3.3 Classical Sociological Theory

Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman

Theories can be categorized as either macro or micro, based on the size of the phenomenon they seek to explain. A macro-level theory examines larger social systems and structures, such as the capitalist economy, bureaucracies, and religion. Marx and Engels critique of capitalism is a macro-level theory. A micro-level theory examines the social world in finer detail by discussing social interactions and the understandings individuals make of the social world.

A good example of micro-level theory comes from Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman, who studied one-on-one social interactions and the meanings that emerged from them. Goffman (1963) is famous for having created a theory about stigma, the social process whereby individuals who are different in some way are rejected by the greater society in which they live based on that difference. He explains that stigma is generated when a person possesses an attribute that makes them different and may cause them to be perceived as bad, dangerous, or weak.

Goffman (1963) writes that the person possessing this attribute of stigma, “is thus reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (p. 3). The possession of stigma can introduce tension into everyday social interactions (Bell 2000). Stigma plays the role of a mark that links its bearer to undesirable characteristics, which in turn causes the stigmatized person to experience rejection and isolation (Link et al. 1997). As we will discuss more in Chapter 12, having a diagnosis of mental illness often carries stigma.

Micro-level theory has a long history within sociology. One of the most common micro-level approaches is symbolic interactionist theory, a sociological approach that focuses on the study of one-on-one social interactions and the meanings that emerge from them.

Goffman’s theories have roots in social theory created in the early 20th century by George Herbert Mead, an American philosopher who described how social processes created one’s understanding of oneself or their social self. According to Mead (1934), the self is not a biological body or an inherent personal quality. Instead, the self is an image generated entirely from experiences in the social world. The social insights offered by Goffman, Mead, and other symbolic-interactionists help us understand how situations come to be defined as social problems through the meanings made in social interactions between people. As we know, situations are not automatically defined or understood as problems. We attach meanings and labels to situations that make them social problems.

Many sociology textbooks organize their material around theoretical frameworks, groups of theories that share common characteristics. The three classical frameworks are structural functionalism (often shortened to functionalism), conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism (often shortened to interactionism). These frameworks tend to correspond to theories created by prominent White male scholars of the nineteenth century. For example, Marx and Engels developed conflict theory, a sociological approach that views society as characterized by pervasive inequality based on social class, race, gender, and other factors. They argued that economic inequality created inevitable social conflict.

Because these classical theories are used so regularly within our field, we have offered a summary of each approach in figure 3.10. If you would like to learn more about these three perspectives, Major Sociological Paradigms [Streaming Video] from Crash Course Sociology can help you out.

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions | Views of social problems |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalism | Social stability is necessary for a strong society, and adequate socialization and social integration are necessary for social stability. Society’s social institutions perform important functions to help ensure social stability. Slow social change is desirable, but rapid social change threatens social order. | Social problems weaken a society’s stability but do not reflect fundamental faults in how the society is structured. Solutions to social problems should take the form of gradual social reform rather than sudden and far-reaching change. Despite their negative effects, social problems often also serve important functions for society. |

| Conflict theory | Society is characterized by pervasive inequality based on social class, race, gender, and other factors. Far-reaching social change is needed to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to create an egalitarian society. | Social problems arise from fundamental faults in the structure of a society and both reflect and reinforce inequalities based on social class, race, gender, and other dimensions. Successful solutions to social problems must involve far-reaching change in the structure of society. |

| Symbolic interactionism | People construct their roles as they interact; they do not merely learn the roles that society has set out for them. As this interaction occurs, individuals negotiate their definitions of the situations in which they find themselves and socially construct the reality of these situations. In so doing, they rely heavily on symbols such as words and gestures to reach a shared understanding of their interaction. | Social problems arise from the interaction of individuals. People who engage in socially problematic behaviors often learn these behaviors from other people. Individuals also learn their perceptions of social problems from other people. |

The people who study the social world choose the questions that they study and the theories they explore based on the social problems they experience based on their own social location, and based on the social problems occurring in their societies. Because each theorist experiences a unique social identity, they see the world in a unique way. Researchers Jacobson and Mustafa (2019) explain it this way:

The way that we as researchers view and interpret our social worlds is impacted by where, when, and how we are socially located and in what society. The position from which we see the world around us impacts our research interests, how we approach the research and participants, the questions we ask, and how we interpret the data.

In this textbook, you may notice that we describe the social location of the theorists, researchers, and activists we reference. Often, we add a link so that, if you like, you can understand more about who the sociologists or activists are. You can draw your own conclusions about how their life experience might have impacted what they studied, or how they made sense of the social world around them. Understanding the social location of scientists and activists helps us to be conscious of our own bias related to who creates knowledge, and to work to change it.

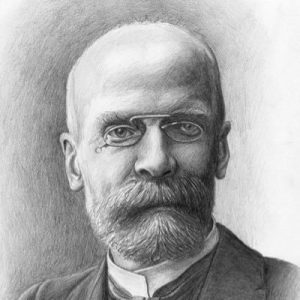

For example, French Jewish sociologist Émile Durkheim studied the social problem of suicide. He used structural functional theory, a sociological approach which maintains that social stability is necessary for a strong society, and adequate socialization and social integration are necessary for social stability. Society’s social institutions, such as the family or the economy, perform important functions to help ensure social stability. He explored the social breakdown caused by the Industrial Revolution and urbanization.

