12.2 The Basics: Mental Health and Mental Illness as a Social Problem

Kathryn Burrows

In our everyday lives, we might say someone is crazy. Or we might say that we feel out of it. These terms are commonly used, but social scientists must be more precise in their language. This section explores what we really mean when we say mental health, mental illness, and mental wellness.

Once we have defined our terms, we explore why mental health and mental illness are social problems, not just individual ones.

What Do We Mean, Really?

In “Kate’s Story,” which opens this chapter, the people used their diagnosis to sort people into groups. But what does that actually mean?

Mental health is a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life (American Psychological Association 2023). It includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices.

Mental health includes subjective well-being, autonomy, and competence. It is the ability to fulfill your intellectual and emotional potential. Mental health is how you enjoy life and create a balance between activities. Cultural differences, your own evaluation of yourself, and competing professional theories all affect how one defines mental health. Mental health is important at every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood.

When sociologists study mental health, they look at trends across groups. They look at how mental health varies between all genders, different racial and ethnic groups, different age groups, and people with different life experiences, including socioeconomic status. In addition to this, though, they also explore the factors that maintain—or distract from—mental health, such as stress, resilience, and coping factors, the social roles we hold, and the strength of our social networks as a source of support.

The term mental health doesn’t necessarily imply good or bad mental health. At some times in your life, you will feel really good and have good coping skills, strong social networks, a fulfilling career, and a healthy personal and family life. At other times, things may not be going so well for you. You may have work or family conflicts, you find yourself engaging in poor coping skills, not contacting your social network for support. Both times, you are dealing with mental health. In the next section, we will explore the concept of mental illness, which, contrary to common belief, is not the opposite of mental health. Rather, it is one type of experience a person can have with their mental health.

Throughout your life, if you experience mental health problems, your thinking, mood, and behavior could be affected. Some early signs related to mental health problems are sleep difficulties, lack of energy, and thinking of harming yourself or others. Many factors contribute to mental health problems, including:

- biological factors, such as genes or brain chemistry

- life experiences, such as trauma or abuse

- family history of mental health problems

All of us will experience mental health challenges throughout our lives – times when we’re not sleeping, eating, or socializing as well as we know we could be. We may have times when we feel mildly depressed for a matter of days or just don’t feel like doing much. These experiences are common and do not mean you have a mental illness.

Mental illness, also called mental health disorders, refers to a wide range of mental health conditions and disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression and other mood disorders like bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors (Mayo Clinic Staff 2022). When substance use disorders co-occur with other mental health disorders, it is known as dual diagnosis. Having a dual diagnosis increases symptoms and decreases responsiveness to treatment. Drug use can precipitate overdoses on drugs such as methamphetamines, cocaine, and cannabis and can also worsen diagnoses such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. You already learned about harmful drug use in Chapter 11.

Unlike mental health, mental illness has a very specific definition. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and even your primary care doctor use a manual called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM is the handbook used by healthcare professionals as the authoritative guide to the diagnosis of mental disorders. DSM contains descriptions, symptoms, and other criteria for diagnosing mental disorders. The DSM lays out each condition – 297 in the most recent iteration – that professionals recognize as a mental illness (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Each mental illness listed in the DSM has a list of diagnostic criteria that a person must meet to be considered to have that particular mental illness. For example, to get an official diagnosis of major depressive disorder, a person must meet five out of eight symptoms, such as severe fatigue, feeling hopeless or worthless, or much less interest in activities they used to enjoy, for at least two weeks to be considered clinically depressed.

In addition to the definitions of mental health and mental illness that we commonly use to discuss diagnosis or lack thereof, some people are starting to use the description of mental well-being. Mental wellness is an internal resource that helps us think, feel, connect, and function; it is an active process that helps us to build resilience, grow, and flourish (McGroarty 2021). While people can support their own mental well-being with self-care activities and connecting with family and friends, the core concept is more profound. It comprises the activities and attitudes that all of us can cultivate to ensure our own resilience, whether we have a mental health diagnosis or not.

