14.4 Lifespan Development and Creativity

Elizabeth B. Pearce

In addition to varying by country and culture, purpose and meaning changes based on your lifespan development, according to Westernized views. The psychosocial model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life. The theory emphasizes our relationships and that society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior and the importance of conscious thought. Let’s look at the Erikson’s lifespan model, which identifies developmental tasks that occur from infancy through the last stages of life. This model was developed by Erik Erikson, with his wife Joan, who also added a ninth stage to the model following her husband’s death.

We will also examine views of creativity and spirituality as a part of purpose. You will meet Henry Louis Gates Jr., a literary critic, professor, historian, filmmaker, and the host of Finding Your Roots, in which celebrities examine their ancestral history. Not only can creativity be purposeful and joyful, but it also can be an avenue to cope with oppression or depression.

Lifespan Theory: Adolescence

For the purposes of discussing meaning and purpose, we will start by discussing adolescence. But if you would like a look at the full lifespan model, see the chart in Appendix C. Erikson believed that the primary psychosocial task of the fourth stage, adolescence, was establishing an identity. As formal operational thinking unfolds, bringing with it adolescent self-consciousness and the ability to reflect on one’s own attributes and behaviors, teens often struggle with the question, “Who am I?” This includes questions regarding their appearance, vocational choices and career aspirations, education, relationships, sexuality, political and social views, personality, and interests. Erikson saw this as a period of uncertainty, confusion, exploration, experimentation, and learning regarding identity and one’s life path. Erikson suggested that most adolescents experience psychological moratorium, where teens put on hold commitment to an identity while exploring their options. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research suggests that few leave the adolescent period with identity achievement and that for most of us, the process of identity formation continues all during the years of emerging and young adulthood (Côtè, 2006).

Lifespan Theory: Middle Adulthood

Here, we will focus on the seventh stage or middle adulthood. The Eriksons believed that generativity encompasses procreativity, productivity, creativity, and legacy (Erikson, 1950, 1982). This stage includes the generation of new beings, new ideas or creations, and lasting contributions, as well as self-generation concerned with further identity development. Erikson believed that the stage of generativity, which lasts from the 1940s to the 1960s, during which one established a family and career, was the longest of all the stages. Individuals in midlife are primarily concerned with leaving a positive legacy of themselves, and parenthood is the primary generative type. Much like other scientific theories and measurements, cultural beliefs drove which questions were asked and, thus, which answers were included in social theories. Parenthood and employment were viewed as potentially in conflict due to the obligations of each.

Beyond parenthood and working, Erikson also described generativity as being involved in the community, for example, providing mentoring, coaching, community service, or taking leadership in church or other community organizations. A sense of stagnation occurs when one is not active in generative matters; however, stagnation can motivate a person to redirect energies into more meaningful activities.

Demographic changes since the majority of Erikson’s work was published include declining mortality, with older adults living both longer and healthier lives. Increasingly, older adults who have children and grandchildren are spending more time in the generative stage of caregiving (with grandchildren).

Creativity

Erikson defined the developmental task of generativity as one that included creativity. What do you think creativity is? Perhaps take a second and reflect on cultural monuments, architecture, artworks, music, theater, and literature. Compare the four paintings featured in collage in figure 14.6. Is one of these more creative than the other? If so, what makes one piece more creative than the other?

There are many definitions of creativity, both scientific and non-scientific. Creativity includes:

- Generating original materials

- Solving problems using one’s own or others’ ideas

- Recognizing alternative solutions

- Designing activities that entertain others

Psychologists who study creativity largely agree on three components. First, creativity involves a great deal of divergent thinking, that is, the ability to look at things from different perspectives. Secondly, creativity involves a unique perspective or some element of originality. Finally, creativity must have functionality in that a creative work serves some function or some value. While the paintings display various degrees of originality and divergent thinking, their functionality may not be as transparent as other creative works, such as unique architectural designs.

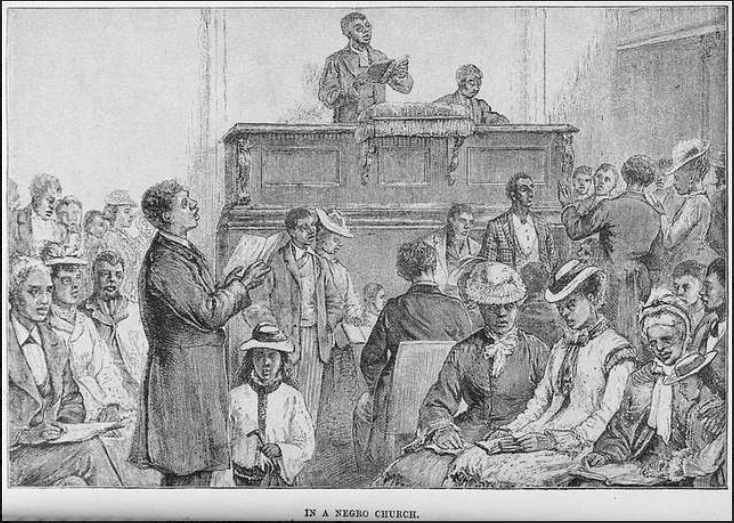

Being creative is also an avenue to overcome depression and despair, which are conditions that can get in the way of finding life meaningful. Black families enslaved in the United States endured great suffering, including having their families torn apart. We know that family is one of the aspects of life that people around the world find meaningful. How did people who were enslaved continue to find meaning in life? One answer is provided via churches and religion, as illustrated in figure 14.7.

