4.2 Scientific Frameworks

Kimberly Puttman

As you saw in Chapter 3, sociology is the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand individuals, groups, and institutions through data collection and analysis. Although sages, leaders, philosophers, and other wisdom holders have asked what makes a good life throughout human history, sociology applies scientific principles to understanding human behavior.

Like anthropologists, psychologists, and other social scientists, sociologists collect and analyze data to draw conclusions about human behavior. Although these fields often overlap and complement each other, sociologists focus most on the interaction of people in groups, communities, institutions, and interrelated systems.

Sociologists study human interactions from the smallest micro unit of how parents and children bond to the widest macro lens of what causes war throughout recorded history. They explore microaggressions, those small moments of interaction that reinforce prejudice in small but powerful ways. They also study the generationally persistent systems of systemic inequality. As the COVID-19 pandemic sickens many of us and the climate crisis worsens, sociologists turn even greater attention to global and planetary systems to understand and explain our interdependence.

4.2.1 The Scientific Method

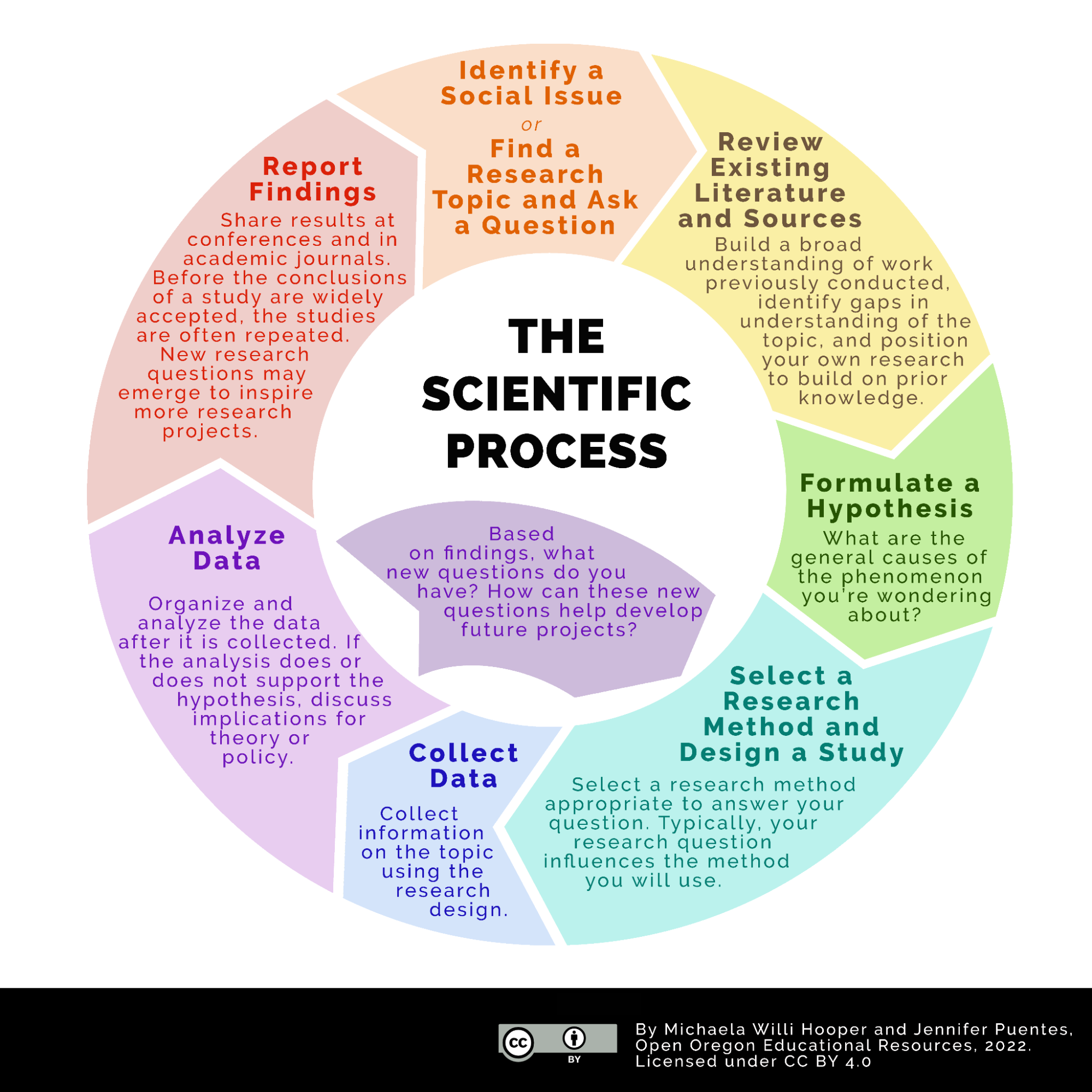

Many scientists use shared approaches to figure out how the social world works. The most common is the scientific method, an established scholarly research process that involves asking a question, researching existing sources, forming a hypothesis, designing a data collection method, gathering data, and drawing conclusions. Often this method is shown as a straight line. Scientists proceed in an orderly fashion, executing one step after the next.

This method also emphasizes objectivity, the unrealistic idea of conducting research with no interference by aspects of the researcher’s identity or personal beliefs. Science uses evidence to prove theories. At the same time, all scientists, like all people, have unconscious biases. They make assumptions about the way the world works. It is sometimes difficult to see these assumptions clearly. For example, suppose you unconsciously assume that women are weaker than men. In that case, you may label behavior emphasizing social connection as soft or passive rather than focusing on how important connection is to survival.

In some cases, scientists use pseudo-scientific methods to justify oppression. As early as 1684, French physician François Bernier classified people into different races based on where they lived in the world. Each race had a distinct temperament or set of characteristics. By the early 1800s, European and American White scientists classified people into five distinct biological races, with characteristics of more or less intelligence and diligence. In another example, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier dissected the body of Sarah Baartman, a Khoekhoen tribal African woman, in 1817:

