to death and dying. In Chapter 5, we saw how residential schools destroyed Indigenous families. In Chapter 8, we discussed how colonization harmed Indigenous people. These harms continue in the social problem of death and dying.

Maise Smith, a psychologist is Tlingit and Northern Tutchone from Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. She was born and raised in the Yukon Territory and is part of the Daklaweidi Clan. She says that people who lived in residential schools were taught not to talk, not to feel, and not to trust. When they spoke their Indigenous languages, they were punished. When they reacted to the punishment with anger, sadness, or defiance, they were punished more. These practices created a lack of trust in systems and institutions. Now, as the children of these children are dying, the families find it difficult to talk about their feelings of grief and loss. If you would like to learn more about the impact of colonization on current Indigenous families, watch this 4.15-minute video, Colonization, Trauma and Responses to Dying and Grief [Streaming Video].

At the same time, Indigenous practices related to death and dying can support families as they experience loss. Jeroline Smith is a retired nurse, consultant, and elder at Peguis First Nations in Manitoba. She describes some of these practices For example, in some Indigenous cultures, it is traditional to open windows when someone has died so that their spirit can fly free. Often women will prepare the bodies for burial or cremation. If you would like to learn more about these traditions, watch the 43-second video, Traditions when a person dies at home [Streaming Video].

Cultural Differences – Hindu

COVID-19 disrupted religious rituals related to death and dying around the world, including India. In the Hindu religious tradition, a dead body would be washed, wrapped in white cloth, and covered with flowers. Mourners visit the body to pray and pay last respects. When this is complete, the body is cremated. Cremation marks the actual death of the person. Indian sociologist Sarita Kumari writes:

… it is believed that vital breath is released by the heat of pyre and ritual of ‘kapal kriya’ (breaking of one skull). Hence, according to beliefs, death takes place during the process of cremation. Even the smoke from the pyre towards the sky is seen as a metaphor of release of soul and its integration with heaven is considered as ‘good death.’ (Kumari 2023)

In this quote, we see another way of looking at death: death that occurs with a ritual act rather than the cessation of breath. This ritual is an essential component of a good death. Cremation is a sacrifice to the Gods. After cremation, the family puts the ashes into a sacred flowing river. This practice represents the annihilation of the body through fire and flood.

One family in India struggled to do the things that their religion said were important. Indian Ph.D. candidate Jigyasa Sogarwal shares her experience when her grandfather died in a hospital from COVID-19. She says because they are migrants, they would usually need to take the body back to his village to be cremated. However, the family could not transport the body of their grandfather back to his ancestral village. Instead, they cremated the body in the local crematorium, using full personal protection. They used technology to include the family:

Extended family back at the ancestral village looked at the funeral pyre on their mobile video screens while we held our camera phones still. This was not a video chat with a best friend at the end of a busy workday. This was not a video chat of long distant lovers. This was not an office team meeting video call. My grandfather was burning to ashes, and I had to point the camera to his pyre so that his wife of forty years, his daughters, brothers, sons, grandsons and hundreds of his former students and village friends and family could see him burning (Sogarwal 2022).

In her writing, you can feel the pain that Jigyasa experienced, as she did her best to carry out the family’s traditions through the disruption of COVID-19. If you would like to read the full article feel free to look at Body of the Dead, rituals of death and disenfranchised grief in post-COVID society.

Cultural Differences – RIP T-Shirts and Social Justice

When we consider grief and social justice, one of the privileges that wealthy, White people have is time to grieve and resources to have an expensive funeral. In Black communities, on the other hand, grief is disenfranchised. This disenfranchised grief is “grief that is unacknowledged and unsupported both within their sub-culture and within the larger society” (Bordere 2016). Bordere describes this grief:

African American youth, for instance, who reside in urban areas are often disenfranchised grievers. Many African American youth cope with numerous profound death losses related to gun violence and non-death losses, including the loss of safety…[T]hese youth are often inappropriately described as desensitized. Consequently, these losses are dealt with in the absence of recognition or support for their bereavement experience in primary social institutions, including educational settings, where they are expected to continue in math and writing as if a loss has not occurred (Bordere 2016).

