2.3 Research Methods and Applications to Studying Families

Elizabeth B. Pearce

Much of what we know about families and kinship comes from research, systematic investigations into a particular topic which examinines materials, sources, and/or behaviors, conducted in the United States and in other countries. In order to be a critical consumer of research, it is helpful to understand what methodologies are used, and what their strengths and limitations are. In addition, it is useful to be aware that there are myths and beliefs that we hold because society has created and reinforced them. When learning new information we must be prepared to question our own long-held beliefs in order to incorporate greater understanding.

Sound research is an essential tool for understanding families. Families are complex because there are multiple ways that families form and function. Every family is composed of unique individuals. Studies about families seek to learn about how families interact internally as well as with the greater social world. What are the effects of actions and environments on families? How do families treat each other within their structures? For example, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted individuals and families in multiple ways, changing most people’s health, social, work, school, and home environments. But how do we understand and quantify those changes? What impacts, dynamics, consequences, and solutions have families experienced?

The table in figure 2.2 briefly describes the major ways scholars gather information, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and a narrative of each method follows.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Survey | Many people can be included. If given to a random sample of the population, a survey’s results can be generalized to the population. | Large surveys are expensive and time consuming. Although much information is gathered, this information is relatively superficial. |

| Experiments | If random assignment is used, experiments provide fairly convincing data on cause and effect. | Because experiments do not involve random samples of the population and most often involve college students, their results cannot readily be generalized to the population. |

| Observation (Field Research) | Observational studies may provide rich, detailed information about the people who are observed. | Because observation studies do not involve random samples of the population, their results cannot readily be generalized to the population. |

| Existing Data | Because existing data have already been gathered, the researcher does not have to spend time and money to gather data. | The dataset being analyzed may not contain data on all the variables in which a sociologist is interested, or it may contain data on variables that are not measured in ways the sociologist prefers. |

Surveys

The survey is the most common method by which sociologists gather their data. The Gallup poll is perhaps the most well-known example of a survey and, like all surveys, gathers its data with the help of a questionnaire that is given to a group of respondents. The Gallup poll is an example of a survey conducted by a private organization, but sociologists do their own surveys, as does the government and many organizations in addition to Gallup. Common survey formats include face-to-face and telephone surveys, as well as internet tools such as Google forms and email.

Many surveys are administered to respondents who are randomly chosen and thus constitute a random sample. In a random sample, everyone in the population (whether it be the whole U.S. population or just the population of a state or city, all the college students in a state or city or all the students at just one college, etc.) has the same chance of being included in the survey. The beauty of a random sample is that it allows us to generalize the results of the sample to the population from which the sample comes. This means that we can be fairly sure of the behavior and attitudes of the whole U.S. population by knowing the behavior and attitudes of just four hundred people randomly chosen from that population.

Surveys are used in the study of families to gather information about the behavior and attitudes of people regarding their behaviors. For example, many surveys ask people about their use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs or about their experiences of being unemployed or in poor health. Many of the chapters in this book will present evidence gathered by surveys carried out by sociologists and other social scientists, various governmental agencies, and private research and public interest firms.

Experiments

Experiments are the primary form of research in the natural and physical sciences, but in the social sciences, they are for the most part, found only in psychology. Some sociologists still use experiments, however, and they remain a powerful tool of social research.

The major advantage of experiments, whether they are done in the natural and physical sciences or in the social sciences, is that the researcher can be fairly sure of a cause-and-effect relationship because of the way the experiment is set up. Although many different experimental designs exist, the typical experiment consists of an experimental group and a control group, with subjects randomly assigned to either group. The researcher does something to the experimental group that is not done to the control group.

As you might imagine, ethical issues emerge rapidly when we think of human beings and family life as the subject of this type of experiment. What if an experiment denied or forbade prenatal care to pregnant women in the control group but provided and encouraged it to another group of pregnant women? So experiments, while useful, are not commonly used to study families.

Observational Studies

Observational research is a staple of sociology. Sociologists have a long history of observing people and social settings, and the result has been many rich descriptions and analyses of behavior in families, schools, gangs, bars, urban street corners, and even whole communities.