He claimed that she had a small brain and a resemblance to a monkey. For him and many of his contemporaries, the examination of her body, and the bodies of other Africans, proved their inferiority to Europeans, showing “no exception to this cruel law which seems to have condemned to eternal inferiority the races with cramped and compressed skulls.” (Penn Museum 2023)

Both examples typify scientific racism, the use of pseudo-scientific methods to justify racial inequality. These “scientific” studies became a justification for slavery. However, even after slavery ended, scientific racism continued. In the 1800s and early 1900s, some White scientists and doctors conducted horrific experiments attempting to prove that Black people had thicker skins, felt less pain, and were less intelligent than White people (Tucker, nd, Villarosa 2021). These studies are not true.

However, we continue to see the results of these beliefs in our medical and healthcare system today. When we look at pain management, for example, Black people are 22% less likely than White patients to receive pain medication (Sabin 2020). The ways in which “science” justified racist beliefs continue to influence our health care system today. We’ll discuss this more in Chapter 10. Even though social science is based on collecting and analyzing data, it often reflects the norms and values of the scientists and the existing social hierarchies.

Because objectivity is not possible, scientists rely on collaboration to correct bias and validate results. The scientific method is a circular process rather than a straight line, as shown in Figure 4.2. The circle helps us to see that science is driven by curiosity and that learnings at each step move us to the next step in ongoing loops. This model allows for the creativity and collaboration that is essential in how we create new scientific understandings. Let’s dive deeper!

Figure 4.2. The Scientific Method is an ongoing process. Each step feeds the next step. How is this different from a linear model you may have previously learned about? Image Description

Step 1: Identify a Social Issue or Find a Research Topic and Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Why do societies have inequality” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to be of significance. “Why do my parents get into fights?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

Step 2: Review Existing Literature and Source

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly.

