14.1 Chapter Learning Objectives and Overview

Bethany Grace Howe

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the social problems experienced by the people in a community before a disaster.

- Explain how disaster can exacerbate existing complex social problems in a community using qualitative and quantitative data.

- Apply sociological theories to understand the social problems inherent in disaster and disaster recovery.

- Evaluate community responses to disasters as a method for strengthening social justice.

Chapter Overview

My thanks to the survivors of the Echo Mountain Fire and the people of Otis, Oregon. Your willingness to fight to bring your neighbors home inspires both this chapter and its author.

—Bethany Grace Howe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ArwQ4YhkZUw

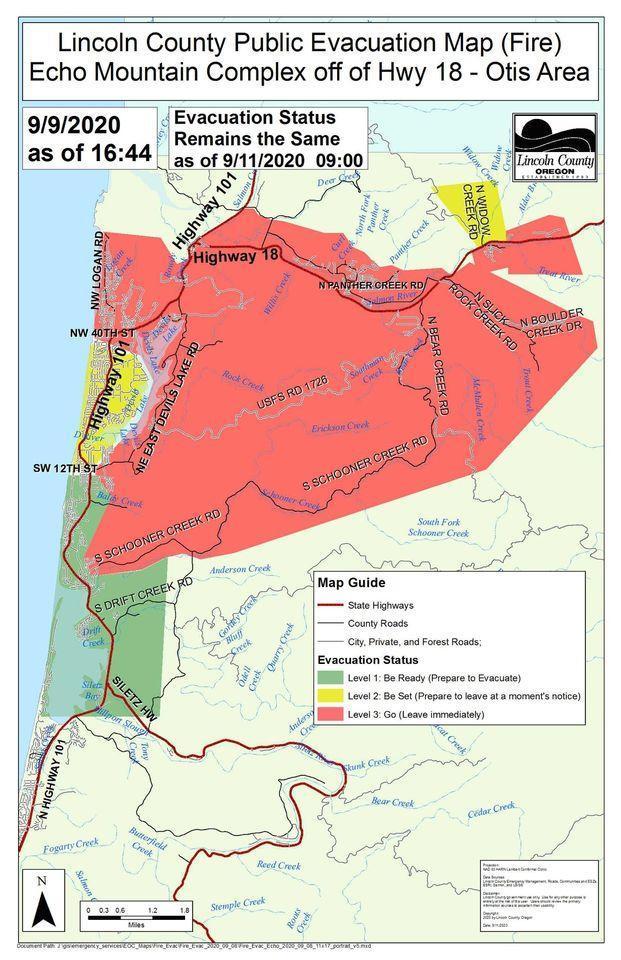

Late on the afternoon of Sept. 7, 2020, the winds were high in the Coast Range. Unexpected but powerful, the winds turned a still-unknown ignition source into rapid fire growth in the unincorporated Lincoln County town of Otis, Oregon. Please take a couple of minutes to familiarize yourself with the area, using the maps in figures 14.3a and 14.3b.

As is the case with many disasters, no one in Otis was expecting a wildfire on Labor Day weekend. Otis is located just a couple of miles inland from the coast. Wildfires were not a concern for most Otis residents in an area that gets nearly 100 inches of rain a year.

The blaze started in two places. The first fire began at the summit of Echo Mountain, approximately three miles in from the Pacific Ocean. The second started in the Kimberling Mountain area, approximately three miles east of Echo Mountain. The first fire then tore down the side of Echo Mountain, largely moving east and destroying the homes on the slopes of Echo Mountain. Simultaneously, the second fire moved west from Kimberling Mountain, where it would eventually destroy many of the homes on the banks of Panther Creek. By September 8, the blazes joined. They were officially named the Echo Mountain Complex Fire.

For area residents, this map conveyed what matters: Red was “Go now!” Yellow was “Be set to leave,” while green told them to “Be ready to leave.” September 7, 2022, started with area residents uncertain. By September 8, all of Otis and most of north Lincoln City was red.

The fire’s destruction was far from over, however. First, it moved along the north bank of the Salmon River and then along the south bank after crossing the river. Finally, it moved south and east, skipping from ridge to ridge. There, it destroyed more than a dozen more homes in the Highland Estates neighborhood and even a few on the northeast edge of Lincoln City.

We are #OtisStrong

Otis was not alone that summer. The Echo Mountain Fire was one of five major fires that destroyed thousands of homes across the state of Oregon. The statewide destruction made national news (Miller 2020). Despite being only one-quarter of one percent of the acreage burned in Oregon, however, more than six percent of the homes lost in Oregon were in Otis.

What did not make the news, however, were the long-term crises that had beset the town before the first flame erupted. Houseless people, harmful drug use, poverty, a lack of education, cultural barriers, and structural racism were just a few problems in Otis long before the fire.

To properly understand the recovery of Otis after the Echo Mountain Fire—or any community affected by the crisis—you must begin before the crisis. Before this life-changing event, both individuals and the community were experiencing multiple social problems simultaneously. Healing communities is difficult precisely because of this complexity.