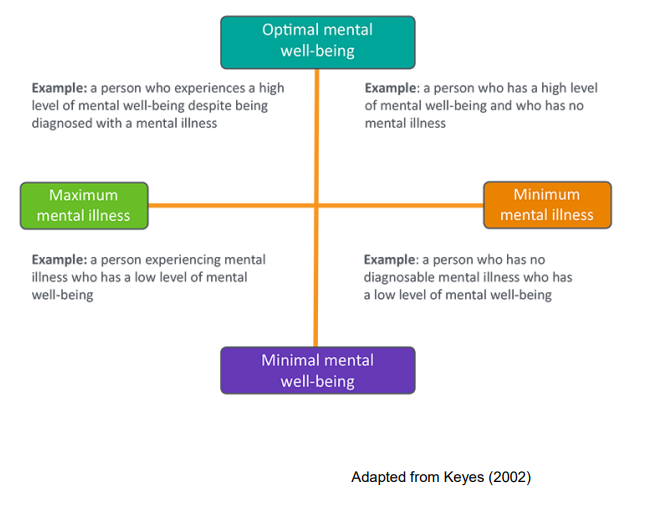

The community activists and researchers who created the phrase mental well-being use it for two reasons. First, by separating a mental health diagnosis from the quality of mental well-being, we have a model that helps us understand that mental illness can be similar to a chronic disease. You can see this model for yourself in figure 12.2. Some days, weeks, or even years, the illness is very well managed, and the person leads a productive, happy, and fulfilling life. On other days, the illness is not well managed, and the person needs more support. On the other axis, some people may experience a life event that makes them deeply sad or feel powerless. They don’t have a mental health diagnosis but may need mental health treatment or support anyway. If seeing how the model works real time will help, please watch Mental Health Continuum [Streaming Video].

Second, some people and communities stigmatize people who have mental illnesses or need mental health treatment. In those cases, using the language of mental wellbeing avoids stigma. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) hosts these sites, which you can explore if it interests you: Sharing Hope: Mental Wellness in the Black Community [Website] and Compartiendo Esperanza: Mental Wellness in the Latinx Community [Website]. Both sites have excellent videos exploring issues relating to mental wellness and resilience, mental health, and mental illness in these specific communities.

Why Is Mental Health and Mental Illness a Social Problem?

In Chapter 1, we listed the characteristics of a social problem. If you will remember:

- A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual.

- A social problem results from a conflict in values.

- A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality.

- A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences.

- A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action.

How might these apply to “Who feels OK?”

Mental health and mental illness go beyond individual experience

Mental illnesses are common in the United States. Nearly one in five U.S. adults live with a mental illness (57.8 million in 2021) (National Institute of Mental Health 2023). Mental illnesses include many different conditions that vary in degree of severity, ranging from mild to moderate to severe. Two broad categories can be used to describe these conditions: Any Mental Illness (AMI) and Serious Mental Illness (SMI). AMI encompasses all recognized mental illnesses. SMI is a smaller and more severe subset of AMI.