To study crime, for example, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police database, and prison information. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research to determine how you might use these resources to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a testable educated guess about predicted outcomes between two or more variables. In sociology, the hypothesis often predicts how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variable (IV), which is the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV), which is the effect or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable, and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe its influence on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the homeless rate. | Affordable Housing | Rate of Houselessness |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. | Math Tutoring | Math Grades |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. | Factory Lighting | Productivity |

| The greater the amount of media coverage, the higher the public awareness. | Media Coverage | Public Awareness |

Figure 4.3. Examples of dependent and independent variables. The independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way. What are some other examples?

Taking an example from Figure 4.3, a researcher might hypothesize that if the amount of affordable housing (independent variable) increases, the rate of houselessness (dependent variable) would decrease. Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. It’s not enough that two variables are related. Scientists must predict how a change in the independent variable causes a change in the dependent variable.

Step 4: Select a Research Method and Design a Study

Researchers select an appropriate research method to answer their research question in this step. Surveys, experiments, interviews, ethnography, and content analysis are just a few examples that researchers may use. You will learn more about these and other research methods later in this chapter. Typically, your research question influences the type of methods you will use.

Step 5: Collect Data

Next, the researcher collects data. Depending on the research design (step 4), the researcher will begin collecting information on their research topic. After gathering all the data, the researcher can systematically organize and analyze it.

Step 6: Analyze the Data

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, tabulate or categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss what this might mean. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, researchers consider repeating the study or think of ways to improve their procedure.

Even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, the results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study but are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, for example, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis, knowing that results may support or contradict it.

Step 7: Report Findings

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develop as the relationships between social phenomena are established in broader contexts and different circumstances. However, the scientific method isn’t the only way to conduct social science.

4.2.2 Interpretive Framework

You may have noticed that most of the early recognized sociologists in this chapter were White wealthy men. Often, they looked at economics, poverty, and industrialization as their topics. They were committed to using the scientific method. Although women like Harriet Martineau and Jane Addams examined a wide range of social problems and acted on their research, science, even social science, was considered a domain of men. Even in 2020, women are less than 30% of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) workforce in the United States (American Association of University Women 2020).

Feminist scientists challenge this exclusion and the kinds of science it creates. Feminist scientists argue that women and non-binary people belong everywhere in science. They belong in the laboratories and scientific offices. They belong in deciding what topics to study so that social problems of gendered violence or maternal health are studied also. They belong as participants in research, so that findings apply to people of all gender identities. They belong in applying the results to doing something about social problems. In other words:

Feminists have detailed the historically gendered participation in the practice of science—the marginalization or exclusion of women from the profession and how their contributions have disappeared when they have participated. Feminists have also noted how the sciences have been slow to study women’s lives, bodies, and experiences. Thus from both the perspectives of the agents—the creators of scientific knowledge—and from the perspectives of the subjects of knowledge—the topics and interests focused on—the sciences often have not served women satisfactorily (Crasnow 2020).

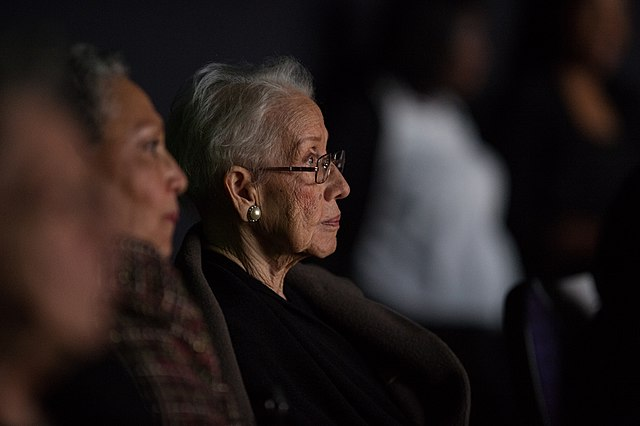

Figure 4.4. NASA “human computer” Katherine Johnson watches the premiere of Hidden Figures after a reception where she was honored along with other members of the segregated West Area Computers division of Langley Research Center.