For example, one long-time Otis resident could not prove to the government she deserved financial assistance without asking her abusive ex-husband to testify on her behalf. An undocumented Latino was afraid to reach out for government support for fear he and his family could be deported. A disabled senior could only sell her property because she could never afford to rebuild on it. All three of these stories—and dozens more just like them—are evidence of how structural inequalities can make community disaster recovery more difficult. More than that, they illustrate how government response to disaster can actually magnify someone’s personal crisis by ignoring the structural inequalities present in their life before the disaster.

Fortunately, the organized response to the Echo Mountain Fire was never entirely in the hands of the government. Through the efforts of volunteers and local nonprofits, the people of Otis took charge of their own recovery.

#OtisStrong was the hashtag and the name that survivors picked for themselves. Within mere days of the fire, you could buy bumper stickers and T-shirts with this logo. Later, hats sported this logo, as shown in Figure 14.4. The hashtag came to symbolize more than just a belief or a feeling. It was a commitment to action. It is the kind of action you hear about in a lot of places after a natural disaster. Families helped each other to sift through debris and move blackened trees. Community members stepped forward to lead those around them who seemed unable to take the next step.

Their response drew state and national attention for its community-centered approach to disaster recovery. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), disaster recovery is the phase of the emergency management cycle that begins with the stabilization of the incident and ends when the community has recovered from the disaster’s impacts (N.d.: 313). More importantly, the response unified a community and built a stronger Otis.

A Case Study Approach to Interrelated Social Problems

This chapter takes a unique approach to social problems in three ways. First, it was written by Dr. Bethany Grace Howe. She is a former resident of Lincoln City, Oregon. At the time of writing this chapter, she was the director of Echo Mountain Fire Relief (EMFR), an organization specifically created to support Echo Mountain Fire survivors. She is a transgender woman and LGBTQIA+ activist. She is also a journalist by training, so this chapter has a lot of stories. The “I” in this chapter refers to Dr. Howe.

And that leads us to our second point. This chapter is an extended case study. For sociologists, that means that we are diving deep into the lived experience of a community in order to more deeply understand the causes and consequences of a social problem, or in this case, a set of social problems. Case studies use qualitative data, or stories. These particular stories reflect the experiences of actual Echo Mountain Fire survivors. To protect their privacy, their names have been changed. To be clear, our goal was to support community recovery, similar to the humanitarian efforts described in Chapter 4. At the same time, we learned a lot in doing this work, and we want to share our wisdom.

Third, our goal for this chapter isn’t to introduce many new sociological concepts, although we’ll add a few about the sociology of disaster recovery. Instead, we describe the overlapping social problems that our tiny town experienced before the fire, the impact of the wildfire, and the complex processes of recovery. We are asking how a community confronts multiple social problems at once and, ideally, how the community, in the end, gets stronger. Please listen to these stories with an open mind and an open heart.

Finally, we present the specific stories so that you and your communities can become more disaster resilient to increase their ability to prevent, withstand, and recover from the harmful impacts of natural hazards on people, places, and the natural environment (Tasmania Fire Service 2023). As we pointed out in Chapter 8, climate change is increasing the amount and severity of natural disasters here and around the globe (Arcaya, Racker, and Waters 2020). Therefore, we present this case study so that you can also prepare your own families and communities. As you read, listen, and learn about this specific community, you might consider how these lessons could make your own community stronger.

Focusing Questions

In this chapter, we will explore how many of the social problems you’ve come to understand in this textbook impacted the residents of Otis, Oregon. We ask you to apply examples from the Echo Mountain Fire recovery to your exploration of these questions:

- What social problems did people experience before the natural disaster?

- How does a disaster exacerbate existing complex social problems in a community?

- How do sociologists explain disaster and disaster recovery?

- How does the weaving of community after a disaster create opportunities for strengthening social justice?

This is the story of #OtisStrong!

Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

Open Content, Original

“Chapter Overview” by Bethany Grace Howe is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

14.3a. “Lincoln County, Oregon with Fire Location” by Kimberly Puttman, based on Lincoln County Locator map by David Benbennick, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 14.3b. “Echo Mountain Fire Evacuation Map – Otis, Oregon” by Lincoln County, Oregon, Incident Information System is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.1. “Surviving Disaster” by Marc Brooks and Samanthan Kuk, Open Oregon Educational Resources is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.2. “Fire Blackened Properties, Still Smoking” © Matt Brandt Photography for Cascade Relief Team is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.4. “#OtisStrong Baseball Cap” © Amy Brown is all rights reserved and included with permission.

lacking a place to live

a person’s drug use negatively impacts their health, their livelihood, their family, their freedom, or any other aspect of their life that they deem important

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.

a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms

the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care and criminal justice

a condition where one category of people is attributed an unequal status in relation to other categories of people.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and more.

non-numerical, descriptive data that is often subjective and based on what is experienced in a natural setting

the long-term shift in global and regional temperatures, humidity and rainfall patterns, and other atmospheric characteristics