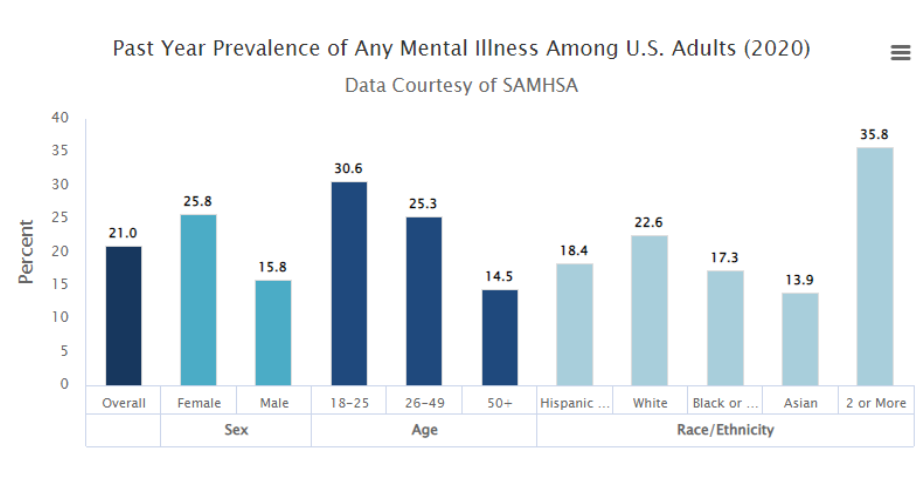

The charts below in figure 12.3 show the prevalence of AMI and SMI among adults in 2020, and the bottom chart shows the rates of mental illness in adolescents. There are some group-level differences in this data that are important to notice. The prevalence of AMI among women is much higher than that of men. There is a 10 percent gap between the two groups. Why might this be?

In this graph we see several differences between groups of people. For now, we will focus on just one of the bars on this graph: the 35.8 percent of people who experience any mental illness and report as two or more races. We’ll look at two factors that might influence the mental health of multiracial people: legal history and double-discrimination, although there are many more contributing factors.

Unpacking Oppression, Mixing Justice: The Social Construction of Mixed Race Identity

Former U.S. President Barack Obama and Vice President Kamala Harris are famous Americans who are multiracial. Obama’s mother was White from Kansas. His father was Kenyan from the Luo tribe. Although he is mixed race, he self-identifies as African American. Vice President Kamala Harris identifies as American. In most of her political work, she labels herself Black, often because mixed race wasn’t a choice. Her mother was South Asian from India, and her father was Black from Jamaica. If you would like to learn more, this article from Pew Research, “In Vice President Kamala Harris we can see how America has changed” [Website], describes several demographic trends of “mixing” occurring recently in the United States.

People from different races have always had relationships with each other. Sometimes, in the cases of slavery, these relationships were non-consensual sexual violence. The laws against miscegenation, or the mixing of two races, were only overturned at the federal level in the United States in 1967, less than 50 years ago. (Greig 2013). In fact, “the 2000 Census was the first time that citizens of the United States could select multiple racial categories for self-identification apart from Hispanic ethnicity in a census” (Whaley and Francis 2006). The lack of legal, governmental, and systems recognition of multiracial identity is an additional stress for multiracial people. If you would like to learn more, check out this blog, Laws that Banned Mixed Marriages [Website].

A second contributing factor to mental health risks for multiracial people is double-discrimination, the concept that you experience discrimination from both of your communities. This popular media article about Kamala Harris quotes Diana Sanchez, a professor who studies multiracial identity:

Sanchez says that multiracial people can face what she refers to as double discrimination, where they experience discrimination from both communities they are members of. In Harris’s case, that leads to South Asians saying she’s not South Asian enough and Black people saying she might not be Black enough. “So there’s all these different sources of discrimination that are affecting the development of your multiracial identity and your experience with it, and that can make it hard to navigate,” Sanchez said. (Chittal 2021)

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and mix justice:

If you want to learn more about the experience of mixed-race people, check out Do All Multiracial People Think the Same? [Streaming Video].

Then answer the question: Why might mixed-race people have a unique experience of social problems, including mental health and mental illness?

Social Location and Mental Illness Prevalence

Studies show that your social location—your race, class, gender, and sexuality—influences whether or not you develop a mental illness. Our social environments—the way we were socialized as children to be men or women, and the privileges and disadvantages granted by our race, class, and birth sex—all contribute to rates of mental illness. This does not mean that a particular person is more or less likely to get a mental illness but that the rate of mental illness in a particular social group is influenced by that group’s location in the social structure.