You may have seen the movie Hidden Figures or read the book. In Figure 4.4, Katherine Johnson, an African American mathematician, physicist, and space scientist, watches the movie’s premiere. In it, women, particularly Black women, were the computers for NASA, manually calculating all the math needed to launch and orbit rockets. However, politicians and leaders did not recognize their work. Even when they were creating equations and writing reports, women’s names didn’t go on the title pages.

The practice of science often excludes women and nonbinary people from leadership in research, research topics, and as research subjects. The feminist critique of the traditional scientific method, and other critiques around the process of doing traditional science created space for other frameworks to emerge.

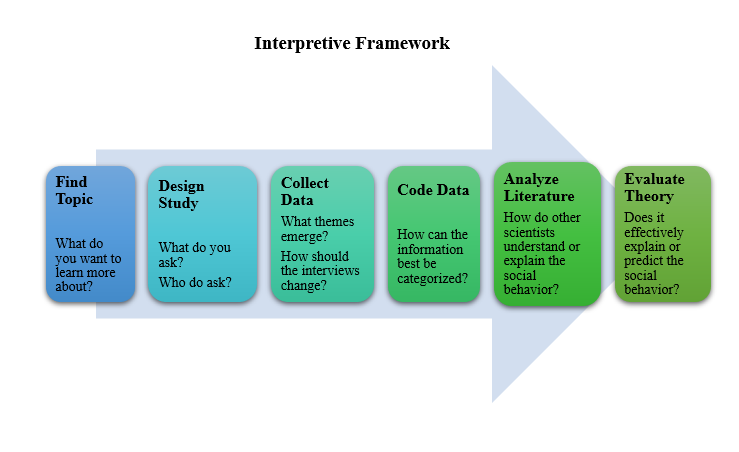

One such framework is the interpretive framework. The interpretive framework is an approach that involves detailed understanding of a particular subject through observation or listening to people’s stories, not through hypothesis testing. This framework comes from grounded theory developed by sociologists Glasser and Strauss, grounding a theory first in data and then theorizing (Chun Tie, Birks and Francis 2019).

Researchers try to understand social experiences from the point of view of the people who are experiencing them. They interview people or look at blogs, newspapers, or videos to discover what people say is happening and how people make sense of things. This in-depth understanding allows the researcher to create a new theory about human activity. These steps are similar to the scientific method but not the same, as shown in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5. Interpretive Framework: Rather than starting with a hypothesis, you start with a topic and ask people about it. As you look at the interview data, themes emerge. How is this model different from the scientific method? Image Description

In the interpretive framework, the researcher might start with a topic they are interested in. In one study, researchers were interested in improving medical care for women potentially experiencing miscarriages. They wanted to understand the experience of going to the emergency room from the perspective of pregnant women. They designed interviews that asked the pregnant women and the nursing staff about their experience. During the interviews, the women mentioned that most emergency room personnel did not include their partners in the process. The researchers added interviewing the partners as part of their study design.

Once the interviews were complete, the researchers analyzed the data and identified themes. They proposed a model called “Threads of Care” which emphasized the need to include both the pregnant person and the partner in understanding the physical processes associated with miscarriages and in providing gender-specific emotional support. Because the scientists included partner interviews, they discovered that both people involved in the pregnancy experienced uncertainty, loss, and grief, not just the pregnant person (Edwards et al 2018).

Even though both the traditional scientific method and the interpretive framework start with curiosity and questions, the people who practice science using the interpretive framework allow the data to tell its story. Using this method can lead to insightful and transformative results. You can find things you didn’t even know to expect because you are listening to what the stories say.

However, the scientific method and the interpretive framework are not the only frameworks that sociologists use to explore the social world. We also use the Indigenous framework.

4.2.3 Indigenous Frameworks

Our research has shown us that Indigenous sciences and foundational principles have the power to heal and rebalance in this world, as well as to address serious illness. Our intent is to open a pathway that would allow for this knowledge and understanding to safely and respectfully be introduced—or in some cases reintroduced—to the world through science.

