9.3 Macro-Level and Micro-Level Factors Related to Safety

Alexandra Olsen and Dio Morales

As we’ve already noted, the level of safety that an individual or family experiences is directly related to macro-level factors: policies, institutions, community, and cultures. These factors are crucial in creating social support so families can access the resources they need: food, water, health care, money, and others.

In this section, we explore two critical ideas related to macro-level factors. First, we will discuss how social support can increase families’ physical and mental safety. Finally, we will examine how the interconnections between various macro-factors promote safety.

Similar to our discussion of macro-factors, the micro-factors that create safety are also important for families to truly feel secure. This section explores the role of quality relationships in creating safety for families. Together, these factors help families have physical, psychological, spiritual, and communal safety.

Social Supports that Increase Safety for Families

How do society and institutions support or get in the way of families getting what they need? Public policies that expand social support are essential to increasing families’ physical, psychological, spiritual, and communal safety.

For example, let’s look at how the passage of paid parental leave policies promotes and creates safety within families. Paid parental leave policies provide parents time off of work while still receiving their salary after giving birth or following an adoption or foster care placement. The period of parental leave varies from four to 85 weeks, depending on the state or country.

Parental leave policies support families in their physical, psychological, and spiritual safety. Paid parental leave increases the physical safety of members of the family. If a parent gives birth, they have time off to physically recover. The child gains valuable time to bond and be physically close to their parents, which is crucial to developing healthy attachment and psychological safety. The ability to stay home and bond with their child without worrying about whether they’ll be able to pay their bills also provides parents with a sense of psychological safety. Parents have a sense of spiritual safety because of paid parental leave. They feel like society at large acknowledges and understands the demands of a new family member by providing this benefit.

Together, all of these forms of safety increase communal safety. Public policies that create safety help children develop a sense of belonging and attachment to their families. Parental leave is one of many examples of how good public policy can give families a deeper and more comprehensive sense of safety in the short and long term.

Unfortunately, the relative lack of social support for families and individuals in the United States is a major barrier to families getting what they need and creating a true sense of safety. From the earliest stages of life, comprehensive policies are absent to support families.

Safety Nets

While we looked at the example of how families can have a greater sense of safety from paid parental leave, these policies are not universally accessible in the United States. In fact, as of 2021, only nine states and Washington, D.C., have paid parental leave laws, which range from 4 to 12 weeks off and provide anywhere between 50% and 100% of a parent’s pay (KFF, 2021). Similarly, only 35% of all U.S. employees have employers who offer paid parental leave. Most of these employees are in the top 25% of all income earners. These statistics show that the private sector is not compensating for the lack of federal or state laws guaranteeing these benefits (KFF, 2021).

A “safety net,” or safeguard that protects families from hardships, becomes even more important when a country lacks social supports such as parental leave or universal health care. A safety net provides services such as housing or food assistance to families who need it. The lack of publicly funded family health programs, as well as a very limited safety net in the United States, has consequences for families, particularly low-income families in states without these protections.

This lack of a robust social safety net continues to impact families over time, which we can see, for example, when looking at the state of anti-poverty programs in the United States. The U.S. minimum wage remains well below what is required to adequately provide for a family as the cost of living continues to increase. Social safety nets have consistently been cut or are under threat.

Welfare reform in the 1990s is an example of cuts to social programs. Congress changed laws to limit the length of time families could receive this kind of assistance. Another example is the more recent (unsuccessful) attacks on food assistance programs (Hsu, 2020). Many families remain in poverty despite the efforts of remaining social programs—especially when looking at families headed by single mothers or members of oppressed groups.

Poverty impacts every aspect of family life, affecting the family’s physical, psychological, spiritual, and community safety. These issues highlight one of the main reasons representation is important. (See Chapter 6 for more about representation.) If the issues faced by a diverse range of families are not being represented or heard by lawmakers, then families and groups won’t have their needs met. And, if families and groups don’t have their needs met, then safety remains elusive.

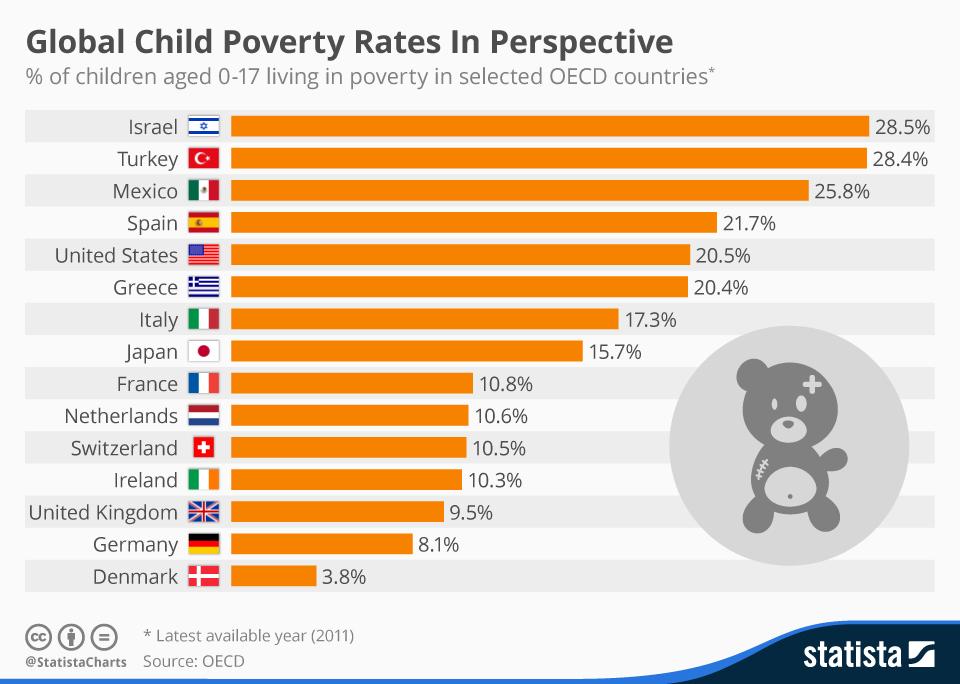

Unlike in the United States, robust social support for families is the norm globally, especially in other high-income nations. For instance, the United States and Papua New Guinea are the only two countries without paid parental leave laws. If we look at other issues, such as child poverty, the United States has higher rates than many other high-income nations, as shown in figure 9.3. Researchers have consistently found that the United States underinvests in its children and families compared to other wealthy countries. This underinvestment leads to negative economic and educational outcomes (Smeeding & Thévenot, 2016).

In these other wealthy countries, we can see how policies such as cash support and employment assistance help groups disproportionately likely to be in poverty in the United States, such as single mothers. If America wants to increase safety within families and communities, it is worth considering what we can learn from the examples of other nations that have increased social support for families.

Interconnection of Macro-Level Safety Factors

A central question addressed in this textbook is, “What do families need?” In answering that question, we examine various aspects of society that contribute to safety. In earlier chapters, we’ve discussed several macro-factors that promote safety in families:

- Chapter Five discusses communities of belonging;

- Chapter Seven highlights access to quality physical and mental health care; and

- Chapter Eight focuses on affordable and safe housing.

In the following chapters, we’ll expand upon this by looking at the ways that access to food (Chapter 10) and water (Chapter 10) and equal justice (Chapter 11) contribute to physical safety and improve the health and wellness of families. At the same time, they give families a deeper sense of agency, belonging, and respect that positively impacts psychological, spiritual, and communal safety.

In many ways, true safety is created when families have all of their needs met. Yet, this can be difficult because many of these needs are related. For instance, it is unlikely that a family in the United States will have access to quality health care, quality education, or affordable and safe housing if they are struggling economically. In many ways, the most privileged members of society have the greatest access to safety. This is because they can get the majority (if not all) of their needs met. Still, many of these factors are interrelated. Consequently, even a modest increase in meeting one of these needs can increase the safety of a family. For instance, increasing access to healthy food and clean water for young children can improve physical and mental health outcomes and educational outcomes.

There are plenty of examples of how families and communities mobilize available resources to create safety, even when they lack other necessary resources or equal protection. Chosen families, often created in LGBTQIA+ communities, as shown in figure 9.4, are a great example. In chosen families, members create a culture that centers around sharing resources. This cooperation can help to compensate for the lack of access to representation in government, equal justice, quality health care, and equal opportunities in the labor market. These practices, in turn, create an improved sense of physical, psychological, spiritual, and communal safety amongst participants—even though society may not be broadly safe or welcoming.

Quality Relationships

Micro-factors are equally important in establishing a sense of safety in families. Quality relationships with family and community members (friends, mentors, coaches, colleagues) are important for children and adults. Families need a sense of safety with one another. They also need a broader sense of security that develops through positive connections with people in their social sphere.

Childhood and adolescence are periods where youth can benefit from positive social relationships. In Chapter Four, we look at the concept of nurturance, highlighting how parenting and caregiving can be important responsibilities taken on within families. Baumrind’s parenting styles strongly argue that the authoritative parenting style can help create safety for children.

In Focus: Learning to Catch Each Other

Twenty-five years ago, I met my husband at Smith Rock State Park. Since then, we have rock-climbed with our kids all over the world. One of our safety devices is a GriGri, which a belayer uses to catch a climber if they fall (figure 9.5). Being tied to your loved ones with a rope and protecting their physical safety with this hand-sized piece of metal is a powerful responsibility. Some of our best conversations with our kids are on these trips, but we usually aren’t talking about the climbing routes; we talk about everything else in our lives. The connection we feel as a family is a big part of what makes the GriGri work.

Children need supportive, emotionally responsive parents who clearly explain and consistently enforce fair rules. When parents do this, it creates a sense of safety by providing children with psychological safety. Children know what to expect if they break the rules. They also generally feel connected to and supported by their parents, trusting their parents will openly communicate with them. Fair rules also create a sense of spiritual safety where children know their parents will treat them with respect. These aspects work together to provide children with communal security—a sense of belonging within their families.

The research on attachment theory, also discussed in Chapter 4, similarly connects back to the idea of safety. For children to have a secure attachment, an indicator that they feel safe, parents need to be able to help children regulate their emotions. Regulation of emotions also helps children to feel deep or unconditional love from their caregivers. Children know they will be supported and safe within their relationship with their caregiver.

Finally, children and adolescents need relationships outside of the family. Many of the PACEs for youth are related to being involved in groups where they can develop friendships and engage with mentors. This is one of the reasons that mentoring programs, such as Big Brothers Big Sisters, have been so effective. These programs have been successful in helping youth stay in school, avoid contact with the juvenile justice system, and build friendships within the communities. Relationships outside the family allow youth to broaden their sense of safety by helping them find new places where they can experience physical, psychological, and spiritual safety. These experiences can give youth a broader sense of communal safety. These experiences also give children a sense of connection to a much wider culture than they could get in their immediate social networks.

Adults within families also need quality relationships with family to have a sense of safety—whether these families are biological or chosen. Relationships outside the family provide adults with a broader sense of connection to their communities, creating a deeper sense of communal safety. At the same time, issues can arise in families—such as intimate partner violence (IPV) or economic struggles—where external support is even more crucial. When families experience problems like this, connections to those outside of the family can help provide members with physical, psychological, and spiritual safety. This kind of safety can be crucial to families getting through tough times or helping them adjust after traumatic events.

Still, the broader social context influences many of these micro-level factors. For instance, it may be harder for a parent to develop a secure attachment to their child if they immediately have to return to work due to lack of paid parental leave. Similarly, while being involved in extracurricular activities and mentoring programs can significantly benefit youth, these activities and programs are not universally accessible. In both examples, it is clear that social supports have a tremendous impact on the level of safety experienced by families.

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for Macro-Level and Micro-Level Factors Related to Safety

Open Content, Original

“Macro-Level and Micro-Level Factors Related to Safety” by Alexandra Olsen. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Learning to Catch Each Other” by Dio Morales. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 9.5. By Dio Morales. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.3. “Global Child Poverty Rates in Perspective” by Niall McCarthy. License: CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.4. “Capital Trans Pride Washington, DC USA 5125” by Ted Eytan. License: CC-SA-2.0.

References

Hsu, S. (2018, October 18). Federal judge strikes down Trump plan to slash food stamps for 700,000. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/legal-issues/trump-food-stamp-cuts/2020/10/18/7c124612-117a-11eb-ad6f-36c93e6e94fb_story.html.

KFF. (2021, December 17). Paid Leave in the US. Women’s Health Policy. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/paid-leave-in-u-s/.

Smeeding, T., & Thévenot C. (2016). Addressing Child Poverty: How Does the United States Compare With Other Nations? Academic Pediatrics, 16(3 Suppl), S67–S75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.011.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

the description or portrayal of someone or something in a particular way.

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.

concerned with equity, equality, fairness and sometimes punishment.

nonbiological kinship bonds, whether legally recognized or not, deliberately chosen for the purpose of mutual support and love.

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.

the act of providing support or watching over a person.

usually refers to Baumrind’s four styles of parenting, which include authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved.

a systematic investigation into a particular topic, examining materials, sources, and/or behaviors.

the theory that the capacity to form emotional attachments to others is primarily developed during infancy and early childhood.

the previous name for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, a federal program that provides food-purchasing assistance for low- and no-income people.