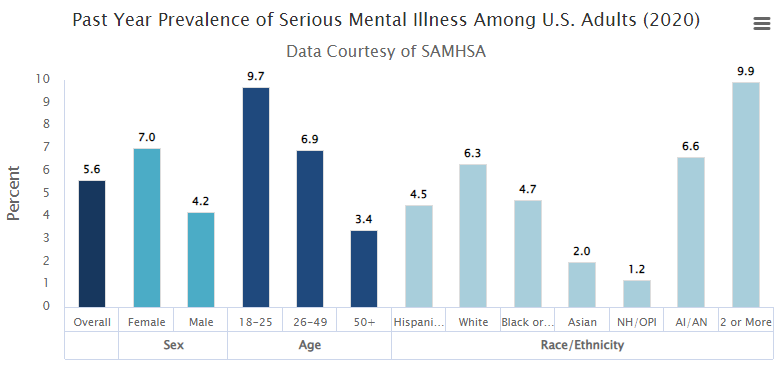

For the graph in figure 12.6, we will focus on the different prevalence of serious mental illness between women and men. Worldwide, women are more likely than men to experience mental health issues (Andermann 2010). In the past, social scientists commonly concluded that women are more emotional than men. Today, we consider other factors. In the optional article, Culture and the social construction of gender: Mapping the intersection with mental health [Website], psychiatrist Lisa Andermann calls us to look beyond individual explanations of women’s mental health and explore structural factors:

Identifying the psychosocial factors in women’s lives linked to mental distress, and even starting to take steps to correct them, may not be enough to reduce rates of mental illness or improve well-being of women around the world. More studies which take into account the interaction between biological and psychosocial factors are needed to explore the perpetuating factors in women’s mental health, and explain why these problems continue to persist over time and suggest strategies for change. And for these changes to occur, health system inadequacies related to gender must be addressed. (Andermann 2010)

In the section Unpacking Oppression, Embodying Justice of this chapter, we look at the structures of patriarchy that impact all of our lives.

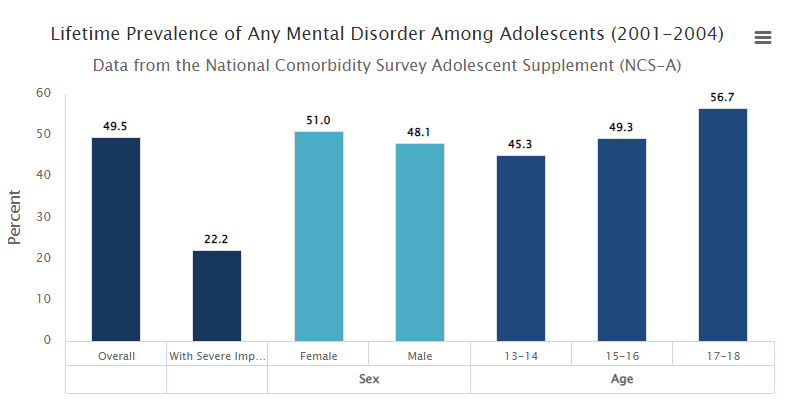

When 21 percent of all adults have a mental illness, and almost half of all teenagers have mental disorders, as demonstrated in figure 12.7, the condition goes beyond being a personal trouble and enters the realm of a public issue. The optional video, The Teen Mental Health Crisis Caused by COVID [Streaming Video], tells the story of the increase in teen suicide with the COVID-19 pandemic. Because this video recreates the experience of a parent whose child died of suicide, please skip it if you may experience harm.

Why is there such a wide difference between teenagers and adults? It’s hard to say for sure, but research offers three options:

Biology: Scientists are mapping changes in the brain in much more detailed ways. During adolescence, the brain adds new connections, particularly connections related to executive planning and regulation.

Half of adults with mental disorders experience onset of the disorder by age 14, and 75 percent of adults experience onset by age 24 (Kessler 207). Remembering that the human brain is in formation until age 25, these data suggest that experiences during adolescence shape mental health outcomes. Let’s look deeper.

