12.3 Cultural Exposure Can Be Unintentional

Elizabeth B. Pearce and Christopher Byers

Families have unequal access to viewing and experiencing visual culture. Geographical location, socioeconomic status, and social characteristics all influence access to art. In particular, families in rural areas, with lower socioeconomic status, and in minoritized groups have less opportunity to accrue wealth in the United States and have fewer opportunities. In addition, they are less likely to have influence in terms of what is considered worthy to appear in curated exhibits behind museum doors.

Curated Art

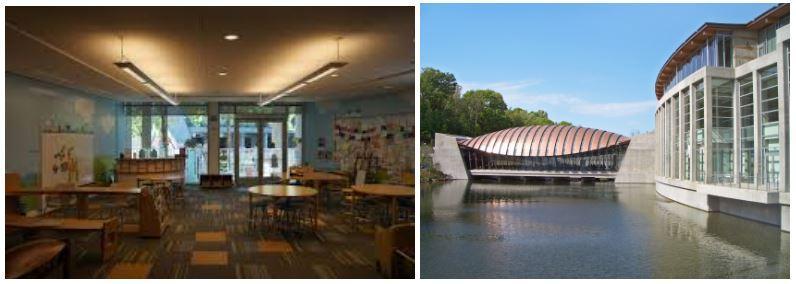

One way to measure equity in art is to examine the ability to view curated art. Access to art in childhood is especially important because activating the developing child and adolescent brain impacts eventual life outcomes. In 2011, a unique opportunity presented itself to study how child access to art affected adult outcomes. Alice Walton, a Walmart heir, founded the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, a 50,000-square-foot space with an $800 million endowment, in Bentonville, Arkansas (figure 12.6). Most children in this area had little or no exposure to art or other cultural experiences.

Class visits were provided for free via the gift of a donor. Demand was high, and not all groups who desired the visits could be accommodated. Scholars from the University of Arkansas set up a lottery system to determine which school groups would visit the museum. During the following months, all students (those who visited and those who did not) were offered free tickets to visit the museum with their families, and they were also administered a multidimensional survey. Nearly 11,000 students and 500 teachers participated in this study (Green et al., 2013).

Students who visited the museum with their classmates demonstrated stronger critical thinking skills, displayed higher levels of social tolerance, exhibited greater historical empathy, and developed a taste for art museums and cultural institutions (Kisida et al., 2013). In addition, students who had visited the museum with their class groups were 18% more likely to use the coupon to visit the museum with their families! Importantly, this effect was stronger for minority students, rural students, and low-income students than it was for White, middle-class, suburban students. While there are additional questions to be answered, this study demonstrates the importance of exposure and access to art and cultural experiences for all children. The study indicates that arts education inclusion in school curricula will help students develop critical thinking, an understanding of diverse ideas and experiences, and empathy with those who are different from themselves. Read the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art here, if you are interested in exploring this museum more.

Protest Art

Visual art as protest art is used both to promote and to express dissatisfaction with ideologies, policies, and social movements. Creative expression is used to express individual and group views, thoughts, and emotions. Because making art isn’t always an expensive venture, many can participate in it. Displays of art are not limited to inside the doors of a museum with admission fees. Anyone can access it while out and about in their daily lives; it is everywhere.

This brings us to the notion of power. When people express their thoughts and feelings via paper, canvas, media, or other outlets, it can have a powerful effect on an audience. Art that is expressed publicly is more equitably available to people in minoritized groups and with fewer socioeconomic resources.

Figure 12.7 is a visual reminder of the number of Black men and women who have been killed by police when in helpless circumstances. The protest is not only about George Floyd’s murder but also about the overall dominant culture of the police force in the United States.

Privileged groups who have a higher distribution of resources, such as wealth, may present their views via protest but also have the means to use art to catch people’s attention and promote their agendas via advertising, media, and political campaigns.

Art has a special place among activists and social movements because it can be used as a message to pay attention to a particular issue or injustice (figure 12.8). It exists in part to freely express oneself, gain attention, plant a seed, or inspire passion to actively do something about the issue.

Both protest and artistic expression are fundamental rights protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. The melding of the two creates messages that can influence and empower individuals and families. Activist artistic expression that argues for the needs of the underserved occurs around the world and does not fit into any one box.

Public Art

Much of this chapter discusses art that has some kind of paywall: museums with entrance fees or films and other media that require a ticket or subscription price. In this section, we will pay attention to art that may be considered “public” in one form or another. Public art can be created in any type of material with the form, function, and meaning intended for the general public, often through a public process. While it is also often described as representing universal concepts rather than those that are partisan, political, commercial, or personal, these authors challenge that notion from two perspectives. The first is that the funding for and decision-making about public art is still often controlled by dominant or political groups. While efforts have been made to equalize art-making decisions, the tension between money and ideals is real. Secondly, it can be said that all art is personal. What is more personal than an artist’s vision and creation? Some public art is commissioned by a public group, and this can come with restrictions or guidance for the artists. For now, we will stick with the definition that public art is art that is easily accessed by any member of society.