While the enslavers thought that religion would help keep Black people subservient, it rather was a place for learning, development, and creativity (Gates, 2021):

The Black church was the cultural cauldron that Black people created to combat a system designed to crush their spirit. Collectively and with enormous effort, they refused to allow that to happen. And the culture they created was sublime, awesome, majestic, lofty, glorious, and at all points subversive of the larger culture of enslavement that sought to destroy their humanity. The miracle of African American survival can be traced directly to the miraculous ways that our ancestors reinvented the religion that their “masters” thought would keep them subservient, Rather, that religion enabled them and their descendants to learn, to grow, to develop, to interpret and reinvent the world in which they were trapped.

Gates describes all of the creative arts that not only took place in the church but also those that centered the Black church life and experience: “music, dance, and song; rhetoric and oratory; poetry and prose; textual exegesis and interpretation; memorization, reading, and writing; the dramatic arts and scripting; call-and-response, signifying, and indirection; philosophizing and theorizing; and, of course, mastering all of ‘the flowers of speech,’” as shown in figure 14.8 (Gates, 2021).

You’ve read several definitions of creativity and viewed some artworks in this short section. What is your viewpoint of what is creative?

Lifespan Theory: Late Adulthood

Erikson framed the last part of the lifespan with the developmental task of Integrity versus Despair. The value of life is negotiated during middle adulthood in the search for meaning and a purpose larger than yourself that will contribute to your legacy (i.e., Generativity). This final task comes down to whether you have built a life and constructed a self that is sufficient to withstand the disintegration of your physical body, the death of many of those you love, and your own impending death with dignity and grace.

Lifespan Theory: Elderly Adulthood

Joan Erikson proposed (from her own experiences and the notes created by Erik and her before his death) that in a ninth state, older adults revisit the previous eight stages and deal with the previous conflicts in new ways as they cope with the physical and social changes of growing old.

People tend to become more involved in prayer and religious activities as they age. This provides a social network as well as a belief system which can combat the fear of death. Religious activities provide a focus for volunteerism and other activities as well. For example, one elderly woman prides herself on knitting prayer shawls that are given to those who are sick. Another serves with the group responsible for keeping robes and linens clean and ready for communion.

The Eriksons found that those who successfully come to terms with these changes and adjustments in later life make headway toward gerotranscendence, a term coined by gerontologist Lars Tornstam to represent a greater awareness of one’s own life and connection to the universe, increased ties to the past, and a positive, transcendent, perspective about life (Tornstam, 1989).

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for Lifespan Development and Creativity

Open Content, Original

Figure 14.6. Creativity collage selected by Liz Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0. Adapted from “Dancing Couple in the Snow” by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, “Stela of Amenemhat and Hemet” by Unknown, “Alfred la Guigne” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and “Who Is Sylvia? What Is She, That All the Swains Commend Her?” by Edwin Austin Abbey. Public domain.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“LIfespan Development and Creativity” is adapted from Identity Development during Adolescence by the Human Development Teaching and Learning Group at Portland State University in Human Development. License: CC BY-NC-SA. Middle Adulthood: Generativity, Intelligence, and Personality and Late Adulthood by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French in “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition.” License: CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: editing for brevity; updating Erikson’s work to integrate demographic changes; creating an excerpt that focuses on generativity, motivation, creativity, integrity, and religion; minor edits for clarity. Additions: a focus on Black religious and creative arts; three images; quotes from Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Figure 14.7. “In a Negro Church” from “America Revisited: From the Bay of New York to the Gulf of Mexico, and from Lake Michigan to the Pacific” by George Augustus Sala in this collection. License: CC0 1.0.

Figure 14.8. “Howard Gospel Choir” by Adam Fagen. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

References

de St. Aubin, E., & Mc Adams, D. P. (1995). The relation of generative concern and generative action to personality traits, satisfaction/happiness with life and ego development. Journal of Adult Development, 2, 99-112.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York: Norton & Company.

FRANKEN C (2001) A.S. Byatt: art, authorship, creativity. Palgrave, Basingstoke, UK.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (2021). The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Havey, Elizabeth A. (2015). “What’s Generativity and Why It’s Good for You.” Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/whats-generativity-and-why-its-good-foryou_b_7629174?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAISJrz_B9ylovtOxRuUNpAiqtA6GZvMM8nUxuyG0eL1AwbMX0F2fEIL6QyV_cF4SYXbn9OyhdIzXtdHB-UwJqn73I0rFzpLKpv35gT

Malone, J. C., Liu, S. R., Vaillant, G. E., Rentz, D. M., & Waldinger, R. J. (2016). Midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development: Setting the stage for late-life cognitive and emotional health. Developmental Psychology, 52(3), 496-508.

Pearce, James (1971). Natural Shapes in Nonobjective Painting: Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Painting.

Peterson, B. E., Smirles, K. A., & Wentworth, P. A. (1997). Generativity and authoritarianism: Implications for personality, political involvement, and parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1202-1216.

Tornstam L. (1989). Gero-transcendence: a reformulation of the disengagement theory. Aging (Milano). 1989 Sep;1(1):55-63. doi: 10.1007/BF03323876. PMID: 2488301.

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.

can include the aim, goal, or intention of an action; a long-term guiding principle; the impact our life has on the world.

can include the emotional significance of an action or way of being; the intention or reason for doing something; something that we create and feel; closely linked to motivation.

a framework that emphasizes our relationships and that society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior and the importance of conscious thought.

a structural framework, explanation, or tool that has been tested and evaluated over time.

the pattern of romantic and/or sexual attraction to others in relation to one’s own gender identity.

a systematic investigation into a particular topic, examining materials, sources, and/or behaviors.

the concern for the future and one’s own contribution to the next generation.

the act of providing support or watching over a person.

the developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult.