5.3 Traditions and Rituals

Monica Olvera

In the previous section, we examined the implications of family routines for family well-being. In this section, we will discuss the differences between routines and rituals, the importance of rituals and traditions for families, and examples that describe important life events and transitions.

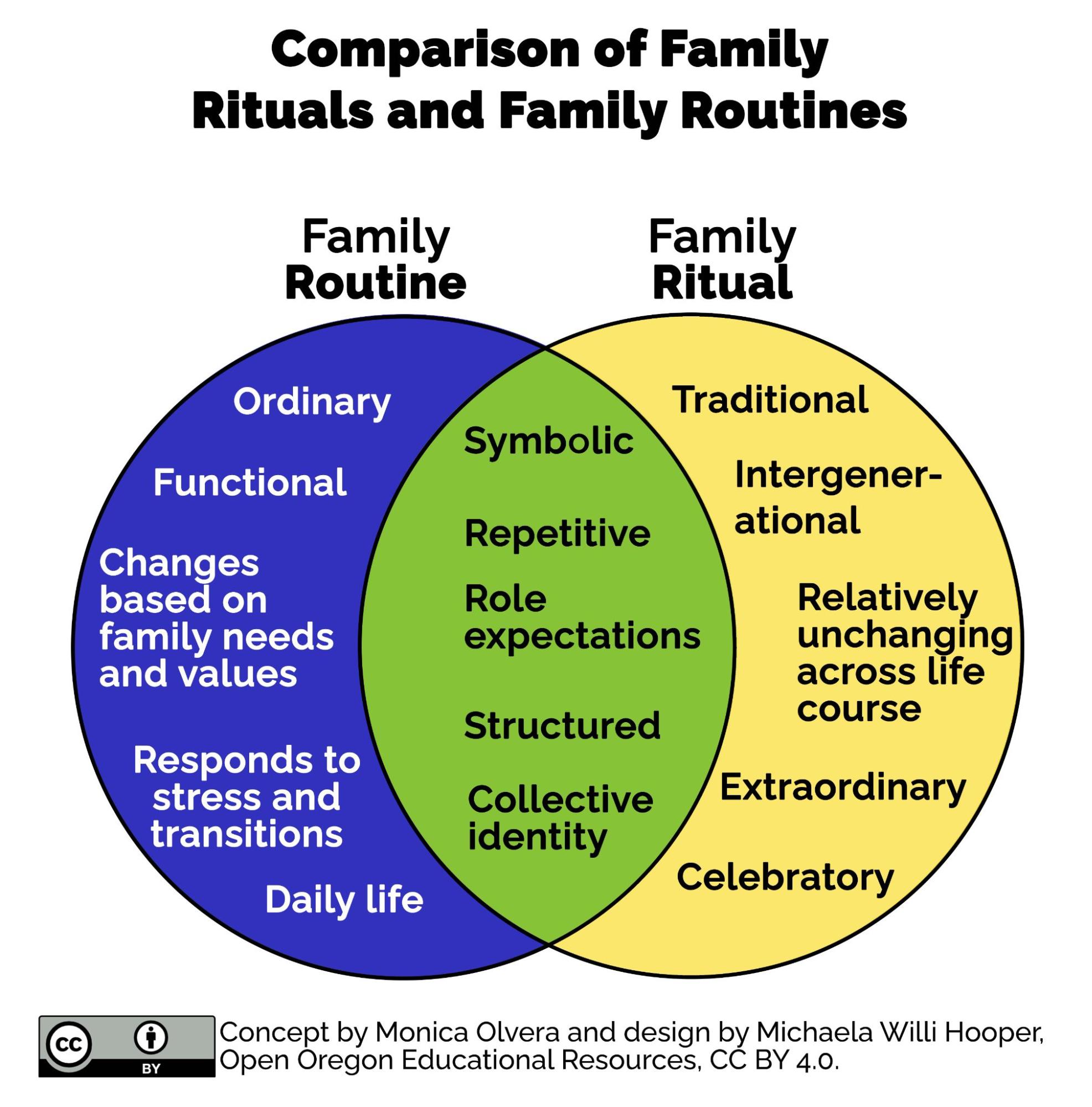

What are the differences between routines and rituals? When families attribute significance and meaning to routines, especially those that promote family cohesion and family identity, routines can become rituals. As previously discussed, family routines are the predictable, repeated, consistent patterns that characterize daily home life. In contrast, family rituals are “compelling…behaviors with symbolic meanings that can be clearly described and serve to organize and affirm central family ideas” (Steinglass et al., 1987, as cited in Denham, 2003).