By its nature, public art may be viewed by anyone who can get themselves to the location it is presented. While it is more equitably accessible than art housed in museums, galleries, and media conglomerates, it is important to note that transportation, location, and resources (both time and money) prevent many families from accessing public art.

Creating and maintaining public art presents unique challenges to equity. Some citizens may hold art that is viewed or funded by the public to a different standard—one that emphasizes societal norms. Others may argue that some subjects are inappropriate to display publicly, in particular if children or young adults could view the display.

In Focus: Linn-Benton Community College and “Drawing the Line”

The tensions that can exist around public art displays were demonstrated during the 2017 exhibit “Drawing the Line” in the hallways of North Santiam Hall at Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC). Curated by LBCC art faculty and students, the fiber art of Andrew Douglas Campbell lined the halls through which the LBCC community traversed to class, the lunch commons, and offices (figures 12.9 and 12.10). Generally, Campbell explores themes of difference, connection, and identity in his work. He is an artist who merges the mediums of photography and fiber to focus on the response and interaction of social and narrative tensions. To read more from Campbell, view his website here.

The public art display at LBCC explored multiple subjects, but attention rapidly became focused on one series that examined the relationship of the porn industry and its marketing strategies to the queer community, titled …And Then What Could Happen Bent to What Will Happen… and shown in figure 12.11.

Campbell describes his process: “[I was] thinking about the porn industry as a market that I personally had not yet held with the same skeptical eye as I do a lot of other economies, and so I started to look at that and part of it is true, they have tapped into a certain desire of mine. Part of it is I’m very skeptical of it,” said Campbell. “It made sense to me that I should render their material sort of inconsequential; it’s so fragile it can be blown away. It’s important but unimportant at the same time, it’s present and not present, it’s solid and transparent. That’s where I came up with these very loose airy images that are barely there but still very impactful” (Guy, 2017).

The focus became negative; a local company that pays their employees’ tuition at LBCC and a member of the board of directors of the college were most outspoken in their belief that this work should not be displayed in a setting that was publicly accessible. There were discussions about this display at every level of the college: in offices, classrooms, and boardrooms. Ultimately, there were some alterations and adaptations to the exhibit, and it remained in place.

When considering the diverse structure and viewpoints of families in the United States, it is important to think about whether all families have access to viewing art that speaks to them, represents them, and inspires them. Limiting art to the viewpoint of any dominant group limits the expression and growth of families. “Drawing the Line” is the catalyst for related questions: Would similar artwork that expressed heteronormative experiences have invited the same controversy? And why is sexuality considered an offensive or inappropriate subject for public artistic display while scenes of conquerors, violence, and dominance are prominently exhibited? Examples of and responses to the latter will be discussed in this chapter.

