14.2 What Do We Mean by “Meaning”?

Elizabeth B. Pearce and Matthew DeCarlo

Throughout this text we have discussed equity and inclusion through the lens of what families need. We’ve focused on the ways that social structures can facilitate or create barriers for families, based on the ways that social identities are constructed. Some of the needs we’ve discussed are material, such as food and shelter. We’ve looked at loving and connecting relationships and tangible feelings of belonging, representation as well as visual culture that affirms and supports families. This chapter will focus on something less definable: the feelings of meaning and purpose that individuals and families experience. We will also look at the structures and experiences that support or create barriers to families’ purpose and meaning.

Everyone has their own sense of meaning and purpose. One might describe meaning and purpose as being the same thing, while others may see them as different but related concepts. Each word is sometimes used to define the other—for example, this definition of meaning: “Meaning in life reflects the feeling that one’s existence has significance, purpose, and coherence” (Routledge & FioRito, 2021). Or this definition of purpose: “Purpose is the culmination of meaningful goals” (Miller, 2021).

Purposive action can be narrowly defined as exchanging one set of circumstances for a better one. Of course, this does not tell you why someone completed an action—just that you assume they did so for some reason. When we talk about purpose and action in this chapter, we are using a defining purpose as something that drives your spiritual, psychological, and social life.

As you read this chapter, consider the definitions above, as well as these bullet points.

Meaning can include:

- The emotional significance of an action or way of being

- The intention or reason for doing something

- Is something that we create and feel; it’s closely linked to motivation

Purpose can include:

- The aim, goal, or intention of an action

- A long-term guiding principle

- The impact our life has on the world

Activity: Meaning in Life Questionnaire

For a scientific look into your own sense of meaning and purpose in life and how it relates to your health, take a minute or two and complete the “meaning in life” questionnaire.

While there are many potential definitions for “meaning,” this questionnaire conceptualizes meaning as having two components: presence and search.

The “presence of meaning” subscale measures how fully respondents feel their lives are of meaning. Questions 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9 provide five scientific questions that probe the presence of meaning in your life. If you scored highly on questions 1, 4, 5, and 6, you perceive your life to be full of meaning. If you scored highly on question 9, you perceive your life to have less meaning.

According to a recent review of the literature, the presence of meaning is positively related to well-being, intrinsic religiosity, extraversion, and agreeableness and negatively related to anxiety and depression. Presence relates to personal growth, self-appraisals, and altruistic and spiritual behaviors (King & Hicks, 2021).

The other questions in the “meaning in life” questionnaire measure the search for meaning or how engaged and motivated respondents are in efforts to find meaning or deepen their understanding of meaning in their lives. Questions 2, 3, 7, 8, and 10 explored your search for meaning, and if you scored highly on them, you are more engaged with finding meaning in your life.

The search for meaning does not always lead to positive outcomes. Research demonstrates that the search for meaning is associated with negative outcomes such as rumination, negative and fatalistic thoughts about the past and future, negative affect, depression, and neuroticism. Nevertheless, people who report a high sense of meaning in life appear to be better off than others (King et al., 2016; Steger, 2012). According to King and Hicks (2021), higher meaning in life is associated with improved health outcomes as varied as cardiovascular disease, mortality, age-related cognitive decline, and risk for Alzheimer’s disease, burnout, social appeal, psychological disorders, physical disability, and suicidal ideation (p. 564).

Meaning, Belonging, and Kinship

Where do meaning and purpose fit in the discussion of what families need? This section will introduce you to several ideas about meaning and purpose.

Where Does Meaning Fit in a Needs Hierarchy?

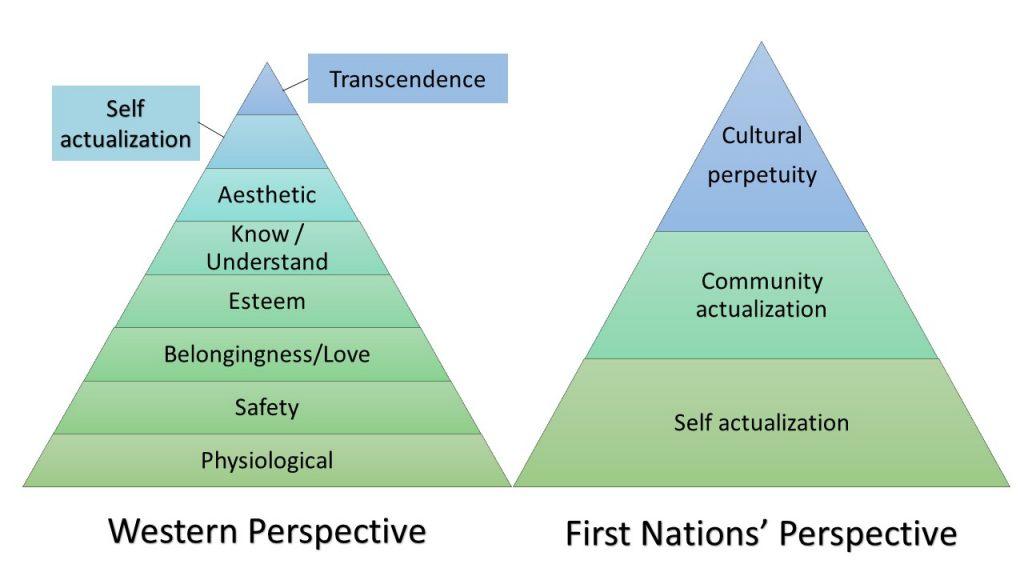

There is a well-known HON model designed by Abraham Maslow, but his work was inspired by his visit with the Blackfoot (Siksika) Indians in Canada in 1938. While Maslow’s model was recorded, it was not as typical then for Indigenous communities to record and publicize their ideas in written form. So, let’s start here with some of the foundational ideas about the needs of the Blackfoot people by re-examining the graphic in figure 14.1.

Self-actualization, or the realization of one’s potential and purpose, is important in part because it contributes to the community’s overall actualization or fulfillment. The highest form that can be attained is cultural perpetuity, which connects kinship, generations, multiple dimensions of time, and meaning. Maslow’s model puts self-actualization at the highest level, whereas in the Blackfoot thinking, self-actualization actually helps the community become its most connected and realized (Bray, 2019).

Cultural perpetuity has been called the “Breath of Life” by Gitskan scholar Cindy Blackstock, who said, “It’s an understanding that you will be forgotten, but you have a part in ensuring that your people’s important teachings live on” (Bray, 2019). Indigenous thinking emphasizes the multidimensional aspect of time and of generations.

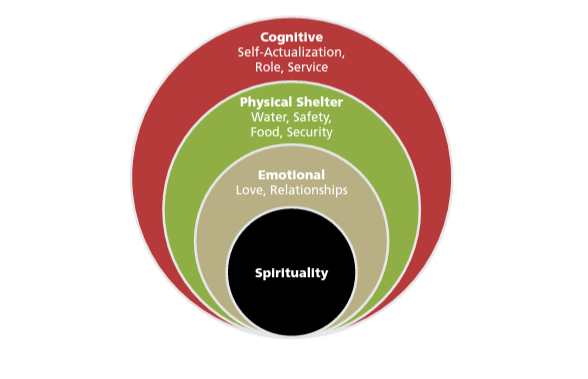

The tipi visualization has been reimagined by Native American scholar and child welfare expert Terry Cross, who seeks to infuse Maslow’s model with Indigenous thinking. He believes that a model that reflects the interdependence of human needs with cultural laws and values is more representative of Indigenous views than a hierarchical model (Blackstock, 2011). This model, figure 14.2, of nested circles reflects the ways that spirituality, relationships, connections, and self-actualization, all aspects of life that can give families meaning or purpose, are nested within one another (Blackstock, 2009).

The HON model, however, shows that a person must meet one need first before achieving another, with self-actualization and transcendence only possible when other needs have been achieved first. Maslow’s writings were reinterpreted by management consultants in the 1960s away from a ladder—on which people can move up and down and hold many rungs at a time—and toward a pyramid—a common hierarchical symbol in management and organizational practice with the CEO on top and workers on bottom. Unlike the textbooks that relied on this reinterpretation, if one engages with his original writings, “Maslow did not say that the HON is unidirectional, that achieving higher levels makes you a superior being, that once a need is satisfied it no longer affects behavior, or that it applies to all people in the same way (Maslow, 1943, 1954)” (Bridgman et al., 2021, p. 92). Over its life span as a theory, our culture’s individualism and ethnocentrism have erased the communal, culturally responsive, and flexible elements of Maslow’s framework.

Both Maslow’s and the Blackfoot models show us that being human is not just about the functions of our physical bodies, or the attainment of material goods. They emphasize the value and importance of what we might call “meaning”—the ways we think about ourselves, the ways we contribute to our kinship groups and community, and how we are a part of future generations. As individuals and families, our purposes in life may vary widely—and the way we think about that purpose will vary as well. However, scholars agree that the intangibles of meaning and purpose, whichever words we may use, are not only a part of being human but also a fundamental need (Routledge & FioRito, 2021).

Finding Meaning

Maslow’s HON also had roots in the humanistic psychology movement, which focuses on human potential and growth. Existential psychologists are deeply concerned with individuals and the conditions of each unique human life. Existential psychology differs significantly from humanistic psychology. However, in focusing on present existence and the concerns with death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness that are so often associated with the circumstances of our lives (Lundin, 1979). The difference can easily be seen in the titles of two influential books written by leading existential psychologists: Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl (1946/1992) and Man’s Search for Himself by Rollo May (1953).

Both Viktor Frankl and Rollo May were immersed in existential thought and its application to psychology when they faced seemingly certain death. For Frankl, who was imprisoned in the Nazi concentration camps, death was expected. For May, who was confined to a sanitarium with tuberculosis, death was a very real possibility (and indeed, many died there). In this text, we will focus on Frankl’s work.

In Focus: Love, Family, and Meaning

Watch the video in figure 14.3 about Frankl’s main ideas from Man’s Search for Meaning.

As you watch this video, watch for this well-known quote about Frankl’s wife, who died in a different camp (Frankl, 1992):

I did not know whether my wife was alive, and I had no means of finding out but at the moment it ceased to matter. There was no need for me to know; nothing could touch the strength of my love, my thoughts, and the image of my beloved. Had I known then that my wife was dead, I think that I would still have given myself, undisturbed by that knowledge, to the contemplation of her image, and that my mental conversations with her would have been just as vivid and just as satisfying. “Set me like a seal upon thy heart; love is as strong as death.”

Listen to other ways in which love, belonging, and family are considered to be a part of meaning in life. Ask yourself how family and belonging have or have not helped you to find meaning and purpose in life.

To explore the topics of familial death, grief, and meaning more deeply, use the podcast and questions in the “Grief and Meaning” activity in the “Going Deeper” section.

Contributions to Families’ Well-Being

Purpose and meaning have also been linked to positive physical and mental health in undergraduates, older adults, adolescents, middle-aged adults, cancer patients, and African Americans. In a national study, African Americans who felt that their lives had meaning tended to have fewer depressive symptoms and a positive effect. This appeared to be independent of stress levels, although both income (higher) and gender (women) seemed to have the strongest positive effects (Park et al., 2020).

In this chapter, we will examine the ways in which scholars have studied purpose and meaning. We will look at “Westernized” views, those that have most often emerged and been emphasized in European countries, the United States, and Canada. We will examine Indigenous views related to meaning and purpose, the barriers to realizing meaning and purpose, and the ways that those barriers relate to defining what makes life most meaningful. We will highlight the connection of a meaningful life and kinship, family, and community.

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for What Do We Mean by “Meaning”?

Open Content, Original

“What Do We Mean by Meaning?” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Matthew DeCarlo. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Meaning of Life Questionnaire” by Matthew DeCarlo. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Love, Family, and Meaning” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Contributions to Families’ Well-Being” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 14.1. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and First Nations’ perspective.” License: CC BY 4.0. Based on a slide created by Cindy Blackstock that appears in Maslow’s Hierarchy Connected to Blackfoot Beliefs by Karen Lincoln Michel and Rethinking Learning by Barbara Bray.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Finding Meaning” is adapted from “Personality Theory” by Mark Kelland. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: excerpting two paragraphs; shortening for brevity.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.2 “Figure 6: Cross (2007) Maslow through Indigenous eyes” by Cindy Blackstock in When Everything Matters: Comparing the experiences of First Nations and Non-Aboriginal children removed from their families in Nova Scotia from 2003 to 2005 (p.37). License: Fair Use.

Figure 14.3 Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl by One Percent Better. License: Standard YouTube License.

References

Blackstock, C. (2009). When Everything Matters: Comparing the Experiences of First Nations and non-Aboriginal Children Removed from their Families in Nova Scotia from 2003 To 2005, Factor Inwentash School of Social Work, University of Toronto.

Blackstock, C. (2011). The Emergence of the Breath of Life Theory. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 8(1).

Bray, B. (2019). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and blackfoot (Siksika) nation beliefs—Rethinking learning. (2019, March 10). https://barbarabray.net/2019/03/10/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-and-blackfoot-nation-beliefs/

Bridgman, T., Cummings, S., & Ballard, J. (2019). Who built Maslow’s pyramid? A history of the creation of management studies’ most famous symbol and its implications for management education. Academy of management learning & education, 18(1), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2017.0351

Cohen, R., Bavishi, C., & Rozanski, A. (2016). Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic medicine, 78(2), 122-133. DOI: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274

Frankl, V.E. (1992). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy (4th ed.).

Miller, M. (2021, March 29). Goals, purpose and meaning: What’s the difference? Six Seconds. https://www.6seconds.org/2021/03/29/goals-purpose-and-meaning/

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual review of psychology, 72, 561-584.

Lundin, R. W. (1979). Theories and systems of psychology (2nd edition). Heath.

Park, C. L., Knott, C. L., Williams, R. M., Clark, E. M., Williams, B. R., & Schulz, E. (2020). Meaning in life predicts decreased depressive symptoms and increased positive affect over time but does not buffer stress effects in a national sample of african-americans. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(8), 3037–3049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00212-9

Routledge, C., & FioRito, T. A. (2021). Why meaning in life matters for societal flourishing. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601899

ensuring that people have what they need in order to have a healthy, successful life that is equal to others. Different from equality in that some may receive more help than others in order to be at the same level of success.

the description or portrayal of someone or something in a particular way.

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.

can include the emotional significance of an action or way of being; the intention or reason for doing something; something that we create and feel; closely linked to motivation.

can include the aim, goal, or intention of an action; a long-term guiding principle; the impact our life has on the world.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a systematic investigation into a particular topic, examining materials, sources, and/or behaviors.

the developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult.

the social structure that ties people together (whether by blood, marriage, legal processes, or other agreements) and includes family relationships.

a structural framework, explanation, or tool that has been tested and evaluated over time.

an approach that focuses on the “whole” person and the major concerns of death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness.

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.

a socially constructed expression of a person’s sexual identity which influences the status, roles, and norms for their behavior.