14.5 Indigenous Perspectives on Family, Purpose, and Meaning

Aimee Krouskop

The previous sections of this chapter reviewed Western research, theory, and models of how humans develop and pursue meaning in their lives. Those frameworks focus on developing an individual sense of purpose and meaning and applying it to one’s life, family, and community. Families and communities have a role in the way we develop our purpose and meaning, but the individual is at the center of that process.

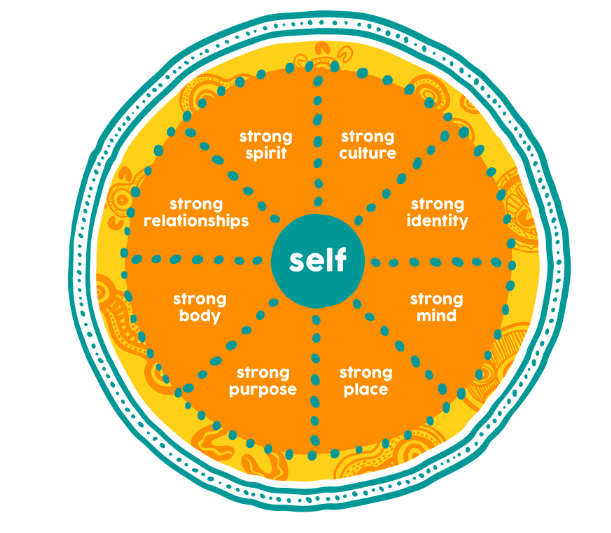

What can we glean about purpose and meaning by looking at Indigenous perspectives? While there is great diversity among Indigenous peoples, there are also some commonalities in Indigenous worldviews and ways of being. Indigenous worldviews see the whole person (physical, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual) as interconnected to the land and all plant and animal life, as well as in relationship to others (family, communities, and other nations) (figure 14.9). This is called a holistic view, and it shapes the foundation of purpose and meaning for individuals among First Nations peoples.

Let’s look at a couple of examples. The first perspective is from the Anishinaabek nation, a confederacy of nations in the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada. The second is from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia.

In the next section, the authors refer to Turtle Island, which is the name the Lenape, Iroquois, Anishinaabe, and other Woodland Nations gave to North America. The name comes from the story about Sky Woman, who fell to Earth through a hole in the sky. The earth at this time was covered with water. The animals saw her predicament and tried to help her. Muskrat swam to the bottom of the ocean to collect dirt to create land. Turtle offered to carry this dirt on his back, and the collected dirt grew into the land we call North America. The term Turtle Island is now used today in North America by many Indigenous people, Indigenous rights activists, and environmental activists.

Stages of Life

The narrative in this section is structured around the First Nations cycle of life as understood from the traditional perspective of the Anishinaabe. The discussion is broken down into the eight stages of the life cycle and the seven phases of life and has been adapted from the 2010 Best Start Resource Centre document A Child Becomes Strong: Journeying Through Each Stage of the Life Cycle.

The information provided in this section is in no way exhaustive; it is meant to act as a guide for the reader to navigate the common elements found in a diverse set of rich and complex cultural teachings that form a part of the larger First Nations world view.

Indigenous Life Cycle

First Peoples have traditionally utilized tools and knowledge from their natural environment to teach lessons within their communities. These cultural tools help First Peoples pass on essential teachings to their community members in a relevant and culturally interconnected way (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010). Many of these teachings are connected to or based upon an understanding of the four directions and the various medicine wheels discussed in this etextbook.

Across Turtle Island, the details of the medicine wheel and Four Directions teachings may differ, but often, the messages are similar (Four Directions Teachings, 2015), and we can connect them to the theme of the circle that is ever-present in the Indigenous worldview. The wheel or circle (the round shape) traditionally represents the following: Earth, sun and moon, seasons, the four directions, the four parts of the self: mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual, the interconnectedness of people, and the cycle of life (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010).

Within the framework of the circle, all elements connect with and relate to one another. For this discussion, we will specifically focus on the cycle of life, in particular, the eight stages of the cycle of life and the seven phases of life embedded in it. It is important to note that the eight stages of the life cycle are different from the seven phases of life as understood by First Nations peoples, although these stages and phases often overlap. The duration of the eight stages of life is more defined, while the seven phases of life are less uniform in length and timing and open to greater interpretation by the individual (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010).

The Eight Stages of the Life Cycle

The eight stages of the life cycle are infant, toddler, child, youth, young adult, parent, grandparent, and elder/traditional teacher. For each stage, there are teachings about healthy development, traditional milestones, and the role that a person has within their family and community (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010).

The Seven Phases of Life

The seven phases of life differ from the eight stages in that they specifically focus on the spiritual journey of a person (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010). Each of these phases emphasizes the journey of self-discovery and fulfilling one’s life purpose within an Indigenous framework. These phases often overlap. It is not uncommon for a person to enter or exit one of these phases at a completely different time than a family member or peer of the same age.

The seven phases of life are the good life, the fast life, the wandering and wondering life, the stages of truth, planting and planning, doing, and the elder and giving back life, as shown in the interactive activity below (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010).

Meaning, Purpose, and Community

Take a few minutes to click on the individual stages and phases in the interactive life cycle wheel (figure 14.10). There, you can see descriptions of the roles, responsibilities, and traditions associated with them. For example (Best Start Resource Centre, 2010; Four Directions Teachings, 2015):

The Fast Life phase spans from ages 7 to 14. During this period a child practicing traditional ways may work toward preparing for a rite of passage at the time of puberty.

These ceremonies may take many forms for both men and women. Fasting is a common component of these rites. Men will care for the boys and women will care for the girls during these celebrations of entry into adulthood. These ceremonies help youth build confidence and foster a strong sense of identity and self-esteem.

During this time youth also learn about their roles and responsibilities as men and women in their communities. After their rite of passage, they are introduced back to their communities and families as young men and young women.

Each set of roles, responsibilities, and traditions refers to ways that individuals are asked to live and grow as integrally part of their community. As they practice traditional ways such as preparing for a rite of passage ceremony with fasting or being cared for by the people in their community, they are living their purpose in meaningful ways.

Strong Purpose

Another way to understand purpose and meaning from a First Nations perspective comes from Australia. Members of Headspace, a mental health consortium, have provided some resources that express how purpose is acknowledged among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

In Focus: What Is Strong Purpose

Having a strong purpose gives you the direction, drive, and motivation to achieve what you want from your life. This might include your short- and long-term goals or creating your lived story in a way that people will remember good ways for years to come. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples might refer to this as following your dreams.

A strong purpose will help you feel like there’s meaning in your life and in the challenges you may face. Your purpose may change from time to time, and that is OK. When it does, think of what you have learnt on your journey so far and how you may be able to use this on your new path. We are collective peoples, and we naturally feel good when we feel like we are adding positively to the lives of others. Think about how your purpose and goals might bring value to your family, your community, your spirit, your identity, your country, or Mother Earth.

Chasing a Strong Purpose

You choose what your purpose is. You might have a sense of purpose that has been passed to you through your ancestral kinship connection and totem relationships or spiritual or religious influences and that’s great. But if you aren’t aware of any of these that is OK too. You can determine your own purpose from scratch.

How to Set a Strong Purpose

You are going to have to figure out how you want to fulfill your strong purpose. It can be a strong purpose with culture, school, work, or relationships.

Setting goals is a great way to start building a sense of purpose. By setting, striving for and achieving goals, you are dreaming your future each and every day. This will help keep your spirit and mind strong and help your overall well-being. How deadly is that!

What Can Impact Your Strong Purpose

Achieving your purpose requires commitment, energy, and attention. Think of it like a car—it only gets to a destination when it’s driven there. Achieving your purpose and achieving your goals is similar—you need to drive it. For example, sitting on the couch all day, taking drugs, running amuck, and spending too much time on social media will all make achieving your strong purpose more difficult. You may still get there, but the journey will be more difficult than it had to be.

Whenever something doesn’t work the way you thought it would, take a moment to reflect on it and learn. Then keep on pushing forward with that new knowledge—there’s no need to fear failure with that mindset.

This resource has been developed in partnership with the Headspace Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth Reference Group (Womenjeka Reference Group), Marumali Consultations, the Headspace National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group, and Headspace National (Gee et al., 2014).

Consider the well-being wheel in figure 14.10. “Strong purpose” is presented as a spoke along with several other key factors related to well-being, such as “strong identity,” “strong culture,” “strong relationships,” and “strong mind.” For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who hold this perspective, purpose is part of a whole set of experiences important to a strong sense of self and quality of life.

Licenses and Attributions for Indigenous Perspectives on Family, Purpose, and Meaning

Open Content, Original

“Indigenous Perspectives on Family, Purpose, and Meaning” by Aimee Samara Krouskop, with exceptions noted below. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Meaning, Purpose, and Community” by Aimee Samara Krouskop. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 14.9. Sky Woman by Ernest Smith (1936) on Wikipedia. License: Public Domain.

The second paragraph of the section “Indigenous Perspectives on Family, Purpose, and Meaning” is adapted from “Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being” in Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors by Ian Cull, Robert L. A. Hancock, Stephanie McKeown, Michelle Pidgeon, and Adrienne Vedan. License: CC BY-NC 4.0.

“Stages of Life” is adapted from “Stages of Life” in Our Stories by Centennial College. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Permission granted by Centennial College to make minor edits and add the third paragraph regarding Turtle Island. Third paragraph is adapted from the Introduction of Pulling Together: Foundations Guide by Kory Wilson and Colleen Hodgson (MNBC). License: CC BY-NC 4.0.e.

“In Focus: What Is Strong Purpose?” from “Strong Purpose” © Headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation Ltd. License: Headspace Terms and Conditions.

Figure 14.10. “Well-Being Wheel” from “Strong Purpose” © Headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation Ltd. License: Headspace Terms and Conditions. The well-being wheel is a derivative from the original work.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.9 Bear Father, Bear Sun by Norval Morrisseau. Used with permission from the Estate of Norval Morrisseau.

a systematic investigation into a particular topic, examining materials, sources, and/or behaviors.

a structural framework, explanation, or tool that has been tested and evaluated over time.

can include the emotional significance of an action or way of being; the intention or reason for doing something; something that we create and feel; closely linked to motivation.

can include the aim, goal, or intention of an action; a long-term guiding principle; the impact our life has on the world.

the developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult.

a ritual or celebration that marks the passage when a person leaves one status, role, set of conditions, or group to enter another.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

the social structure that ties people together (whether by blood, marriage, legal processes, or other agreements) and includes family relationships.

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.