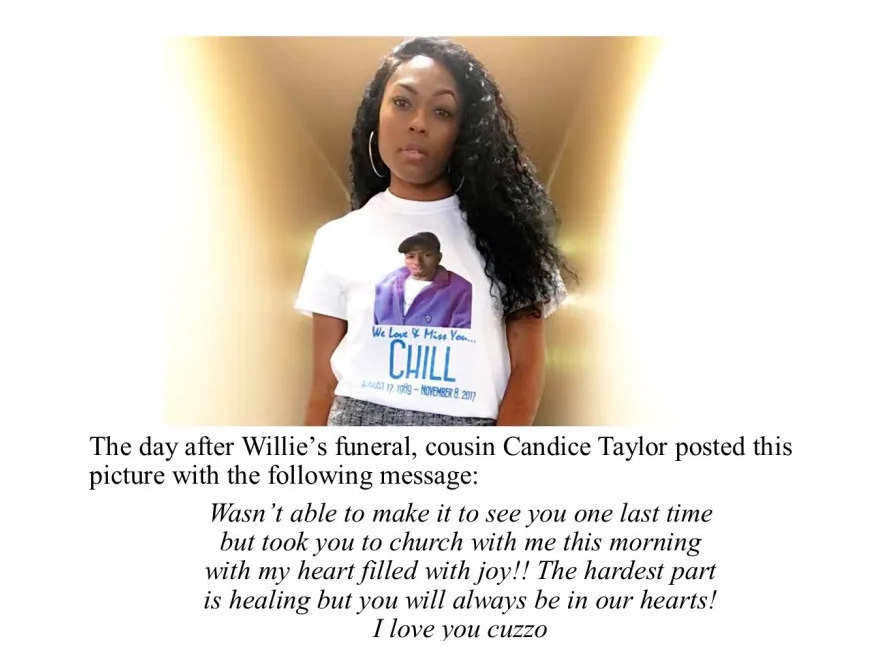

As a partial response to disenfranchised grief, RIP (Rest in Peace) T-shirts have become part of the funeral rites in Black communities. Dr. Kami Fletcher is the aunt of an African American man who was murdered. She described the RIP T-Shirts for her nephew, Willie, in this way:

As ritualized mourning wear, all of Willie’s immediate and extended kin, as well as his close friends, donned the RIP T-shirt at his wake. The T-shirts unified us in our grief while signaling to the public that we were in mourning. The T-shirts also provided solidarity, creating room for healing by memorializing his life—his place within our family and the larger community. Further still, RIP T-shirts allow room for healing by metaphorically filling the void of the loved one’s absence, serving as second skin to keep him close, and even allowing mourners to fill out the imprint he left, with our own image. (Fletcher 2020)

These shirts are also worn after the funeral itself, bringing the presence of the loved one to birthday parties or other family events.

They also become a call for justice because they remind people of the importance of the person’s life. They call out White supremacist violence by both naming and picturing the person who was murdered:

From Mike Brown and Sandra Bland to Willie Oglesby, Jr., and Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, Black bereaved family members politicize their grief in ways that highlight the white supremacy that caused the death as well as use it as a tool to fight for justice. As a walking memorial, the RIP T-shirt is a reminder of the life cut short by injustice. It is a reminder that we have not forgotten and that we won’t forget. (Fletcher 2020).

Wearing RIP T-Shirts becomes another way to “say their name”, to make their name visible, ensuring that the consequences of racial violence are obvious. If you would like to learn more about this memorial proactively, you can read Fresh to Death: African Americans and RIP T-Shirts.

Inequality at End of Life – Rural Challenges

What does it mean to be at the end of your life? Common sense would say that end of life is the period of time before you die. However, none of us know when we will die. How, then, can we understand when the end of life happens? Researchers depend on two definitions. First, end of life is defined by Medicare and Medicaid as a person who is in a six-month or less period before their death. The government uses this definition to decide who qualifies for hospice, particularly when the government is paying for the care.

A second definition focuses on the end of life as a physical process. End of life is the period preceding an individual’s natural death from a process that is unlikely to be arrested by medical care (Hui et al. 2014). The end of life is a fertile ground for social problems. End of life decisions raise issues of culture, choice, and values. End of life options also vary depending on where you live or how much money you have. Let’s look at the case of rural living.

End of Life Care Options in the Country

In this section, we introduce the social location of being rural. Social locations such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic locality affect all aspects of a person’s life. The variability in access to resources and services based on these factors has a significant impact on the dying experience. One social location that matters is geography. People in urban areas and cities tend to have access to more services. To be rural means to live in areas that are sparsely populated, have low housing density, and are far from urban centers (US Census Bureau 2017). US rural populations tend to be older, have higher mortality rates, be more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, and be disproportionately poorer than urban populations (Rural Health Information Hub 2022).

Palliative Care

Death is an unavoidable event in the life course. We are born. Eventually, we will all die. But with the advancements in modern medicine and its ability to manage disease and prolong life, dying has increasingly become an elongated process rather than a sudden specific event. The dying process is now often the end result of chronic disease and/or age-related physical decline that can be accompanied by pain and distressful symptoms.

Palliative care is often used to improve the quality of life and relieve pain and suffering during end of life care. As a treatment strategy, palliative care is specialized medical care for people living with serious illnesses and medical conditions (Definition of Palliative Care N.d. ). The focus is on anticipating, preventing, and treating physical, psychological, and emotional pain and relieving symptoms. Because rural populations are generally older and poorer than urban populations, they have more need for palliative care, but they actually have less access to palliative care (Rural Health Information Hub 2021). Data also indicates that caregivers for the medically fragile who live in rural areas often spend more time providing care and are more likely to care for multiple people than in urban or suburban areas. This is especially concerning considering the role palliative care programs can play in supporting those who provide daily caregiving and support for loved ones (Center to Advance Palliative Care 2019).

Readily available access to palliative care has advantages for the patient, those who provide daily care, and the healthcare system. Community-based palliative care programs lower healthcare costs and reduce the need for hospitalization (Weng, Shearer, and Grangaard Johnson 2022). Early diagnosis of care needs and promptly addressing medical needs before hospital care is needed provide obvious benefits for the patient. The availability and accessibility of support services for care providers is also critical to the overall well-being of the patient and the caretakers. In addition, minimizing hospital visits helps bring down overall medical costs and conserves system-wide medical resources at a time when the healthcare system is struggling to control escalating costs.

Rural areas face disproportionate barriers in providing palliative care options. Financially, the sheer volume of patients in urban areas is better able to support the resource allocation needed for hospital and community palliative care programs. Larger patient numbers can financially support the viability of healthcare teams specifically designated and trained to provide palliative care. However, rural areas lack sufficient patient numbers and the necessary medical resources to maintain palliative care programs. These areas are hindered by geographically dispersed patients, significant travel and driving time (Figure 13.18), the lack of rural hospitals and medical specialists, and the difficulty in recruiting and retaining trained healthcare providers (Weng et al. 2022).

Nursing Care and Home Health Care

The scarcity of nursing care facilities and hospice services in rural areas poses barriers to accessing end of life care assistance with medical and personal needs. Nursing care facilities (sometimes referred to as nursing homes) are residential centers designed to provide health and personal care services for those who can no longer care for themselves. These facilities provide a broad array of services dependent upon the specific focus of a facility. Levels of service can range from assisted living settings where residents may need assistance with meals, help with medication, and housekeeping to skilled nursing care facilities where the focus is more on medical care, including rehabilitative services (e.g., physical, occupational, and speech therapy), and complete support with daily activities.

These facilities can be essential end of life options, but for rural residents, they are often not available. Rural nursing care facilities face many of the same challenges as rural palliative care programs. Rising operational costs due in part to the lower number of patients, distance to resources, and difficulty in finding and retaining trained staff have resulted in a high rate of nursing facility closures across rural America. Rural residents who must often leave their community, family, and friends to access these services face the stress of relocation and isolation because of less contact with loved ones.

When end of life health care can be delivered to a patient’s home, it can be less expensive, more convenient, and just as effective as services provided in hospitals or nursing care facilities. However, there is limited access to these services in rural areas, where the service may be based out of cities 50-100 miles away and have limited openings or long waiting lists to enroll. In many instances, there are no options available for specialized medical needs, occupational or physical therapy, or mental health support.

To help fill this service gap, telemedicine (Figure 13.19) is increasingly feasible. Research indicates that the use of telemedicine can improve access to healthcare professionals for patients at home. Its visual features allow genuine relationships with healthcare providers (Steindal et al. 2020). However for rural residents, limited cellular coverage and internet access are barriers. Any cost savings to the patient and to the health care system may be far less than what is needed for investment in extending the needed technological infrastructure.

Hospice

Hospice programs provide an important option for end of life care. Hospice is specialized healthcare for those approaching end of life. Hospice focuses on quality of life and comfort of the patient, and support’s the patient’s family. The focus of hospice care is not to cure disease or medical conditions.