Figure 5.2 provides a comparison of family rituals and family routines. Family routines and rituals overlap in many ways with respect to their meanings, associations, ways they are initiated, and meaning. Routines tend to be tied to everyday life and may not hold special meaning, whereas rituals tend to be carried out in association with extraordinary events and often have symbolic significance.

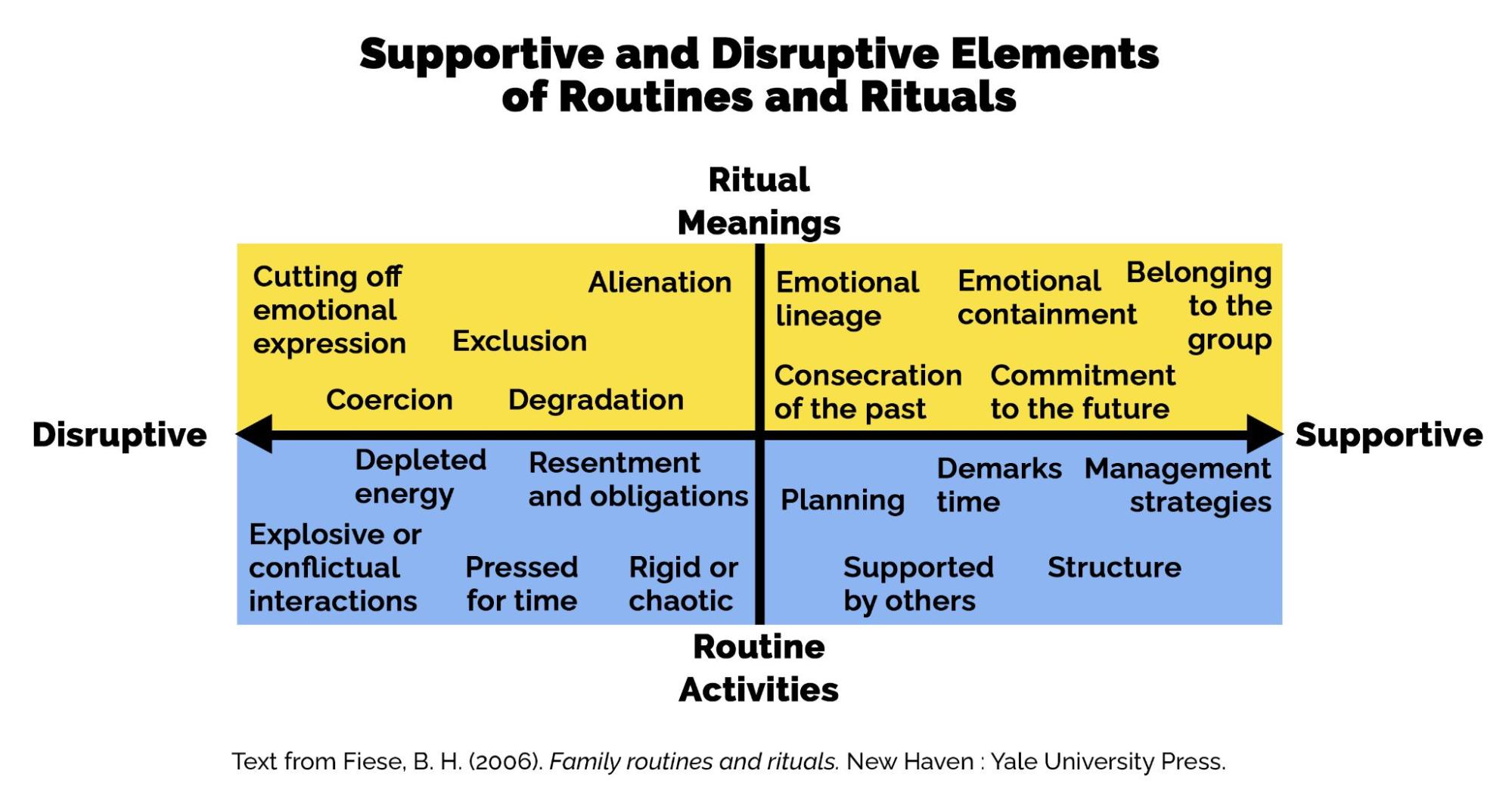

Routines and rituals build a sense of belonging, family cohesion, and family identity. While family routines can be supportive for families, they can be disruptive if they are too rigid or chaotic, require too much time or energy, lead to conflicts among family members, or contribute to family members resenting each other (Fiese, 2007). Figure 5.3 provides a summary of the supportive and disruptive elements of family routines and rituals.

Family routines can become rituals when symbolic meaning is attached to the activity. Ritual meanings can become disruptive to families, however, if family members feel alienated or excluded, if they are cut off from emotional expression during the ritual, or if they feel coerced at any point during the ritual (Fiese, 2007). A disruption of family rituals can erode group cohesion for the family. A regular disruption of routines can be harmful because it contributes to an accumulation of stress beyond what the family can handle (Harrist et al., 2019).

Rituals Related to Life Transitions

Many cultures and societies practice rites of passage. A rite of passage can be a ritual or celebration that marks the passage when a person leaves one status, role, set of conditions, or group to enter another. Rituals and celebrations that mark a rite of passage are typically performed within a community setting and are community-created and community-directed. The rite can be a public affirmation of shared values and beliefs, such as a marriage ceremony, or it can promote community identity and cohesion, such as a powwow. Rites of passage can guide a person’s transition into a new role, status, or phase, as seen in a commencement ceremony to mark a person’s graduation from high school. Anthropological records show that humans have practiced rites of passage for thousands of years, in many different forms, and across all cultures.

Now we will describe four life transitions that are common for human experiences in the United States. The examples described below represent a minuscule fraction of the ways in which individuals, families, and communities practice rites of passage.

Birth/Family Formation

Birth is the beginning of a new life, and, therefore, a unique life event and rituals can be a key part of marking and celebrating such an event (Wojtkowiak, 2020). Similar to other life passages (such as adulthood, marriage, or death), considering birth as a social transition means that the pre-status or social order is temporally in a space of transition and a status of being in between two spaces or statuses. Parents-to-be are preparing mentally, materially, or even spiritually for the coming of their child and the transition into becoming parents. Family members and friends are searching for new roles in the life of this new human being. Experiencing the birth of a baby can bring feelings of happiness and joy, as well as ambiguity and uncertainty. The coming of a new member of society has been traditionally marked by rituals. Birth is, therefore, understood as the first rite of passage in a human life (Van Gennep, 1960).

Rituals and ceremonies performed around the time of birth serve as celebrations to mark the occasion. Rituals can also help parents transition into new roles, as well as establish relationships of care, support, and responsibility within a community of friends and family. In this section, we will look at examples of “blessingway” ceremonies, and secular naming ceremonies.

“Blessingway” ceremonies, or “mother’s blessing,” is inspired by the traditional Navajo blessingway ceremony (Biddle, 1996). Traditional blessingway ceremonies consist of singing, chanting, and sharing stories to wish beauty, good, and harmony to the mother-to-be. The songs and stories are shared during pregnancy and childbirth. The singer, who is a traditional medicine man, performs the songs. The songs and stories are important for the mother-to-be and shape her view of childbirth and family life. Through the chants, the woman is spiritually connected to her ancestors and the past and future (Biddle, 1996). A modern mother’s blessing is described as a “celebration of a woman’s transition into motherhood that’s rooted in Navajo culture. It is a spiritual gathering of the woman’s closest friends and family who come to nurture the mama-to-be with wise words, positivity, art, and pampering.” (Your guide to throwing a virtual blessingway, baby shower & gender reveal, 2020). During a mother’s blessing, the mother is blessed by other significant women before the baby is born. Most of the time, the other participants are her mother and mother-in-law, sisters, aunts, and friends. However, variations are possible, and sometimes men are also present.

Naming or welcoming ceremonies for babies, inspired by traditional baptism (which typically involves water sprinkling or immersion, and religion), is a reinvented way of welcoming the baby into one’s community. It is practiced as an alternative to religious baptism. The motivation for a baby-naming ceremony is for parents or caregivers to have a ceremony that brings together friends and family to celebrate one of life’s key milestones. Naming ceremonies are ideal for families who want to mark the occasion in a way that isn’t religious. A naming ceremony is personalized and uniquely created for each family and can last between 20 to 60 minutes. Parents and other significant others can, for instance, state their hopes and wishes for the baby. “Wishes for a Child” by Joanna Miller is an example of a poem for a naming ceremony, and it appears here with other poems. Music and readings can also be part of the ceremony. Some physical symbols might be given to the baby, such as a token for guidance or something that the child can open or read later in their life. “Guideparents” might be presented to the community, and they can express their wishes to the baby. As this ritual is individually crafted for each family, the location, length, content, and other ritual elements are chosen for the occasion.

Entry into Adulthood

Coming-of-age rituals are the ceremonies or traditions that mark the leaving behind of childhood or adolescence and the entry into adulthood, maturity, or increased level of responsibility and duties. Many times a coming-of-age ritual is rooted in religious tradition, such as Bar and Bat Mitzvahs in Judaism or the Sacrament of Confirmation in Catholicism. Secular coming-of-age practices can include getting one’s driver’s license, débutante balls, high school senior prom, and graduation, or a quinceanera, as pictured in figure 5.4.

In Focus: La Quinceañera: A Rite of Passage among Latina Adolescents

“Hurry, mamá!” Laura begged her mom. “¡Ayúdame a quitar la falda! ¡Ya va a empezar el baile sorpresa and I’m not even wearing my folklórico dress yet!” which translates into English as “Help me take off this skirt! The surprise dance is about to start!” Laura was hurriedly trying to unlace the glittery, bedazzled gown to put on her Jalisco dress to dance to “El Son de la Negra” with her corte de chambelanes y damas, her court of young men and women who would accompany her. Amy, Laura’s mom, clumsily helped Laura unlace the bodice of the dress, then helped Laura step into her Jalisco dress, careful not to get any of Laura’s curls stuck in the zipper. The scene felt like a fiasco because the guests were waiting to see the baile sorpresa. It was Laura’s quinceañera, the elaborate party and celebration of Laura turning 15 a few months ago, a ritual that many other Latina girls her age had gone through or were already planning for their birthdays. Laura had practiced the dance for months with her court members, and it was almost the moment to debut the choreographed and stylized dance for the party guests, a mixture of Laura’s extended family members, friends, Amy’s coworkers, and even guests that had flown to Chicago for the big event.

Finally, Amy finished helping Laura secure her skirt and clasp her shoes, and with a whoosh, the pair of them rushed out to the reception hall. Laura took her place on the dance floor by the chambelan de honor, the male escort of honor, and turned her head to catch the DJ’s eye. The DJ saw Laura in position to begin the dance with the court, queued up the music, and belted out a command to the guests, “Damas y caballeros, un fuerte el aplauso para Laura y los chambelanes. pon la música!” which translates in English to “Ladies and gentlemen, give a big round of applause for Laura and her court! DJ, play the music!”

As the music started and Laura’s court of friends and cousins began to dance, Amy released a huge sigh of relief. This momentous occasion, which the family had saved for over the years and which had taken almost a year of planning, was finally coming to fruition. Laura and her parents, family, friends, and community were celebrating this important coming-of-age ritual, cementing the family’s sense of cohesion and identity and Laura’s symbolic rite of passage into a performance of womanhood.

The quinceañera, a rite of passage that marks the 15th birthday of Latina girls, is practiced by Latinos of various backgrounds and nationalities throughout the United States and Latin America. (The term “quinceañera” refers both to the ritual and to the girl celebrating her 15th birthday.) While it has many variations, quinceañeras were typically practiced by elite families in Mexico. The tradition has been transported to and transformed within the United States. The previous vignette describes the quinceañera, Laura, preparing for the surprise dance portion of the quinceañera, a ritual within a ritual.

From a parent’s point of view, watching a youth grow into maturity and take on the roles, responsibilities, and risks of adulthood can be both exciting and frightening, as the parent struggles with letting their child have more autonomy while also fearing for their child’s well-being and safety. In this TED Talk, Marc Bamuthi Joseph shares a Black father’s tender and wrenching internal reflection on the pride and terror of seeing his son enter adulthood.

Marriage/Union Formation

Chapter 3 describes different types of unions, partnerships, and relationships, with a specific focus on marriage, that have a range of legal, religious, or community acceptance. In this section, we present a few examples of marriage and union formation rituals practiced by families in the United States. Union formations have been practiced by cultures and societies around the world for millennia. The video “The History of Marriage” provides a succinct introduction to marriage practices around the world, such as polygamy, a marriage form permitting more than one spouse at the same time.

“Jumping the broom” is a marriage tradition that some African American couples practice (figure 5.6). The tradition was mainly practiced by enslaved couples, who did not have access to the legal right of marriage due to the rampant racial discrimination that existed in the institution of chattel slavery. A couple would publicly proclaim their commitment and devotion to each other, sometimes with a priest/minister or the enslaver officiating the ceremony.

Variations of the practice could involve the couple jumping over a broom placed sideways or jumping over two brooms. The broom could be held up or placed on the ground, and the couple could jump or step over the broom at the same time or one person at a time (Dundes, 1996).

The ritual was typically regarded as a binding agreement for the couple, potentially to the extent that it was legally recognized.

While the origin of the practice is unclear, some scholars suggest brooms were symbolic in wedding rituals in Africa and thus were incorporated into wedding traditions of enslaved people in the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries (Dundes, 1996). Other researchers suggest the practice originated in the British Isles (Parry, 2020).

In contemporary weddings, couples may choose to incorporate jumping the broom into their wedding ceremony. This practice could typically occur toward the end of a wedding ceremony, when the couple has exchanged their vows in front of a room filled with friends, family, and loved ones, as the last step in culminating the wedding ceremony. A broom would be placed on the ground in front of the couple, facing the guests, and a speaker would describe the origins of the practice and what the practice symbolizes for the new couple.

For example, in this video excerpt of a couple’s ceremony, we can see a couple standing in front of the broom while the officiate speaks to the guests:

We now end this ceremony with the African tradition of jumping the broom. Slaves in this country were not permitted to marry, so they jumped the broom as a way to [demonstrate] unity. Today it represents great joy and at the same time serves as a reminder of the past and the pain of slavery. As our bride and groom jump the broom, they physically and spiritually cross the threshold of the path of matrimony…in making their home together. It represents the sweeping away of the old and welcoming the new. The sweeping away of negative energy, making the way for all things good to come into their lives. It is also a call of support for the marriage from the entire community of family and friends. The bride and groom will now begin their new lives together with a clean sweep.

Then, the speaker asks the guests to stand and count to three, upon which the couple hops over the broom together while the guests erupt into cheers and applause.

Death and Bereavement

Death and bereavement, or mourning the passing of a loved one, are recognized in a variety of ways, depending on the family’s own traditions and culture. The passing of a loved one can be a time of great sadness but also of joy in celebrating a person’s life and legacy. Rituals can provide opportunities for friends and family to mourn the passing of a loved one and to gather and comfort one another. In this section, we will look at the example of bereavement practices among Asian Indian American Hindus (AIAHs) residing in the southern region of the United States.

Beliefs about the end of life and the meaning of death as a transition to another life can help people feel less anxiety about death (Chopra, 2006). Ethnicity can provide a cultural system to make sense of the world, including suffering and loss (Gupta, 2011). AIAHs interviewed by Dr. Rashmi Gupta (2011) accessed their cultural and religious beliefs to help them make sense of death and loss, as well as provide comfort in mourning practices. In focus groups Gupta conducted with AIAHs, individuals discussed their traditional beliefs and practices and described how death and bereavement are approached in India as opposed to the United States. AIAHs strive to adhere to their religious and cultural practices as much as possible within the resources available to them in the United States. Gupta (2011) noted that the death rituals and customs followed include “delivering a eulogy, embalming at Hindu funerals, a 1- to 2-day mourning period instead of 13 days, donation of the body to science instead of cremation, and allowing the funeral home to perform the cleansing of the deceased instead of the son” (p. 257).

Despite the majority of Hindus in India believing that life-prolonging means interfere with the cycle of life and death, in the United States, some Hindus have utilized artificial means to prolong life, such as a respirator. Some Hindus in the United States follow pre- and post-death rituals, whereas others do not. In India, widows are expected to wear white saris and refrain from wearing makeup or jewelry for the remainder of their lives as a sign of mourning. However, in the United States and India, this custom is changing, with widows in the United States wearing colors that do not prevent them from blending into the workforce (Gupta, 2011).

The variation in adherence to practices may vary according to the degree of one’s acculturation, place of birth, religious orientation, and availability of priests and temples. The AIAH seniors Gupta interviewed stated that they were not afraid of death, but they were concerned about getting very sick and becoming a burden for their adult children. They were not too concerned, however, about their adult children’s ability to carry out rituals and customs that the seniors had performed for their own parents in India, as the adult children would follow the guidance and recommendations of the priest at their respective places or religious gatherings (Gupta, 2011).

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for Traditions and Rituals

Open Content, Original

“Traditions and Rituals” and all subsections except those noted below by Monica Olvera. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.2. “Comparison of Family Rituals and Family Routines” by Monica Olvera and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.4. “Quinceañera. Santa Fe” by Christopher Michel. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 5.5. “Quinceañera” by Thank You. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 5.6. “Jumping the Broom at a Los Angeles Wedding in September 2011” by Hipstamatic Shots from Lisa & Lorna. License: CC BY-SA 2.0.

Birth/Family Formation is adapted from “Ritualizing Pregnancy and Childbirth in Secular Societies: Exploring Embodied Spirituality at the Start of Life” by J. Wojtkowiak. Adaptations include excerpting sentences, shortening for brevity and reading level. License: CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 5.3. “Supportive and Disruptive Elements of Routines and Rituals” based on text from Family Routines and Rituals by Barbara Fiese. License: Fair Use.

References

Alvarez, J. 2007. Once upon a Quinceañera: Coming of Age in the USA. New York NY: Viking.

Biddle, Jeanette M. 1996. The Blessingway: A Woman’s Birth Ritual. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA.

Cantú, N. 1999. La Quinceañera: Towards an ethnographic analysis of a life cycle ritual. Southern Folklore 56(1): 73–101.

Chopra, D. (2006). Life after death: The burden of proof. New York, NY: Harmony Books.

DAVALOS. (1996). “La Quinceañera”: Making Gender and Ethnic Identities. Frontiers (Boulder), 16(2/3), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346805

Denham, S.A.(1995).Family routines: A Construct for considering family health. Holistic Nursing Practice, 9(4), 1123. Retrievedfrom http://journals.lww.com/hnpjournal

Dundes, A. (1996). “Jumping the Broom”: On the Origin and Meaning of an African American Wedding Custom. The Journal of American Folklore, 109 (433), 324–329. https://doi.org/10.2307/541535

Erevia, A. (1996). Quince Años: Celebrating a Tradition: A Handbook for Parish Teams. Missionary Catechists of Divine Providence. pp. 1–42.

Fiese. (2006). Family Routines and Rituals: New Haven: Yale University Press (p.25)

Fiese. (2007). Family Routines and Rituals: Opportunities for Participation in Family Health. OTJR (Thorofare, N.J.), 27(1_suppl), 41S–49S. https://doi.org/10.1177/15394492070270S106

González-Martin, R. V. (2021). Buying the Dream: Relating “Traditional” Dress to Consumer Practices in US Quinceañeras. In Mexicana Fashions (pp. 137-157). University of Texas Press.

Gupta. (2011). Death Beliefs and Practices from an Asian Indian American Hindu Perspective. Death Studies, 35(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2010.518420

Harrist, A. W., Henry, C. S., Liu, C., & Morris, A. S. (2019). Family resilience: The power of rituals and routines in family adaptive systems. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan (pp. 223–239). American Psychological Association.

Horowitz. (1993). The Power of Ritual in a Chicano Community: A Young Woman’s Status and Expanding Family Ties. Marriage & Family Review, 19(3-4), 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v19n03_04

Hull, K. (2006). Same-Sex Marriage: The Cultural Politics of Love and Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511616266

Parry. (2020). Jumping the broom : the surprising multicultural origins of a black wedding ritual. The University of North Carolina Press.

Steinglass, P., Bennett, L., Wolin, S., & Reiss, D. (1987). The alcoholic family. New York: Basic Books.

Van Gennep, Arnold (1977) Vizedom, Monika B (Translator); Caffee, Gabrielle L (Translator) (1977) [1960]. The Rites Of Passage. Routledge Library Editions Anthropology And Ethnography (Paperback Reprint Ed.). Hove, East Sussex, Uk: Psychology Press. Isbn 0-7100-8744-6.

Wojtkowiak, J. (2020). Ritualizing Pregnancy and Childbirth in Secular Societies: Exploring Embodied Spirituality at the Start of Life. Religions, 11(9), 458. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/rel11090458. CC BY 4.0.

Your guide to throwing a virtual blessingway, baby shower & gender reveal. (2020, April 29). MiLOWE. https://www.milowekids.com/the-mag/your-guide-to-throwing-a-virtual-blessingway-baby-shower-or-gender-reveal

can include the emotional significance of an action or way of being; the intention or reason for doing something; something that we create and feel; closely linked to motivation.

a ritual or celebration that marks the passage when a person leaves one status, role, set of conditions, or group to enter another.

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.

a socially constructed expression of a person’s sexual identity which influences the status, roles, and norms for their behavior.

the developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult.

an intimate relationship, in which two or more people commit to some kind of union, including marriage.

the unequal treatment of an individual or group on the basis of their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex).

the geographical location where a person was born and spent (at least) their early years in.

the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national, ancestral, or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another.

the process of adapting to a new culture.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes and internal/external reproductive organs.