14.2 Who Lives in Otis? Setting the Stage of Social Problems

Bethany Grace Howe

Prior to September 2020, the residents within the community of Otis might have, at best, been considered disconnected. Disconnection is the breakdown of connections among and between people (Putnam 2001). In healthy communities, most people are connected. Their connection is one element of their social capital, a concept we first examined in Chapter 11. Social capital allows people to build community because they cooperate in everyday life and trust each other. After a disaster, communities with more social capital tend to recover faster (Arcaya, Raker, and Waters 2020). However, for the people of Otis, social connections were weak at best.

The neighborhoods that long-time residents fondly remembered had been replaced by increasing gaps between middle-class residents and those who struggled to get by. Numerous homes that had once been the pride of the neighborhood had fallen into disrepair with junk and uncut weeds filling the lawn. In school, students could be heard insulting one another: “Well, at least I don’t live up Panther Crick.” At the same time, many residents were proud of their homes, but even these residents were aware that time had not been kind to Otis. The collective will to solve these problems as a community was decreasing year after year.

Who were the people who were disconnected? Let’s meet them.

Betty

In her 80s, Betty had been living on a subsistence-level income for years. Unable to even pay her property taxes, she had fallen into default years earlier. She figured someone would pay them from her small estate when she died. Betty’s life was limited by health concerns. With severe COPD, Betty no longer traveled anywhere independently other than the garden outside her front door. Her personal interactions were largely limited to the neighbors who would stop by to talk to her as she sat on her favorite bench, tended her flowers, and watched the birds.

Carol

When the fire broke out, Carol had been divorced from her husband for about one year. A survivor of spousal abuse, she had a years-long substance use disorder, most recently with methamphetamines. Since the divorce, she’d largely moved from place to place in Otis, paying cash to a variety of people so she could sleep on their couch for a few weeks at a time. Her ex-husband had agreed to let her put what few things she owned in a storage area on the edge of the property near her former home. She traded doing some yard work for even that kindness. She kept a sleeping bag there, just in case there was absolutely nowhere else to stay. Still, she rarely felt safe staying there, so she rarely did.

Fernando

Although he would eventually become the leader of fire recovery for an entire community, at the time of the fire, Fernando was one more Otis resident living in a house located where the pavement and dirt roads connected amidst the trees. He and his wife had been residents of Lincoln County for nearly 20 years after immigrating from Mexico. Their son, a local high school student, had been born in the United States. Fernando often acted as a translator and liaison to local governments and churches. Over the previous four years, they saw neighbors they had never known begin to fly Trump flags from their homes and vehicles, with stickers demonizing immigrants. In conversations, they would hear some of their neighbors say, “Send them back,” in reference to their birthplace of Mexico.

Tommy & Wendy

Just into his 70s, Tommy was in failing health. A handyman by trade, a lifetime of physical labor and accidents he could never afford to have treated properly had left him permanently disabled. He was unable to walk anything but short distances. After being struck by a forklift, a traumatic brain injury left him sometimes unable to understand basic conversations or make complex decisions. Unmarried, he rented a small, dilapidated trailer on an old friend’s property. It was not a life most people would want, but for Tommy, it was manageable, and he made it work for the most part.

Tommy’s older daughter Wendy had been in trouble as long as he could remember. A drug user since her teens, mainly of inhalants such as kerosene, paint thinner, and glue, she did manage to stay in touch with him. That’s how he’d learned a few years ago that Wendy’s harmful drug use had started following long-term sexual abuse by a family friend. Now in her early 40s, she had been hospitalized multiple times as a result of her use of inhalants. Each time the long-term damage to her liver and heart was measurably worse. Although not technically without a home, Wendy moved frequently, often living with people who enabled her harmful drug use.

Betty, Carol, Fernando, Tommy, and Wendy: five lives forever changed by the Echo Mountain Fire. The flag in figure 14.6 was a symbol of the destruction of the fire and a call to hope. For all but Fernando, the overlapping social problems of a lack of formal education, poverty, substance use disorders, and housing insecurity would impede almost every aspect of their lives in ways that even those who worked to help them would be powerless to stop.