—Joseph American Horse, leader of the Oglala Lakota Oyate

Like the feminist scientists discussed the previous section, Indigenous scientists provide an alternative framework to mainstream science. Each Indigenous group has a unique way of understanding their own land and a method of learning that respects that place. At the same time, many Indigenous scientists share similar frameworks. Indigenous science is the scientific framework of Indigenous cultures worldwide, a time-tested approach that sustains the community and the environment.

Although mainstream scientists and Indigenous scientists share a common goal of understanding the social world, the frameworks that they use to create that understanding are deeply different. We will examine differences in their approaches to discovery, research methods, and consequences of doing science to more deeply understand the power of the Indigenous framework. Then, we will explore how weaving Indigenous and mainstream ways of knowing can lead to transformational knowledge that supports social justice.

You may remember from chapter 3 that people use different ways of knowing to understand the social world. Indigenous scientists value many ways of knowing. Robin Wall Kimmerer, an Indigenous biologist from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, writes this:

Native scholar Greg Cajete has written that in indigenous ways of knowing, we understand a thing only when we understand it with all four aspects of our being: mind, body, emotion, and spirit. I came to understand quite sharply when I began my training as a scientist that science privileges only one, possibly two, of those ways of knowing: mind and body. As a young person wanting to know everything about plants, I did not question this. But it is a whole human being who finds the beautiful path. (Kimmerer 2013)

Although Kimmerer is referring to biology, the same difference exists in social science. Mainstream social scientists using the scientific method focus on intellectual ways of knowing. Indigenous social scientists leverage the power of knowing through mind, body, emotion and spirit. Let’s look at each of these characteristics in turn.

First, both frameworks value the mind, the intellectual understanding of what is. However, they focus on two different ways of organizing that knowledge. Indigenous frameworks focus on interdependence and interconnectedness. Mainstream science will often break things down into parts to understand what each part does. While that may help understand details, it doesn’t give the whole picture of a process or help understand the interdependence in the social and physical world.

In an Indigenous example, Lakota scientists use the image of a tipi to describe their scientific model. In this model, they focus on interrelatedness, interconnectedness, and the vitality of life. These components of the models are compared to tipi poles, which provide structure for the model itself. They write:

, …these foundational poles are being used to signify the principles of Mitakuye Oyasiŋ (interrelatedness), Škaŋ (the constant motion of life) and Paowanžila (interconnectedness), which serve as the basis for our scientific systems. (American Horse et al. 2023:7)

Rather than focusing on splitting things into component parts to understand them, Indigenous scientists focus on connection and relationship in social systems. They also connect back to the ancestors and forward to future generations to imagine how any findings from science might impact the people and the environment. This interconnectedness includes both space – the interconnectedness and interdependence of water, air, earth, and beings – and time – back to the ancestors and forward to next generations. This is very different from the Western scientific perspective, which presumes objectivity and does not assume responsibility towards the subjects it studies.

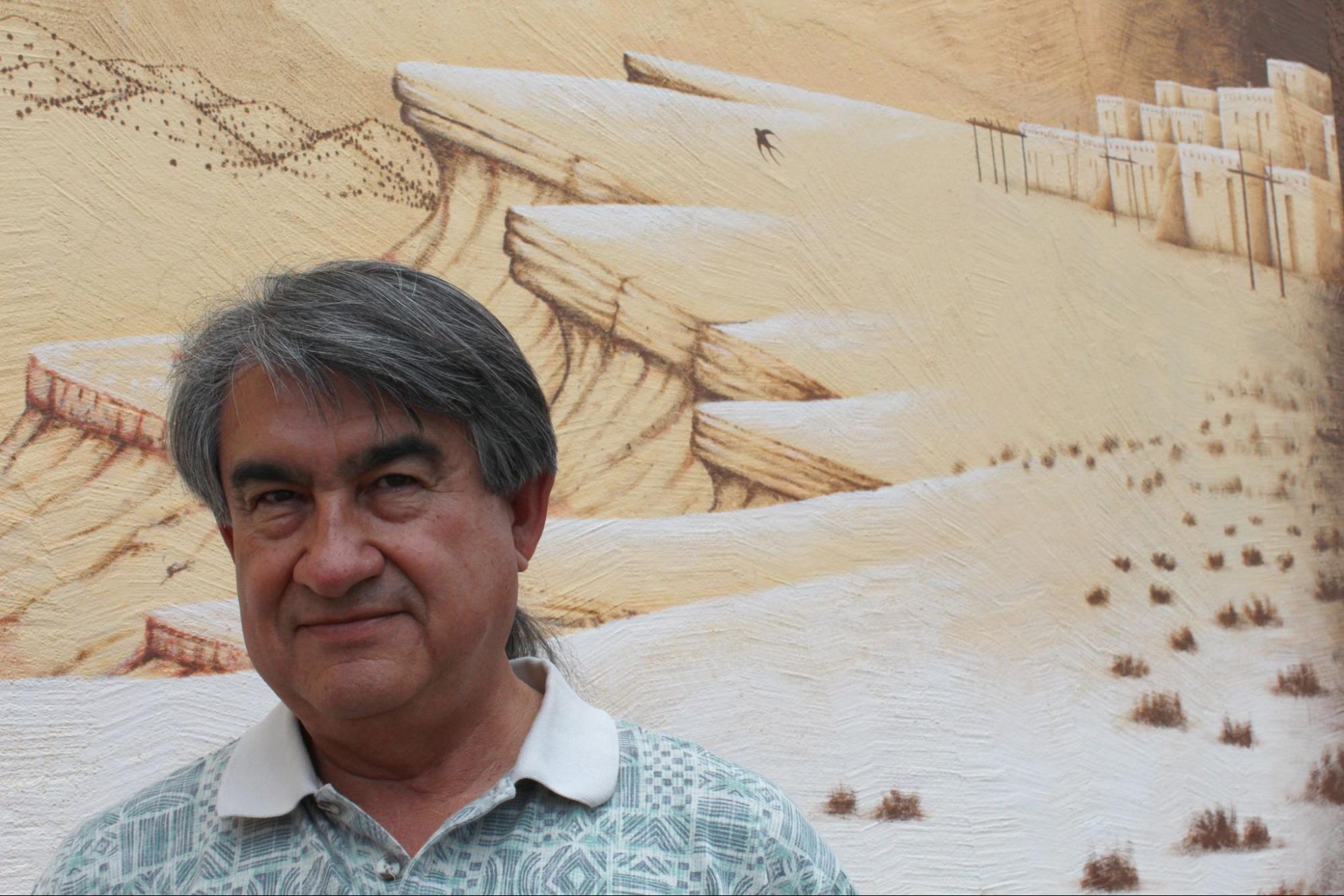

Figure 4.6. Scholar Gregory Cajete, a Tewa Indian from Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico, articulates the differences between Indigenous and Western ways of doing science.

Gregory Cajete, the social scientist that Robin Wall Kimmerer referenced earlier in the chapter, is a Tewa Indian from Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico (Figure 4.6). He describes the conflict in this way:

But the sources of knowledge of nature and the explanations of natural phenomena within a traditional Native American context are often at odds with what is learned in “school science” and proposed by Western scientific philosophy. Herein lies a very real conflict between two distinctly different worldviews: the mutualistic/holistic-oriented worldview of Native American cultures and the rationalistic/dualistic worldview of Western science that divides, analyzes, and objectifies. (Cajete 1999:146)

This conflict in approach is fundamental. At the same time, as we learned in Chapter 1, a few mainstream social scientists sometimes use models of social ecosystems and interdependence. Using interconnectedness and interdependence empowers social justice. If you’d like to learn more about the power of this perspective from Gregory Cajete, please watch A Pueblo Story of Sustainability

In addition, both frameworks consider the body, or the physical reality of social phenomenon. However, while Western science will carefully measure the parts, Indigenous scientific frameworks are grounded in a sense of place. A textbook from British Columbia is called Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science with Western Science. You can explore more if it interests you. The authors write, “In contemplating a title for this book, the phrase “Knowing Home” reflects that traditional knowledge and wisdom is contextual. The stories and testimonies of Indigenous peoples are usually related to a home place. In the words of Kimmerer:

To the settler mind, land was property, real estate, capital, or natural resources. But to our people, it was everything: identity, our connection to the ancestors, the home of non-human kinfolk, our pharmacy, our grocery store, our library, the source of everything that sustained us. Our lands were where our responsibility to the world was enacted, sacred ground. It belonged to itself; it was a gift, not a commodity, so it could never be bought or sold. (2013:17)

A sense of an interconnected place is essential in the Indigenous framework. Although mainstream social scientists will collect data about people carefully using the scientific method, their goal is to generalize their findings. Indigenous science grounds new findings within the context of a specific place in the physical world.

In the video in Figure 4.7, Kimmerer has a longer conversation about what it means to be American. Starting around minute 55:25, she discusses how the Western approach to discrete naming and classifying, apart from a place, can prevent learning. Please listen to her words and reflect on how the practices she introduces might change your own approach to science.

Figure 4.7. Biologist and storyteller Robin Wall Kimmerer reflects on the difference between naming and classifying in the Western scientific tradition and understanding relationships in the Indigenous traditions in this video: Consider This with Robin Wall Kimmerer [YouTube] (watch from 55:25 to 57:20). Transcript

Another way the frameworks differ wildly is in the integration of emotion and spirit with the mind and the body. When we examined the scientific method earlier in the chapter, we noted that the scientific method emphasizes objectivity. Mainstream scientists often argue that beliefs, values, emotions, or faith have no place in effective science. Indigenous frameworks say that emotion and spirit are valid ways of understanding the world. For example, the Lakota scientists write:

It is important to note that the Lakota do not traditionally have the concept of “religion” as is present in Western culture (Goodman 2017). Rather, Tunkašila’s [the Creator’s] energy and other dimensions are foundational to our scientific systems. Their presence is measurable, visible, and replicable. When certain conditions are created, we can enter these realms. …. They are as real and tangible as the physical earth, but exist in different energetic planes. (American Horse et al. 2023: 7, emphasis added)

Indigenous scientists incorporate both emotion and spirit into their framework arguing that the integration of mind, body, emotion and spirit are essential to both healthy living and effective science.

Differences in research methods demonstrate the impact of focusing on emotion and spirit in addition to mind and body. Like the Interpretive framework, the Indigenous framework also values story as a source of truth. Oral traditions, or stories, are one way that Indigenous people convey knowledge. Indigenous scientists value these stories as sources of wisdom and knowledge. Jacinta Koolmarie is an Adnyamathanha and Ngarrindjeri Indigenous person from Australia who is studying stories of her elders. She asserts that Indigenous stories provide valid evidence about the natural and social world. Please consider delving into that idea in her video, “The myth of Aboriginal stories being myths [YouTube].”

This perspective contradicts that of mainstream science. For example, Joel Best, who provides the model of the social problems process in Chapter 1, argues that case studies, a technical word for stories, are not useful in explaining social problems (2018). He values measurements and numbers instead. In both the Interpretive framework and the Indigenous framework, stories matter.

Figure 4.8. Horses are an active part of life for the Lakota and many other Plains nations today. How does learning more about the Indigenous history of the horse challenge the ways of Western science?

Finally, the two frameworks differ in how they think about the purpose of science. Like social problem scientists and feminist scientists among others, Indigenous scientists agree that the purpose of science is to understand more deeply so that we can take action.

Indigenous science challenges the dominant narratives of power and colonization in the Americas, for example. Colonization is the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the Indigenous people of an area. Many schoolchildren learn the mistaken idea that the Spanish conquerors brought the horse to the Americas. Indigenous oral history disagrees.

Yvette Running Horse Collins, a Lakota scientist challenges this colonialist history, examining the oral traditions of the Lakota people, finding the Creator gifted the tribe with horses long ago (Figure 4.8) She writes:

…you cannot have a Lakota separate of the horse as we were—and are—one with them. As is the case in our language, there is no past, present, or future for us with Šungwakaŋ. The Horse Nation is with us and a part of us and has been so since “time immemorial.” (American Horse et al. 2023: 21)

Her work stands in direct opposition to the more common narrative, challenging the truthfulness of colonizer accounts. This resistance is essential in the work of decolonization.

At the same time, the Indigenous framework and Western science are not binary opposites. They share a commitment to finding truth through exploring the social world. Increasingly, scientists working in both traditions are collaborating and discovering how the methods enhance one another. Using both approaches simultaneously creates powerful new knowledge that moves us toward justice.

For example, in a recent collaboration in anthropology, scientists tried to resolve the contradiction between Indigenous history and White dominant culture understandings of society and horses. Specifically, they wanted to know if horses were part of Indigenous culture before the arrival of the Spanish conquerors. The team acknowledges the colonialist viewpoint of dominant culture, writing:

Over recent decades, the story of people and horses has largely been told through the lens of colonial history. One reason for this is logistical – European settlers often wrote down their observations, creating documentary records that partially chronicle the early relationships between colonists, Indigenous cultures and horses

in the colonial West. Another reason, though, is prejudice: Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been excluded from telling their side of the story. (Taylor and Collin 2023)

Then, they use Western science to date the bones of horse skeletons, finding that the bones pre-date the colonists. They combine the quantitative data with the qualitative data gathered from Indigenous stories to tell the deeper truth. Horses were part of Indigenous culture long before the arrival of the Spanish conquerors. This evidence challenges mainstream ideas of history, and the oppression that created those ideas. If you’re interested in learning more about this powerful collaboration, you can read the full report Standing For Unči Maka (Grandmother Earth) And All Life: An Introduction To Lakota Traditional Sciences, Principles And Protocols And The Birth Of A New Era Of Scientific Collaborations.

From the Western scientific method to the Interpretive framework to Indigenous ways of doing science, we are all curious about why our social world is the way it is. We construct different frameworks to make sense of our interactions and institutions. Each framework starts from a different set of assumptions and uses different ways of gathering evidence. They each have a unique way of deepening our understanding of social problems, and moving forward with justice.

4.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Scientific Frameworks

Open Content, Original

“Scientific Frameworks” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Interpretive Frameworks” and “Indigenous Framework” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.6. “Model of the Interpretive Framework” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Dependent Variable,” “Independent Variable,” and “Hypothesis” definitions from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tanja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax, are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Interpretive Framework” definition is adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Indigenous Science” definition from Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous Science With Western Science, Book 1 by Gloria Snively and Wanosts’a7 Lorna Williams is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

“Scientific Method” is adapted from “Approaches to Sociological Research” by Jennifer Puentes and Matthew Gougherty, Sociology in Everyday Life [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Slightly summarized.

“Colonization” definition from Social Change In Societies [manuscript in press] by Aimee Samara Krouskop, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.2. “The Scientific Method as an Ongoing Process” by Michaela Willi Hooper and Jennifer Puentes, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.3. “Research Methods” is adapted from “Approaches to Sociological Research” by Jennifer Puentes and Matthew Gougherty, Sociology in Everyday Life [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Modifications: Slightly summarized.

Figure 4.4. “Hidden Figures Premiere” by Aubrey Gemignani, NASA, is in the Public Domain.

Figure 4.5. “Examples of Dependent and Independent Variables” by Jennifer Puentes and Matthew Gougherty, Sociology in Everyday Life [manuscript in press].

Figure 4.8. “Image” by MrsBrown is licensed under the Pixabay License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 4.6. “Photo of Gregory Cajete” © Gregory Cajete is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 4.7. “Consider This with Robin Wall Kimmerer” by Oregon Humanities is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 4.8. “Image” © Jacquelyn Córdova/Northern Vision Productions is included under fair use.