8.4 Housing Inequities’ Effects on Families

Carla Medel; Katherine Hemlock; Dominic Church; Shonna Dempsey; and Elizabeth B. Pearce

The government and financial organizations both hold substantial power in the United States. Together, they affect how homes are purchased and who can purchase them. Although we know that race is a social construction, it is still used as an identifying feature for families, and it has been used by these systems to control home purchases and to segregate living areas. We will discuss housing from the perspective of racial-ethnic groups affected by these regulations and practices.

While it may be obvious that home ownership increases stability and enables individuals and families to accrue wealth, it is also true that home ownership has a significant effect on the life satisfaction of low-income people. Home buyers have been found to have higher levels of life satisfaction and may also have increased self-esteem and a sense of control compared to renters (Rohe & Stegman, 1994). It is impossible to talk about lower rates of home ownership among minoritized groups without discussing the practices of intentional segregation and gouging enacted by the federal government, lending institutions, local governments, and housing covenants following the legal end of slavery in the United States. Figure 8.8 is an example of signage from this time period.

Redlining

Redlining is the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable or racially occupied. Although homeownership became an emblem of American citizenship and the American dream during the 20th century, Black families and other marginalized populations were specifically limited in their abilities to purchase homes. Both the federal government, which created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933 and the Federal Housing Association in 1934, along with the real estate industry, worked to segregate White neighborhoods from other groups in order to preserve property values.

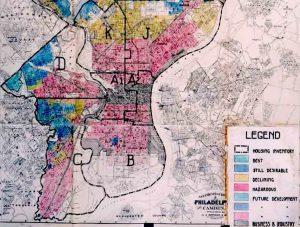

Lending institutions and the federal government did this by creating maps in which the places where people of color and foreign-born individuals lived were colored red (figure 8.9). Then, those areas were designated to be “dangerous” or “risky” in terms of loaning practices. Because families in these same groups were often denied access to the neighborhoods designated to be “good” or “the best,” they were forced to take loans that required higher down payments and/or higher interest rates.

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which regulated home loans, created residential security maps divided into four different categories:

- Green: “The best” for businessmen

- Blue: “Good” for white-collar families

- Yellow: “Declining” for working-class families

- Red: “Detrimental” or “Dangerous” for “foreign-born people, low-class whites, and negroes”

These ratings indicated to lending institutions how “risky” it was to provide loans by area. It was then less likely that loans could be secured in the red and yellow neighborhoods; interest and payments would be higher. Unscrupulous private lenders used this opportunity to create unfair practices such as unreasonably high payments with devastating consequences if one payment or partial payment was missed, such as the Black homeowner losing their home and all equity that had been earned (Coates, 2014).

In 1968, these practices were outlawed by the Fair Housing Act, which was part of the Civil Rights Act. The Fair Housing Act is an attempt at providing equitable housing to all. It makes discriminating against someone based on skin color, sex, religion, and disability illegal. Also banned is the practice of real estate lowballing, where banks underestimate the value of a home, in effect forcing a borrower to come up with a larger down payment to compensate for the lower loan value. The offering of higher interest rates, insurance, and terms and conditions to minority loan applicants is illegal. Denying loans and services on the basis of an applicant’s protected class is also illegal.

Still, much damage was done prior to its passage. For decades, the federal government poured tax monies into home loans that almost exclusively favored White families. Home ownership is the most accessible way to build equity and wealth, and it has been denied to many minority families for decades. Once the Fair Housing Act passed, local governments, residential covenants, and deed modifications continued to discriminate well into the 2000s, and families in marginalized groups still had less success in achieving home loans.

The result of these institutionalized efforts resulted in residential segregation, the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods. Many times, this form of segregation is associated with race, but it can also be associated with income. Segregated neighborhoods did not come about organically but through deliberate planning of policies and practices that have systematically denied equal opportunity to minority populations. Segregation has been present in the United States for many years, and while now it is illegal to do so, it has been institutionalized in neighborhood patterns (figure 8.10). From information collected in the 2010 census, we see that a typical White person lives in a neighborhood that is 75% White and 8% African American, while a typical African American person lives in a neighborhood that is 35% White and 45% African American (Frey, 2020).

In Focus: Residential Segregation in Oregon

As a recipient of federal funding, the city of Portland, Oregon, is required to abide by the rules of the Fair Housing Act, but like many cities in the United States, Portland has a history of redlining and other discriminatory practices. In order to better understand Portland’s practices, learning about Oregon’s history is useful. Black exclusion laws were put in place when the state was founded in order to discourage people of color from settling in Oregon.

Between 1900 and 1930, Portland began zoning practices, the act of separating land based on what it will be used for, such as residential, industrial, and commercial. In 1924, Portland approved its first zoning code with the following zones:

- Zone 1 – Single-Family

- Zone 2 – Multifamily

- Zone 3 – Business-Manufacturing

- Zone 4 – Unrestricted

Most residential areas were designated Zone 2, except for 15 neighborhoods considered the “highest quality” that were designated Zone 1 (Hughes et al., 2019).

Between the 1930s and ’40s, Portland City Council rezoned large areas of multifamily zoning to single-family zoning (figure 8.11). This was done to protect real estate values of single-family homes and make it easier for homeowners to obtain Federal Housing Administration loans in those areas. During this time, roughly 14.25 square miles was rezoned from multifamily to single-family housing. This was used as a tool to further reinforce racial segregation by restricting federal and private lending. It made it difficult, sometimes even impossible, for residents living in “redlined” neighborhoods to receive residential and commercial loans.

Neighborhood planning from 1960 to 1970 included the ideas of residents instead of only the real estate industry. Although many strong neighborhood associations formed, power continued to reside with the more affluent, mostly White neighborhoods, and the 1980 Comprehensive Plan favored expanding and protecting single-family zones.

In 1994, the Community and Neighborhood Planning Program was adopted to address issues that sprouted after the Comprehensive Plan. With this, they did the opposite of what had been done for many years in the past: expanding the multifamily zones. The program sought to expand and intermix multifamily housing, but it was met with resistance and controversy that led to uneven results.

VisionPDX came forward in 2005 as an effort to engage community members, especially those from underrepresented communities, in developing a shared vision of Portland. They wanted to focus on providing an opportunity for input to those who previously had no say in the future of Portland. This new way of thinking about equity led to the development of new goals and policies in the most updated version of the Comprehensive Plan in 2016.

Today, single-family zoning accounts for approximately 74% of the total land area for housing in Portland. Since the 1920s, very little change has occurred with the original 15 single-family zones. These neighborhoods have remained stable and demographically homogeneous with low levels of vulnerability to displacement and tend to be the zones for White households. Similarly, the zones originally designated as less desirable are homes for many families from marginalized groups and contain fewer resources and amenities desired by families.

So what can we learn from this? Portland’s land use planning history, intentional or not, has resulted in discrimination, the unequal treatment of an individual or group, and segregation. These planning practices and the decisions made have predominantly benefited and privileged White homeowners, while communities of color have been burdened, excluded, and displaced. Decision-making for collective improvement is often complicated when it affects individual outcomes. The same people who may believe in equity may also resist change when they perceive that it affects them individually. This is called the “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) phenomenon and likely affected Portland’s failure to move toward creating more mixed neighborhoods. Portland and all cities can do better. Fair housing regulations can be achieved by understanding the history and then creating policy change, which will lead to more equitable outcomes.

Bluelining

Bluelining is a current banking and lending issue related to rising water levels that are a product of climate change. Real estate that is considered high risk due to low elevation and/or proximity to a floodplain may not qualify for loans. With the current rate of ocean warming, sea levels are expected to rise, and warm water will generate storms that will displace millions of people in the United States and worldwide (figure 8.12). “Climigration,” a newly coined word that combines “climate” and “migration,” describes the act of people relocating to areas less devastated by flooding, storms, drought, lack of clean water, or economic disaster due to the forces of climate change.

Many American families relocate as jobs disappear or land becomes flooded or arid. In response to an immediate disaster, many families move to live with relatives or friends. Some families have nowhere to turn. The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment to Congress reported that 3,900 people were staying in sheltered locations specifically for people displaced by presidentially declared national disasters. They were displaced from areas struck by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Nate; Western wildfires; and other storms and events” (Henry et al., 2018).

Climate change has also changed the economic desirability of entire regions, creating a new divide between the poor and the privileged. In the Southern California region of Los Angeles, shade has become an increasingly precious commodity, giving respite from the searing heat that bakes the community during longer, hotter warm seasons.

In the 1950s, the lure of the California sunshine attracted settlers from across the United States to propel LA into a major metropolis. Now, shade provided by large tree-lined neighborhoods and areas of upscale urban design are enjoyed by the affluent but absent for those who need it the most. There is a public health benefit from trees, with studies showing benefits like lower asthma and improved mental health for those exposed to green spaces. The accessibility of green spaces is proving to have a direct impact on health (figure 8.13).

People who live in less desirable neighborhoods and use public transportation also wait at the more than 750 bus stops where police ordered the removal or minimization of trees in an earlier era. To learn about an inventive solution to this problem, read about “Urban Farming: The “Gangsta Gardener” in Chapter 10. They spend more time outdoors, traveling to jobs and needing resources, and suffer the highest heat index (Arango, 2019).

For example, many families live without easy access to recreational trails and playgrounds. Laws, regulations, and lending corporations have actively participated in pushing minoritized racial-ethnic groups into these areas. We must pay attention to these past practices and the ways that they impact present families’ health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear that the virus is transmitted more easily in crowded spaces indoors than in the outdoors (figure 8.14).

There is a disproportionate number of coronavirus cases and deaths among marginalized populations in the United States, and it is possible that lack of access to outdoor spaces plays a role (Godoy & Wood, 2020). Large areas covered in concrete and asphalt, without greenery, contribute to quality of life, as shown in figure 8.15. So at the same time that this lack of resources makes it more difficult to maintain everyday physical and mental health, it may also contribute to illness, hospitalization, loss of employment, and even death during the pandemic.

Environmental Factors Affect Families

Environmental factors, such as proximity to industry and landfills, also affect quality of life. In the U.S., the recycling rate of plastics is only 5% to 6% as of 2021, while at the same time generation of plastic waste per capita has increased by 263% since 1980. While paper, cardboard, and metal are recycled at higher rates, Plastic recycling has never reached 10%. Most of the plastics end up in harmful areas like landfills, incinerators, and areas that were not planned, like waterways (Fox, 2022).

Landfills continue to fill up as we produce more and more plastic waste. Families who make enough money to live in areas with funding for infrastructure can avoid living near landfills and plastic waste. Those who don’t have enough can’t afford to make these choices and end up disproportionately affected by plastics. This includes having to purchase bottled water when tap water is unsafe to buy, as well as living near waste disposal sites (Jones, 2022). Forty percent of the United States’ total landfill capacity and 60% of the largest commercial hazardous waste landfills are in communities that are predominantly families with marginalized identities (Bullard, n.d.).

Change is challenging; those who are faced with the negative consequences of this waste are not the same as those who are benefiting financially. Change is unlikely without economic incentives for corporations to use more easily recyclable and less mixed materials, as it is cheaper to dispose of rather than recycle (STINA, 2021). A federal bill has been proposed: the Environmental Justice for All Act. “This bill establishes several environmental justice requirements, advisory bodies, and programs to address the disproportionate adverse human health or environmental effects of federal laws or programs on communities of color, low-income communities, or tribal and indigenous communities” (Congress, 2022). While promising, this bill has not yet been passed by the U.S. Congress.

In Focus: Reservation Land and Home Ownership

There is another group of families for whom it is more complicated and limited to build capital via home ownership: Native Americans who reside on reservations. When the United States government sequestered Native Americans to reservation lands, it also retained ownership of that land, creating a “ward: guardian relationship” between the government and the Indian Nations, as characterized by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall in 1831 (Cherokee Nations v. Georgia, 1831). The government holds reservation lands “in trust” for the tribal nations.

While there is much public debate about other aspects of tribal rights, such as casinos and the effects of using Native American imagery and names for sports teams, there is little discussion at the legislative level about the ways the U.S. government has limited the abilities of Native Americans to own property within the communities where they live (Schaefer Riley, 2016). This most basic way of building equity in a country that values individualism and capitalism has been restricted to the people who have inhabited it the longest. Native Americans have the highest poverty rate of any racial-ethnic group (28% in 2015), and it is likely that the control the government has exerted over their living conditions contributes to this circumstance (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for Housing Inequities’ Effects on Families

Open Content, Original

“Housing Inequities Effects on Families” and all subsections except those noted below by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Carla Medel, Katherine Hemlock, and Shonna Dempsey. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Residential Segregation in Oregon” by Carla Medel. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Environmental Factors Affect Families” by Dominic Church. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Reservation Land and Home Ownership” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.12. “Economic & Environmental Irony” by Kate Hemlock. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.8. “Sign: ‘We Want White Tenants in our White Community’” by Arthur Siegel/Office of War Information. Public domain.

Figure 8.9. “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Philadelphia redlining map.” Public domain.

Figure 8.11. “Food carts – Portland, Oregon, USA” by Daderot. License: CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Figure 8.13. “Green spaces (4)” by Anthony O’Neil. License: CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 8.14. “COVID-19: Physical Distancing in Public Parks and Trails” © National Recreation and Park Association. Image used with permission.

Figure 8.15. “LA Metro 200 bus stop on Alvarado Street” by Downtowngal. License: CC BY-SA 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Why Cities Are Still So Segregated” © NPR. License: Standard YouTube License.

References

Affordable Housing Online. (n.d.). Search low income apartments and wait lists. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://affordablehousingonline.com/

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Labeling theory. In The APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://dictionary.apa.org/labeling-theory

Arango, T. (2019, December 1). Why shade Is a mark of privilege in Los Angeles. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/01/us/los-angeles-shade-climate-change.html

Cherokee Nations v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)

Coates, T. (2014, June). The case for reparations. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

Environmental justice for All-Bullard – University of Kentucky. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://www.uky.edu/~tmute2/GEI-Web/password-protect/GEI-readings/Bullard-Environmental%20justice%20for%20all.pdf

Fox, E. (2022, May 4). New report reveals that U.S. plastics recycling rate has fallen to 5%-6%. Beyond Plastics – Working To End Single-Use Plastic Pollution. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://www.beyondplastics.org/press-releases/the-real-truth-about-plastics-recycling

Frey, W. H. (2020, March 30). Even as metropolitan areas diversify, White Americans still live in mostly White neighborhoods. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/even-as-metropolitan-areas-diversify-white-americans-still-live-in-mostly-white-neighborhoods/

Henry, M., Mahathey, A., Morrill, T., Robinson, A., Shivji, A., & Watt, D. (2018, December). The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2018-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

Hughes, J. (2019, September). Four of these neighborhoods are shown in figure 8.9. Historical context of racist planning: A history of how planning segregated Portland. Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. City of Portland, Oregon. https://beta.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-12/portlandracistplanninghistoryreport.pdf

Jones, V. (2010, November). The economic injustice of plastic. TEDx. https://www.ted.com/talks/van_jones_the_economic_injustice_of_plastic/transcript?language=en

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2019, June 9). The Equality Act: What transgender people need to know. https://transequality.org/blog/the-equality-act-what-transgender-people-need-to-know

Nelson, R. K. & Winling, L, (2023). Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. University of Richmond. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/

Rohe, W. M., & Stegman, M. A. (1994). The effects of homeownership: On the self-esteem, perceived control and life satisfaction of low-income people. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975571

Schaefer Riley, N. (2016, July 30). One way to help Native Americans: property rights. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/07/native-americans-property-rights/492941/

STINA. (2021). Assessing the State of Food Grade Recycled Resin in Canada & the United States. Assessing the State of Food Grade Recycled Resin in Canada & the United States. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from www.plasticmarkets.org.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2015, November 2). Facts for Features: American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month: November 2015. https://www.sprc.org/resources-programs/us-census-bureau-profile-america-facts-features-american-indian-and-alaskan

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). Housing Choice Voucher Program (Section 8). Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.hud.gov/topics/housing_choice_voucher_program_section_8

Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). Building dignity: Design strategies for domestic violence shelter. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://buildingdignity.wscadv.org/

the categorization of humans using observable physical or biological criteria, such as skin color, hair color or texture, facial features, etc.

meaning assigned to an object or event by mutual agreement (explicit or implicit) of the members of a society; can change over time and/or location.

a person who does not own their place of living but pays another party to live in their place of living.

the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable or racially occupied.

ensuring that people have what they need in order to have a healthy, successful life that is equal to others. Different from equality in that some may receive more help than others in order to be at the same level of success.

an act that protects people from discrimination when they are renting or buying a home, getting a mortgage, seeking housing assistance, or engaging in other housing-related activities.

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes and internal/external reproductive organs.

the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods.

the unequal treatment of an individual or group on the basis of their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex).

real estate that is considered high risk due to low elevation and flooding due to climate change may not qualify for loans.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.

an intersectional social movement pioneered by African American, Indigenous, Latinx, female, lower-income, and other people from historically oppressed populations fighting against environmental discrimination within their communities and across the world.

concerned with equity, equality, fairness and sometimes punishment.

a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and some sense of identity of belonging to the subgroup.

a population census that takes place every 10 years and is legally mandated by the U.S. Constitution.

housing that can be accessed and maintained while paying for and meeting other basic needs such as food, transportation, access to work and school, clothing, and health care.

a structural framework, explanation, or tool that has been tested and evaluated over time.

a systematic investigation into a particular topic, examining materials, sources, and/or behaviors.

individuals who do not identify with the gender they were assigned at birth.

supplied by the government or other public entity for families to use to offset the cost of a private school.