Some of these problems had been building in their lives for decades. Others were newer, such as the political polarization of the country and the COVID-19 pandemic. Whatever the cause or how long it had been festering in Otis, however, these five, like many local residents, felt their lives and community had been under siege since long before the fire ever roared down Echo Mountain.

Unpacking Oppression, Recovering Justice

Along with stories, sociologists define populations with numbers. When we describe Otis by the numbers, we are discovering whether the folks impacted by the fire share the same characteristics as people in Lincoln County, people in Oregon, or people in the U.S.

For this activity, we’ll compare the demographics of Lincoln County and Oregon. We will consider how the two populations are different. We will also apply this information to understand what impact these differences might have on the social problems the community experiences.

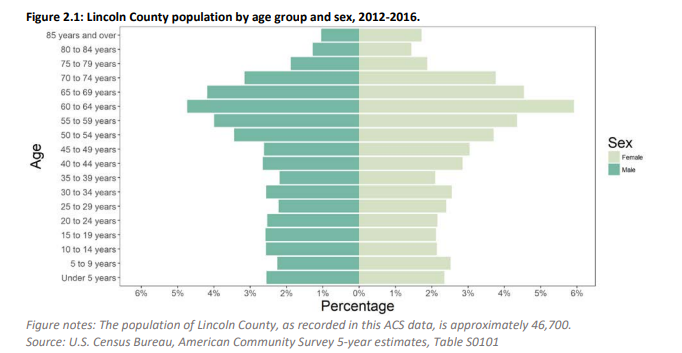

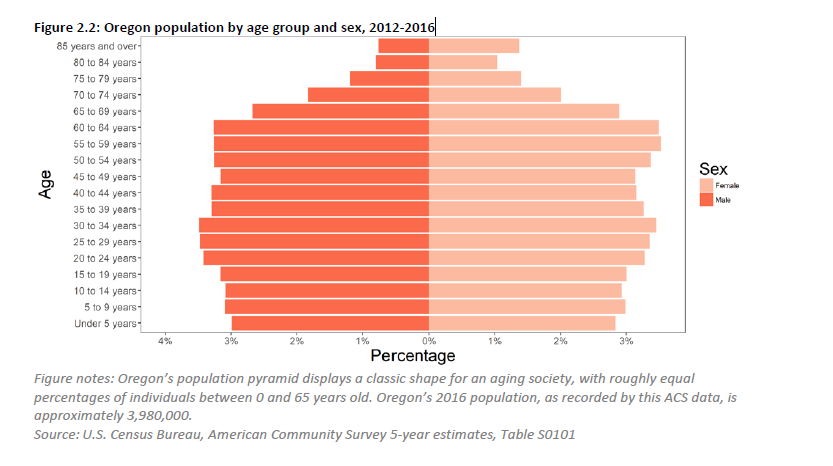

Age and Gender

When you compare the populations of Lincoln County and the State of Oregon, what do you notice? Are there the same percentages of women and men? What about young people?

Race and Ethnicity

Lincoln County, Oregon – Race and Ethnicity, as of 2022

|

Race and Hispanic Origin |

Percent |

|---|---|

|

White alone |

89% |

|

Black or African American alone |

1% |

|

American Indian and Alaska Native alone |

4.1% |

|

Asian alone |

1.6% |

|

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone |

0.2% |

|

Two or More Races |

4.1% |

|

Hispanic or Latino |

10.1% |

|

White alone, not Hispanic or Latino |

81.1% |

State of Oregon – Race and Ethnicity, as of 2022

|

Race and Hispanic Origin |

Percent |

|---|---|

|

White alone |

85.9% |

|

Black or African American alone |

2.3% |

|

American Indian and Alaska Native alone |

1.9% |

|

Asian alone |

5.1% |

|

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone |

0.5% |

|

Two or More Races |

4.3% |

|

Hispanic or Latino |

14.4% |

|

White alone, not Hispanic or Latino |

73.5% |

These numbers about race and ethnicity may not be completely accurate. On one hand, as part of our recovery efforts, we asked survivors and community organizations about the number of Latinx families who were affected by the fire. We identified approximately 25 to 30 families of Latinx heritage, like Fernando’s, who lost their homes in the fire. This matches the approximately 10 percent of the population that we see in the official count of the U.S. Census data in the chart in figure 14.8a (2022). On another hand, local community organizations estimate that the Latinx population of Lincoln County is closer to 20 percent. The U.S. Census agrees that Latinx people are underrepresented in their data, but they have yet to correct the error (Yang 2022). What might cause this discrepancy?