Scientists are mapping brain development in new ways that reveal the importance of the neural networks that are being created in adolescence. An adolescent brain is creating new connections, particularly connections related to planning and regulation. These connections help to stabilize a person’s mental health. Further, if a person’s experience or biology does not map new connections in essential pathways, a person’s mental health may be less stable. Because adolescent brains not only respond to the same experiences as adult brains, but develop faster and more extensively, experiences in adolescence may shape the brain’s functioning more powerfully than those some experiences in adulthood. Experiences that negatively impact brain development include child and adolescent illness, hormonal shifts, exposures to toxins such as drugs and alcohol, food insecurity, trauma history, emotional and physical abuse. As we learned in Chapter 10, ACEs predict health outcomes. Impact on brain development is one of the ways in which childhood trauma impacts adult health outcomes. Specifically, trauma and stress factors negatively impact normal brain development and increase vulnerability to mental or emotional illness.

Inclusion in data: Other researchers suggest that part of the difference between the two age groups has to do with being able to contact people. Many youth are still connected with school and family, even if they are experiencing mental health issues. Most mental health surveys don’t contact people in residential living, including assisted living, group homes, prisons, or jails. Also, they do not contact people who are houseless. Because of this, mental health issues in adult and senior populations may be significantly under-reported (Kessler and Wang 2008).

More stress, less stigma: Also, researchers are exploring whether the increase in reporting of mental health issues for teens and young adults is due to experiencing more stressors or experiencing less stigma around reporting mental health concerns. This article, Why Gen Z is More Open in Talking about Their Mental Health [Website] explores this conundrum. Feel free to read it if you like.

Conflict in values

One major conflict in values we see in the social problem of mental health and mental illness is the value of community care versus the efficacy of psychiatric care. Historically, many people with mental illnesses were institutionalized. Many state hospitals provided essential care. People were isolated from their families and communities and significantly stigmatized. Also, because these facilities were often locked, outside oversight was often limited. In 1955, over half a million people were hospitalized (Talbott 2004).

Since this high, the institutionalized population has decreased by almost 60 percent (Yohanna 2013). Some of that decrease is due to a change in values. Talbott writes, “The impact of the community mental health philosophy that it is better to treat the mentally ill nearer to their families, jobs, and communities” (2004). This perspective humanizes people with this condition.

Unfortunately, government funding for community mental health services and other social supports is insufficient to meet the need. Instead of finding wrap-around support, many people who were deinstitutionalized became houseless instead (Pierson 2019).

Socially constructed but real in consequences

Scholars disagree over whether mental illness is real or a social construction. The predominant view in psychiatry, of course, is that people have actual mental and emotional functioning problems. These problems are best characterized as mental illnesses or mental disorders and should be treated by medical professionals (Kring and Sloan 2009).

But other scholars, adopting a labeling approach, say that mental illness is a social construction (Szasz 2008). In their view, all kinds of people sometimes act oddly, but only a few are labeled as mentally ill. If someone says they hear the voice of an angel, we attribute their perceptions to their religious views and consider them religious, not mentally ill. Instead, if someone insists that men from Mars have been in touch, we are more apt to think there is something mentally wrong with that person. We socially construct our concepts of mental illness, labeling some people but not others.

This intellectual debate notwithstanding, many people suffer serious mental and emotional problems, such as severe mood swings and depression, that interfere with their everyday functioning and social interaction. Other symptoms of mental illnesses include psychosis, which is the loss of contact with reality; hallucinations, which is seeing or hearing things that others cannot; and delusions, which is believing things that are not actually true. Sociologists and other researchers have investigated the social epidemiology of these problems. As usual, they find social inequality (Cockerham 2011).