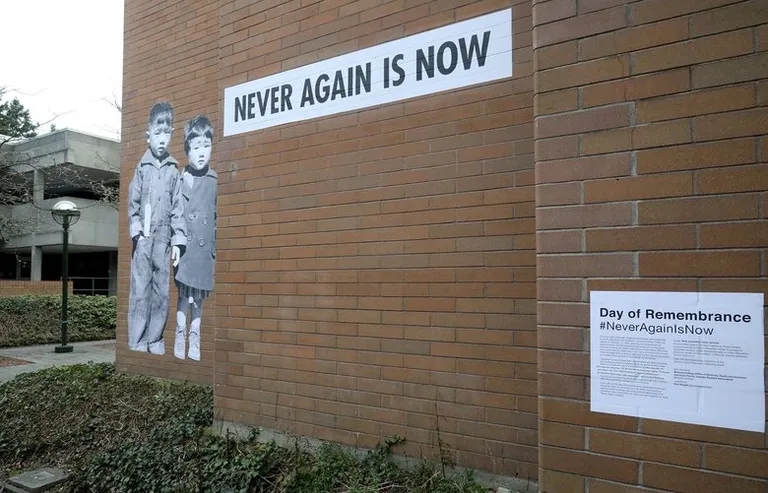

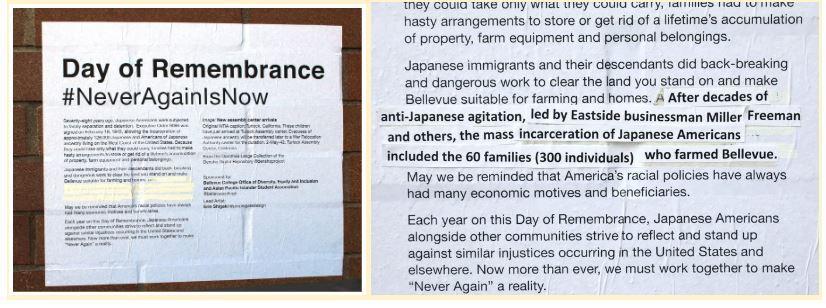

In 2020, another example of public art that led to controversy among stakeholders occurred during a clash at Bellevue College in Seattle, Washington, which counted more than one-fifth of their students and employees as Asian and Pacific Islanders at the time. A mural commissioned to illustrate the unjustness of the imprisonment of Japanese American citizens during World War II (figure 12.12) was brought to campus to recognize the Day of Remembrance, which recognizes the day that President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order that authorized the incarceration.

The artist’s statement revealed factual information that has been documented in newspaper archives and history books about local leader Miller Freeman’s anti-Japanese statements and actions that contributed to the efforts to imprison these citizens. His descendants, who own extensive amounts of property and businesses in the local area, objected to the statement (Cornwell, 2020). Several administrative leaders bowed to pressure to alter the artist’s statement on a public mural (figure 12.13). This is a literal example of whitewashing history, as Wite-Out was used to eliminate the racially/ethnically biased actions of a White businessman.

Later, the whited-out section was replaced with the original words. Ultimately, the administrator who made the decision to white out the words was fired, as was the college president. Artist Erin Shigaki, whose father was born in a Japanese internment camp, wrote to The Seattle Times in response to the covering up of her words, “I had the feelings associated with both sides of my family being forcibly removed from Seattle—erased, unimportant, disregarded, disrespected, shamed” (Cornwell, 2020).

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for Cultural Exposure Can Be Unintentional

Open Content, Original

“Access to Culture Can Be Unintentional” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Christopher Byers. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Linn-Benton Community College and ‘Drawing the Line’” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Protest Art” by Carla Medel. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Public Art” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 12.7. “Mural Portrait of George Floyd by Eme Street Art in Mauerpark (Berlin, Germany)” by Singlespeedfahrer (photographer). License: CC0.

Figure 12.8. Photograph by Pxfuel. License: Pxfuel License.

Figure 12.6. “Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas USA, Architect Moshe Safdie, Photo of One of Three Bridge Pavilions” by Charvex. License: CC0 1.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 12.9. “Rend and Mend” © Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 12.10. “Thresh(strand)hold” © Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 12.11. “…And Then What Will Happen Bent to What Could Happen…” © Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 12.12. “Erin Shigaki’s statement about her installation at Bellevue College is shown after a sentence was removed that references anti-Japanese views held by Miller Freeman and other Eastside businessmen in the decades leading up to…” by Leslie Lum, The Seattle Times. All rights reserved. License: Fair Use.

Figure 12.13. “The sentence removed from Erin Shigaki’s statement accompanying her art installation at Bellevue College has now been replaced” by Greg Gilbert, The Seattle Times. All rights reserved. License: Fair Use.

References

Cornwell, P. (2020, February 26). Bellevue College apologizes after administrator alters display on Japanese American incarceration, The Seattle Times.

Cornwell, P. (2020, March 2). Bellevue College president, vice president out after mural on Japanese American incarceration was altered, The Seattle Times.

Green, J.P., Kisida, B., & Bowen, D.H. (2013, September 16). The educational value of field trips. Education Next, 14(1). https://www.educationnext.org/the-educational-value-of-field-trips/

Guy, S. (2017, October 25). Drawing the line: Artist Andrew Douglas Campbell speaks on behalf of his controversial work. The Linn-Benton Community College Commuter. http://lbcommuter.com/drawing-the-line-artist-andrew-douglas-campbell-speaks-on-behalf-of-his-controversial-artwork/

Kisida, B., Green, J.P., & Bowen, D.H. (2013, November 23). Art makes you smart. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/opinion/sunday/art-makes-you-smart.html

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.

ensuring that people have what they need in order to have a healthy, successful life that is equal to others. Different from equality in that some may receive more help than others in order to be at the same level of success.

a method by which sociologists gather their data by asking questions.

a way of using creative work to communicate used by activists and social movements.

art in any medium whose form, function, and meaning are created for the general public, often through a public process.

can include the emotional significance of an action or way of being; the intention or reason for doing something; something that we create and feel; closely linked to motivation.

the pattern of romantic and/or sexual attraction to others in relation to one’s own gender identity.

being confined within a prison or jail.