Instead, the goal is to support the patient and their loved ones while facilitating the highest quality of life possible for whatever time the patient has left. To qualify for hospice services, a physician or primary healthcare provider must verify that the patient is terminally ill with 6 months or less to live. A patient’s enrollment can be extended as many times as necessary to support a patient until the end of life. A patient can disenroll whenever they choose or request re-enrollment at any time.

The focus within hospice programs is on reducing pain and keeping the patient as comfortable as possible. The broad-based approach to addressing overall well-being during end of life includes attention to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs. To address these needs, a hospice team can involve doctors, nurses, and other health care providers as needed, as well as social workers, counselors, and volunteers. Depending upon patient preference, hospice programs may include access to options such as aromatherapy, touch and massage, art therapy, music therapy, and pet therapy. These complementary services can help with pain management and psychological well-being and contribute to the patient’s comfort and quality of life (Hospice Alliance N.d.).

Although hospice programs are increasingly available nationwide, less than 20% of hospices operate in rural areas. Rural hospice programs face many of the same barriers as the other end of life care options discussed above. Due to lower patient numbers, staffing shortages, high staff turnover, and long driving distances and time, they are financially vulnerable, and have limited services. This is further complicated by a common lack of available family member caregivers, which is essential to the home-based hospice option. Adult children or other caregivers often live far away, making it difficult for the dying patient to be cared for by a family member and live out their life in their home.

Although quality end of life care can take many forms, rural residents have less access to needed services during the process of death and dying. The social location of rural is a unique location of oppression.

Licenses and Attributions for The End of Life

Open Content, Original

“Inequality in End of Life and Death” by Patricia Antoine and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Life Course” and “Ageism” definitions are adapted from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Lightly edited.

“Religion” definition from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“The Process of Aging” is adapted from “Social Construction of Reality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Lightly edited.

“How I Celebrate Life on the Day of the Dead” by Linda González is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 13.8. “Photo” by Stacey Shintani on Flickr is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 13.9. “The Western model of the life course or life stages” by Public Health England © Crown copyright is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Figure 13.11. “Group of People Attending Burial” by Rhodi Lopez is licensed under the Unsplash license.

Figure 13.12. “Día de Los Muertos Celebration” by greeleygov is licensed under CC PDM 1.0.

Figure 13.14. “Photo of a personal altar” by Linda González is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 13.17. “Mt.Shasta” by Bala from Seattle, USA is licensed under CC BY-2.0; “Lincoln City, Oregon” by Lonelystudentwithtoomuchtime is licensed under CC BY- SA 4.0; “Forks, Washington” by Sea Cow is licensed under CC BY- SA 4.0.

Figure 13.18. “Photo” by NOAA is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 13.19. “Photo” by National Cancer Institute is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 13.10. “The Evolution of Health Trajectories Under the Influence of Macro- and Micro-Level Factors” by Ramachandran S. Vasan © American College of Cardiology Foundation is included under fair use.

Figure 13.13. Photo © Linda González is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 13.15. “Funeral of Arnold Billy” by Brian van der Brug, Los Angeles Times is included under fair use.

Figure 13.16. “Cousin Candice Taylor is pictured in her RIP T-Shirt” by Kami Fletcher is all rights reserved and included with permission.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

When a person’s body ceases to function

the period from birth to death, including a sequence of predictable life events such as physical maturation.

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

areas are sparsely populated, have low housing density, and are far from urban centers.

the number of years a person can expect to live, based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die.

the unequal treatment of an individual or group based on their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex)

the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns

the period preceding an individual’s natural death from a process that is unlikely to be arrested by medical care

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.

a condition where one category of people is attributed an unequal status in relation to other categories of people.

an intersectional social movement pioneered by African Americans, Indigenous peoples, Latinx, lower-income, and other historically oppressed populations fighting against environmental discrimination within their communities and across the world

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

the rules or expectations that determine and regulate appropriate behavior within a culture, group, or society

non-numerical, descriptive data that is often subjective and based on what is experienced in a natural setting

a personal or institutional system of beliefs, practices, and values relating to the cosmos and supernatural.

A large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

full and equal participation of of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs

specialized healthcare for those approaching end-of-life. Focuses on quality of life, comfort care, and medical, psychological, and social needs; treats the person and the symptoms of disease and illness rather than the disease itself; supports the patient and family

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.

the number of deaths in a given time or place

medical care focusing on relief of pain and symptoms. Meant to enhance a person's current care by focusing on quality of life and addressing what matters most to the patient.

The overrepresentation or underrepresentation of a racial or ethnic group compared with its percentage in the total population.