Observational studies, also called field research, consist of both participant observation and nonparticipant observation. Their names describe how they differ. In participant observation, the researcher is part of the group that they are studying—they spend time with the group and might even live with people in the group. In nonparticipant observation, the researcher observes a group of people but does not otherwise interact with them. If you went to your local shopping mall to observe whether people walking with children looked happier than people without children, you would be engaging in nonparticipant observation.

Similar to experiments, observational studies cannot automatically be generalized to other settings or members of the population. But in many ways they provide a richer account of people’s lives than surveys do, and they remain an important method of research on social problems.

Analysis and Synthesis of Existing Data

Sometimes, sociologists do not gather their own data but instead, analyze existing data that someone else has gathered. The U.S. Census Bureau, for example, gathers data on all kinds of areas relevant to the lives of Americans, and many sociologists analyze census data on such social problems as poverty, unemployment, and illness. Sociologists and psychologists interested in crime and the criminal justice system may analyze data from court records, while medical researchers often analyze data from patient records at hospitals.

Analysis of existing data such as these is called secondary data analysis. Its advantage to sociologists is that someone else has already spent the time and money to gather the data. If one study does not contain all the data that the researcher needs, they may synthesize data from multiple studies, both quantitative and qualitative, to reach broader conclusions.

Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Research can be qualitative, quantitative, or sometimes both. Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, whereas qualitative research deals with words and with meanings. Both of these kinds of analyses are important for understanding families. For example, quantitative research can tell us how many, or what percentage of families studied, have participated in a social process such as marriage, divorce, or remarriage. Qualitative research can tell us how members of that family experienced the process: what emotional reactions did they have, what did it mean to them, and what other actions or behaviors they attribute to being involved in the specific social process (marriage, divorce, or remarriage). Quantitative research is measurable; qualitative research is descriptive.

The Scientific Process and Objectivity

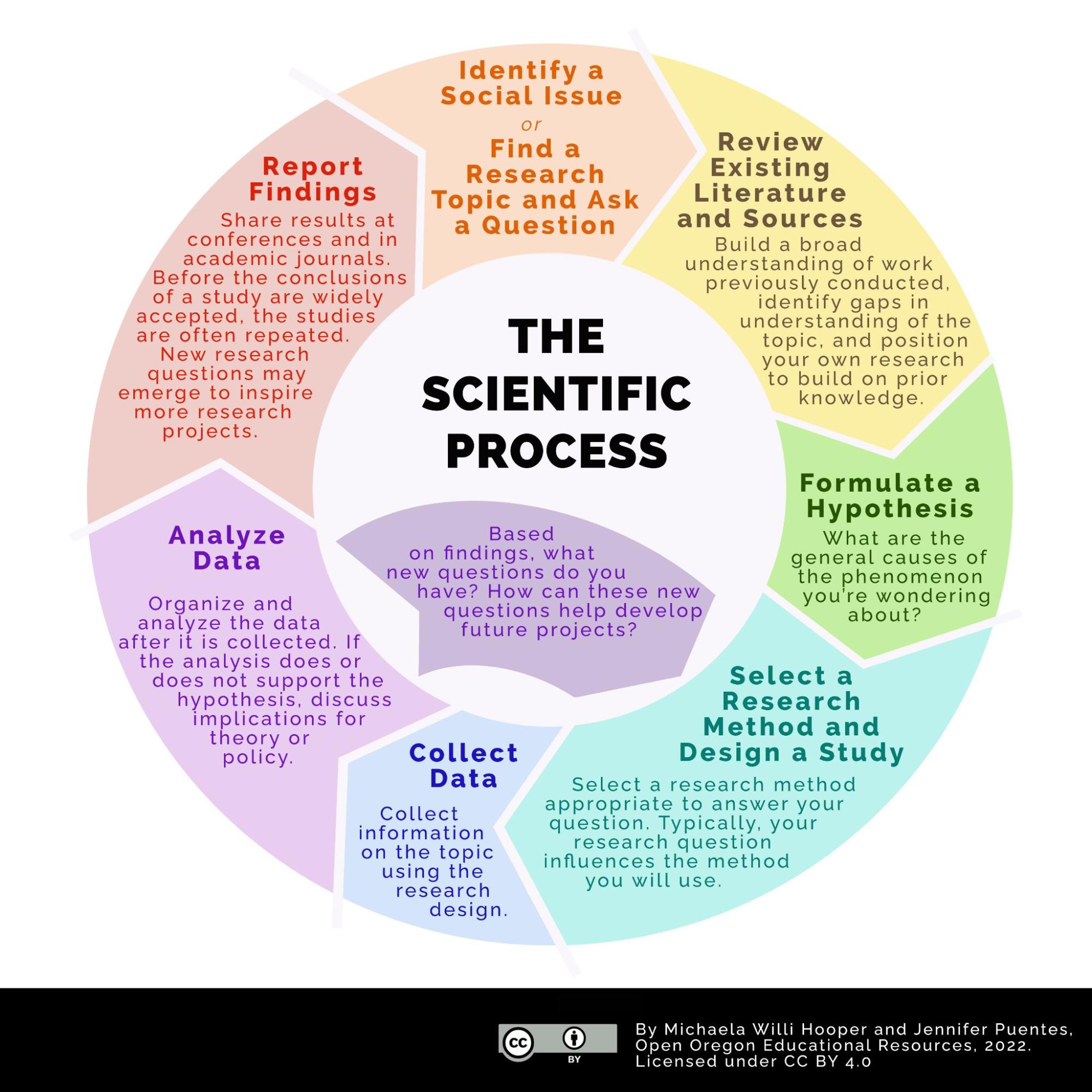

This section began by stressing the need for sound research in the study of social problems. But what are the elements of sound research? At a minimum, such research should follow the rules of the scientific process: formulating hypotheses, making observations, gathering and testing data, drawing conclusions, and modifying hypotheses. These steps, as shown in figure 2.3, help guarantee that research yields the most accurate, descriptive, and reliable conclusions possible.

An overriding principle of the scientific process is that research should be conducted as objectively as possible. Researchers are often passionate about their work, but they must take care not to let the findings they expect and even hope to uncover affect how they do their research. This, in turn, means that they must not conduct their research in a manner that helps achieve the results they expect or desire to find. Such bias can happen unconsciously, and the scientific process helps reduce the potential for this bias as much as possible.

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for Research Methods and Applications to Studying Families

Open Content, Original

Figure 2.3. “The Scientific Process” by Michaela Willi Hooper and Jennifer Puentes, Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Research Methods and Applications to Studying Families” is adapted from “Understanding Social Problems” in Social Problems: Continuity and Change by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations: edited for clarity, brevity, timeliness, and relevance. Addition of graphic image.

Figure 2.2 “Research Methods Table” ” is adapted from “Understanding Social Problems” in Social Problems: Continuity and Change by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations: edited for clarity, brevity, timeliness, and relevance

References

Amato, P. R. (2019). What is a family? National Council on Family Relations. Retrieved December 31, 2019, from https://www.ncfr.org/ncfr-report/past-issues/summer-2014/what-family

Whyte, W. F. (1943). Street corner society: The social structure of an Italian slum. University of Chicago Press

Wright Mills, C. (1959). The sociological imagination. Oxford University Press. Retrieved December 31, 2019, from https://sites.middlebury.edu/utopias/files/2013/02/The-Promise.pdf

the social structure that ties people together (whether by blood, marriage, legal processes, or other agreements) and includes family relationships.

a systematic investigation into a particular topic, examining materials, sources, and/or behaviors.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a method by which sociologists gather their data by asking questions.

a primary form of research in natural and physical sciences that involves comparing and contrasting at least two different interventions.

a type of field research that includes both participant observation and nonparticipant observation.

a population census that takes place every 10 years and is legally mandated by the U.S. Constitution.

concerned with equity, equality, fairness and sometimes punishment.

the study of existing research.

the numbers-based, measurable study of a topic.

the descriptive, in-depth study of a topic.

the process of formulating hypotheses, making observations, gathering and testing data, drawing conclusions, and modifying hypotheses.

the organization of institutions within society; this affects the ways individuals and families interact together.