For example, the rate of suicide was increasing in France, where he lived. At that time, the Holy Roman Catholic Church described suicide as a mortal sin against God and the church. People who committed suicide were not allowed to be buried on church grounds. In contrast, Durkheim proposed several reasons that people decide to commit suicide. In his book, Le Suicide (figure 3.11) Durkheim argued that industrialization created change so fast that people couldn’t adjust quickly enough. He also said that suicides were increasing because relationships between people were breaking down. These theories helped explain the increase in suicides during industrialization. You have the option of learning more about Émile Durkheim [Website] if you wish.

English social theorist Harriet Martineau studied the social problems of poverty and slavery. Unusual for the time, she was an educated woman. Because she was both White and wealthy she was able to study and research. She traveled to the American South and interviewed people to understand more about contradictions between American ideals of freedom and liberty, and the lived reality of slavery. She also examined women’s roles, women’s rights, and family life as a field of sociological study. If you’d like, you can learn more about Harriet Martineau [Website].

German sociologist Max Weber studied the social problems of capitalism and bureaucracy. He agreed with Marx about the importance of the economic inequality driving social disruption. However, he argued economics alone was insufficient to explain revolution. He added the idea that people’s beliefs and values contributed to the choices that they made. Most specifically, he said that the value of hard work in Protestantism contributed to the spread of capitalism. If you’d like, you can learn more about Max Weber [Website].

Each of these theorists was responding to social concerns of the time in which they lived, whether they were experiencing social upheaval, war, economic depression, or economic stability. As we can see from figure 3.12, Marx, Durkheim, and Weber were responding to social forces related to the Industrial Revolution. Martineau examined changes in women’s roles related to the Industrial Revolution and the American Civil War.

Anna Julia Cooper, who we met earlier in this chapter, Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. Du Bois, explored the experiences of Black people during and after slavery. Jane Addams, who we met in Chapter 1, created services for immigrants before and after World War I. Eugene Kinkle Jones was the first person of color on the executive committee for the National Conference of Social Work. He advocated for better housing, access to healthcare, and economic opportunities for Black people (Wright et al. 2021).

All of these social theorists and activists contributed in significant ways to how we understand the reasons for social problems. They called out classism, racism, patriarchy and nativism as reasons for social inequality. However, sociological thought continues to respond to the problems of modern society. Let’s find out more!

Licenses and Attributions for Classical Sociological Theory

Open Content, Original

“Classical Sociological Theory” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.12. “Key Sociological Thinkers: Industrial Revolution to the Great Depression” by Michaela Willi Hooper and Kimberly Puttman, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Images: Harriet Martineau by Richard Evans, Karl Marx by

John Jabez Edwin Mayal, Anna Julia Cooper by C.M. Bell, Jane Addams by George de Forest Brush, Ida B. Wells Barnett by Mary Garrity, W.E.B. Du Bois by James E. Purdy, and Eugene Kinckle Jones in The Messenger are in the Public Domain.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Conflict Theory” and “Symbolic Interactions” definitions from “Sociological Perspectives on Social Problems” by Anonymous, Social Problems: Continuity and Change, University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing are licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Included under fair use.

“Stigma” definition adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary by Kenton Bell, which is licensed CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Structural Functionalism” definition from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Included under fair use.

Figure 3.10. “Theory Snapshot” from “Sociological Perspectives on Social Problems” by Anonymous, Social Problems: Continuity and Change, University of Minnesota is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 3.11. “Emile Durkheim (1858-1917)” by Tonnies, Wikimedia Commons is licensed CC BY-SA 4.0.

a statement that describes and explains why social phenomena are related to each other

a personal or institutional system of beliefs, practices, and values relating to the cosmos and supernatural

an economic system based on private ownership and the production of profit

a theory that examines larger social systems and structures, such as the capitalist economy, bureaucracies, and religion

a theory that examines the social world in finer detail by discussing social interactions and the understandings individuals make of the social world

the social process whereby individuals that are taken to be different in some way are rejected by the greater society in with they live based on that difference

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

the behaviors and patterns utilized by an individual, such as a parent, partner, sibling, employee, employer, etc., which may change over time

a wide range of mental health conditions, disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors

the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand individuals, groups, and institutions through data collection and analysis

a sociological approach that focuses on the study of one-on-one social interactions and the meanings that emerges from them

a sociological approach that views society as characterized by pervasive inequality based on social class, race, gender, and other factors

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

the sum total of who we think we are in relation to other people and social systems

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

a sociological approach which maintains that social stability is necessary for a strong society, and adequate socialization and social integration are necessary for social stability. Society’s social institutions (such as the family or the economy) perform important functions to help ensure social stability

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life

an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper

a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities

a form of mental, social, spiritual, economic and political organization/structuring of society produced by the gradual institutionalization of sexbased political relations created, maintained and reinforced by different institutions linked closely together to achieve consensus on the lesser value of women and their roles

an intense opposition to an internal minority that is seen as a threat to the nation on the grounds of its foreignness