Unequal outcomes

Sociologists see unequal outcomes when they examine prevalence and outcomes of mental illness. First, social class affects the incidence of mental illness. To be more specific, poor people exhibit more mental health problems than rich people.They have higher rates of severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, serious depression, and other problems (Mossakowski 2008). However, sociologists are careful not to confuse correlation with causation, a concept that we talked about in Chapter 5. Some sociologists believe that the stress of poverty can contribute to having a mental illness. Others think that having a mental illness may increase the chances that the person might be poor. Although there is evidence of both causal paths, most scholars believe that poverty contributes to mental illness more than the reverse (Warren 2009).

Second, gender is related to mental illness in complex ways. The nature of this relationship depends on the type of mental disorder. Women have higher rates of eating disorders and PTSD than men and are more likely to be seriously depressed. Still, men have higher rates of antisocial personality (a lack of empathy, or psychopathy), disorders and substance use disorders that lead them to be a threat to others (Christiansen, McCarthy, and Seeman 2022).

Although some medical researchers trace these differences to sex-linked biological differences, sociologists attribute them to differences in gender socialization that lead women to keep problems inside themselves while encouraging men to express their problems outwardly through violence (Kessler and Wang, 2008). Women are socialized to talk about their feelings more than men, who tend to be less connected to their feelings. To the extent that women have higher levels of depression and other mental health problems, the factors that account for their poorer physical health, including their higher rates of poverty, stress, and rates of everyday discrimination, are thought to also account for their poorer mental health (Read and Gorman 2010).

Mental health is a social problem, although people rarely take to the streets to protest about mental illness. In the next section, we’ll look deeper at the inequalities related to mental health and explore some of the causes of that inequality.

Licenses and Attributions for The Basics: Mental Health and Mental Illness as a Social Problem

Open Content, Original

“Mental Health and Mental Illness” by Kathryn Burrows is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Socially Constructed but Real In Consequences” and “Unequal Outcomes” are adapted from “Health and Illness in the United States” by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications: Light editing.

Figure 12.2. “The Mental Health and Well-being Continuum” from “Enhancing Public Mental Health and Wellbeing Through Creative Arts Participation” by Tony Gillam is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Figure 12.3. “Prevalence of Any Mental Illness” by the National Institute of Mental Health is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.4. “Barack Obama Official White House Photo” by Pete Souza is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.5. “Vice President Kamala Harris” by Lawrence Jackson is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.6. “Prevalence of Serious Mental Illness” by the National Institute of Mental Health is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.7. “Prevalence of Any Mental Disorders Among Adolescents” by the National Institute of Mental Health is in the Public Domain.

Figure 12.8. “Week Five – Face of depression…” by Jessica B is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life

a wide range of mental health conditions, disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors

an internal resource that helps us think, feel, connect, and function; it is an active process that helps us to build resilience, grow, and flourish

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity

a person (or group) response to a deeply distressing or disturbing event that overwhelms one's ability to cope, causes feelings of helplessness, diminishes self esteem and the ability to feel a full range of emotions and experiences

the imbibing of substances, which can happen without addiction or physical dependence but may lead to those outcomes

a person’s drug use negatively impacts their health, their livelihood, their family, their freedom, or any other aspect of their life that they deem important

the social process whereby individuals that are taken to be different in some way are rejected by the greater society in with they live based on that difference

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change, free will, or self-determination

the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision

the unequal treatment of an individual or group based on their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex)

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior

a biological categorization based on characteristics that distinguish between female and male based on primary sex characteristics present at birth

The complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups through the relationship between institutions (e.g., economy, politics, religion) and social practices (e.g., behaviors, norms, and values)

a form of mental, social, spiritual, economic and political organization/structuring of society produced by the gradual institutionalization of sexbased political relations created, maintained and reinforced by different institutions linked closely together to achieve consensus on the lesser value of women and their roles

an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus

the laws and practices that require that disabled students be included in mainstream classes - not separate rooms or schools

an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper

shared understandings that are jointly accepted by large numbers of people in a society or social group

the study of disease and health, and their causes and distribution

when a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable but does not necessarily indicate causation

a change in one variable causes a change in another variable

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life

a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one