Social Class

As you will remember from Chapter 6, class is primarily defined as the amount of income and wealth of a group of people. Let’s look at the socio-economic status of the people of Otis. They are poorer than Lincoln City, Lincoln County, and the state of Oregon as a whole.

|

Oregon |

Lincoln County |

Lincoln City |

Otis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Living below poverty line |

11.0% |

14.4% |

15.3% |

23.7% |

|

Median household income |

$65,667 |

$50,775 |

$46,080 |

$43,594 |

As compared to the rest of the state, the number of people living in poverty in Otis is more than double that of Oregon as a whole, as shown in figure 14.9. The median household income in Otis is roughly two-thirds of that as compared to the rest of Oregon. Most people in Otis are not poor; however, Betty, Carol, Tommy & Wendy are. These numbers provide yet another piece of evidence that SES plays an enormous role in disaster recovery. The number of people living in poverty also intersects with race. In Oregon, 12 percent of the White population is poor, compared to 23 percent of the Hispanic community (Mechling 2020). These numbers reflect the disproportionate impact of race. In Lincoln County, 28 percent of Hispanic families live below the federal poverty line, a number that is also disproportionate (Lincoln County Health and Human Services 2022).

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and recover justice:

As you look at these statistics for Lincoln County and Oregon and begin to match the numbers to the stories, you get a richer understanding of this community. What about your own community? If disaster struck, who would be most at risk? One way of understanding this impact is to try the following steps:

- Go to this U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts [Website].

- Enter your state, city, or zip code in the box in the upper left-hand corner.

- Now, examine what you find. What is the racial and ethnic makeup of your community? How many people are in poverty? How many own homes or rent them? How many own a computer? You can discover a lot here.

- Now, explore the map on the National Risk Index [Website]. What risks are common in this area? How likely are they to happen? (Fun fact: The wildfire risk in Lincoln County is assessed at very low.)

- Finally, please apply the lens of social location to thinking about a disaster. How vulnerable are people in your community to the disasters that are likely to occur where you live? How long might it take them to recover?

Now that you know about your community, let’s return to Otis and see what happens to Betty, Carol, Fernando, Tommy, and Wendy.

Licenses and Attributions for Who Lives in Otis? Setting the Stage of Social Problems

Open Content, Original

“Who Lives in Otis?: Setting the Stage of Social Problems” by Bethany Grace Howe is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Unpacking Oppression, Recovering Justice” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 14.8a and b. “Composition of the population of Oregon as a whole and Lincoln County” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Figure 14.9. “Percent of Poverty line and median household income Oregon, Lincoln County and Otis” by Bethany Grace Howe is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.6. “The Flag flies over Otis, Oregon” by an unknown author is all rights reserved.

Figure 14.7 (top). “Lincoln County by Age and Sex” by Lincoln County Health and Human Services is included under fair use.

Figure 14.7 (below). “Oregon by Age and Sex” by Lincoln County Health and Human Services is included under fair use.

the breakdown of connections among and between people

the social networks or connections an individual has available to them due to group membership

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

the money a person earns from work or investments

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity

a person’s drug use negatively impacts their health, their livelihood, their family, their freedom, or any other aspect of their life that they deem important

the imbibing of substances, which can happen without addiction or physical dependence but may lead to those outcomes

a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life

a broad set of challenges, such as the inability to pay rent or utilities or the need to move frequently

an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion

the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns

the behaviors and patterns utilized by an individual, such as a parent, partner, sibling, employee, employer, etc., which may change over time

the phase of the emergency management cycle that begins with the stabilization of the incident and ends when the community has recovered from the disaster's impacts

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege