9.2 What Children and Families Need to Be Safe

Alexandra Olsen

Safety and stability are fundamental aspects of both Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory and First Nations perspectives on needs, which we discussed in Chapter 3. In Maslow’s hierarchy, individuals need physical safety to achieve self-actualization. Similarly, the idea of safety is inherent to First Nations ideas about meeting the community’s needs, where the safety of a community is essential to cultural perpetuity.

Maslow’s theory and First Nations perspectives show us that safety can be co-created in communities and experienced individually. Safety can be a public policy goal, such as the passage of a law increasing funding for afterschool programs. Organizations, such as services provided to people leaving abusive relationships, also create safety. In relationships, safety grows from the intense love, trust, and connection between child and parent. Finally, individuals can create safety and develop through positive childhood experiences and by learning social and emotional skills.

There are different kinds of safety that individuals, families, and communities experience:

- Physical, which includes access to resources like food and water. It also includes freedom from violence and freedom from anyone touching your body without consent.

- Psychological, which is freedom from excessive worry of physical or emotional harm. This does not mean that bad things never happen. Instead, when people have psychological safety, they feel they can openly communicate with others and find solutions to problems.

- Spiritual, which is when they feel comfortable being themselves because others acknowledge, understand, and engage respectfully with them. Spiritual safety emerges in contexts where there is mutual understanding and support.

- Communal, which is when a person has a sense of belonging and attachment to their family, broader social groups, and families. It also means that people within these social groups are free to express their culture, supported, and able to thrive in perpetuity.

This chapter will explore these kinds of safety and learn what children and families need to be safe. We will look at both macro-level and micro-level aspects. We’ll also discuss how freedom from abuse and violence is integral to creating safety but one that many families struggle to obtain. Finally, we’ll examine families’ barriers to achieving a sense of safety and how policies and communities have progressed on these issues.

Macro-Level and Micro-Level Aspects of Safety

Many factors contribute to families’ and individuals’ ability to be safe. These include macro-level factors: policies, institutions, communities, and cultures that promote safety and security. Other factors work at the micro-level to create safety and security: close relationships, social service interventions, and individuals’ social and emotional skills.

Before we look more in-depth at the macro- and micro-level factors contributing to safety, we will briefly discuss why safety is so important, especially during childhood and adolescence. The safer and more stable families and communities are, the better they will be able to provide their children with protective childhood experiences. These experiences improve children’s resilience during adversity and, in some cases, avoid ACEs.

Protective and Compensatory Childhood Experiences

Individuals need safety throughout their life course, particularly during childhood, because of its role in cognitive and emotional development (Morris et al., 2021). Families play a significant role in providing children with experiences that will help them grow into happy, stable, and successful adults. When families and communities have a sense of safety and stability, they can provide children with the security they need to develop into productive adults.

Public health scholars have identified ten protective and compensatory childhood experiences (PACEs) that help children develop resilience. These experiences can promote resilience even if children have some adverse or traumatic childhood experiences (Morris et al., 2021). PACEs are fulfilled by:

- A caregiver who loves them unconditionally.

- A best friend who they can trust and have fun with.

- An adult who is not their parent that they can trust and turn to for advice.

- Regular opportunities to help others through volunteering or participation in other community projects.

- Physical activities and/or sports.

- Social groups, such as places of worship, scout groups, community groups.

- Hobbies, such as arts and crafts, reading, debate team, or playing a musical instrument.

- A school with the resources and academic experiences that they need to learn.

- A home that is clean, safe, and where there is enough to eat.

- A home with routines and fair, clear, and consistently enforced rules.

The ability to provide children with these experiences is directly related to macro- and micro-level factors associated with safety. These experiences can only exist at the macro-level if families have access to resources—such as food, money, access to quality schools, and time to engage in the community. At the micro-level, these experiences are born out of healthy relationships and a sense of community, as pictured in figure 9.1—children knowing they have people who care about them. If we want children to grow into resilient adults, then we need families and communities to have the support they need. Families with support can provide children with needed resources and build strong relationships.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

When families don’t have the things they need to be safe, children are more likely to be exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which are traumas that occur in an individual’s life before they turn 18, including neglect, abuse, and household difficulties. The greater the number of ACEs that an individual has experienced, the greater the likelihood of poor social, emotional, and health outcomes in the short and long term. Specifically, researchers have identified 10 ACEs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021):

- Emotional abuse

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Witnessing violence against mother/stepmother

- Substance abuse in the household

- Mental illness in household

- Parental separation or divorce

- Incarcerated household member

- Emotional neglect

- Physical neglect

Hudson Center for Health Equity and Quality has developed an online calculator for ACEs where you can calculate your ACE score. This online tool is based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Kaiser ACEs Study but is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment. You can access the online calculator here.

ACEs impact children in the short and long term. In the short term, children may internalize or externalize their emotions related to the trauma that they have experienced. Children may respond to these experiences by externalizing their emotions, a psychological defense mechanism in which they direct uncomfortable feelings at others or “act out.” They may engage in inappropriate or disruptive behavior or become diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or conduct disorders. In contrast, children may respond to these issues by internalizing their emotions, a similar defense mechanism that involves holding in or hiding their feelings. Children who internalize may experience anxiety and/or depression. In both cases, children’s neurodevelopment is disrupted, which leads to a greater likelihood of long-term impacts from these experiences (McLaughlin et al., 2015).

To focus on the long-term effects of trauma as well as the ways that communities can address safety and trauma, you may watch a video featuring the former Surgeon General of California and pediatrician Dr. Nadine Burke Harris in the“Going Deeper” section. Childhood Trauma Over the Lifetime offers a discussion and analysis of ACEs impact on health in the long term, but also ways that communities can address these issues to support families.

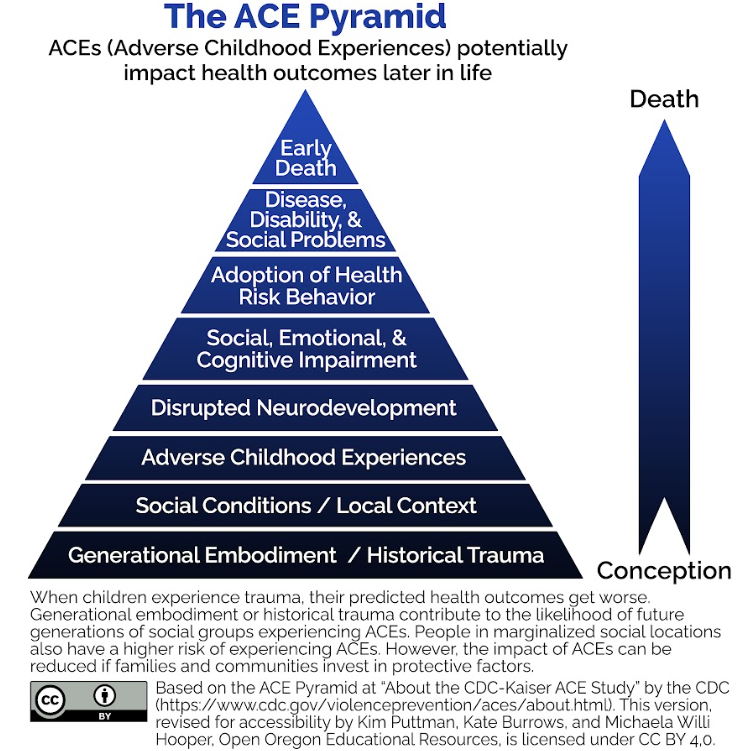

In the long term, ACEs can impact health across the lifetime. Figure 9.2 shows the pathway from ACEs to poor health outcomes and well-being over the life course.

Macro- and micro-level factors that promote safety directly connect to ACEs. ACEs arise from a combination of social conditions and individual interactions. For instance, when we look at the bottom of the ACE pyramid in figure 9.2, we can see how issues such as historical trauma or other social/community conditions can lead to ACEs. These are macro-factors that indicate a lack of safety for families.

At the same time, the extent to which ACEs impact a child depends on their exposure to PACEs. Many of these protective factors function at the micro-level—quality relationships and a sense of support—and connect back to the broader needs for families to access resources. Not every child exposed to trauma will have significant and severe long-term negative consequences. However, the greater the number of protective factors children have, the lower the likelihood that ACEs will have severe long-term outcomes.

Public health initiatives to address the impact of ACEs and trauma in children are crucial. Addressing this impact requires the government and organizations to put resources towards helping families and educating families on the effects of ACEs. Additionally, families must be open to learning skills to heal from trauma and improve their relationships. An example of what this can look like in practice can be found in the box below, highlighting the group Creating Community Resilience in Douglas County, Oregon. Moving forward, we’ll look at how access to resources and families’ community and individual relationships influence their sense of safety.

In Focus: Creating Community Resilience

In Douglas County, Oregon, Creating Community Resilience aims to inform the community about the impact of ACEs and integrate trauma-informed practices into local schools, county agencies, and nonprofits.

One of the strengths of this group is that they bring together a wide range of community groups to accomplish these goals. The involved organizations include local school districts, the juvenile department, health care providers, social service agencies, the Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua Tribe of Indians, and Umpqua Community College. All these agencies play a role in educating the public, implementing trauma-informed practices, and working with other community groups to spread the impact of this work. Regularly, members of this group will give ACE Interface trainings to local groups. These trainings explain the Kaiser ACE study, discuss protective factors against ACEs, and provide information about how community members can address these issues.

They also hold “Lunch and Learn” monthly events for community members. At these lunches, community members can learn more about trauma-related issues and the work being done in Douglas County to address trauma. Through all of this work, Creating Community Resilience is taking active steps to mitigate the impact of trauma in Douglas County by both strengthening the skills of local professionals to address these issues in a wide range of contexts and educating the general public.

Comprehension Self Check

Licenses and Attributions for What Children and Families Need to be Safe

Open Content, Original

“What Children and Families Need to Be Safe” by Alexandra Olsen. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.2. “The ACE Pyramid” by Kim Puttman, Kate Burrows, and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Creating Community Resilience” by Alexandra Olsen. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.1. Photograph by Joel Muniz on Unsplash. License:Unsplash License.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, April 6). About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html.

McLaughlin, K.A., Sheridan, M.A., and Lambert, H.K. (2015). Childhood Adversity and Neural Development: Deprivation and Threat as Distinct Dimensions of Early Experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578-591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012

Morris, A.S., Hays-Grudo, J., Zapata, M.I., Treat, A., and Kerr., K.L. (2021). Adverse and Protective Childhood Experiences and Parenting Attitudes: the Role of Cumulative Protection in Understanding Resilience. Adversity and Resilience Science, 2, 181-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-021-00036-8

a structural framework, explanation, or tool that has been tested and evaluated over time.

the shared meanings and shared experiences passed down over time by individuals in a group, such as beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society.

the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

failure to meet a child's basic needs.

nonphysical maltreatment through verbal language.

any act, completed or attempted, that physically hurts or injures someone.

maltreatment, violation, and exploitation where a perpetrator forces, coerces, or threatens someone into sexual contact for sexual gratification and/or financial benefit.

a wide range of mental health disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior.

ensuring that people have what they need in order to have a healthy, successful life that is equal to others. Different from equality in that some may receive more help than others in order to be at the same level of success.

cumulative emotional and psychological wounding across generations, including the lifespan, which emanates from massive group trauma.